The Racial Wealth Gap 1992 to 2022

October 2024

Joseph Dean, Racial Economic Junior Research Specialist, NCRC

— Summary

Black households are increasingly dependent on homeownership as a wealth-building strategy. Yet homeownership is out of reach for most low- and moderate-income (LMI) families. Black households in particular also lack liquid assets, which compounds the effects of homeownership disparities – and which helps explain why the Black/White wealth gap has changed little since 1992. To make progress in narrowing the racial wealth gap, governments should enact policies to make housing more affordable and promote homeownership, facilitate entrepreneurship and enable Black and Hispanic Americans to better save for retirement.

— Key Takeaways

Persistent Racial Wealth Gap: The racial wealth gap between median Black and White households has remained virtually unchanged from 1992 to 2022. While there has been some narrowing of the Hispanic/White wealth gap, it remains significant and far from parity.

Dependence on Homeownership: The wealth of Black and Hispanic households is increasingly reliant on homeownership. This concentration in home equity makes their economic position more fragile and more susceptible to market fluctuations.

Insufficient Liquid Assets: Two-thirds of Black and Hispanic households lack sufficient liquid assets to sustain themselves at the poverty level for three months. This financial vulnerability exacerbates their economic insecurity.

Introduction

The average American’s daily life experience has changed dramatically in the past three decades, to a degree rare in the country’s brief history. Nearly every element of day-to-day life in the 2020s would be unrecognizable to a time traveler from 1989, thanks to the compound effects of the end of the Cold War, the start of the Global War on Terror and the digital revolution that, among other things, enabled ambitious social justice movements and extremist backlashes to them.

Yet despite rapid social change, racial segregation and economic disparity remain frustratingly prevalent. For all that abstract upheaval, the hard numbers on entrenched racialized poverty are stubbornly static, as this report shows – using data that begins when the police beating of Rodney King brought civil unrest around the country and ends two years after the police murder of George Floyd did the same.

The vast and persistent wealth gap between African Americans and other Americans reflects inadequate economic empowerment. The roots of this wealth gap lie in chattel slavery, an institution that simultaneously created a new demographic group and deprived its members entirely: Slavery stripped African Americans not only of their freedom and self-determination but of opportunities to build wealth and foster community development. Despite ending over 150 years ago, the effects of this “peculiar” institution,[1] as it was referred to by many slaveholders, continue to exacerbate the racial wealth gap today. While many racialized wealth gaps exist, none are as entrenched and persistent as the gap between African Americans and White people.

Throughout US history, various groups have faced exclusion based on race, religion, or national origin. But Eastern Europeans, Italians and Irish immigrants were eventually accepted as Americans as the concept of ‘Whiteness’ expanded.[2] A nation born of protestant separatism eventually even accepted Catholics. Other groups, like Jews and some Hispanic and Asian communities, have also made gains in wealth and acceptance to varying extents.[3] Unlike the aforementioned groups, Native Americans were driven from their lands that were settled by these various European ethnic groupings who were or became “White.” With much lower income, levels of education, and higher rates of poverty, Native Americans generally have lower household wealth and continue to face exclusion and barriers from the financial system.

The history of African Americans in the US is distinct from these other groups. The poverty and disadvantage faced by African Americans are deeply and irrevocably linked to the history of slavery, and were then compounded by Jim Crow segregation and other forms of legal and illegal discrimination. These discriminatory practices were intentional efforts to maintain a racial hierarchy, contributing to the persistent racial wealth gap this report examines.[4] This wealth gap, marked by the disparity in net assets held by non-Hispanic White households compared to Black and Hispanic households, undermines the economic security of individuals and weakens our economy as a whole. The insecurity represented in data on the wealth gap also actively enforces that gap, perpetuating the concentration of wealth within the expanded concept of White America.[5]

Those on the wrong side of the racialized wealth gap do not only live materially worse lives when times are steady. The gap also limits the economic “cushion” protecting their households during difficult financial times. The racial wealth gap restricts the educational,[6] employment and business opportunities of Black and Hispanic households,[7] impacting their well-being and putting a brake on our economic development as a society. The racial wealth gap must be addressed as a matter of equity in the movement toward a just economy.

The historical factors contributing to the racial wealth gap are well documented. One driver, racial discrimination, is multifaceted and some of the ways in which it manifests itself include discriminatory lending practices,[8] residential segregation[9] and labor market discrimination. Differences in income, culminating in the income gap, are another factor.[10] Finally, intergenerational transfers are also a driver of the racial wealth gap.[11] Since Black and Hispanic households hold less wealth, there are fewer assets to pass down to family members compounding the racial wealth gap across generations.[12]

Tracking the persistent wealth gap between Black, Hispanic and White households is challenging due to the complexity of asset holdings and the need for consistent methods of analysis. This report uses new data[13] from the Survey of Consumer Finances (SCF) to closely examine the racial wealth gap- with the difference in the assets owned such as homes, businesses, money or other valuables, between Black, Hispanic and White families in America between 1992 and 2022.

The Federal Reserve Board’s triennial SCF is one of the most comprehensive and consistent sources of wealth data. It provides insights into the kinds of assets and debts households hold and how the distribution of wealth has changed over time. Using the SCF we will look at how the balance sheets of households both differ by race, the prevalence of asset poverty and the relationship between homeownership and the racial wealth gap.

An Overview of the Racial Wealth Gap

Figure 1

The latest SCF data shows that the racial wealth gap remains a fixture of our society.

In 2022, the median White household held $284,310 in wealth,[14] more than six times that of the median Black household at $44,100 and 4 times that of Hispanic households at $62,120. Black households have a wealth gap of 85% compared to White households, and Hispanic households have a wealth gap of 78%.

To understand the magnitude of the racial wealth gap consider this: The wealthiest 80% of Black and Hispanic households own less wealth than the median White household. On the flip side, a White household at the 25th percentile mark (meaning if 100 White households are lined up based on net worth, 24 have less in wealth than them) has $64,561 in net worth. That is still more than the median Black and Hispanic household ($44,100 and $62,120). Juxtapose this with the fact that at the 25th percentile mark, Black and Hispanic households have $1,850 and $9,450, respectively, and you get a better understanding of the scale of the racial wealth gap.

While household wealth has grown since the pandemic, the wealth gap has stubbornly remained. In 2019, the median wealth for White households was $219,206, while Black households had $27,937 and Hispanic households had $41,789. At that time, Black households faced an 87% wealth gap, and Hispanic households faced an 81% wealth gap compared to White households.

Hispanic households are narrowing their gap to White households, but Black households are not. Way back in 1992, the Hispanic-White median wealth gap was 90% – and while a 9 percentage point narrowing in 30 years is hardly a sufficient rate of progress, that shift is positively eye-popping compared to the Black wealth experience over the same timeframe. The Black-White median wealth gap was 86% in 1992, and 85% in 2022.

This persistent disparity underscores deep-rooted economic inequalities that not only harm America as a whole but also devastate Black and Hispanic communities.

The wealth of Black and Hispanic households has also become less diversified in recent years. Families of color are more dependent on homeownership. In 2013, the percentage of Black and Hispanic wealth tied to home equity was 33% and 37%, respectively. In 2022, Black and Hispanic households derived 44% and 45% of their wealth from home equity. However, for White households home equity accounts for about 19% in net worth in 2022, roughly the same percentage as it did in 2013.

The concentration of Black and Hispanic wealth in home equity in 2022 is historically unprecedented. Each group was far less reliant on their homes for wealth in 1992, when 38% and 33% of the Black and Hispanic wealth was tied to home equity. Even in 2007, right at the peak of the housing bubble, the percentage was between 39%-40% for both groups. Contrasting this with the fact that home equity rarely accounted for more than 25% of White household wealth underscores the need to diversify POC wealth. While homeownership is one of the best ways for the typical American to build wealth, the concentration of wealth in home equity can make households more susceptible to economic shocks.[15]

Figure 2

Figure 3

Figure 4

This dependence on home equity is even more pronounced when looking at which assets contributed to net wealth gains. From 2013 to 2022, housing equity alone accounts for more than two-thirds of the net change in both Black and Hispanic median wealth. For White households, increasing home equity only made up 25% of the gain in wealth.

These numbers also suggest that the rise in median Black wealth is primarily due to rising home prices over that time – a large benefit accruing to a small share of Black people – rather than indicative of a broadening of opportunity for Black America writ large. More than 90% of total Black wealth gains went to the 46% of Black households who own a home. This means the recent, sudden three-year spike in home equity for Black homeowners – an almost 60% rise from 2019 to 2022 – went to less than half of Black households.

Undiversified assets present a problem for minority households’ accumulation of wealth. White households’ net wealth gains from 2019 to 2022 were evenly distributed across increases in home equity, business assets and retirement assets. This diversification in sources is largely absent for Black and Hispanic households. For Black households, business assets (20.8%) and vehicles (17.6%) were the second and third largest contributors to changes in net worth. For Hispanic households, retirement (16.5%) and business assets (15.3%) were the second and third largest contributors to wealth gains.

This lack of diversification has been a long-term problem for Black and Hispanic households. From 1992 to 2022, nearly half of the total increase in Black and Hispanic wealth came from home equity alone. Nearly 80% of it came from home equity and retirement holdings combined. While a retirement account and a paid-off home are the basis of the ‘American Dream’ of retirement, similarly situated White households are more diversified in their wealth – and have been throughout our three-decade period of analysis. This leaves Black and Hispanic households at a disadvantage regarding emergencies and repairs.

The median value of stock holdings (counted as holdings separate from retirement accounts) dropped for all groups from 2019 to 2022, but the falloff was especially dramatic for Black and Hispanic American households, falling 64% and 65%, while decreasing 42% for White households. These declines can partially be attributed to the simultaneous increases in new households acquiring stocks, albeit in lower amounts. The combination of pandemic stimulus, social isolation and the proliferation of micro-trading apps led to more households owning stock than ever.[16] There was a 96% and 85% increase in the number of Black and Hispanic households, respectively, holding stocks, but overall low levels of ownership and financial returns from stock-linked assets made a negligible contribution to wealth gains for the two minority groups.[17]

Wealth, Homeownership and the Racial Wealth Gap

Figure 5

Black and Hispanic homebuyers have lower incomes and less cash to spend on homes. That makes it harder to pay closing costs, and often forces those who can buy at all to purchase homes worth less than those purchased by White homebuyers. That fundamentally dimmer value proposition is compounded at closing: Black and Hispanic homebuyers pay more in closing costs both in raw dollars and as a percentage of their incomes.

This situation severely limits the potential of homeownership to close the racial wealth gap: Because non-White homebuyers are more leveraged on less value, the overall wealth effects of ownership are less efficient. Homeownership is often talked about as a key “growth engine,” but in that metaphor, White homebuyers are driving a finely tuned sports car while others ride mopeds.

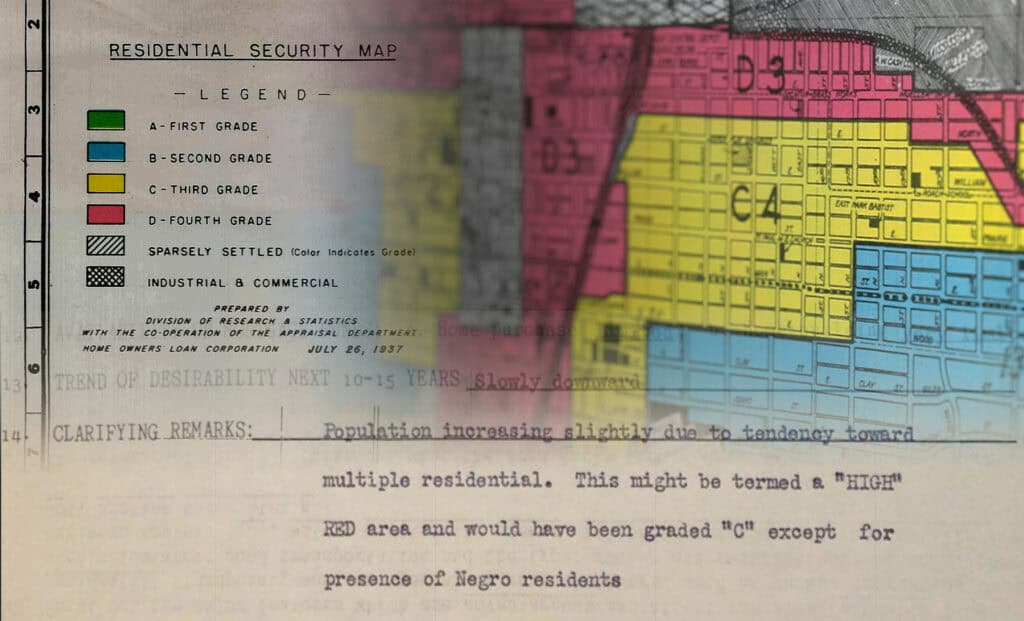

Even when Black and Hispanic families achieve homeownership, they do not experience the same return on investment as White families. This disparity stems from various factors, including appraisal bias and systemic racism in the real estate industry.[18] Appraisal bias can manifest as direct racism, where appraisers undervalue homes based on the owner’s race or the racial composition of the community.[19] This practice dates back to the 1930s with the Home Owner’s Loan Corporation (HOLC) and continued with the Federal Housing Administration (FHA), perpetuating residential segregation and devaluing homes in redlined communities.[20]

Appraisal bias can also be a symptom of segregation. Automated valuation models (AVMs) use algorithms that look at nearby homes to judge the value of your home. If you live in a neighborhood that was historically denied access to mortgages, your home value will reflect that. AVMs are used by your local property appraiser, but commercial versions (like Zillow’s ‘Zestimate’) also use a version of this method. As Artificial Intelligence (AI) is incorporated into these tools there is both a threat and an opportunity. AI can be trained to recognize the impact of redlining and segregation and address it fairly, but only if we are first aware of the impact of existing segregation and bias on homes and wealth.

Steering and outright racism by real estate agents and homeowners, including discouragement at the start of the mortgage application process and showing homes in segregated areas, remain pervasive in the industry.[21] Consequently, Black and Hispanic families report lower home values compared to White buyers.

Figure 6

In 2023 the average White buyer purchased an asset worth over $450,000. At closing they had over $130,000 in equity, or wealth that they could then invest in other ways. While Black and Hispanic homeowners can do likewise with their starting equity, they have far less of it – and what they do have at closing is tied to a home that is worth less.

The racial differential in how effectively homeownership translates into long-term wealth is a longstanding concern for policymakers and advocates interested in closing the racial wealth gap. It should be even more alarming given the SCF data discussed above showing that Black and Hispanic wealth gains are overwhelmingly concentrated in home equity.

Thus, we face two challenges: increasing homeownership among Black and Hispanic communities and diversifying their asset holdings.

Liquid Assets, Financial Resources and Marketable Wealth

In economics textbooks, wealth is just the difference between assets and liabilities. In real life, it is also what determines a household’s ability to cover unexpected expenses – and not all types of wealth are equivalent for surviving emergencies. To better understand what resources are available to families we look at wealth using three different combinations of assets. In order from least to most restrictive, the three measures we use are marketable wealth, financial resources and liquid assets.

The first two of our clusters – “non-depreciating wealth” and “financial resources” – are different definitions of net worth. The third cluster is “liquid assets.” Each of the three aims to better capture the real-world scenarios involved in dealing with unexpected emergency expenses.

Non-depreciating wealth is net worth minus vehicles and is designed to capture wealth that does not decline in value over time. Because vehicle values decline the more they are driven (they depreciate over time), capturing non-depreciating assets would provide a more realistic picture of wealth than net worth overall. Black, and to a lesser extent Hispanic, households have grown more reliant on vehicles to boost wealth.

Black median marketable wealth is about 58% of overall Black median net worth, a low ratio that emphasizes how tightly Black household net worth is tied to vehicles. White median marketable wealth is 88% of overall White median net worth.

It is further worrying that vehicles contributed close to 18% of Black households’ wealth gains from 2019 to 2022. Those gains are unlikely to be sustainable if they rely on depreciating assets, rather than on increasing homeownership and other drivers of non-depreciating wealth.

Figure 7

The next measure, financial resources, is net worth minus vehicles and home equity. Because selling one’s home or vehicle incurs significant lifestyle changes, this definition of net worth is designed to capture all resources that are available for emergency use without diminishing one’s standard of living. There’s a 99% gap in financial resources between Black and Hispanic and White households, higher than the overall racial wealth gap.

At just $670 and $400, respectively, financial resources for Black and Hispanic households are minuscule compared to the $73,200 White households held in 2022. Even worse, these paltry sums are down from 2019 for Black and Hispanic households. This decline is due, in part, to (1) the outsized role housing plays in Black wealth and (2) the temporary and synthetic increase in vehicle values as car prices soared during the pandemic. Home equity and vehicles accounted for 86% of the growth in Black household net worth between 2019 and 2022. Like marketable wealth, the decline in financial resources highlights the shaky foundations of Black and Hispanic wealth and the necessity of diversification.

Figure 8

Finally, liquid assets are the readily available money that the family can spend when they need it. This means cash, either in physical form or in a checking or savings account. This is the first place people turn to when they need to pay an unexpected bill or cover an unplanned cost. Without sufficient liquid funds available, families are highly vulnerable to predatory and/or value-stripping sources of quick cash such as payday lenders, car title companies and even housing cash buyers.

Figure 9

Liquid asset poverty is the inability of a household to subsist entirely on liquid assets at the federal poverty level for three months without an income. We use the checking and savings account balances of households in SCF to calculate liquid asset poverty.[22]

Liquid asset poverty has been on the decline over the last decade, yet remains pervasive among Black and Hispanic households. In 2022, over two-thirds were liquid asset-poor. This means that two-thirds of Black and Hispanic households, or roughly 70 million people, do not have enough money in their checking and savings accounts to live even a subsistence lifestyle for three months. Furthermore, 30% and 35% of Black and Hispanic households reported less than $1,000 in liquid assets, compared to 11% of White households.

Increase Homeownership and Diversify Assets to Close the Racial Wealth Gap

Nearly 160 years after the end of chattel slavery, the racial wealth gap remains massive. At least as alarming, however, is that it remains so durably massive even six decades after Black people obtained the full rights of citizenship. These are not only policy failures but a colossal societal failure.

On our current trajectory, it would take at least five centuries to close the Black-White wealth divide[23] – more than twice as long as the United States of America has existed. Efforts to address the racial wealth gap will have to confront the many centuries of enslavement and disenfranchisement that produced it. One measure should of course be to increase the homeownership rate of Black and Hispanic households, because the home is typically the most valuable asset a family owns.

But this report also highlights that the size of the racial wealth gap varies depending on the kinds of assets that count as a part of wealth. Whether we include all assets, only non-depreciating assets, or just liquid assets, the gap remains – and indeed worsens the further away from homeownership the measuring technique shifts.

This suggests a second policy conclusion beyond NCRC’s longstanding advocacy for efforts to boost homeownership for people of color. Local and national leaders must also work to simultaneously diversify the asset holdings of Black and Hispanic households.

Owning a home is fantastic. Yet the dependence on home equity to boost wealth comes with significant drawbacks. It is partly why the late-2000s crash brought on by deregulated Wall Street’s casino-like misconduct was more financially debilitating for Black and Hispanic households than White households,[24] despite White households being much more likely to own homes during a crisis centered in the housing market.

The lack of affordable housing supply is a significant factor contributing to the racial homeownership gap in the United States. Reports from various initiatives highlight this issue in Washington, Oregon and the District of Columbia. The Washington State Homeownership Disparities Work Group’s report indicated that over 140,000 homes need to be purchased by Black, Indigenous and people of color (BIPOC) to achieve homeownership parity with White households in the state. This gap is attributed to systemic barriers such as discriminatory policies, limited access to credit and the scarcity of affordable housing options. The report offered 27 recommendations to address these disparities, including increasing state funding for affordable homeownership programs, providing technical assistance to municipalities and expanding debt mediation and credit repair programs.

Similarly, the Oregon Task Force on Addressing Racial Disparities in Home Ownership emphasized the need for comprehensive strategies to improve homeownership rates among BIPOC communities. Recommendations from these initiatives focus on policy revisions, financial assistance and targeted outreach to ensure equitable access to homeownership.

The Seattle Housing Development Consortium’s Black Homeownership Initiative also works towards increasing Black homeownership through community-driven solutions and policy advocacy. These coordinated efforts reflect a growing recognition of the need to dismantle the historical and systemic barriers that have long prevented equitable access to homeownership for marginalized communities.

The District of Columbia’s Black Homeownership Strike Force was tasked with making recommendations to the Mayor on how to use a $10 million Black Homeownership Fund designed to increase Black Homeownership by 20,000 homeowners by 2030. They gave recommendations on how to boost homeownership and keep new homeowners in their homes.

The DC task force echoed some of the suggestions out of Washington state, such as increasing the housing supply by introducing legislation to curb housing speculation, redevelop District-owned properties and make them available for low-income homebuyers, and soften zoning and permitting requirements. To keep Black homebuyers in their homes, they suggest providing estate planning and legal services and home repair assistance

One of the common recommendations shared by the different task forces was to utilize special purpose credit programs (SPCPs). These allow banks to extend credit to disadvantaged borrowers on favorable terms. The Equal Credit Opportunity Act (ECOA), which prohibits creditors from discriminating against credit applicants, has a provision allowing SPCPs. To meet the requirements of ECOA creditors must, among other requirements, show that the SPCP will benefit a class of people that would not receive credit, or pay too much for it, under traditional credit standards.

In 2020 the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau recommended lenders use a wide range of data and research to analyze whether an SPCP meets its eligibility requirements. The interpretative rule (IR) specifically cites HMDA as a potential data source. Because the IR states that lenders can utilize historical data, they could use the HOLC redlining maps to connect historically redlined neighborhoods with current HMDA data to argue that there is a need that meets the CFPB’s requirements.

These and other valuable initiatives could help chip away at the homeownership gap. But if non-White families are also going to escape the diversification trap detailed above, policymakers and business leaders need to widen their gaze: Wealth-building requires a stable, and ideally rising, income.

Here policies such as universal basic income, universal jobs programs and the revitalization of labor unions can provide an anchor for households that cannot currently afford to amass assets, let alone figure out how to diversify those holdings. Baby bonds, first laid out in 2010 by a pair of veteran researchers, are publicly funded child trust accounts to later be used in adulthood for wealth-building activities such as purchasing a home or starting a business.

Reparations

Today’s Black-White racial wealth gap is part of the legacy of America’s original sin: the institution of chattel slavery. It took the triumph of the Union Army, by then a liberating force, to overthrow slavery and make possible what we have come to call ‘40 acres and a mule,’ or reparations.

Reconstruction, the period following the end of Civil War, was intended to redress the wrongs of slavery, reorganize the Southern economy and assimilate millions of freed people. Reconstruction authorities sought to seize the land of former Confederate leaders and seditious slave owners and resettle freedmen, poor Whites and their families. These efforts failed – and other grand Reconstruction-era promises made to former slaves and their descendants came to nothing as well. That failure and the eventual overthrow of Reconstruction marked the last major effort to implement reparations– until today.

In recent years, several localities have implemented some form of cash reparations for descendants of slaves. Thus far this policy solution remains both the most forward-thinking of solutions to the racial wealth gap, and vexing for the country to implement. Reparations should not just be viewed as a way to address past harms but should be linked to constructing a new democratic order for the future, that tackles issues of racial economic inequality alongside sister issues of climate change which disproportionately harm communities of color.

Local, state and federal leaders may land on different mixtures of the above policies as they work to address the racial wealth gap. But whatever pieces of the picture they might pick up or leave aside, one thing is clear: What we have been doing until now is not working. From Rodney King’s beating to George Floyd’s murder, three decades of public policy and private business practice have made essentially no dent in the problem.

Thoughtful institutions may come to entirely different, wholly reasonable conclusions about which combination of reparations, baby bonds, income supports, labor policies, and housing reforms are appropriate to their constituency.

The one thing that is not reasonable is settling for more of the same.

References

Aliprantis, D., Carroll, D., & Young, E. R. (2022). The Dynamics of the Racial Wealth Gap. Working Paper No. 19-18R. Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland.

Derenoncourt, E., Kim, C. H., Kuhn, M., & Schularick, M. (2023). Changes in the Distribution of Black and White Wealth since the US Civil War. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 37 (4): 71-90.

Grinstein-Weiss, M., Key, C., & Carrillo, S. (2015). Homeownership, the great recession, and wealth: Evidence from the survey of consumer finances. Housing Policy Debate, 25(3), 419-445.

Levine, P. B., & Ritter, D. (2024). The racial wealth gap, financial aid, and college access. Journal of Policy Analysis and Management, 43(2), 555-581

Lin, K. H., & Dominguez, G. (2023). The Rising Importance of Stock-Linked Assets in the Black–White Wealth Gap. Demography, 60(6), 1877-1901.

McKernan S. M., Ratcliffe, C., Simms, M., & Zhang, S. (2014). Do racial disparities in private transfers help explain the racial wealth gap? New evidence from longitudinal data. Demography, 51(3), 949-974.

Ray, R. et al., 2021. Homeownership, racial segregation, and policy solutions to racial wealth equity, Brookings Institution. United States of America

Pantin, P., & Lynnise, E. (2017). The wealth gap and the racial disparities in the startup ecosystem. Louis ULJ, 62, 419

Pfeffer, F. T., & Killewald, A. (2019). Intergenerational Wealth Mobility and Racial Inequality. Socius, 5.

Quillian, L., Lee, J. J., & Honoré, B. (2020). Racial discrimination in the US housing and mortgage lending markets: a quantitative review of trends, 1976–2016. Race and Social Problems, 12, 13-28.

Wolff, E. N. (2021). Household wealth trends in the United States, 1962 to 2019: Median wealth rebounds… but not enough. National Bureau of Economic Research.

[1] Amsden, David. “A Peculiar Institution.” The New York Times Magazine, 1 Mar. 2015

[2] Ignatiev, N. (2012). How the Irish became white. Routledge.

[3] Darity et al. (2018). What we get wrong about closing the racial wealth gap. Samuel DuBois Cook Center on Social Equity and Insight Center for Community Economic Development, 1(1), 1-67.

[4] Derenoncourt, E., Kim, C. H., Kuhn, M., & Schularick, M. (2023)

[5] https://home.treasury.gov/news/featured-stories/racial-differences-economic-security-racial-wealth-gap

[6] Levine, P. B., & Ritter, D. (2024)

[7] Pantin, P., & Lynnise, E. (2017)

[8] Quillian, L., Lee, J. J., & Honoré, B. (2020)

[9] Ray, R. et al., 2021

[10] Aliprantis, Dionissi, Daniel R. Carroll, and Eric R. Young. 2022

[11] McKernan, S. M., Ratcliffe, C., Simms, M., & Zhang, S. (2014). Do racial disparities in private transfers help explain the racial wealth gap? New evidence from longitudinal data. Demography, 51(3), 949-974.

[12] Pfeffer, F. T., & Killewald, A. (2019)

[13] Data from 1992 to 2022 is presented here though the data starts in 1989

[14] Net worth is the total sum of assets minus liabilities. We use ‘wealth’ and net worth interchangeable unless noted.

[15] Grinstein-Weiss, M., Key, C., & Carrillo, S. (2015). Homeownership, the great recession, and wealth: Evidence from the survey of consumer finances. Housing Policy Debate, 25(3), 419-445. https://www.stlouisfed.org/-/media/project/frbstl/stlouisfed/files/pdfs/hfs/20130205/papers/grinsteinweiss_paper.pdf

[16] https://www.wsj.com/finance/stocks/stocks-americans-own-most-ever-9f6fd963

[17]Lin, K. H., & Dominguez, G. (2023). The Rising Importance of Stock-Linked Assets in the Black–White Wealth Gap. Demography, 60(6), 1877-1901.

[18] Squires, G. D., & Goldstein, I. (2021). Property Valuation, Appraisals, and Racial Wealth Disparities. Poverty & Race Research Action Council, 2(30), 1-4.

[19] Lilien, Jake (2022). Faulty Foundations: Mystery-Shopper Testing In Home Appraisals Exposes Racial Bias Undermining Black Wealth. National Community Reinvestment Coalition

[20] For an overview of the HOLC redlining maps see: Mitchell B. & Franco J (2018). OLC “Redlining” Maps: The Persistent Structure Of Segregation And Economic Inequality. National Community Reinvestment Coalition

[21] Hall, M., Timberlake, J. M., & Johns-Wolfe, E. (2023). Racial Steering in U.S. Housing Markets: When, Where, and to Whom Does It Occur? Socius, 9.

[22] The federal poverty level guidelines are issued by the HHS every year and are used to determine eligibility of certain income-based public programs. The federal poverty level is dependent on the size of the household. The historical federal poverty guidelines used for our asset poverty calculation are found at: https://aspe.hhs.gov/topics/poverty-economic-mobility/poverty-guidelines/prior-hhs-poverty-guidelines-federal-register-references

[23] Muhammad, D & Collins, C & Ocampo, O & Sim, S (2023). Still a Dream: Over 500 Years to Black Economic Equality. National Community Reinvestment Coalition/ Institute for Policy Studies

[24] Addo, F. R., & Darity, W. A. (2021). Disparate Recoveries: Wealth, Race, and the Working Class after the Great Recession. The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 695(1), 173-192. https://doi.org/10.1177/00027162211028822

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Subscribe

Get NCRC news and

alerts by email.