Columbia at 55:

Creeping Segregation and Lack of Affordable Housing Threatens A Legacy of Black/White Integration

February 1, 2023

Image: Preservation Maryland

Bruce C. Mitchell, PhD, Senior Research Analyst

Dedrick Asante-Muhammad, Chief of Organizing, Policy, and Equity

Forward

In 1974, I as a one-year-old moved to Columbia, Maryland, with my white mother and Black father from New York City. They both had seen press about this “new town” launched in 1969 where the first baby born in Columbia also came from a mixed household and was publicized as a community welcoming inter-racial households. My mother from Dothan, Alabama and father from Little Rock, Arkansas were looking for a place to raise their family, and similar to thousands of others, Columbia seemed the right place.

Growing up in Columbia during the 1970s with parents who were involved in the civil rights movements of the 1960s, I was quite aware that Columbia, particularly in regards to race, was trying to model something outside of the norm in the United States. At a very young age I understood that Columbia was a refuge from much of the more intense racism that could be easily encountered such as accidentally driving into a Klan rally in rural Maryland or not being allowed to visit my white grandfather’s home in Alabama until I was in college. Yet, as Aaron McGruder’s famous comic strip and even more famous cartoon The Boondocks infers there is still plenty of racial inequality to be found in the “post-racial” suburb (Aaron was a Columbia high school classmate of mine). It was and is still apparent in Columbia that neighborhoods with the highest concentration of African Americans are less well-off than whiter parts of town and that schools with higher levels of African Americans are considered weaker schools. As a person who grew up in Columbia, and returned 12 years ago to raise my own family – and as someone who professionally has been studying the racial wealth divide for the last 20 years – I have long been interested in examining the history of Columbia beyond my childhood memories, and scrutinizing its challenges and progress in addressing Black/white inequality.

Essential to this project was the lead writer Bruce C. Mitchell, Ph. D., a senior research analyst at NCRC. Dr. Mitchell has been an author of reports such as “Shifting Neighborhoods: Gentrification and Cultural Displacement in American cities” and “HOLC ‘Redlining’ Maps: The Persistent Structure Of Segregation and Economic Inequality”. Dr. Mitchell also has deep roots in the development and agricultural history of Howard County. Finally, we would like to thank Andy Masters, Executive Director of the Columbia Housing Center. Andy and his organization’s work to strengthen “racial and ethnic integration and diversity in Columbia” helped inspire this report. I hope that data shared in this report helps us understand the challenges and success bridging Black/white inequality and can help the nation as a whole address the deep inequality that maintains itself in this 21st century.

Dedrick Asante-Muhammad

Chief of Organizing, Policy and Equity at NCRC

Introduction

Columbia is an opportunity for the growth of America to change course away from needless waste of the land, sprawl, disorder, congestion and mounting taxes to a direction of order, beauty, financial stability and sincere concern for the growth of all people.

James Rouse, 1964

In 1963, Columbia existed only as an idea. It was to be a “new town” set on 14,000 acres of land in the center of Howard County, Maryland. The concept of “new towns” was born in the United Kingdom during the post-war period, though similar ideas in the United States had been embraced by the federal government during the New Deal, resulting in the construction of communities like Greenbelt, Maryland. Following some of the principles of these earlier “green belt cities,” “new towns” were to be an antidote to the overcrowded, polluted conditions in cities, which were a result of poor planning and inadequate land-use restrictions as cities industrialized. Howard County was mostly rural farmland, and the planning of Columbia entailed land development patterns distinct from those that shaped post-war suburban developments. Columbia represented a new method of rural/urban development, the goals of which were set out in a presentation to officials representing the people of Howard County. These goals emphasized the benefits of development to the county and included:

- No additional tax burden to residents of Howard County

- Respect for the land, with preservation of natural amenities and open spaces

- A complete and balanced community, which provided a broad range of opportunities for housing, employment, with cultural and recreational facilities

- Highest possible standards of beauty, safety and convenience with strict control of signs, commercial areas, architecture and landscaping

- Provision of all major utilities and services without additional cost to the County

- Provision of the best possible environment for the growth of people

Implicit to the third goal of building a complete and balanced community, James Rouse, who was the developer, stated that “Like any real city of 100,000, Columbia will be economically diverse, polycultural, multi-faith and inter-racial.” But the formal goals presented to Howard County residents in fact went further than Rouse’s vision of a “new town” that would have the diversity he regarded as de-facto for “any real city.” The sixth goal established the highest possible aspirations for Columbia as a community fostering the “growth of people.” Columbia was imagined as a “clean-slate” project in contrast to the dirty, fixed reality of existing cities.

The idealism inherent to Rouse’s conception of Columbia is evident when it is compared with the practices that existed in 1960. The development strategy, marketing and sales practices of the builders selling units in Columbia contrasted with those of earlier developers of planned communities, such as the prominent firm Levitt & Sons. “Levittowns,” as the company’s towns were known, were built on massive scales, following a cookie-cutter approach to suburban development. Costs were minimized by standardized production techniques in order to provide affordable housing which relied on VA and FHA financing. But the affordable housing of Levittown was available to “Whites only.” Property sales in Levittowns were restricted by racial covenants — since-banned rules about who could and could not buy and sell homes. The FHA and VA favored mortgage lending in these covenant-restricted communities under the federal government’s own racist housing policies of the time.

Columbia had no racial covenants and there was no racial steering of buyers. It developed housing which was affordable across a range of incomes. Columbia was designed and developed during the 1960s, when the civil rights movement was making progress. However, the Federal Housing Act of 1968 had yet to be passed when the community was conceived. Columbia and the community of Reston, Virginia, represented case studies in a new era of desegregation for American housing in the 1960s. These efforts at desegregation focused on easing the division of Black and White residential neighborhoods. While there has been exponential growth of the Asian and Hispanic communities of Columbia during the past three decades, this report focuses on the economic status of the Black community since development.

The Development of Columbia

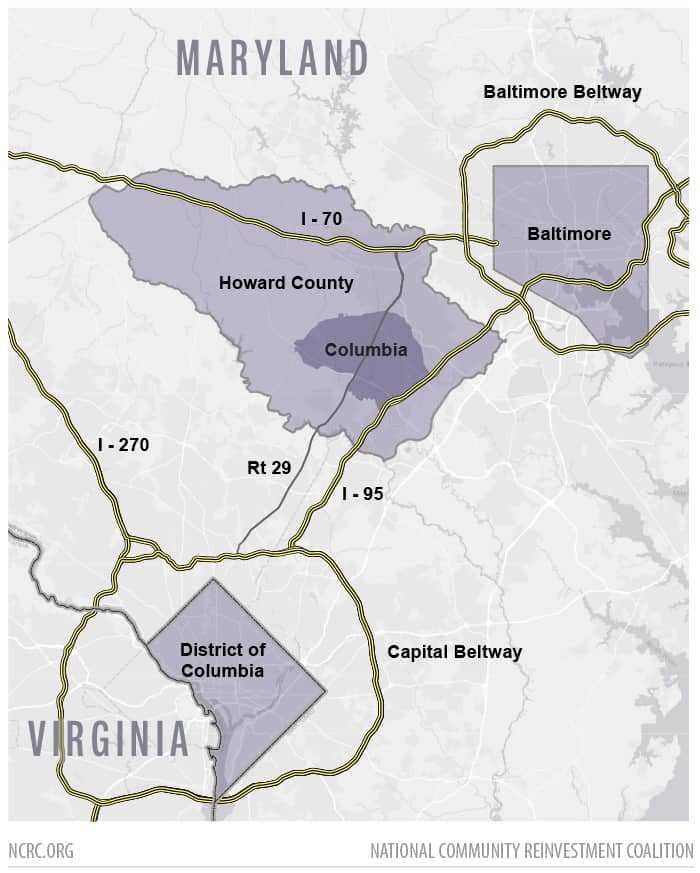

In 1960, the county seat of Ellicott City was the only urbanized portion of Howard County. Some suburban development had started in the mid-1950s in the area north of Ellicott City around Normandy Plaza and at Allview Estates on the Columbia Pike/Route 29 corridor. The remainder of the county consisted of agricultural land. It was a striking rural setting, dotted with large tracts of orchards and farms. However, the county is sited between Washington and Baltimore, and is bisected by major transportation routes: Interstate 95 and Route 29 running north-south, and Interstate 70 running east-west (Figure 1). These factors favored development, and the Rouse Corporation envisioned Columbia as the new center of population growth in the county.

Figure 1: Columbia, Maryland’s location between Baltimore and Washington

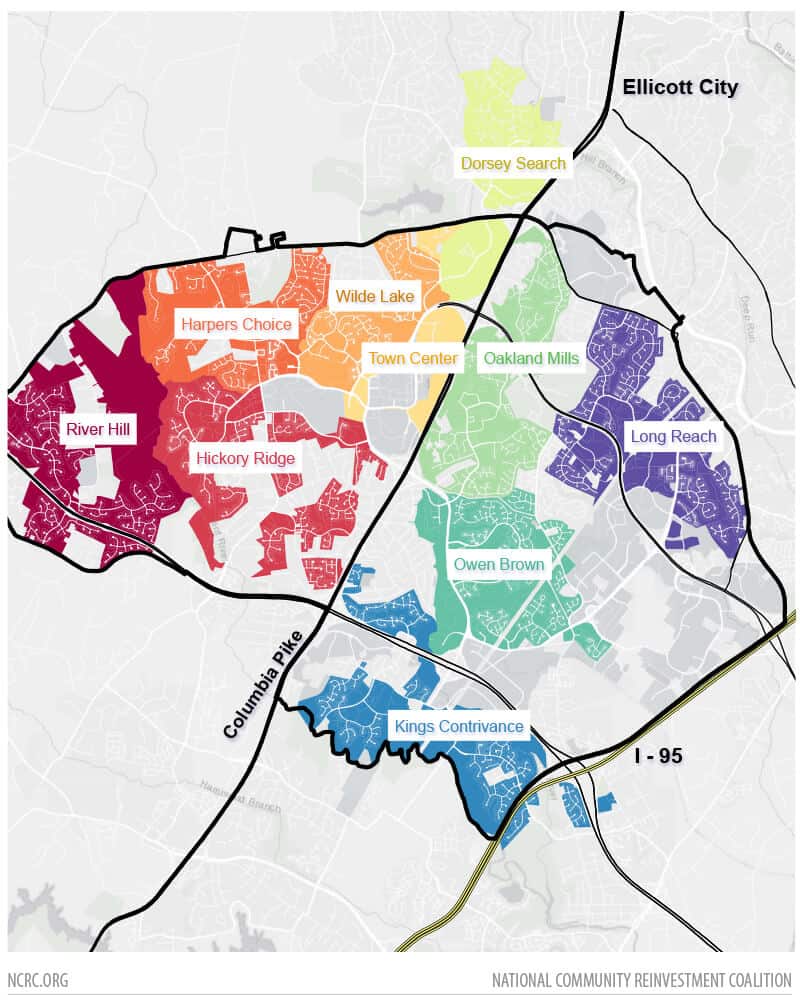

Columbia was planned by a team with expertise in many different fields: urban planning, economics, real estate development, mortgage lending, education, health and recreation. Their goal was not just to build housing, but to create a community. A central part of the design of Columbia was the construction of clusters of housing organized into village centers (Hoppenfeld, 1967). The village centers were envisioned as providing a range of services within a short distance of their residents: schools, shopping, libraries and recreation (Figure 2). The Mall at Columbia and nearby Town Center were the first areas developed, followed by five villages between about 1966 and 1972: Harper’s Choice, Long Reach, Oakland Mills, Owen Brown and Wilde Lake. These villages conformed closely with Rouse’s original design goals. Developers built considerable mixed housing (rental apartments, townhouses and single family homes) in these areas. The remaining four villages of Hickory Ridge (1974), King’s Contrivance (1977), Dorsey Search (1980), and River Hill (1990) did not adhere as closely to Rouse’s vision. The last village of River Hill is both the most isolated from the Town Center, and the most exclusive. The largest proportion of single-family homes were sited in River Hill during its development, consequently, it has the highest median household income and median home values (See appendix tables A-1 and A-2).

Figure 2: Columbia Maryland’s ten villages

Population Change

Once established, Columbia rapidly increased the development of Howard County. Population quadrupled from 1960 to 1980, by which time nearly half of the county’s residents lived there (Figure 3). Since 1980, development of the areas adjacent to Columbia has reduced its share of the population, so that it was about a third of the county total in 2020.

Figure 3

Howard County African American Population

Planning and construction of Columbia took place during the era of immense change to the US urban system. First, a national-level demographic shift was underway as Whites moved from central city neighborhoods to surrounding suburban areas in a pattern characterized as “white-flight”. Some 841,000 Whites moved out of central cities each year from 1964 to 1969 on net. Over the same period, Black Americans moved in: Those cities saw a net Black in-migration of 60,000 per year as Whites left. Meanwhile, surrounding suburbs were attracting an annual net in-migration of 1,069,000 Whites and 34,000 Blacks. The intensity of this outflow acted to consolidate patterns of racial segregation in central cities where the Black population increased from 12.3% in 1950 to 21.1% by 1969.

At the same time these demographic trends were intensifying, the federal government also expanded civil rights for Black Americans. The Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Fair Housing Act of 1968 created legal structures to enforce more equal treatment and to promote desegregation in American life. Lawmakers banned practices which had restricted where Black people could live, like redlining and residential steering. Columbia was developed as an integrated community not before or after these social changes, but during them. This was exceptional: a contemporary survey of 40 planned communities found that Columbia was one of just two to embrace integration as a goal. (Becker, 1970) The goal of racial and socioeconomic balance was part of the core mission of Columbia’s developers. It represented a fresh alternative to the patterns of segregated suburbanization that had been unfolding nationally.

Figure 4a

Figure 4b

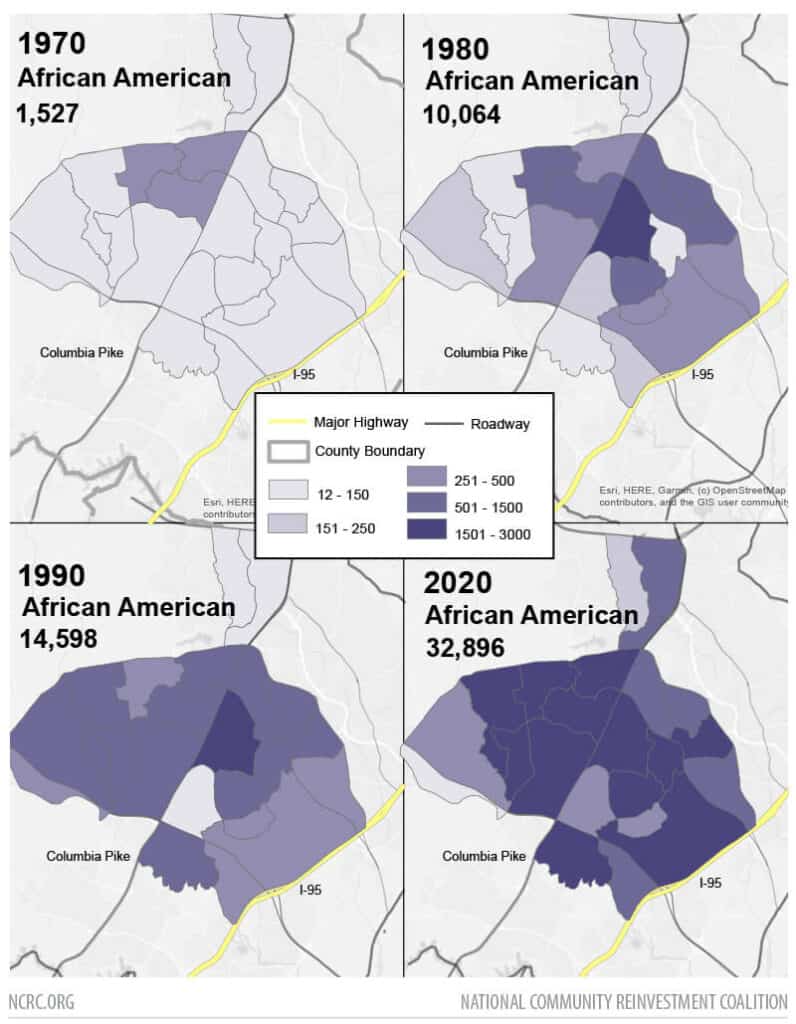

The Black population of Howard County increased rapidly from 1970 to 1980 (Figure 4a). Much of this increase occurred in Columbia. In 1970 the Black population was 1,527 expanding to 10,064 in 1980 (Figure 5), or from 8.6% to 18.1% of Columbia’s residents (Figure 4b). The Black population increased steadily after that, such that Howard County was 21.4% Black and Columbia 28.1% Black as of 2020. This corresponds with an overall increase in diversity, so that today, approximately half of Howard County’s population identifies as having an ethnic or racial minority background.

Figure 5: Changes in the distribution of Black population in Columbia 1970-2020 (Source: LTDB based on US Decennial Census)

White Population Decrease & Demographic Change

The American population in general is becoming older and more diverse, according to data gathered over the last two census periods. These broad trends are acutely notable in the Baltimore-Columbia-Towson metropolitan area. The area’s median age and percentage of older residents have increased since 2006 while the share of White non-Hispanic residents has fallen. In addition, overall population growth slowed in the metro area, with outright decreases in the population of the City of Baltimore. In Columbia, population growth slowed but did not stop during the period. Between 2000 and 2020, Columbia and Howard County became more diverse and older. First, the percentage of White residents decreased from 57% in 2000, to 42% in 2020 (Figures 6a & 6b). The percentage of Asian, Hispanic and multiracial residents has doubled or tripled, while the Black population increased from 19% to 26%.

Figure 6a

Figure 6b

While there has been an increase in diversity in Columbia, it has also been marked by elevating measures of segregation. Both the proportion of White residents and their number has declined – 11,596 over two decades (Table 1). This mirrors national and state trends, with the White population of Maryland dropping 244,176 in the last decade. Simultaneously the population is aging at national, state and town levels. In Columbia over the decades since 2000, the percentage of residents of all races age 65 and older doubled, from 7% to almost 16%, while the percentage of children went down from 26% to 21%. The aging of the residential population is seen in both Black and White racial groups.

Table 1

How has this played out in Columbia’s different villages? Table 2 summarizes changes in the White population at the census tract level across the different villages, first for older residents, then by overall percent and count. Seventeen of the 19 census tracts in Columbia have seen increases in the percentage of White residents 65 years of age and over, with the same amount of tracts experiencing declines in the totals number. In all, there has been a decline of nearly 15,000 White residents in Columbia over two decades. Nearly all of the villages experienced a loss of between 800 and 2,600, except in River Hill where there are now about 500 fewer White residents. It is surprising that these population shifts are so similar across Columbia’s villages, both the older and the newer ones. Whatever is driving these changes is not so simple as an “aging-out” of the older White residential population in the original villages.

Table 2

Segregation

Columbia’s planners initially succeeded in fostering an uncommonly integrated community. In 1980, Columbia had impressively low levels of segregation with an evenly distributed Black/White population that had a high degree of exposure to one another on a neighborhood level (Table 3).

These measures gradually worsened, however, even as the two closest metro areas of Baltimore and Washington managed to somewhat reduce their appalling levels of segregation over the same decades. In Columbia, meanwhile, three common measures of segregation at the community level all showed worrying trends: The evenness of distribution of the Black population and the exposure of Black and White groups to one another both declined, while Black isolation from Whites increased. What could explain this?

First, the percentage of the non-White population of Columbia has greatly increased so that by 2020, just over half of the residents identify as non-Hispanic White. The Black population count has tripled since 1980, with an even greater increase in the Black share of the Columbia population (from 8.6% in 1980 to 28.1% in 2020). Additionally, the homeownership rates of Black residents are lower than the average of all groups in Columbia. For instance, 76.5% of White residents own a home compared to only 52% of Black residents. Black residents therefore have a greater likelihood of living in multi-family rental buildings, which acts to cluster their population in census tracts with higher proportions of apartments (Appendix A-2) and weaken Columbia’s previously impressive integration measures.

While the Black population of Columbia is less evenly distributed relative to the White population and isolation has increased, the exposure of Black and White people to each other has deteriorated more drastically than the other two integration metrics. Exposure is a measure of the level of potential contact between minorities and the majority group in the places where they live. In the case of Columbia, there have been diminishing levels of exposure for Black and White residents, indicating that the groups are less likely to interact with each other than they were four decades ago. This intensifying pattern of segregation was identified for Howard County as a whole and for Columbia in particular over 20 years ago. A 2011 Analysis of Impediments to Fair Housing Choice cites village design as a key factor in creeping economic and racial segregation of Columbia. Older villages adhered to Rouses’ principles of economic and racial integration. Consequently, Harper’s Choice, Owen Brown, Wilde Lake, Oakland Mills and Long Reach were developed with greater concentrations of affordable housing. River Hill was not developed until the 1990s and contains few multifamily units and virtually no affordable housing. This has injected disparities between the aging villages of Columbia and newer developed areas.

Table 3

School Segregation

The economic and racial disparities at the village level in Columbia are evident in the schools serving those neighborhoods (Table 4). Three Columbia high schools – Long Reach, Oakland Mills and Wilde Lake – have majority-minority student bodies where about 60% of students are Black or Latino. A third of the students at those schools receive free or reduced-price lunch. In contrast, less than 10% of students qualify for subsidized meals at Atholton, Centennial, Howard and River Hill High Schools – where Black and Latino students account for between 15 and 35 percent of attendees. The need for subsidized lunches increased in Columbia’s high schools over the past 15 years, indicating economic shifts. The increasing economic and racial disparities prompted the Howard County School system to propose a redistricting plan in 2019 which was controversial. A modified plan was approved by the Board of Education, impacting about 5,400 students countywide. The opening of a thirteenth high school in 2023 has reignited the conversation about school redistricting. The data presented does not reflect these recent and pending changes in high school demographics.

Table 4

Income

With its proximity to the DC metro area, Howard County experiences the positive spillover effects of the economic dynamism of the region. Fort Meade and the National Security Agency are major, high-income generating employers located on Columbia’s doorstep. As a consequence of this and the ability of Columbia to attract employers in educational, professional and technical services, the median incomes of both the town and the county far exceed the national figures (Figure 7), for both Blacks and Whites. In earlier decades, median household income in Columbia exceeded that of Howard County, but as the rural character of the overall area shifted to a suburban one, this gap has closed to near parity. Corresponding with the higher levels of income found in Columbia and Howard County there has been a low level of very low income residents: In 2000 Columbia’s poverty rate was 5.4%, less than half the national rate. But by 2020, Columbia’s poverty rate increased to 7.6%, nearer the national poverty rate of 11.5%. In Howard County, the share of households enrolled in the federal Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) grew from 1% to 5.4% over the same two decades – compared to a SNAP participation rate of 13% nationwide.

Figure 7

The median income of Black households in Columbia has lagged that of all households, but the gap closed somewhat between 2010 and 2020 (Figure 8). Though African Americans in Columbia have less income than other racial/ethnic groups, Columbia’s median Black income is much higher than national Black median household income.

Figure 8

Home Value and Homeownership

During its first two decades, home values and levels of homeownership in Columbia were higher than those in the surrounding county were. That changed after 1990: Columbia achieved build-out, and construction shifted to adjacent areas in the county. Since 1990, the median home value in Columbia has been 88%-92% of that in the overall county (Figure 9). This probably reflects both the aging of Columbia’s housing stock and the greater focus on single family homes in other, more suburban areas of the county. Shifts within the building industry toward the construction of more expensive homes for higher-income households may also play a role. While home values have declined relative to the county, housing affordability has been an ongoing issue. Columbia’s stated goal of having a range of housing opportunities for different income levels has segmented the villages of the community into areas of high income/high ownership and lower income/high rental – even though Columbia incomes still compare favorably to the national median.

Figure 9

An example of the differences in the proportion of rentals to owner-occupied housing is apparent when considering two of the oldest villages, Town Center and Wilde Lake, where 76% and 57% of the households rented in the 2016-2020 timeframe. Additionally, Wilde Lake had the lowest household income, $90,411, compared to $129,516 for Columbia as a whole in 2016-2020 (Appendix A-2). In contrast, two of the newest villages Dorsey Search and River Hill are only 22% and 9% renter households respectively, and have much higher household incomes. Despite this, Columbia remains more affordable relative to local median income when purchasing a home than other parts of Howard County. The Housing Affordability Index, which factors in household income and housing sale prices, indicates that Columbia is second only to Baltimore City and Baltimore County in home purchase affordability (Table 5). The District of Columbia, Prince Georges’ County and Montgomery County have much lower levels of home purchasing affordability by this metric, meaning that relative to the local median incomes homeownership is more unaffordable.

Recently there have been plans to change and modernize Columbia’s aging Town Center, similar to efforts being made in Reston, Virginia. The proposal to rejuvenate the area through a ”Downtown Columbia Plan” includes provisions to increase the availability of affordable housing. Yet with goals of only 12% to 15% of housing to be “affordable” relative to the higher incomes of Howard County, it seems unlikely the plan will make significant progress on intensifying affordability problems and spiraling rents.

Table 5

Figure 10a

Figure 10b

Columbia has long had lower rates of homeownership than those of the county as a whole (Figures 10a & 10b). This is partly due to its higher density of rental units: The city’s planners were serious about their affordable housing goals and built an unusually high percentage of multifamily rentals as a result.

Conclusion

Columbia is a bold experiment, driven by a vision of more equitable urban development. But communities do not exist in isolation from broader social forces surrounding them. Columbia enacted a set of “best practices” in land development and community social development on a grand scale. Has it been successful?

If the Rouse Corporation’s stated goals are the rubric, then Columbia is a qualified success. Columbia was the major center of population growth, greatly expanding the tax base of the county. It certainly provided planning in the development of the land, though the rural character of Howard County was severely altered. In terms of creating a balanced community, Columbia does provide a range of housing opportunities, though perhaps differently from what James Rouse would have envisioned. It is “affordable” when taken in context with the higher income levels in the community, yet only a small percentage of its housing stock is affordable when compared to the overall Baltimore metro area. With median income at $127,545 and median home value of $409,000, Columbia is a high income enclave relative to the country as a whole. This is also true for African Americans in Columbia. African Americans in Columbia have over twice the household income of African Americans nationally. In fact, most neighborhoods of Columbia are in the top ranks of Black household income nationally, coming in at or above the 80th percentile.

Columbia was a regional leader in creating a community of Black/White integration. Though Columbia has always been a place with substantially higher median income than the country as a whole, it still was able to become a regional leader in Black/White integration and internal economic equity. Yet as time passed – and the radical upheavals in law and society that surrounded Columbia’s founding in 1967 settled into a new social and economic equilibrium – things look less rosy. While the first villages built in Columbia broke barriers, those erected in more modern times have failed to sustain the mix of rentals, townhomes and single-family homes that made Columbia a pocket of remarkable integration in a society still deeply struggling with racial inequality.

The founding of Columbia in 1967 was in many ways a preemptive response to the 1968 national Kerner Commission Report that stated “Our nation is moving towards two societies, one black, one White, separate and unequal.” Over its first decade, Columbia seemed a potential roadmap out of the crisis that the commission identified.

Yet for much of the last 10 years Columbia has failed to maintain its legacy. The 2011 analysis by Mullin and Lonergan Associates that warned of growing segregation did not prompt effective policy responses to restore Columbia’s previous leadership on these issues.

As shown by our Columbia village analysis and reflected in the demographics of high schools in Columbia, the last two villages to be constructed in the community – Dorseys Search and River Hill – have hurt Columbia in terms of Black/White integration and economic equity. Only in those newer-built neighborhoods do we see single digit African American population shares.In most others, we see 20% to 35% African American population statistics. The newest villages stand decidedly apart in economic metrics as well as representational ones: The median home value in River Hill is over $700,000 – a far cry from affordable, even relative to the high incomes of Columbia residents. The widespread homeownership opportunities Columbia was built to provide are at risk of becoming a quaint mid 20th century memory.

And what of that last, most vaguely ambitious goal of Rouse’s original planners: Has Columbia been the best possible environment for the growth of people? By many standards – income, health, education and crime – Columbia has been a successful social experiment. However, it has failed to meet the Developer’s original vision in its later villages, and is experiencing creeping segregation as the Black and White communities become increasingly clustered. Additionally, Columbia is no longer defying nationwide trends on one key measure of opportunity, but rather mirroring them: Housing affordability is declining, just as it has across American society over the past 40 years. These are troubling trends which require a rethinking of policy at the local level and even at the federal level.

A central lesson of Columbia is that even racially progressive policies at the early stages of community development – and in the marketing of Columbia as an idea and a development opportunity – have not compensated for the focus on higher income residential development and later decisions disfavoring the construction of multifamily and more affordable rentals. The increasing segregation of Columbia’s villages and of its school system were identified as trends over 20 years ago, yet policy measures to counteract it have not been effective. The vision of an economically and racially integrated new town requires a re-embrace of the vision of its founding. Columbia’s modern leaders must rediscover their predecessors’ dedication to middle income affordability and be even bolder with lower income affordability so that Columbia really can once again be an example for the entire country in diversity and opportunity.

A Message From The Columbia Housing Center On Its Work To Advance An Affordable And Integrated Columbia

There is an effort in Columbia to take aim at stemming the tide of segregation. The Columbia Housing Center (CHC) is a nonprofit organization with a mission to champion and sustain thriving, racially integrated communities throughout Columbia. Modeled after the Oak Park Regional Housing Center, CHC works to connect prospective renters with available apartments that meet their needs, are reasonably affordable to the client, and, importantly, promote the racial integration that is core to Columbia’s community values.

CHC was founded in 2017 as a volunteer Board of Directors that included residents and stakeholders who had a key connection to Columbia: They believed that Columbia could be a better, more integrated community. It was in 2020 and 2021, when the Howard County Department of Housing and Community Development invested Community Development Block Grant funding into CHC, that the organization began to take off. Hiring its founding executive director in 2021, the organization launched its rental referral service in April 2022. Additional support has come from The Horizon Foundation and residents who align with the mission and share the belief of the Board of Directors.

In the first 6 months, Columbia Housing Center has worked to connect renters with housing options that align with the mission of the organization. More than that, CHC staff works to understand the additional needs of clients and has built a network of referral sources to provide additional opportunities to support these families. As CHC grows and expands, the potential impact on Columbia’s racial integration is incredible. Oak Park’s experience shows that an organization like this one can preserve integration and promote the positive values that James Rouse kept in the forefront of Columbia in those early years.

Andrew Masters

Executive Director of Columbia Housing Center

Appendix

A-1 Census tracts associated with Columbia villages data concerning people, income and eEducation (Source: US Census Decennial 2020 and ACS 2016-2020)

View here

A-2 Census tracts associated with Columbia villages data on housing, homeownership and rentals (Source: US Census ACS 2016-2020)

View here