Glenn Burleigh is the Community Engagement Specialist at the Metropolitan St. Louis Equal Housing & Opportunity Council (EHOC)

This is one in a series of essays accompanying NCRC’s 2020 analysis that showed more chronic disease and greater risks from COVID-19 in formerly redlined communities. The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views or policy positions of NCRC.

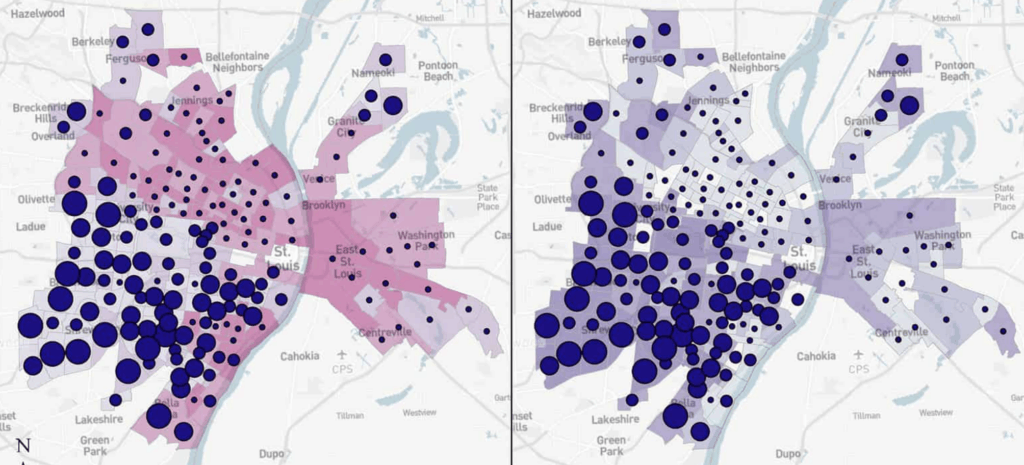

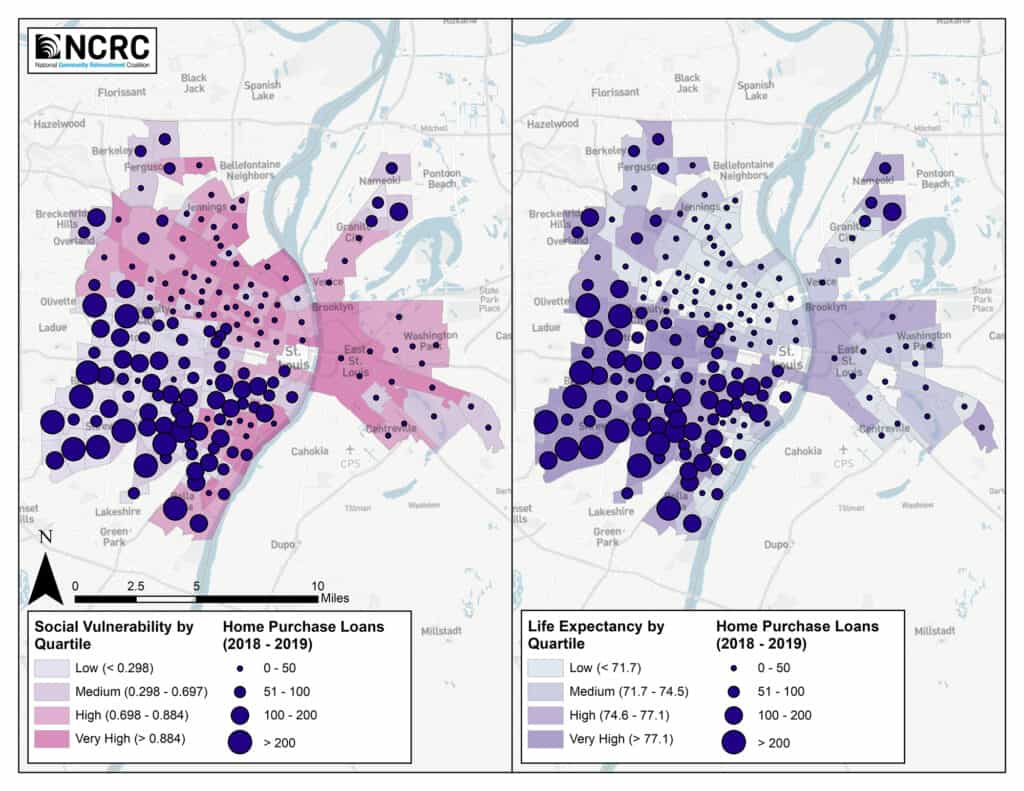

As the COVID-19 crisis unfolded in St. Louis, the maps of the infections looked very familiar to those of us who work to promote integrated and inclusive communities. Unsurprisingly, it was having a greater toll on the city’s majority-Black neighborhoods, where maps already showed elevated rates of asthma and lead poisoning. These are obviously health issues that could make the virus more lethal. The infection maps also followed other maps, but not ones that would seem to be connected at first glance — ones showing low to non-existent residential mortgage activity. For advocates that work to expand equitable capital access and an end to modern day redlining, it wasn’t surprising, as we have long been acutely aware of the connections between health and housing.

We also knew that the conditions that made these racial disparities in COVID-19 infection and death rates possible were part of a pattern that goes back to the Home Ownership Loan Corporation (HOLC) redlining maps and decades of federal, state and local policies meant to enforce segregation. These maps cemented patterns of racial segregation and disparities in capital access that are still with us, almost a hundred years later. While the COVID-19 pandemic has brought this connection between race, housing and health outcomes into greater focus, this crisis at the nexus of housing and health has been festering for many decades and has already been impacting our region’s communities of color for many generations. As the Segregation in St. Louis: Dismantling The Divide report chronicled, the active promotion of residential segregation is deeply ingrained in our city’s history.

The lack of home mortgage financing provides an underpinning for environmental racism and health disparities that aren’t limited just to those who live closer to polluting industries. It is also tied to growing up with poor indoor air quality, as the housing stock in our region’s majority-Black neighborhoods are unsurprisingly located in areas without real lending activity. This means that families can’t access home equity to keep up with the kind of regular maintenance necessary to provide safe and healthy air inside their households. Access to capital for maintenance is a necessary part of long-term, successful homeownership, yet this basic part of the housing financing is largely unavailable to significant portions of the metropolitan area. This means that even with identical credit scores and income, homeowners in majority-Black neighborhoods are denied access to an essential part of the financial system that our nation has developed to retain value in real estate assets. This dooms whole neighborhoods to decay and all of the negative impacts on quality of life that come with living in neighborhoods filled with vacant, crumbling buildings. It also means that many renters live in substandard conditions, as their units are owned by landlords who buy properties at the discount made available to them via this cash-only market. These landlords tend to make the absolute minimum investment necessary to pass occupancy inspections, leaving mold and other indoor air quality issues untreated. To add insult to injury, if many of the tenants were able to access home purchase and rehab financing, they would end up paying less on their monthly housing bills, while simultaneously building equity. These inequities in capital access, based on the complexion of neighborhood residents, have essentially predetermined that this isn’t an option for those who wish to live in the city’s majority-Black neighborhoods. Already the daily reality in these St. Louis neighborhoods prior to COVID-19’s emergence, now these same families face even greater danger as these pre-existing socially-determined conditions have left them further vulnerable.

All of this puts the need for any “new normal” to include changes to housing policies (and how our economy is structured) in stark relief. If we’re to have a #JustEconomy, then we will need to take this opportunity to reimagine how these systems work. If we don’t fundamentally change how housing and capital access are distributed, then we face an America that comes out of this crisis more segregated and with levels of inequality that exceed already historic pre-COVID highs. If we are to create a healthier society, both physically and financially, then we will need to take a hard look at the lessons of this period and take intentional steps to create a “new normal” that doesn’t recreate the racial inequities of the “old normal.”

If we are to approach recovery with an eye towards building a more racially equitable nation, then it is necessary to center these lessons. The price that thousands of families are now paying is simply too dear to have been paid without lessons learned. If we know that:

- The current housing system creates conditions that make people more vulnerable to respiratory health problems.

- These issues increase the chances of someone dying from easily communicable diseases.

- These burdens fall disproportionately on our city’s Black neighborhoods.

Then it is clear that we have a public health obligation to center these impacted communities in our response to the pandemic. If we are to avoid repeating the mistakes that have led up to this racist outcome, then we must come to the reality that race is key to this conversation. If we do that, then there is no other option than creating policies that remedy these long-standing issues that are leading to such a heavy toll in the Black community. As we look #BeyondRecovery and at how to create a #JustEconomy, we will have to stop doing things the way that we have been going about them. We need to formulate new ways of approaching housing and capital access that allows for true fairness and will lead to better health outcomes for Black families in our region and communities of color across the nation. This will mean understanding what we are doing wrong, if we really hope to build something closer to the Beloved Community. In housing and finance, we can already see so many of the things we are doing wrong. On one hand, the pandemic shows that the inequities in housing are so extreme that one doesn’t need to look very hard. On the other hand, these glaring problems provide us clear signposts pointing us in the direction of the necessary work ahead.

Housing advocates in St. Louis (and elsewhere) need to seize the opportunity that the public attention around COVID-19 has brought to the intersection of health and housing. As more and more people come to believe that #HousingIsHealthcare, it will be up to us to help turn that awareness into action and that action into results. Let’s get to work.