Earlier this year, the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) proposed a new rule to change the affirmatively furthering fair housing (AFFH) rule of the Fair Housing Act (FHA). This new proposal aims to set back years of progress by no longer enforcing meaningful community participation in the AFFH process. Without the crucial input of local community members who face housing inequalities, the new rule eliminates the main elements of accountability meant to address discrimination and inequality.

Many civil rights groups are commenting on this proposal, but they have been exclaiming disapproval for drastically changing AFFH since 2018 when three organizations sued HUD over suspension of the 2015 rule. Texas Appleseed, Texas Low Income Housing Information Service and the National Fair Housing Alliance (NFHA) asked the federal court to order HUD to reinstate the AFFH requirement. They argued that “The [AFFH] Rule’s required Assessment of Fair Housing (AFH) is an in-depth, holistic planning process that leverages data and robust community participation to inform the selection and prioritization of measures to overcome entrenched barriers to housing discrimination, residential integrations, and access to opportunity.”

The National Low Income Housing Coalition reported that this new proposal for AFFH is a fundamental misunderstanding of the Fair Housing Act and its obligations, notably by removing the AFH mentioned in the 2018 case against HUD. They said this “proposal would allow communities to ignore the essential racial desegregation obligations of fair housing law and is the latest of Secretary Carson’s attempts to weaken and disrupt HUD’s fair housing duties.”

Madison Sloan, director of Texas Appleseed’s Disaster Recovery & Fair Housing Project, told NCRC why AFFH has been so crucial to Texas and what is at stake if the new proposals go through. She says having a broad view of AFFH is essential and that fair housing is more than just about ending discrimination. Ultimately, it is about finding and addressing root causes while getting community leaders involved in the solutions.

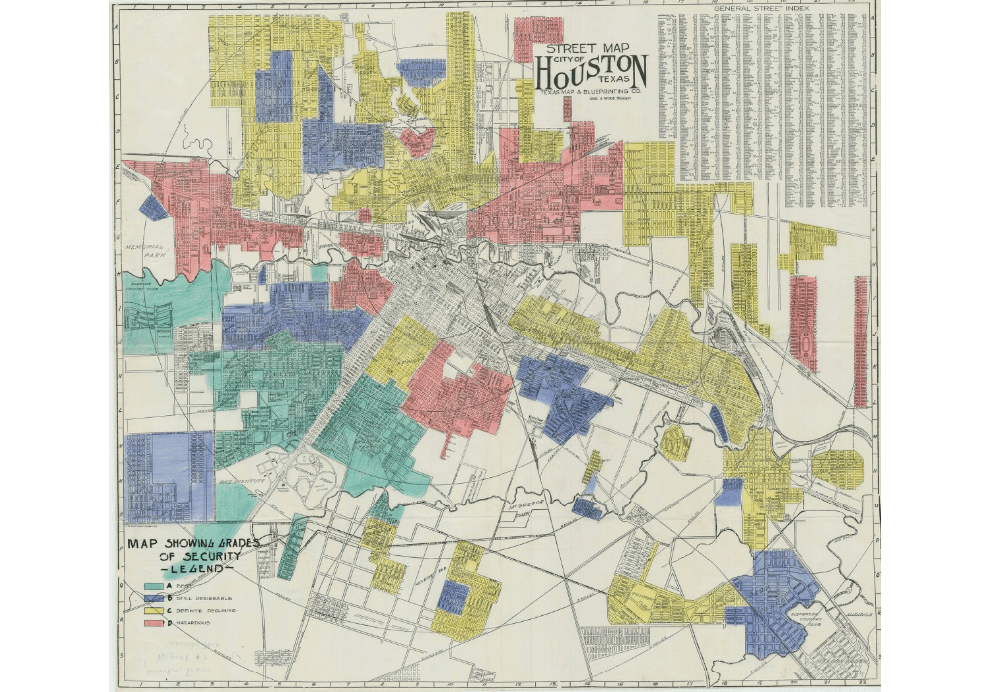

Texas Appleseed interacts with AFFH related issues regularly, as they consistently work on issues rooted in segregation and concentrated disadvantage within their community. Sloan explained that they compared the 1934 HOLC redlining maps for the biggest cities in Texas to the mapped data from multiple Appleseed projects, including Criminal and Juvenile Justice, Fair Financial Services, School-to-Prison Pipeline and Fair Housing in those same cities. Those redlined neighborhoods from 1934 are still racially segregated and are higher-poverty neighborhoods in Texas today. Those same communities also have the highest concentrations of payday lenders, high levels of arrest for juvenile curfew violations, the highest concentrations of subsidized housing, school discipline that disproportionately affects children of color and police that were more likely to use their discretion to arrest and jail residents instead of ticketing them.

“There’s an overwhelming body of research showing that where you live determines your life outcomes, from educational achievement to life expectancy. Dismantling segregation is critical to address all of the core systemic issues Texas Appleseed works on; we can’t treat the symptoms without treating the disease,” Sloan said.

Part of treating the disease is recognizing how important the 2015 AFFH rule was to low- and moderate-income communities, she added.

“It reaffirms that AFFH is not just about affordable housing or what a city is doing with its CDBG [Community Development Block Grant] funds; it’s about remedying historical disinvestment that resulted in racially concentrated areas of poverty and making sure all communities are inclusive and have equitable access to opportunity.” Sloan expressed concerns that jurisdictions may see the proposed pullback as a green light to continue ignoring fair housing requirements.

Conversely, HUD Secretary Dr. Ben Carson has publicly criticized the 2015 AFFH rule saying that it created “burdensome obligations and cookie-cutter solutions.” Sloan disagreed.

“The entire point of the rule was to help communities conduct an individualized assessment that looked at their unique histories and contexts so that they could identify the solutions that worked best for that particular community. The AFH was the kind of evaluation of barriers to fair housing choice that jurisdictions were supposed to have been conducting since 1968; the fact that people hadn’t been complying with the law doesn’t make compliance ‘unduly burdensome,’ Sloan said.

Since FHA hadn’t properly been enforced, “there was always going to be a learning curve,” she added.

“We’ve had decades of pretending that housing segregation is just a choice people make and that it’s perfectly fine to use public money to discriminate, but that’s not true. Governments and PHAs have deliberately segregated families into unsafe, high-poverty neighborhoods, artificially depressed their home values, destroyed their infrastructure through neglect and forced communities of color into geographically vulnerable and environmentally high-risk areas with discriminatory zoning.

“If those governments and PHAs find doing some research and conducting a meaningful planning process ‘burdensome,’ perhaps they should talk to some of the families in the 5th Ward of Houston whose loved ones are dying of cancer caused by exposure to creosote, or some of the children who go to mold-infested schools or schools with no heat, or some of the families who lost everything in the 2008 financial crises when their neighborhoods were targeted for predatory lending because they were Black or Latinx, about the burdens they’ve been forced to carry by segregation.”

The 2015 AFFH Rule required meaningful community participation in the fair housing planning process and was critical because that was a piece that had been missing from previous fair housing planning.

“Meaningful community participation requires affirmative efforts to reach out to the communities most affected and classes of people protected by the Fair Housing Act,” Sloan said. “Who can come to a public hearing at 10 am if they have to work, or at 6 pm if they don’t have childcare or transportation? How is notice reaching people with disabilities or people with limited English proficiency? Why should certain communities trust a government entity that has dismissed their concerns for decades?”

To affirmatively further fair housing, it requires the voices and ideas from the people that are on the ground and affected most by how a lack of regulation can put vulnerable populations at risk.

The newly proposed rule, which closes to comments on March 16th, fundamentally changes the requirements that were established in the 2015 rule. It allows jurisdictions to collect HUD money without any meaningful evaluation on what they are doing to effectively address racism, segregation or inequality in their community. The Fair Housing requirements implemented in 2015 were just starting to show positive impacts on communities, and this rule proposal could set back years of progress. It puts homeowners and vulnerable populations at risk instead of adding or maintaining protections that give them an avenue to make change.

Sara Oros is NCRC’s program coordinator for Fair Housing/Fair Lending.

Photo from Rice Digital Scholarship Archive.

*Comments on the proposed rule are due by Monday, March 16. Submit your comment at regulations.gov.