Addressing the Needs of Black-Owned Businesses and Entrepreneurs

Photo: © Andrey Popov via stock.adobe.com

A follow-up report on the impacts of COVID-19 on entrepreneurship in Piedmont, North Carolina.

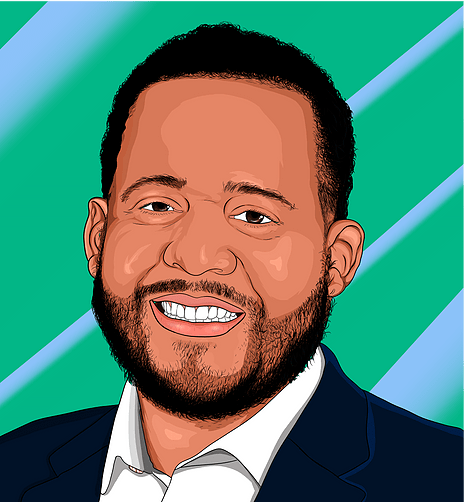

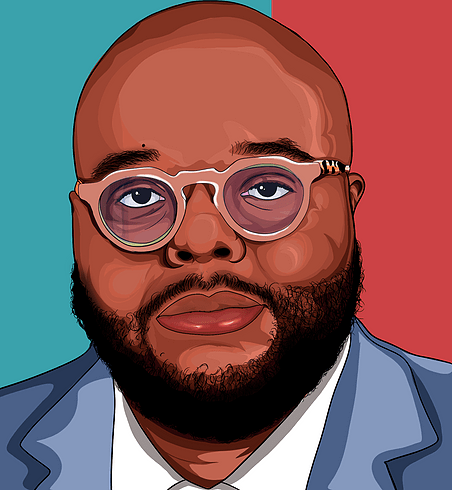

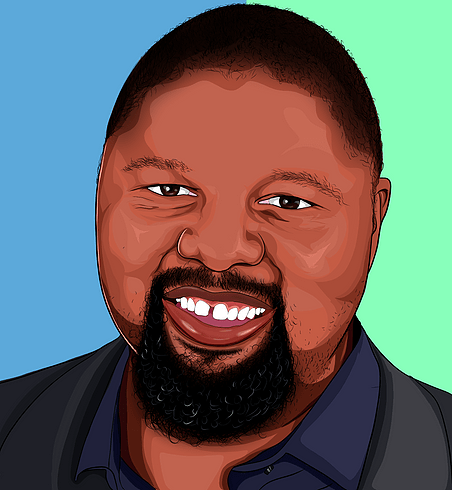

Authors:

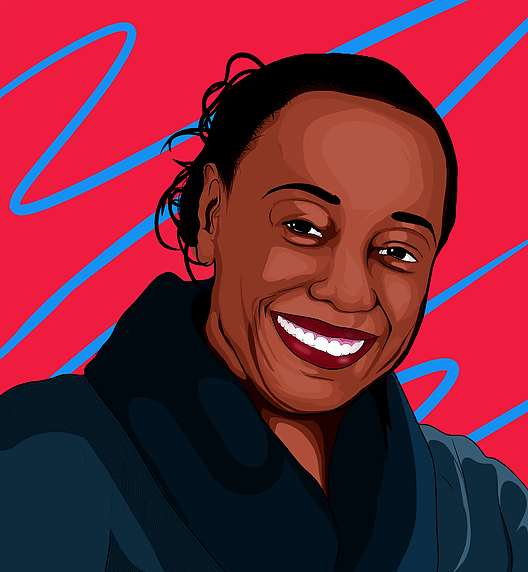

Dedrick Asante-Muhammad, Chief of Membership, Policy and Equity at NCRC

Jamie Buell, Coordinator of Racial Economic Equity at NCRC

Talib Graves-Manns, Co-Founder of Partners in Equity NC

Wilson Lester, Co-Founder of Partners in Equity NC

Napoleon Wallace, Co-Founder of Partners in Equity NC

Key Takeaways

- Despite growth of Black entrepreneurship over the last decade, existing disparities between Black businesses and non-Black businesses is narrowing the pathway to greater employee and revenue growth for these firms.

- The economic consequences of the global pandemic has amplified the disparate and unequal access to financing for Black-owned businesses, causing greater rates of closure and slower recovery than White-owned businesses. In the Piedmont region of North Carolina specifically, Black-owned businesses reported cutting costs, laying off staff and their inability to seek significant capital.

- Historic examples of limited and misaligned support from major financial institutions to Black businesses should be augmented by a renewed investment in local institutions – including Black-owned banks like CDFIs who predominantly serve Black communities -with successful track records.

- Mentorship and collaboration from financial investors within the business ecosystem – a “trusted advisors” model that can work in lock step with entrepreneurs, maximizing growth at every turn – can be more beneficial than the traditional “technical assistance” model.

- To address capital and market access for Black-owned businesses, private and public dollars must pour into pre-seed and seed funds; more capital investment across a business’ life cycle is welcomed; and additional investment in African American communities is needed to acquire and control their own assets.

- North Carolina is uniquely responding to the needs of its Black-owned businesses with the recent launch of N.C. IDEA, a 25-member Black Entrepreneurship Council in effort to supply grants and open doors for minority-owned businesses, and organizations like ResilNC and PIE-NC supporting recovery and sustainability of Black entrepreneurs.

Introduction

Historically, African Americans have played a critical role in the nation’s quest for business innovation. From Madam C.J. Walker’s hair-care line to the 21st century innovators of today, there is a creative class of Black entrepreneurs and owners who carry the legacies of those before them. Prior to the coronavirus pandemic, the nation began to experience growth in African American entrepreneurship. From 1992 to 2017, for instance, the share of total firms that were Black-owned grew from 3% to 9.9%.[1] Black women in particular in recent years represent the highest rate of growth among women-owned businesses.

This pre-pandemic upward trend in Black business and entrepreneurship growth doesn’t negate the persistent disparity between Black businesses and non-Black businesses. The pathway to entrepreneurship for Black business owners is among the most narrow, and employee and revenue growth of existing owners pale in comparison to the greater landscape of business ownership. History and recent growth does, however, call for the need to create stronger ecosystems and targeted resources for Black-owned businesses to leverage for growth. Meeting this imperative speaks not only to the needs and opportunities in business and innovation, but is critical to meaningfully closing the racial wealth divide in this country.

Black businesses are more likely to hire residents in the communities where they live and work than non-minority businesses. Additionally, Black business owners hold nearly 12 times the wealth of African Americans who are not firm owners. Therefore, an investment in a Black entrepreneur and business is an investment in Black communities; in Black families and their ability to climb the economic ladder of opportunity; in our local economy, creating new jobs and in making the case for global competitiveness. According to Brookings, if Black businesses accounted for 14.2% of employer firms – a share of representation comparable to the U.S. Black population at 13.4%, there would be 806,218 more Black businesses; if their average revenue was raised to the level of non-Black businesses, it would increase total revenue in Black businesses by $676 trillion; and if the average employees per Black business increased to 23, it would create approximately 1.6 million jobs.

Although 13.4% of the U.S. population is Black, African American businesses comprise only 9.5% of all business owners, and even worse, African Americans are only 2.2%[2] of all employer businesses. The 2017 Annual Business Survey found that although Black-owned employer and nonemployer firms generate over $193 billion in revenue, this is only 0.5% of total U.S. firm revenue. White-owned firms, for comparison, owned an overwhelming 79.7% of employer and nonemployer firms, and generated nearly $12.6 trillion. This represents 33.5% of total firm revenue.[3]

This report draws from data on the business impacts and economic consequences of the pandemic by highlighting survey insights of entrepreneurs most affected. It looks at examples of successful Black businesses to better understand the most effective means of broadening the path of entrepreneurship for wealth building and economic stability. This is achieved by drawing on historical instances, past individual experiences, anecdotal responses to surveys and data compiled from African American entrepreneurs who have managed to find success in a context where racial economic inequality, the racial wealth divide and a lack of capital for Black businesses continues to greatly limit entrepreneurship as a wealth building activity.

Investors interested in an economy that is no longer marked by deep racial inequality share an aligned interest with the prosperity of the Black business ecosystem. Therefore, funders too must break with the old models and discard inequitable practices and traditions to create this new pathway.

Partners in Equity (PIE-NC), a North Carolina based small business and real estate investment firm, and ResilNC, a small business data and investment collaborative, have partnered with the National Community Reinvestment Coalition to analyze the challenges for African American businesses particularly amid the ongoing pandemic which has already shuddered close to half of the minority-owned businesses in operation prior to COVID-19.

Over the last 20 years, there has been limited advancement in African American entrepreneurship and so a more intentional, targeted approach must be created for the immediate needs and the future stability of Black business owners previously neglected or actively dissuaded from reaching their full potential.

“We have a government and financial system that has been discriminatory against Black businesses and denied Black people – for decades – access to capital and financial means… you can’t overcome that with a feel good conversation.”

Gerry M.

The Data:

National Implications of the Pandemic on Minority-Owned Small Businesses

Photo: ©JonoErasmus – stock.adobe.com

A report published in August 2020 by the New York Federal Reserve Bank (NYFR) concluded that 40% of all receipts from Black-owned businesses are concentrated in 30 U.S. counties.

Those same counties –– 11% of all U.S. counties –– were at the time of the report among those hardest hit by COVID-19. The well-documented health disparities in the pandemic’s effects on minority populations, specifically Black and Hispanic populations, are as true in the entrepreneurial space as in access to health care. In late November, as cases across the country yet again skyrocketed to unprecedented numbers, one can infer that communities of color and Black-owned businesses were disproportionately impacted again.

The NYFR report showed that only 33% of Black employers had an existing bank relationship prior to COVID-19. The result was such that when the nationwide shutdown hit, 41% of Black-owned businesses –– more than 440,000 –– closed, unable to access the necessary economic and social capital to stay afloat amid the crisis.

For a myriad of reasons, ranging from smaller firm sizes or insufficient credit history, Black-owned firms tend not to qualify for financing and/or apply for smaller amounts than White applicants. Contemporary racial economic inequality contributes to unequal access to capital for Black entrepreneurs. In pre-COVID times, 32% of Black business owners applied for $25,000 or less in financing, as compared to 22% of White business owners. Black entrepreneurs are also more likely to be turned down completely and receive less shares of total financing sought. For example, 38% of Black entrepreneurs reported receiving none of the financing sought, and 23% reported only receiving some (1% – 50%) of the financing sought. In comparison, only 20% of White entrepreneurs received none of applied financing, while 18% received some. Forty-nine percent of White business owners received all of the financing applied for, while only 31% of Black business owners received the same.

During the PPP loan application process amidst the pandemic, the disparity in access to funding persists. Only 61% of Black-owned firms applied for loans. Only 43% of Black-owned firms which applied for PPP loans received all of the amount sought; 26% received only some amount sought, and 20% received none of the requested amount. For comparison, 79% of White-owned firms received all of the PPP funding amount sought; only 4% received none of the funding they sought. This means Black-owned firms were five times as likely than White-owned firms to receive none of the funding they sought.

This disparate and unequal access to financing has certainly been experienced during COVID-19. Based on anecdotal evidence and conversations with business owners of color, federal aid such as the $659 billion Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) and the U.S. Small Business Administration’s Emergency Injury Disaster Loan program, both funded by the CARES Act, failed to reach minority-owned businesses with the same breadth, timeliness and intention that it reached large corporations and White-owned small businesses.

In those same 30 counties hardest hit by COVID-19, only 15% to 20% of businesses received PPP loans, despite the vast sum (4.9 million) of loans approved and the relatively small average loan size ($107,000) distributed. A UnidosUS and Color of Change survey conducted in mid-May 2020 found that only 1 in 10 Black and Latino small businesses received the full amount of assistance applied for.

This, coupled with the highest concentrations of Black-owned businesses being in those sectors hit hardest by the virus and the shutdown, meant these businesses were more apt to close for good as a result of the pandemic. In fact, the five sectors hit hardest by COVID-19 shutdowns — leisure and hospitality, retail trade, transportation and utilities, construction, and other services such as personal care — represent almost 40% of total revenues for Black-owned businesses.

A second report, this one from the National Bureau of Economic Research, showed that while 17% of White-owned businesses were forced to close during the spring as a result of the shutdown, businesses owned by minority men and women closed at much higher rates –– Black, 41%; Latino, 32%; Asian, 26%; and female-owned, 36%.

Both reports also allude to pre-existing funding gaps, as does the ResilNC/NCRC report compiled this fall.

“COVID hit quick(ly); so should the funds. Access to capital has been low and even slowing in my community.”

Patrick

Local Impacts: The Commissioned Survey Data

For a more targeted glimpse at the obstacles Black business owners face, ResilNC and PIE commissioned a survey –– conducted in part by Doner, a national market research firm –– of more than 200 Black-owned businesses, which together comprise 14% of all businesses in North Carolina.

Not surprisingly, 91% of the survey respondents reported being adversely affected by the pandemic in one form or another. Some businesses were forced to pivot to new product development, implementing new methods of advertising as well as adjusted sales distribution channels. Some restructured management in an effort to cope.

I revised my business plan and let my customers know why I was making modifications to my business model.”

– Gerry

“I ramped up my online business offerings and social media marketing.”

– Ja’Net

“We pivoted, and tried to help where (we) could instead of focusing on what we couldn’t do.”

– Berinda

The results concluded that nearly 40% of respondents had to cut costs as a result of COVID-19. Close to 30% made staffing adjustments through cuts. Online search was identified as the primary means by which these business owners accessed information about program support for COVID-19, such as the PPP and EIDL programs as well as local and privately funded relief programs.

The businesses in the ResilNC survey of 200-plus Black businesses in North Carolina had gross revenues ranging from less than $100,000 to more than $10 million. Owners of the businesses, when deciding to seek capital at all, often turn to friends and family members or to web-based lenders rather than to community banks or national lending firms. Of the respondents, 89 noted that they relied on local, regional or national banks. Another 55 relied on personal credit cards or friends and/or family. Only 12 had equity investors and another 11 relied on community development or foundation grants. Only 40% paid themselves a full time salary. Despite that the overwhelming majority of these businesses were small businesses looking to expand, 80% of respondents indicated that they had not sought technical assistance services in the preceding four months and 60% of survey respondents said they were unfamiliar with the term technical assistance prior to taking the survey.

Identifying the Needs of Black-owned Businesses:

The research and practical experience explored in this report identify an array of needs of the Black Business Ecosystem that stem from a long and violent history of African American disenfranchisement.

Photo: ©Akarawut – stock.adobe.com

Filling the Gaps within the Black Business Ecosystem

Historically, White mobs would set upon thriving Black sections of towns where businesses had begun to prosper –– among the most widely known instances are Wilmington, North Carolina, in 1898, and in Tulsa, Oklahoma, in 1921. The former is the only successful coup d’état in our nation’s history. The latter is commonly referred to as Black Wall Street and is the subject of countless books and documentaries. These tragedies of the past still shape the challenges of today.

There is an ongoing cycle of asset poverty in the African American community that is manifested in the lack of an existing relationship between Black business owners and banks which continues a lack of wealth in creating further barriers to lending and financing. A lack of financial investors, asset poverty and corresponding higher fees and interest rates keep Black businesses ill prepared for economic downturns and national crises such as the COVID health and economic crisis.

With this knowledge, investors, lenders and minority business owners who have beaten the odds must coalesce to form strategic and accessible pathways for new and existing business owners to find and secure stage-based capital and other resources needed to thrive. Beyond this, there must be greater minority representation in and involvement from venture & equity capital and merger & acquisition capital, with those funds made available to growing businesses seeking to expand beyond a single location or to serve 30 clients rather than half a dozen.

Although there has been an undeniable failure on the part of major financial institutions to support and maintain Black businesses, there are local organizations and institutions which have successful track records with supporting and sustaining Black businesses in their local ecosystems. These organizations –– local Black-owned banks, CDFIs and local capital funds which operate outside the realm of major financial institutions and yet are successful in uplifting and maintaining local businesses –– need more resources to continue addressing the precarity of Black businesses nationwide. As noted by a recent NCRC paper, “Are Loan Modifications For Small Businesses a Possibility in the COVID-19 Pandemic? A Survey of Race and National Origin and Access to Small Business Loan and Modification,” it is only with credit unions and CDFIs where African Americans receive a greater portion of loan modifications than White Americans.

Black-owned banks predominantly serve the Black communities in which they are located. In 2016, among Black-owned banks, the median share of the financial institutions’ estimated service population that was Black was 62%. For comparison, the median share of the estimated service population that was Black for non-minority owned banks was only 6%. Furthermore, 33% of Black-owned banks’ mortgage originations went to Black borrowers, compared to a mere 2% of non-minority owned banks. This financial stability and investment into Black communities is also seen in the tendency of Black-owned banks to support local small businesses in greater numbers, providing much-needed financial support. Local CDFIs can also play a major role in supporting Black businesses, with their access to federal funds and focus on low-income, underserved clients.

It is incumbent upon those with the knowledge and the resources to create access to capital for minority business owners, and provide the expertise and the resources that exist for their benefit but have generationally been held at bay. It is not enough for just local Black-owned banks and CDFIs to financially sustain small Black-owned businesses. The gaps in credit among low-wealth areas and communities of color is more substantial than can be remedied by CDFIs and local banks who are often under-resourced themselves. Larger financial institutions must not only make up for historic neglect of Black communities and businesses, but significantly invest more in the entire economic ecosystem of Black businesses, neighborhoods and economic infrastructure.

Moving From The Technical Assistance Model to Trusted Advisors Model

Similar to the models common in Venture/Equity Capital Investments, the mentorship and collaboration from financial investors can be more beneficial than the technical assistance model.

A buzzword used to define limited means of mentoring and coaching business owners, “technical assistance,” must evolve and come to describe the cultivation of relationships between business owners and trusted advisors –– accountants, tax, real estate, intellectual property attorneys, etc. –– who will work in lockstep with entrepreneurs, maximizing growth and capacity potential at every turn. The technical assistance model relies on providing assistance with logistical tasks such as grant or loan applications.

Although this support may be necessary, it’s not sufficient to foster significant investment and development. Monetary investment and support is needed as well.

Throughout the pandemic, many minority business owners were forced to find experienced parties who knew how to format and fill out applications for federal relief funding –– PPP and EIDL program loans –– to overcome the disqualifying parameters that prevented their initial applications from being accepted. One reason for this is that during the early stages of development, most micro-business owners saw little instruction in finances, taxes, investment or real estate.

Berinda C’s Story

Berinda C. operates an education-based small business in Durham, North Carolina. She said her business applied for PPP loan assistance but did not receive the full amount requested. Other sources of relief proved elusive.

“We’ve had to be very creative because our business is structured differently. We applied for every grant we qualified for,” Berinda said.

Despite the proactive approach, Berinda’s business received only one grant.

Fortunately, her business was able to pivot to online instruction, as did most public school systems across the country, providing Berinda with an opportunity to remain operational.

Yet without a trusted advisor, she had to rely on the local community college Small Business Center and the SBA for guidance. While these are great resources afforded to all who seek their assistance, they do not equal the level of service or expertise found in ongoing partnerships with trusted advisors whose backgrounds –– and frankly, whose livelihoods –– are based in the delivery of expert guidance in specialized areas such as taxes or the law.

“It would have been nice to know where businesses catering strictly to education could go,” she said.

Without access to capital or a relationship with a trusted advisor versed in financial management or the legal landscape regarding stability in a national crisis such as the pandemic, Berinda and other business owners found themselves exposed and without means to prepare for or endure the subsequent shutdown.

Traci N.’s Story

Traci, the founder/sole proprietor at UNEXO, is newly married with four children. Her business focuses on helping leaders create team environments that are safe, productive and deliver results. She is four years into her endeavor after leaving corporate America where she worked for twenty years in Human Resources.

When COVID-19 impacted Traci N.’s business in Wilmington, North Carolina, she said the first phone call she made was to her accountant. She then utilized a COVID-19 support group found on Facebook.

In an example of the benefit of having a network of trusted advisors, Traci was able to successfully partake in the first round of PPP funding after she was invited by a contact in banking to participate in a pilot program setting up online applications for loan applicants.

“Having that contact and opportunity to be in the pilot was surely a blessing,” Traci said.

By connecting business owners to trusted advisors through accelerators and incubators such as those that comprise the Triad’s entrepreneurial ecosystem –– including Winston-Salem-based Winston Starts and Flywheel Co-Working, as well as in Greensboro through LaunchGreensboro and the Nussbaum Center for Entrepreneurship –– new and growing small businesses gain invaluable information while pursuing stage-based capital.

In this regard the model is not new, but is in early adoption. More investment as well as further involvement from a more broad spectrum of trusted advisors is needed and ought to be implemented in more places than just Raleigh and the Research Triangle, Durham, Charlotte and the Triad, but across the entire state of North Carolina and throughout the country.

“The community organizations that are doing the groundwork, CDFIs such as Piedmont Business Capital and Carolina Small Business Development Fund, which bring in both federal and private funding, those are the organizations on the frontlines providing capital to those communities. Yet they are underfunded,” said Talib Graves-Manns, Co-Founder of Partners in Equity.

“Imagine if these organizations were significantly invested in the way large venture capital funds are. They could have more boots on the ground, talented individuals and programs such as incubators and accelerators that could go much deeper into supporting Black and minority businesses with a more robust result,” he said.

Providing Capital Throughout a Business’ Life Cycle

While a business can begin to grow organically through early market penetration and capital raised through friends and family, to truly gain a foothold and insulate itself against external market pressures, a cushion is needed. Also, accessing resources, making key hires and operational investments are instrumental to growth, all of which require significant capital often out of reach for a Black-owned business. It is imperative to invest in small Black-owned businesses to make key steps for growth such as more hires and capital investments more attainable.

Prior to the pandemic, Black-owned employer firms constituted about 2% of the more than 5.7 million businesses with employees.[4] Black-owned employers are often younger, smaller and less profitable than White-owned firms. This difference is more pronounced for Black women business owners.

“Small, Black-owned businesses like mine compete against the entire ecosystem to recruit employees,” said Gerry M. “The market itself will out price us to offer competitive wages and benefits for most top rank(ed) employees,” he said.

Private, as well as local and federal public dollars, must pour into pre-seed and seed funds, helping business owners achieve a foothold in the market as they work to invest in their own real estate and means of production. A Crunchbase Diversity Spotlight 2020 report highlights that since 2015, Black and Latinx founders raised nearly $15 billion in seed funding, which represents only 2.4% of funding raised in that time though these communities represent about 30% of the national population.

Pre-seed funding is necessary to take a company from idea stage and proof of concept through organization and product launch. Subsequent seed funding and series rounds allow a company to gain market penetration and explore new product development while identifying new market segments, advertising and marketing strategies and expansion.

African American business owners most often start at a deficit in resources to achieve these milestones in fundraising without external assistance. Also, without trusted advisors to help navigate the pitfalls of mismanaging funds or failing to operate effectively from debt can derail a business despite its early success. Business owners must receive instruction along with the capital investments received early on to be able to capitalize on later stage growth opportunities –– private equity, M&A capital and exit or succession planning.

Addressing Community and Asset Capacity

Missing from our analysis thus far is exploring that capacity for a business owner to seize control of his or her assets to reduce risks and costs, increase production as well as profits and achieve real growth. This is particularly important in light of the disadvantage many Black-owned businesses have amid gentrification. Places like Harlem or Charlotte, North Carolina, lost significant Black-owned business over a course of a decade due to new developments and rising costs.

Business location and its racial composition have a consequential adverse impact on revenue generation. A recent Brookings report reviewing a sample of businesses across 86 zip codes describes the inequity and devaluation of businesses in predominantly Black communities, concluding that highly-rated businesses (those with four to five stars on Yelp) in majority-Black neighborhoods experience a gap in revenue growth of two percentage points when compared with highly-rated businesses in other neighborhoods. That is an annual loss in business revenue as high as $3.9 billion for Black-majority neighborhoods than businesses in non-Black neighborhoods.

This correlation between neighborhoods and revenue growth and the squeezing out of business owners due to rising market costs bring to bear the need for additional investment in African American communities so that businesses can acquire and control their own assets; as well as expand, and in some cases have greater access to a more engaged and higher income consumer base.

Continued community investments are also needed to support the growth of Black-owned businesses, particularly in predominantly low-income communities. Opportunity Zone investments are one example of a federal tax vehicle that has potential in funneling investment to communities and businesses of color, but has fallen short in living up to its designed purpose. According to the Urban Institute, the Opportunity Zone capital is flowing more in commercial and residential real estate than into businesses. Nearly 97% of the more than $10 billion raised by opportunity funds so far has been raised by funds on commercial or residential real estate.

There is still ample opportunity to leverage Opportunity Zone investments, maximizing the ROI for the investor while also catering to businesses most in need. Innovative ideas around granting eventual ownership of the property to the business owner while in the meantime fostering growth can truly allow for key hires, creating jobs and reinvesting dollars into the community, furthering revitalization efforts and safeguarding against gentrification by outside developers.

Courses of Action to Answer the Needs of Black-Owned Businesses

Photo: ©Kateryna – stock.adobe.com

What can be learned from our analysis of how businesses have fared amidst a global pandemic is that there is a disconnect between the Black business ecosystem and the traditional funding sources that support most businesses. Organizations –– traditional, Black-led and those with Black entrepreneurial focus –– are limited in their ability to meet the needs of Black-owned businesses meaningfully. Available funding pools are misaligned and not serving the greatest need. The numerous barriers to growth for Black business owners stemming from contemporary racial economic inequality, require innovative investments to comprehensively bridge the divide between the Black business ecosystem and the economic growth and community impact it is capable of.

Investment in a more responsive ecosystem must come with instruction and guidance on how to apply lessons learned in the areas of wealth management, tax and real estate law and M&A, succession and exit planning. Accumulation of wealth, land, physical and intellectual property rights and the ability to transfer them to future generations is an important path to dismantling the racist and inequitable existing business ecosystem that continues to disenfranchise African American entrepreneurship.

Significant investments to building a more responsive Black business ecosystem required to strengthen program, service and resource delivery:

- Expand investor networks through (1) convening and leveraging relationships with successful Black entrepreneurs and lenders to encourage reinvestment in Black entrepreneurial ecosystems (2) encourage the creation of public databases of Black founders.

- Create and tailor incubator and accelerator models that are culturally competent in meeting the unique needs of Black entrepreneurs.

- Have investor-led entrepreneurial training programs (e.g. entrepreneur in residence program) with life investment advisors to cultivate the next generation of Black entrepreneurs and their success.

- Connect established legal and financial firms with local coworking, incubator and small business programs focused on Black business development and encourage the provision of pro-bono services, such as legal, filing trademarks, negotiating leases, writing nondisclosure agreements, etc. – to Black entrepreneurs.

Significant funding innovation and investment to foster growth, capacity and wealth attainment in Black-owned businesses include:

- Strengthen alternative lending options by (1) increasing capacity of existing CDFIs through increased federal and private investment (2) expand and/or create new CDFIs in underserved markets.

- Strengthen supplier diversity programs as these programs infuse money into the local economy and diversify economic opportunities through tier 1 and tier 2 contracting, particularly for small/non-employer firms.

- Encourage additional capital in the form of grants for those seeking follow-on financing beyond startup capital and wish not to accrue additional debt.

- Encourage impact investment models or private corporations to pledge cash holdings and/or net income annually to support financial institutions focusing on Black communities and businesses.

- Continue and increase investment from traditional financial institutions while creating internal assessments of institutions’ financial products and operational practices that may create inaccessibility to funding for Black entrepreneurs.

- Establish pre-seed investment funds exclusively for Black entrepreneurs and, in some cases, pivot existing funds to target early stage businesses investors wouldn’t typically consider.

- Increase investment in state and local business funds at the level of larger venture capital funds.

- Reevaluate Opportunity Zone incentives to broaden the pool of investors, incentivize based on job growth and impact over profit, and encourage equity investments in local CDFIs and other community funds.

- Increase minority representation in equity and venture capital by diversifying investor and firm teams, e.g. recruitment of talent out of HBCUs and land-grant universities.

How North Carolina is Uniquely Responding

A greater emphasis is today being placed on a more DIY-centric approach to the ecosystem cultivating its own streams of investment, as well as erecting pillars such as trusted advisors in the place of technical assistance and stage-based investment in the place of offering coaching as capital to help bolster the foundation these businesses are built upon. This will allow further insulation against market downturns and external pressures faced by minority-owned businesses, already at greater risk than their non-minority counterparts.

Some of the nation’s largest banks have recently pledged millions of dollars to support minority-owned businesses and resources that aid them to better achieve these goals, as venture capital firms began to increasingly emphasize and push toward more equitable funding for the Black business ecosystem.

N.C. IDEA recently formed a 25-member Black Entrepreneurship Council in effort to supply grants and open doors for minority-owned businesses. These efforts and numerous others emerging in recent months, despite the pandemic or as a result of it, is part of the antidote for the socio-economic disenfranchisement that has inhibited Black entrepreneurship for generations.

In addition to investment funds and data research efforts such as PIE-NC and ResilNC, more and better funded accelerator and incubator programs must be implemented with a focus on strengthening Black entrepreneurship in the context of a deep and far reaching racial wealth divide cases catering to, Black.

That is where organizations such as PIE-NC and others like it must play an instrumental role in supporting these businesses. PIE-NC, for example, provides patient capital via equity investments and downpayment assistance to businesses looking to acquire new or preserve existing commercial real estate holdings. The firm accomplishes this by providing direct capital investment into commercial real estate transactions to make owner-occupied commercial real estate deals more bankable. At Opportunity Zone maturity (8-12 years), PIE works with business owners to refinance its position, making the business owner the sole-asset holder.

Despite the successes and achievements of so many brilliant, timely and pioneering business owners whose ideas have shaped the nation’s culture, infrastructure and legal landscape, there is more work to be done. The pathway toward sustainable and empowering entrepreneurship can only be built through a strong and properly invested Black business ecosystem.

Authors

Photo: ©daniilvolkov – stock.adobe.com

Dedrick Asante-Muhammad

Chief of Membership, Policy and Equity at NCRC

Dedrick Asante-Muhammad joined NCRC in January 2019 as the Chief of Race, Wealth and Community. Currently, he serves as Chief of Membership, Policy and Equity. During his tenure as Chief of Race, Wealth and Community, he oversaw NCRC’s National Training Academy, Housing Counseling Network, DC Women’s Business Center and the Racial Economic Equity Team. Dedrick is known for his racial economic inequality analysis particularly as it relates to the racial wealth divide. His knowledge and leadership has fostered growth and progress in organizations such as Prosperity Now, the NAACP, the Financial Freedom Center, Rev. Al Sharpton’s National Action Network and Institute for Policy Studies, and more.

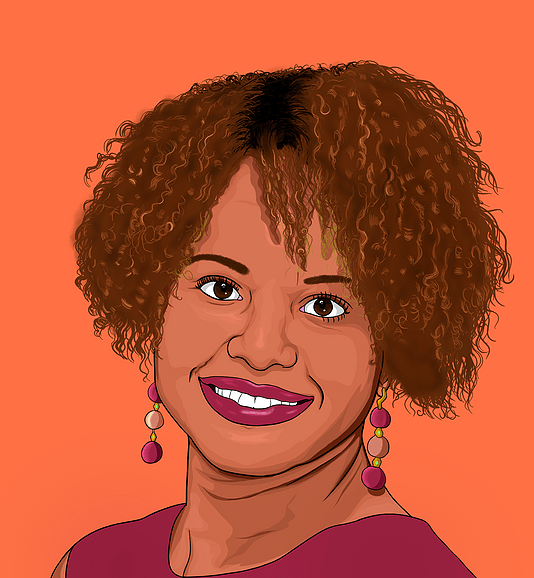

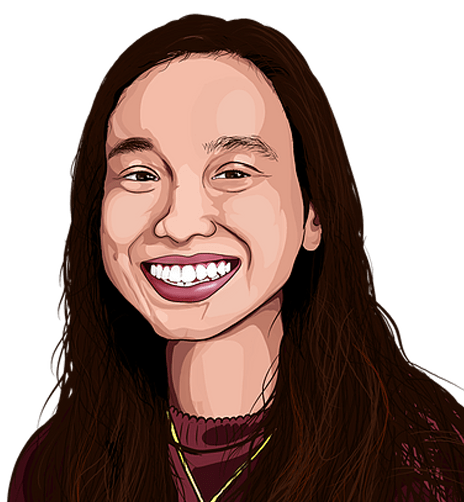

Jamie Buell

Coordinator of Racial Economic Equity at NCRC

Jamie Buell has been working with NCRC’s Race, Wealth and Community team since January 2020. A UCLA graduate with a bachelor’s degree in Sociology and Civic Engagement, Jamie multiracial upbringing melded together the differing realities of wealth and financial health among White Americans and minority groups. Her deep understanding of the history and theoretical frameworks that have allowed for the U.S.’s pervasive and disparate racial wealth divide makes her a strong advocate in racial economic justice.

Talib Graves-Manns

Co-Founder of Partners in Equity

Since 2015, Graves-Manns has served as Google Entrepreneur-in-Residence (2015-2016) and founded a CDFI-backed HBCU Entrepreneurship Center, Knox Street Studies and Black Wall Street Homecoming. Talib’s day-to-day responsibilities across his interests are varied and cross-functional, mostly centering on business strategy and driving growth. Talib subscribes to a customer-centric thesis, where voice-of-customer is paired with marketplace trends and met with innovation to deliver above-par experiences, products, and solutions.

Wilson Lester

Co-Founder of Partners in Equity NC.

Lester is an accomplished entrepreneur and leader, and is widely regarded as a community finance and economic development expert. His work centers on ensuring that access to resources and opportunity are available to everyone, particularly members of socially disadvantaged groups. Across his 20-year career, he has built and led organizations that focus on solutions that move customers and communities forward. A strong believer in the role philanthropy plays in building communities, Lester supports and serves on the boards of directors for the Nussbaum Center for Entrepreneurship, Reinvestment Partners, and Cone Health Foundation Board.

Napoleon Wallace

Co-Founder of Partners in Equity NC

Wallace is a Senior Fellow at Frontline Solutions, a Black-owned management consultancy, with more than 15 years of experience in finance and community economic development. Wallace recently served as the Deputy Secretary of the North Carolina Department of Commerce, and has served as a Social Investment Officer at the Kresge Foundation; on the executive staff at Self-Help; as the turnaround CEO for two troubled CDFIs; as an investment banker with Wells Fargo Capital Markets; and as a commercial banker with M&F Bank. Wallace is a native of rural eastern North Carolina (US), the proud son of a teacher and a small-business owner.