September 22, 2023

Dear Members of the Board of Governors, FDIC Chairman, and Acting Comptroller of the Currency:

On August 7, Better Markets (BM) sent a letter to the federal bank agencies asserting that the proposed CRA rule “will not work and that redlining will continue.” The BM letter dismisses an interagency proposal that would likely increase reinvestment.

While not perfect, the proposed rule amounts to the most comprehensive set of changes to CRA since the last regulatory re-write in 1995. The importance of finalizing and implementing the proposed rule cannot be over-emphasized. In the wake of the pandemic, communities need more loans, investments, and services to gain lost ground and to resume their growth and revitalization. This is the best rule we have seen in a generation; it represents a massive effort by the agencies, community groups, and other stakeholders that provided input to the agencies. It must be finalized, not abandoned.

While we agree with BM that the retail lending test is imperfect, the solution is to seek improvements, not to dismiss the proposed test which we believe has a solid foundation. Further, the BM letter focusses on the retail lending test and does not address or account for the proposed rule’s other important advances, including proposed reforms to assessment areas (geographical areas on CRA exams) to take into account branchless lending, data enhancements to better capture deposit services and community development financing, and test re-design to more accurately measure reinvestment activities.

The major points in this letter include:

- The agencies’ proposed lending test relies on two benchmarks – a community and a market benchmark. The proposed benchmarks have threshold levels expressed in percentages that correspond to ratings on the lending test. These threshold levels can readily be adjusted to be more stringent if early CRA exam results after implementation of the proposed rule indicate that inflated ratings remain prevalent.

- BM’s proposals to counter ratings inflation are not effective and remove informative performance measures. After BM simulates its recommendation to remove the community benchmark and the 60% pass rule, the percent of its failed ratings is about the same as the agencies’. It is unclear what is gained by BM’s proposal.

- BM’s proposal to remove the community benchmark would result in CRA exams with less local context. The community benchmark assesses the extent to which banks are serving low- and moderate-income borrowers in local communities. Without this benchmark, the public would have considerably less information regarding the extent to which banks are responding to demographic trends and the needs of low- and moderate-income households.

- BM asserts that the agencies’ proposed 60% pass rule is arbitrary. In contrast, NCRC believes that a requirement for banks to pass their CRA exams in at least 60% of their local geographic markets is essential to making sure they meet the needs of the communities in which they conduct business. NCRC has asked the agencies to raise this threshold to 70% and to also apply it separately to smaller metropolitan areas and rural areas in addition to larger metropolitan areas.

- BM proposed a measure of underserved areas as those with low levels of loans compared to low- and moderate-income households. BM would weigh ratings more in geographical areas with lower ratios of loans to households as a means of encouraging banks to avoid neglecting credit needs in underserved areas. However, a low level of lending per capita could result due to expensive housing or lower levels of creditworthiness in some areas. Hence, the heavier weighting could be an inappropriate solution in several cases.

- Instead, NCRC prefers the 60% pass rule. In terms of underserved populations, NCRC has proposed a performance measure on the lending test for underserved census tracts which would address BM’s concerns and would also direct banks to addressing needs in communities of color that are disproportionately underserved.

- BM is incorrect that the agencies’ proposal would allow redlining to continue. They suggest that the loan-to-deposit ratio would not be effective in detecting redlining. However, this ratio is not designed to identify redlining. Instead, the agencies engage in data analysis and spatial mapping to identify banks that are redlining and that make few loans in communities of color.

- According to BM, a central failing of CRA is a falling homeownership rate for low- and moderate-income households. However, BM does not consider broader economic trends such as the financial crisis or the CRA research literature which concludes that CRA has had positive impacts on homeownership, branching, and small business lending in low- and moderate-income communities.

Proposed Retail Lending Test – a sound test that could be tweaked

A review of the proposed retail lending test will facilitate the exploration of the BM critique of this test, particularly regarding home lending. The proposed test would have two benchmarks against which a bank’s lending would be measured. The first is a community benchmark or the percentage of households or census tracts that are low-income and moderate-income. The second is the market benchmark or the percentage of all lenders’ loans in the geographical area that are made to low- or moderate-income borrowers or in low or moderate-income census tracts.

As the agencies explain, the community benchmark captures a locality’s demographics, specifically the percentage of low- and moderate-income households and tracts. CRA exams have been comparing a bank’s lending to local demographics for decades. BM criticizes the community benchmark as devoid of meaning since it does not capture demand. The agencies understand this and do not expect the percentage of a bank’s loans to equal the percentage of either low-income or moderate-income households or census tracts in a geographical area. Instead, it is a measure of the extent to which a bank is serving a subgroup in the population. The agencies used data from previous CRA exams over several years to calculate thresholds that represent fractions of low- or moderate-income households or tracts that a bank would need to meet in order to achieve a specified rating on the retail lending test. Likewise, the agencies choose thresholds for the market benchmark.

Proposed multipliers: Select the lesser of two values[1]

| Threshold | Market multiplier and benchmark | or | Community multiplier and benchmark |

| Needs to Improve | 33% of mkt. bench. | or | 33% of com. bench. |

| Low Satisfactory | 80% of mkt. bench. | or | 65% or com. bench. |

| High Satisfactory | 110% of mkt. bench. | or | 90% of com. bench. |

| Outstanding | 125% of mkt. bench. | or | 100% of com. bench. |

The overall objective is to create a ratings system that avoids ratings inflation and in which ratings meaningfully reflect distinctions in performance. The current system, for example, awards about 90% of banks with the overall Satisfactory rating. Regardless of whether the ratings distribution is overall or for the component tests, it is not meaningful to have 90% of banks in any one ratings category. The tables in the proposal suggest that banks would be distributed meaningfully across the categories for the proposed Retail Lending Test and that banks are not bunched in an exaggerated manner in any of the five subtest categories.

A secondary objective is creating a ratings system that makes reasonable judgments regarding the percentage of a bank’s loans to a group of borrowers or tracts in relation to peers and demographics. NCRC has observed over the years that banks generally have a more difficult time issuing a percentage of loans that is similar to the percentage of low- and moderate-income borrowers or tracts than a percentage of loans similar to that of their peers in a geographical area. A subset of modest income populations is not ready for homeownership, which accounts for part of the difficulty of lending in proportion to these populations. Hence, the multipliers for the community benchmark should be lower than those for the market benchmark as the agencies proposed (and shown in the table above). However, the agencies’ multipliers for the community benchmark get progressively more challenging with each ascent up the ratings categories. They are set at 90% for High Satisfactory and 100% for Outstanding, which appropriately signals to banks that if they want the higher ratings they should strive for lending in proportion to low- and moderate-income borrowers or census tracts.

The market benchmark is the percentage of loans made by all lenders, including non-banks, in the geographical area. It is generally easier for banks to meet or exceed the market benchmark. Hence, the agencies appropriately established higher multipliers for the market benchmark. In order to achieve Low Satisfactory, the bank’s percentage of loans to a subgroup of borrowers or tracts needs to be at least 80% of the market benchmark, which acknowledges that a bank is performing below average but not too far below average to achieve a passing rating. The High Satisfactory multiplier of 110% implies that a bank needs to be moderately above peer levels to achieve this rating.

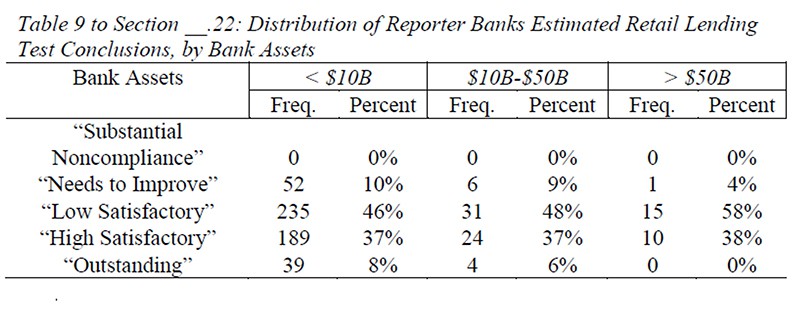

In order to achieve Outstanding, the bank needs to be at 125% of peer levels, which is appropriate due to NCRC’s observations over the years that banks cluster around the market benchmark. Therefore, in order to distinguish performance as Outstanding, a bank should be significantly better than a cluster of its peers. Moreover, Table 9 (reproduced below) in the agencies’ proposal showed that banks would achieve Outstanding ratings at modestly less rates than currently (banks with assets at less than $10 billion would be Outstanding at 8% of the time and those with assets between $10 and $50 billion would be Outstanding at 6% of the time).[2] This multiplier raises the bar but does so in a manner that is achievable and realistic.

In our comments, NCRC suggested that the agencies should consider a weighted average approach instead of choosing the lower of the community or market benchmarks. Selecting the lower benchmark could result in lower thresholds that inflate ratings. For example, in assessment areas in which the market benchmark is considerably lower than the community benchmark, all lenders could be under-performing in making loans to low- and moderate-income borrowers or communities. In these situations, using the lower market benchmark could excuse poor performance.

The agencies contemplated a weighted average of between 70% to 90% for the market benchmark.[3] In cases in which the market benchmark is considerably lower than the community benchmark and a lack of performance context factors (such as a local recession) that could account partly for this outcome, the weight of the market benchmark should be lower, perhaps at 50%. The agencies could choose weights depending on the discrepancy between the two benchmarks and whether performance context factors explain part of the discrepancy.

Conversely if the community benchmark is lower than the market benchmark, a weighted average approach would more successfully motivate banks to improve performance rather than using the lower community benchmark. Again, weights applied to both benchmarks would depend on the discrepancy between the benchmarks and performance context factors.

The agencies should select weights, not examiners, in order to promote consistency across exams and prevent CRA ratings inflation. The agencies should conduct data analysis, consider performance context factors across metropolitan areas and rural counties, and consider discrepancies between the benchmarks in order to create a range of weights that reflect differences in market and demographic conditions.

The agencies’ proposal would likely decrease inflation in the retail lending ratings

Table 9 below from the agencies’ proposed rule shows the impact of the retail lending test on ratings for that test.[4] Failure rates would increase significantly, ranging from 10% for smaller banks to 4% for banks with assets of more than $50 billion (annual failure rates are now 2% or less). Similarly, the percentage of barely passing or low satisfactory ratings ranges from 46% to 58%. Lastly, no bank with more than $50 billion in assets would be projected to receive an Outstanding rating, which would seem appropriate given BM’s analysis and other work showing that the largest banks have diminished lending performance.[5] This proposal does not seem like a regime that would continue the current ratings inflation.

If one remained concerned about inflation, one could adjust the thresholds corresponding to ratings categories described above. For example, the threshold for High Satisfactory for the community benchmark could be increased from 90% to 100%. Alternatively, the weight of the community or market benchmark could be adjusted. This is the type of fine tuning that could occur after a few years following a final rule. NCRC had recommended that the agencies revisit their CRA rule approximately once every five years for this type of fine tuning, which would most likely make exams more rigorous, better able to accommodate changes in demographics or lending practices, and more likely to achieve more consensus among stakeholders regarding the fairness and adaptability of exams. More frequent adjustments, while creating some anxiety among stakeholders, are still preferable to more massive changes once every two or three decades.

BM’s critique of the lending test misses the mark, and their proposed solutions will not effectively work as a better alternative

The BM letter, on the other hand, would throw out the community benchmark since it concludes that this benchmark does not have much meaning.[6] Likewise, BM does not approve of the proposed rule that a bank must pass in at least 60% of its assessment areas for it to pass overall, calling this proposal arbitrary.[7] This assertion is hard to understand. A bank should pass in most of its assessment areas in order to ensure that it is serving needs across the variety of geographical areas it serves, which is what CRA requires them to do. NCRC had proposed that a bank must pass in 70% of its assessment areas or at least in 60% of its rural counties, smaller metropolitan areas, and largest metropolitan areas considered separately in order to ensure that it is meeting needs regardless of the size or urban/rural nature of the areas.[8]

BM is concerned about banks gaming their lending activity and avoiding serving needs in areas in which it is harder to do so. Yet BM does not offer a proposal that would serve as a better alternative to either the agencies’ or NCRC’s for avoiding gaming, to the extent that such gaming exists.

BM calculates that if the community benchmark and proposal to pick the lower of the community benchmark or market benchmark are eliminated, then the failure rate increases from 23% to 60% of home loan volume. But BM does not translate the loan volume calculation into the actual number or percentage of banks failing the home loan retail test, making it hard to compare against the agencies’ projections. When BM removes the 60% pass rate rule, the failure rate drops to 20%, which is approximately the projected rate for the agency proposal.[9] Why BM would want to do this in unclear, since they criticize the agency failure rate as too low, and as stated above NCRC disagrees with BM regarding the rationale of the 60% rule. In sum, BM adjusts the lending test using different measures, but it seems that their results are no better and likely worse than the agencies’ proposal.

BM asserts that a bank could seek to minimize its lending to low- and moderate-income borrowers by seeking out geographical areas with low levels of loans-to-deposits (one of thresholds in the lending test) or low community or market benchmarks.[10] Of course, a bank can engage in this type of manipulative behavior. In practice, relatively few banks would likely behave this way since pursuing profitable loans across geographical markets is a more powerful motivation for most lenders rather than minimizing loans to low- and moderate-income borrowers. However, to the extent gaming behavior does exist, BM does not offer a clear method for defeating it. Instead, it mainly criticizes the 60% pass rule as arbitrary.

BM seems to be proposing a lending test with only the market benchmark and with more weighting for geographical areas that have low lending levels relative to the population of low- and moderate-income households. BM favors discarding the community benchmark because it does not adequately measure demand. However, the agencies are not using this benchmark only as a proxy for demand. Instead, it is a measure of the extent to which banks are reaching traditionally underserved populations. Removing it amounts to measuring CRA performance in a vacuum without any reference to the demographics or needs of communities.

To replace the community benchmark, BM would provide more weight for scores in geographical areas in which the level of lending is low relative to the low- and moderate-income population. This would be a ratio of loans to the low- and moderate-income population. However, despite BM’s assertions, it is not clear that this ratio measures demand. Low ratios may not translate into banks not meeting demand. Instead, in some geographical areas, it is harder to lend to low- and moderate-income populations.

Like BM, NCRC is concerned about underserved areas. However, we proposed a specific measure on the lending test instead of weighing an entire lending test rating for a geographical area based on this ratio. Our approach is less arbitrary and would reduce the chances of penalizing banks for factors beyond their control (such as high cost of housing or differences across geographical areas in the creditworthiness of low- and moderate-income populations). Specifically, NCRC proposed that the agencies compare a bank’s performance in underserved census tracts against their peers as an additional measure on the lending test. An underserved tract would be defined as low levels of lending compared to households and would include several predominantly minority tracts.[11]

In addition, BM asserts that the proposed loan-to-deposit ratio will mask redlining by banks.[12] When this ratio declines in a geographical area, a particular bank with a low ratio will appear to be performing in at least a passing manner when compared to all banks that also have low ratios. However, this analysis misses how this ratio is used. It is not used to screen for redlining but to ensure that banks are lending out their deposits. NCRC suggested in our comment letter that the proposed threshold for passing this ratio of 30% of the bank aggregate in a geographical area is too low and should be raised to at least 60%.[13]

To fault this ratio as an inadequate screen against redlining amounts to a misunderstanding of the ratio. Instead, the method for measuring redlining is to compare a bank’s percentage of loans in communities of colors against its peers. Low percentages merit more investigation including spatial analysis using maps. This is how the bank agencies and the Department of Justice have been conducting fair lending investigations for decades. They continue to prosecute redlining cases including those involving referrals by community organizations.

BM also complains that CRA exams only compare banks at a point in time, not over a time period.[14] This is not accurate. CRA exams often compare performance over two or three years. BM would seem to want CRA exams to include several years of performance to guard against overall declines in lending by all banks. While their concern is legitimate, that type of approach is not feasible and would result in exams that are already a few hundred pages becoming thousands of pages long and being too dense to be useful for community organizations and other stakeholders. Instead, exams should occur every two or three years in order to maintain bank accountability to communities. Overall declines in lending can be dealt with by improved performance context analysis and/or tightening the thresholds discussed above if the agencies and stakeholders believe that banks are underperforming given economic conditions.

Conclusion

BM ends its letter with a declaration that the low level of homeownership among low- and moderate-income households coupled with increasing CRA pass rates for banks suggests that CRA enforcement has failed.[15] NCRC agrees that CRA needs to be strengthened along the lines suggested in our comment letter. However, BM’s accusation cannot withstand scrutiny. It ignores broader economic trends such as wage stagnation particularly for lower income workers and the impact of the subprime lending crisis and the Great Recession, which caused massive declines in homeownership among vulnerable populations. The main culprits were non-CRA regulated and lightly regulated independent mortgage companies with financial assistance from non-CRA covered investment bank arms of bank holding companies.

In addition, the BM letter ignores important research sponsored by the Federal Reserve Banks, which shows that CRA has increased home mortgage lending, small business lending, and branching in low- and moderate-income tracts.[16] It is likely that without CRA, the homeownership rate for low- and moderate-income households would have plunged even further.

Banks can do better in making responsible home loans to low- and moderate-income borrowers. NCRC believes that enhancing the proposed rule is the better approach rather than declaring it will fail at the outset. Moreover, enhancing the proposed rule will build upon the carefully documented benefits of CRA in terms of increased reinvestment.

Thank you for consideration of our views. If you have any questions, please contact me at jvantol@ncrc.org or Josh Silver, Senior Fellow, at jsilver97@gmail.com.

Sincerely,

Jesse Van Tol

President and CEO

[1] Office of the Comptroller of the Currency, Federal Reserve Board, Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, Notice of Proposed Rulemaking (NPR) to amend the CRA regulations, May 5, 2022, issued version, https://www.federalreserve.gov/consumerscommunities/files/cra-npr-fr-notice-20220505.pdf, p. 215.

[2] NPR, p. 251.

[3] NPR, p. 216.

[4] NPR, p. 251.

[5] Better Markets (BM), Supplemental Filing Regarding the Community Reinvestment Act (CRA) Proposed Rule Reviewing Fed Data Demonstrating that the CRA Rule Will Not Work and Redlining Will Continue, August 7, 2023, p. 6.

[6] BM Filing, p. 9.

[7] BM Filing, p. 13.

[8] NCRC’s Full Public Comment Letter On Community Reinvestment Act Interagency Rulemaking, August 4, 2022, https://ncrc.org/ncrcs-full-public-comment-letter-on-community-reinvestment-act-interagency-rulemaking/, p. 112.

[9] BM Filing, p. 13.

[10] BM Filing, p. 15

[11] NCRC comment letter, p. 13.

[12] BM Filing, p. 8.

[13] NCRC comment letter, p. 70.

[14] BM Filing, p. 7.

[15] BM Filing, p. 21.

[16] Kyle DeMaria and Lei Ding, Federal Reserve Study Finds Evidence of Significant Impact of the Community Reinvestment Act, Summar 2017, Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia, https://www.philadelphiafed.org/community-development/housing-and-neighborhoods/federal-reserve-study-finds-evidence-of-significant-impact-of-the-community-reinvestment-act, Lei Ding, Hyojung Lee, and Raphael W. Bostic, Effects of the Community Reinvestment Act (CRA) on Small Business Lending, December 2018, Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia, https://www.philadelphiafed.org/community-development/credit-and-capital/effects-of-the-community-reinvestment-act-cra-on-small-business-lending, Lei Ding and Carolina K. Reid, The Community Reinvestment Act (CRA) and Bank Branching Patterns, Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia, September 2019, https://www.philadelphiafed.org/community-development/credit-and-capital/the-community-reinvestment-act-cra-and-bank-branching-patterns