Faulty Foundations:

Mystery-Shopper Testing In Home Appraisals Exposes Racial Bias Undermining Black Wealth

October 2022

Photo: ©Brian Jackson – stock.adobe.com

Jake Lilien, Counsel for Fair Housing Enforcement, NCRC

— Key Takeaways

Appraisers assigned higher values to homes when they believed the owners were White in NCRC’s groundbreaking “mystery shopper” investigation.

One interracial couple’s home was appraised $46,000 higher when the White partner presented it. On average, White homeowners obtained higher values than their Black partners.

Black homeowners experienced unprofessional treatment from appraisers. White homeowners did not.

One appraiser refused to complete an assignment for a Black homeowner. Another took 11 weeks to complete a report for a Black homeowner.

The severity and subtlety of racial bias captured in our findings suggest that it will take sweeping and aggressive action from both policymakers and the industry itself to rid the appraisal marketplace of discrimination.

Introduction

The way that homeowners, lenders and policymakers use the term “property values” often implies that there is one organic, objective, correct definition of what someone’s home is worth. But that is not the case. Our cultural conception of property values obscures the fact that those values are often determined by human beings.

Professional appraisers make mistakes like anyone else. They carry biases, whether conscious or unconscious, into their workplace.

The consequences of an appraiser’s mistakes are far more serious than most people’s workaday errors, however. A store clerk who rings something up wrong can charge it back. A bartender who pours the wrong beer can turn around and serve the right one. But an appraiser’s mistakes, misjudgements or prejudices can derail generations of work to build wealth within a family. The treatment a homeowner receives during the process of selling their home can have serious impacts, especially if outright discrimination is involved. And an undervaluation of a home is rarely corrected. Discriminatory treatment is harmful (and should be prevented) in any setting; in the context of home appraisals, it often comes with severe economic consequences.

With racial wealth and homeownership gaps continuing and even widening[1] despite decades of public policy changes and private sector promises, NCRC asked a simple question: Are appraisers treating Black and White homeowners differently? To find out, we recruited Baltimore-area homeowners to participate in a series of seven “mystery shopper” tests to probe for racial bias in home appraisals. NCRC has more than 20 years of experience in designing, refining and executing mystery shopper testing in housing and lending markets to probe for biased or discriminatory business practices. To our knowledge, this is the first time that an investigative report of this nature has been published.

NCRC recruited multiple interracial couples who own homes in the Baltimore metropolitan area to serve as testers. For each of seven tests, we hired two appraisers to appraise a home owned by a Black/White interracial couple. The appraisers were chosen randomly. When one appraiser arrived at the home to conduct an inspection, only the Black homeowner was present. When the other appraiser arrived at the home to conduct an inspection, only the White homeowner was present. The home’s decor was also modified to represent the race of the homeowner meeting the appraiser. When the White homeowner met with the appraiser, all traces that a Black person lived in the home were removed. The opposite was done when the Black homeowner met with an appraiser.

Using interracial couples as testers allowed us to see whether the same home would be valued differently based on the skin color of the person presenting it to the appraiser. NCRC had two goals with this investigation. The first was to determine whether the Black and White testers would be given the same treatment by appraisers. The second goal was to determine whether the race of the perceived homeowner would affect the appraisers’ valuations of the homes.

Our testing found that Black homeowners were treated far worse than White homeowners. The results further showed that the appraisers assigned higher value to a home when they met with the White partner than when the same property was shown by the Black partner in the couple. Our White testers received valuations that were almost $7,000 higher, on average. The most glaring examples were a home that was valued 12.9% higher when the White spouse presented the home (a difference of $40,000), and a home that was valued 9.1% higher when the White spouse presented the home (a difference of $46,000).

Section I: Background

Communities of color, in particular Black communities, have suffered greatly from generations of segregation, neglect and wealth-stripping. Segregationist laws and racially restrictive covenants, hand in hand with disparities in public and private investments, kept people of color confined to neighborhoods with poor schools, amenities and public services for decades. Many communities of color were torn apart in order to make way for public works such as highways and bridges.

In addition, government-sanctioned redlining denied home loans to applicants if their neighborhoods were heavily populated by Black families, Latino families or other supposedly “high-risk” ethnic groups. One of the architects of redlining was a Federal Housing Administration (FHA) employee named Frederick Babcock, who also played a key role in establishing racially biased home appraisal practices.[2] In Babcock’s influential 1932 textbook on appraisal practices, titled The Valuation of Real Estate, he instructed that racial integration in a neighborhood should be seen as a negative influence on the value of its homes, and even encouraged northern states to adopt the segregationist policies of southern states.[3] There remains to this day a considerable homeownership gap between Black and White Americans. A 2016 study estimated that if the financial benefits of homeownership were equalized, the Black-White wealth gap would be reduced by 16%, and the Latino-White wealth gap would be reduced by 41%.[4] Census Bureau data for the first quarter of 2022 shows a Black homeownership rate of 44.7%, and a Latino homeownership rate of 49%, compared with 74% among the non-Hispanic White Census category.[5]

It is a gross injustice that people of color who have overcome these obstacles, and achieved the goal of homeownership, are unable to obtain fair, accurate appraisals of their homes because of racial bias. Homes in communities of color are routinely undervalued. Many homeowners have reported discrimination by appraisers based on their race. When homeowners are unable to get fair appraisals, it can prevent them from refinancing, lower the prices at which their homes sell and even jeopardize the sales of their homes altogether.

There is ample data showing that racial bias has a significant effect on the appraisal market. A 2021 Freddie Mac study compared the appraisal values assigned to single-family homes with the contract prices for which the homes were actually sold. The study revealed that homes in majority-Latino neighborhoods and majority-Black neighborhoods were far more likely to be undervalued. Sale prices exceeded appraiser valuations for 15.4% of homes in majority-Latino neighborhoods and 12.5% of homes in majority-Black neighborhoods, compared to only 7.4% of homes in majority-White neighborhoods.[6]

A 2018 report by the Brookings Institution compared appraisals of similar homes in neighborhoods that have similar amenities but different racial demographics. The report showed that a home in a neighborhood in which half of the residents are Black will be assigned an appraisal value that is 23% lower on average than a home in a neighborhood that has few or no Black residents – even if the homes and the neighborhoods have the same features and qualities. This difference in valuation is estimated to result in $156 billion in cumulative losses for Black neighborhoods.[7]

One factor that likely influences appraisal bias is the severe lack of diversity in the appraisal industry. Bureau of Labor Statistics data indicates that 97.7% of real estate appraisers are White and 69.6% of appraisers are men, making it one of the least diverse professions in the United States.[8] In order to become certified, appraisers must generally undergo a lengthy apprenticeship with an established appraiser. Many appraisers are unwilling to take on an apprentice outside of their familial and social circles, which allows the profession to remain overwhelmingly White.

Sociologists Junia Howell and Elizabeth Korver-Glenn examined the state of the appraisal market in Harris County, Texas, where they interviewed appraisers. One appraiser told them that when ethnic minorities move into a neighborhood, they lower the neighborhod’s socioeconomic status. Another appraiser made it clear that he viewed all communities of color as being comparable, regardless of their socioeconomic characteristics. This appraiser also stereotyped neighborhoods of color as being poorly maintained.[9]

There have been several high-profile accusations of appraisal bias in recent years, in which Black-owned homes received higher valuations when White people posed as the owners. These cases all started the same way: A Black homeowner ordered an appraisal, met the appraiser and was then shocked when their home received an extremely low valuation. The Black homeowner later hired a second appraiser and arranged for a White friend to pose as the homeowner. The values that these new appraisers assigned to the homes were substantially higher.

One example is the case of Paul and Tanesha Austin, of Marin City, California. Their home was valued at $995,000 by an appraiser who knew that the home was Black-owned.[10] When they hired another appraiser and asked a White friend to take their place when meeting the appraiser, their home was valued at $1.48 million.[11]

In another case, an appraiser valued a Black couple’s Baltimore home at $472,000. The homeowners, Drs. Nathan Connolly and Shani Mott, enlisted a White colleague to present the home to a different appraiser, who valued it at $750,000.[12] The experiences of homeowners such as the Austins and Drs. Connolly and Mott have raised awareness about the extent of racial bias in the appraisal market.

Section II: Methodology

The incidents described above, in which Black homeowners recruited White friends to take their place when meeting with appraisers, inspired NCRC’s testing investigation. NCRC has over 20 years of experience in conducting matched-pair testing in areas such as home rentals and sales, lending, insurance and public accommodations. NCRC devised a methodology to test racial bias among appraisers by monitoring whether Black and White partners were treated differently by appraisers when showing the same homes.

In order to conduct the testing, NCRC recruited four interracial couples who own homes in the Baltimore metropolitan area. Fourteen different appraisals were conducted as part of seven tests. Each test was centered around a home that is owned by one of the couples who participated in the study.

In each test, two appraisal companies were hired at random to conduct full appraisals of the home in question. A full appraisal involves the appraiser coming to the property in person and examining both the exterior and interior of the home. It was essential to the testing that the appraisers conducted full appraisals (rather than exterior-only appraisals, often referred to as “drive-by appraisals”) so the appraiser would meet a homeowner face to face and observe the homeowner’s race.

Both appraisal management companies and appraisal firms were selected for testing. Appraisal management companies generally engage appraisers as independent contractors, while appraisal firms generally have appraisers as employees. These companies were selected at random using Google business listings.

In each test, the appraisal companies were called on the same day, and the appraisals were scheduled on separate days, as close together in time as possible. When one appraiser arrived to conduct the home inspection, they were greeted only by the White homeowner, who was the only family member present. The home had been “whitewashed,” meaning that all family photos were taken down before the appraiser arrived, as well as any cultural items that might be associated with African-Americans (such as African art, or movie posters with Black actors on them). The appraiser was given no reason to think that any Black people lived in the home.

When the other appraiser arrived to conduct the home inspection, they were greeted only by the Black homeowner. The home had been “blackwashed,” meaning that the same precautions were taken to ensure that there were no signs of White people living in the home. None of the testers’ family members were home when the appraisers arrived.

The testers were provided with report forms to describe any communications that they had with the appraisers, and the interactions that they had with the appraisers when the home inspections were conducted. Once the testers received the appraisal reports they sent them on to NCRC staff.

Section III: Testing Outcomes and Findings

NCRC’s testing produced data in three different areas.

- Quality of customer service:

- What information did appraisers give to the testers?

- How quickly did appraisers provide reports after inspecting the homes?

- Did appraisers reach out to testers after inspecting their homes?

- Valuation:

- Did the two appraisers provide both testers with valuations of their homes?

- Is there a significant difference in the valuations?

- Adherence to industry standards:

- When selecting comparator homes in the surrounding market, did appraisers choose homes that were close by, or did they choose homes from outlying areas?

- If they chose homes from outlying areas, did the areas have similar racial demographics to the neighborhoods where the homes were located?

- How many homes did they choose?

The largest discrepancies between the experiences of the Black testers and the White testers were in the area of customer service. Seven tests were conducted overall. In each test, a home was appraised twice. In all seven of the tests, the White testers had pleasant experiences with the appraisers with whom they met, and they received their appraisal reports within 22 days of their homes being inspected, if not sooner.

In two of the seven tests, the appraisers who met with Black testers provided exceptionally unprofessional service. The remaining five tests involved the Black and White testers receiving similar levels of customer service. One of the appraisers who provided a Black tester with unprofessional service was later tested again, when we hired him to appraise a different home, and selected a White homeowner to meet with him. The appraiser provided much more prompt and courteous service to the White homeowner.

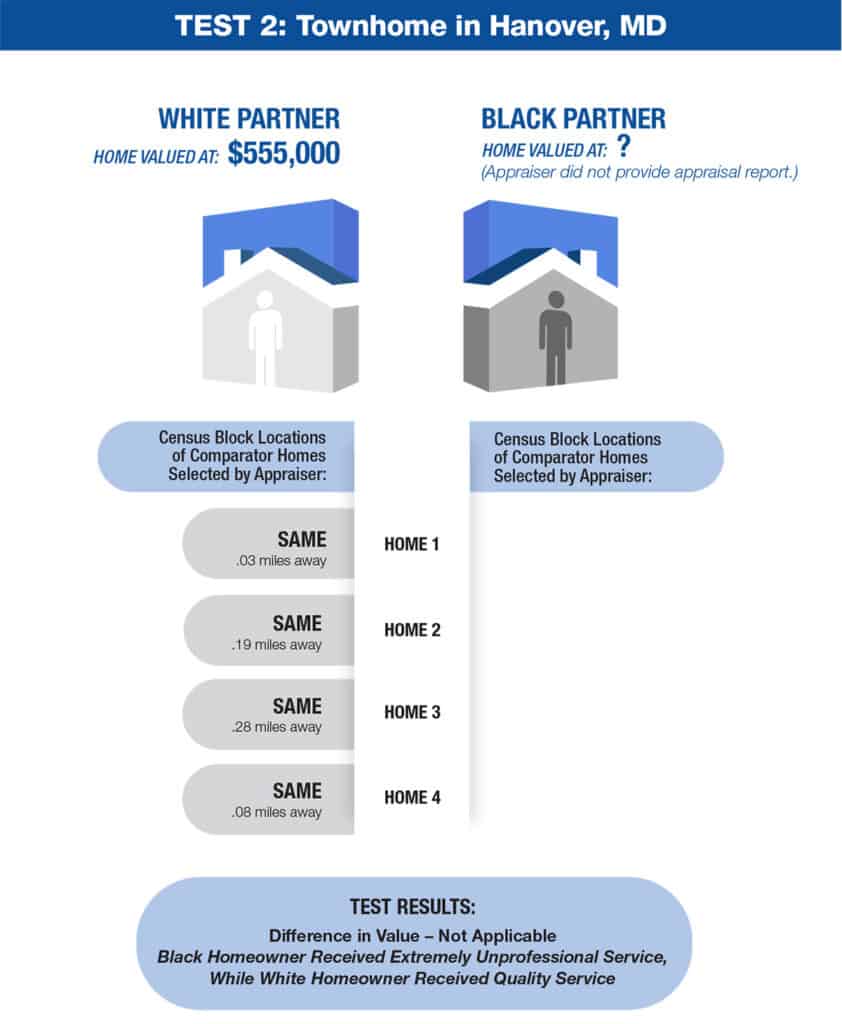

Test Two: In the second of the seven tests, one of the appraisers explained that he would inspect the home in question before requesting payment, but only issue his report after being paid. When this appraiser arrived at the property, he was greeted by the Black homeowner. The appraiser inspected the home, which had no family photos or cultural objects on display that would suggest that any White people lived in the home.

NCRC expected the appraiser to reach out about payment after completing the inspection. He did not. When the appraiser was contacted about the next steps, he claimed that he had already emailed the appraisal report, and he asserted that he would email the report again to multiple accounts. No email was ever received in any of the accounts, and the appraiser then refused to respond to attempts to reach him by email, text and phone.

The appraiser never issued any kind of report, or requested payment. The appraiser also never provided any explanation for why he failed to complete the assignment. The White tester, on the other hand, received a report and was not subjected to any unprofessional treatment whatsoever.

This was a frustrating experience for the Black tester, as he was denied an appraisal report that he was expecting. He had gone out of his way to be available at the time of the inspection. He had also allowed a stranger into his home, all for nothing. In contrast, the White tester’s experience was positive.

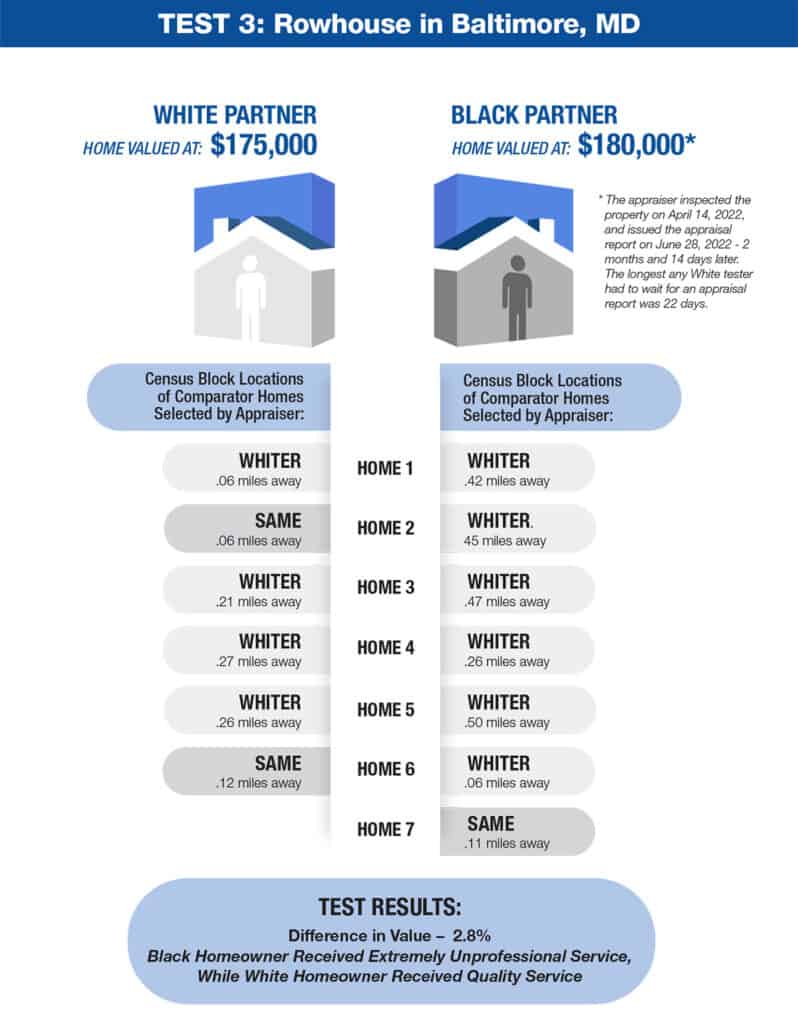

Test Three: In the next test, two different appraisers were hired to appraise another home owned by an interracial couple. The appraiser who ultimately met with the Black homeowner requested and received payment up front. This appraiser then inspected the home on April 14, 2022, and was greeted by the Black homeowner. The appraiser then made no contact until turning in the appraisal report on June 28, 2022.

While the homeowner was waiting for the appraisal report, the appraiser failed to return a phone call asking when the report would be ready. Finally, the appraiser sent an email in June with the appraisal attached. This took place two-and-a-half months after the inspection. The only recognition of the lateness of the report was a comment in the email that said, “Many thanks for your patience with me completing and sending this report.”

Typical home appraisals “take anywhere from a few days to a week depending on the complexity of the property, the appraiser’s schedule and other varying factors,” according to a May 2022 article from Rocket Mortgage.[13]

The Black tester in Test Three had to wait nearly 11 weeks after inspection for the appraisal report to be issued. This is clearly far outside of any industry norms for a residential property. The longest that any of the White testers had to wait for an appraisal report was 22 days after the inspection took place.

This unprofessional behavior shown to the Black tester in Test Three was more than discourteous; it could actively undermine a family’s wealth-building by impeding a sale and/or increasing the cost of borrowing, among other harms.

If the Black tester from Test Two or the Black tester from Test Three had been seeking appraisals because they were selling their homes, they would have lost valuable time waiting for an appraisal report to be returned. The lost time could have easily jeopardized the sales of their homes.

The lost time also could have had major implications for pursuing loans. During the time that the Black tester from Test Three was waiting for the appraisal report to be returned, interest rates were raised considerably. On June 15, 2022 – 13 days before the appraiser issued the appraisal report – the Fed raised interest rates by three quarters of a percentage point, which was the biggest hike in decades.[14] If the tester decided to pursue a home refinance after learning the home’s value, it would have been too late to secure a loan with a lower interest rate.

NCRC attempted to re-test the appraisers from Test Two and Test Three who treated Black homeowners unprofessionally by hiring them to appraise different homes for subsequent tests.The two appraisers proceeded to engage in conduct that indicated that their previous unprofessionalism was not isolated, but was part of a pattern and practice. The appraiser from Test Two did not respond when offered an assignment appraising a home in a Baltimore neighborhood where 80% of residents were people of color. This appraiser previously agreed to appraise a home in Test Two which was located in predominantly-White Hanover, Maryland, a town 25 minutes’ drive from Central Baltimore, in which there are almost twice as many Whites as Blacks.

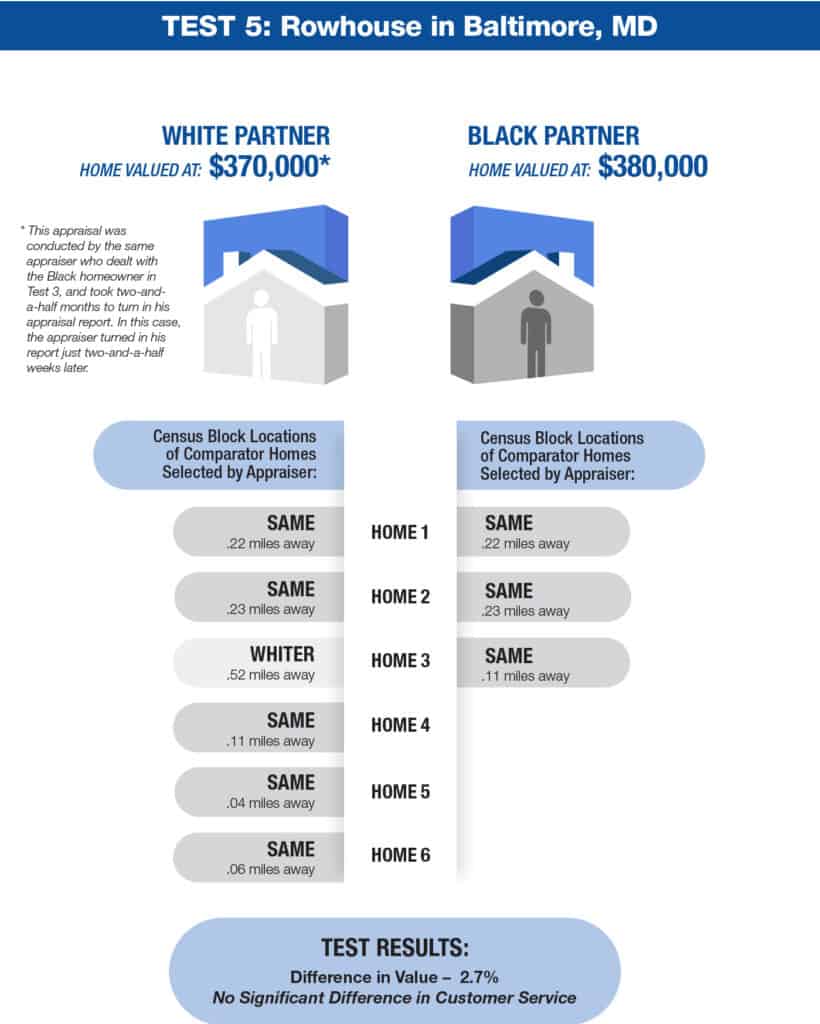

Test Five: The appraiser who had made a Black homeowner wait two-and-a-half months for a report in Test Three was re-tested. He agreed to appraise a different home in Baltimore. This appraisal was part of Test Five. The appraiser met with a White homeowner when he inspected their home on June 14, 2022. On June 23, just nine days later, the appraiser emailed the homeowner to say that the appraisal report should be ready “by the beginning of next week.” (He sent no such email to the Black homeowner during Test Three, despite the extreme lateness of the appraisal report.) The appraiser emailed the completed appraisal report to the homeowner on July 1 – just 17 days after the home inspection.

There is a stark difference between how this appraiser treated a Black homeowner and a White homeowner. The Black homeowner in Test Three had to wait two-and-a-half months to receive the appraisal report, while the White homeowner in Test Five received an appraisal report in two-and-a-half weeks. The appraiser also showed courtesy to the White homeowner by reaching out to explain when the report would be ready. The same appraiser showed no such courtesy to the Black homeowner, and did not even respond to a voicemail message asking when the report would be ready.

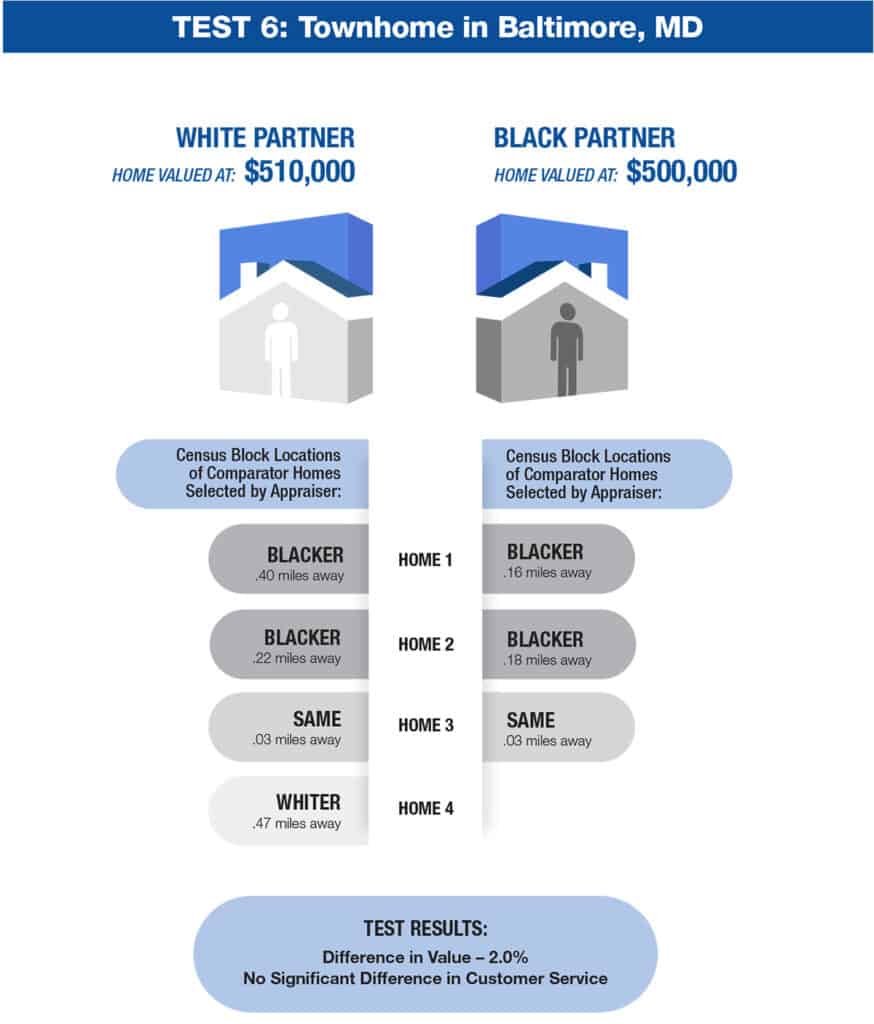

Differences in Valuation

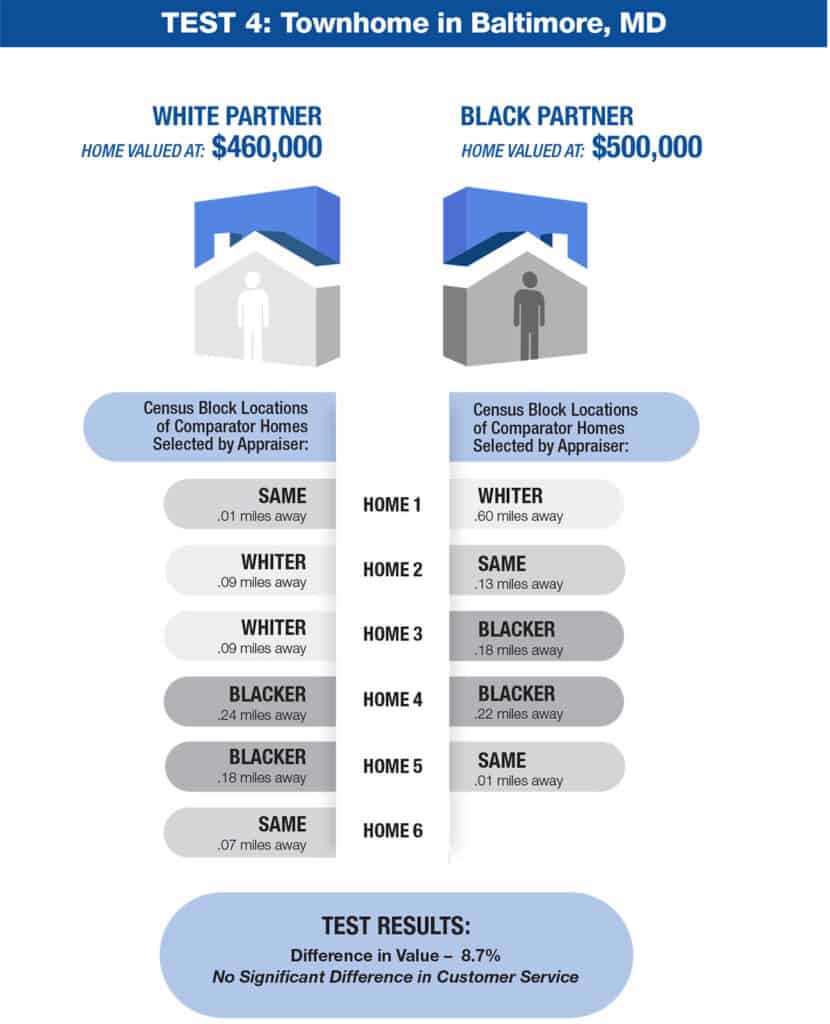

There were six tests in which both appraisers provided appraisal reports. The total of the valuations provided to the White homeowners was $2,418,000. The total of the valuations provided to the Black homeowners was $2,377,000. This means that the average value provided to a White homeowner was $6,833.33 higher than the average value provided to a Black homeowner.

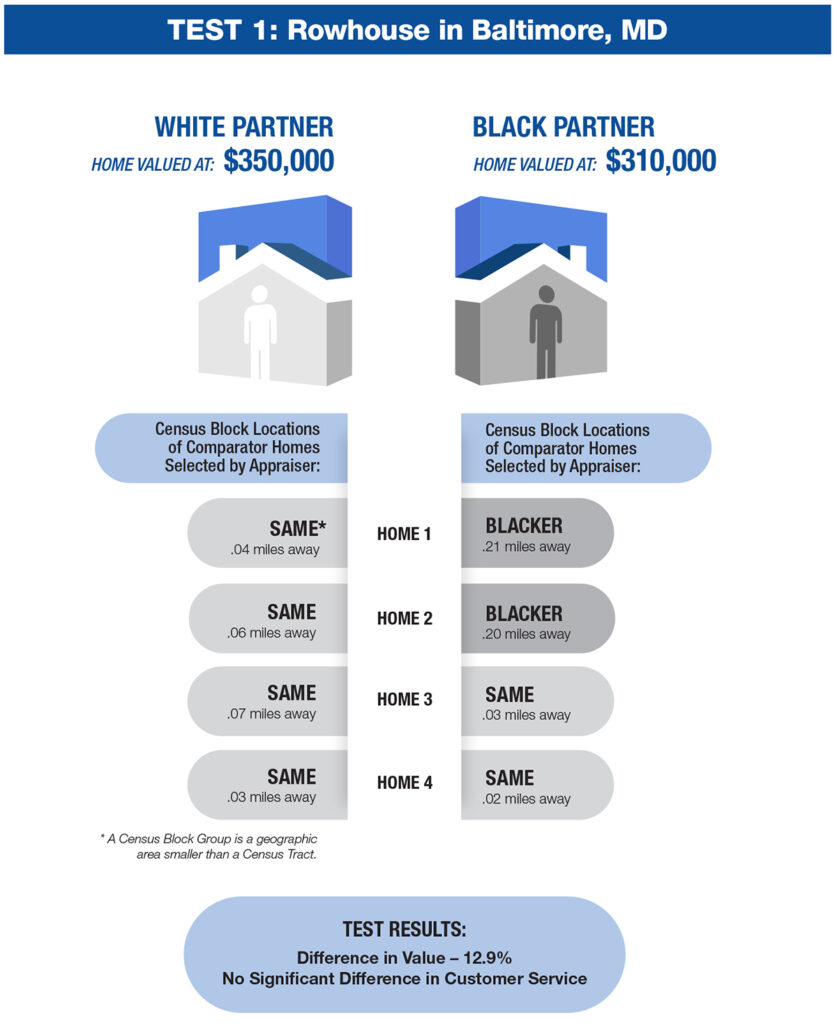

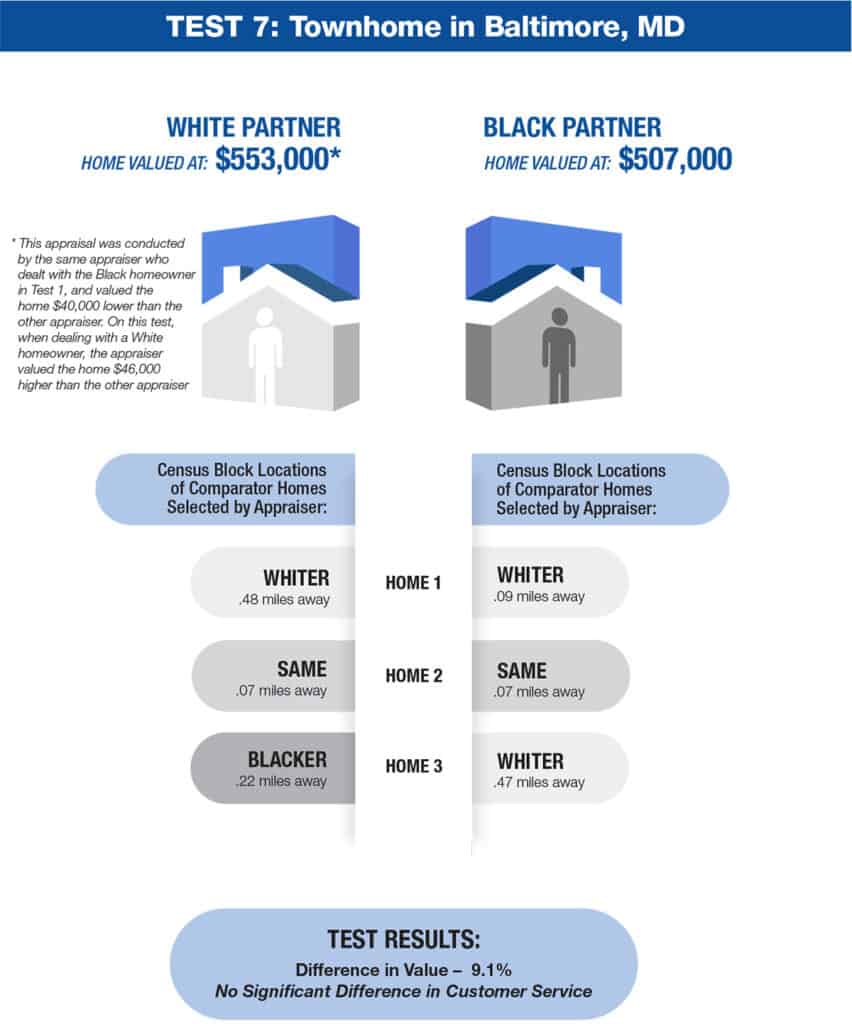

In Test One, the Black homeowner was provided a value of just $310,000, while the White homeowner was provided a value of $350,000 – an increase of 12.9%. NCRC re-tested the appraiser who worked with the Black homeowner. The appraiser agreed to appraise another home in the same Baltimore neighborhood. This appraisal was part of Test Seven.

In Test Seven, the appraiser from Test One met with a White homeowner. The appraiser assigned the home a value of $553,000. The other appraiser, who met with the Black homeowner, assigned the home a value of $507,000. The home increased 9.1% in value when the White homeowner showed it.

Differences in Selection of Comparator Homes

One of the most common forms of evaluating a home’s worth is called the Sales Comparison Approach. In this approach, an appraiser will search for similar local properties that have recently sold. Sales comparisons are a vital part of home appraisals. The Sales Comparison Approach requires the use of at least three comparator homes. Appraisers will often choose more than three.

In NCRC’s testing, the appraisers who met with White homeowners chose more comparator homes than the appraisers who met with Black homeowners. In the six tests in which both appraisers provided appraisal reports, the appraisers who met with White homeowners selected 29 homes as comparators, while the appraisers who met with Black homeowners chose only 25 homes.

The use of improper comparator homes can be discriminatory, if the homes are chosen because of the ethnic composition of their neighborhoods. For example, if an appraiser is preparing an appraisal report for a Latino homeowner, and the appraiser chooses comparator homes in Latino neighborhoods, despite the presence of homes in closer areas that are more similar to the home being appraised, this could be a violation of the Fair Housing Act: The appraiser is basing a home’s worth on the demographics of its owners rather than the state of the property itself. The use of inappropriate comparator homes can take hundreds of thousands of dollars off of a home’s valuation.

NCRC analyzed how far away the comparator homes were located from the homes being appraised and whether the comparator homes located in other areas were in Blacker or Whiter neighborhoods. The results suggested bias against Black homeowners in both categories.

Distance of Comparator Homes:

The comparator homes chosen by the appraisers who met with Black homeowners were, on average, 39% further away than the comparator homes chosen by the appraisers who met with White homeowners. Some of the comparator homes were located half a mile or further from the homes being appraised, in neighborhoods with substantially different demographics.

The use of comparator homes from other neighborhoods can be helpful in some instances when establishing the value of a home. For example, when appraising a home in a majority-Black neighborhood, the best comparator may be a home in a different neighborhood that is majority-White. However, when a Black-owned home is located in a majority-White neighborhood, it is discriminatory for appraisers to look only in majority-Black neighborhoods for comparators.

The race of the homeowner should never make a difference to the choice of comparators. The 39% disparity in distance raises concerns that appraisers’ selection of homes were influenced by race.

Demographics of Comparator Homes’ Neighborhoods:

Appraisers working with Black homeowners were slightly more likely to select homes in Blacker areas as comparators.

Half of the 58 comparator homes that were used by the appraisers were located in the same Census Block Groups as the homes that they appraised.[15] Of the 29 comparator homes selected from different Census geographies, 18 are located in Census Block Groups that are demographically Whiter than the Census Block Groups in which the appraised homes are located. The other 11 homes are located in Census Block Groups that are demographically Blacker.[16]

The majority of the comparator homes in Blacker areas were chosen by appraisers who met with Black homeowners. Half of the comparator homes in Whiter areas were chosen by appraisers who met with White homeowners, and half were chosen by appraisers who met with Black homeowners. Specifically, the appraisers who met with Black homeowners selected six of the 11 homes located in Blacker areas, while the appraisers who met with White homeowners selected nine of the 18 homes located in Whiter areas.

Section IV: Recommendations

NCRC’s testing provides a new window into the discrimination that homeowners of color may face when getting their homes appraised. Our findings add to the considerable pre-existing evidence of racial bias within the real estate appraisal industry. It is clear that action needs to be taken in order to make the appraisal marketplace more equitable.

NCRC’s first recommendation is for more testing. This testing project contained several limitations that future appraisal testing projects may be able to overcome.

This project was limited to Black and White testers. Future testing projects will ideally include testers of other ethnic and racial backgrounds. For example, the Freddie Mac report referenced in Section I showed that homes in predominantly Latino neighborhoods were even more likely than homes in predominantly Black neighborhoods to be undervalued. A testing project that includes Latino testers would provide valuable data.

Most of the Baltimore homes used in the study were located in areas where the population is at least 75% Black. Only one test (Test Two) involved a home located in a majority-White neighborhood. An ideal testing study would contain a significant number of homes in both majority-White areas and areas where people of color are in the majority.

A new study involving Asian and White testers, for example, could include several homes in majority-Asian neighborhoods and several homes in majority-White neighborhoods. This could produce data on the experiences of four different types of testers: Asian testers presenting homes in predominantly Asian neighborhoods, White testers presenting homes in predominantly Asian neighborhoods, Asian testers presenting homes in predominantly White neighborhoods, and White testers presenting homes in predominantly White neighborhoods.

Fannie Mae’s report on appraisal bias examined the overvaluations of White-owned homes in majority-Black neighborhoods. Nearly 50% of these overvaluations occurred in one of the states of Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi, North Carolina, and South Carolina.[17] These would be ideal states for testing.

Another limitation of this study was that six of the seven tests involved couples consisting of a Black woman and a White man. Test Two was the only test that involved a different racial/gender dynamic. (The couple that participated in Test Two consisted of a Black man and a White man. Neither tester divulged their sexual orientation to the appraiser with whom they met.) Future studies should ideally have a greater mix of racial/gender combinations to generate comparisons of results between men of color, women of color, White men and White women.

NCRC also has several policy recommendations.[18]

- Create incentives for the appraisal industry to recruit a more diverse apprentice pool. A crucial tool for reducing bias in the appraisal industry is increasing diversity within the profession. Having a more diverse workforce, particularly in the areas of race, gender, and age, would allow the industry to better serve the increasingly diverse population of the U.S. Incentives are needed for appraisers to take on apprentices from different backgrounds. In addition, there should be paths to certification for aspiring appraisers outside of the traditional apprenticeship system.

- Require appraisal companies to report demographic data on clients and valuations. There would be far more accountability for appraisals if there was a broad-reaching reporting requirement for appraisal companies. The Home Mortgage Disclosure Act (HDMA) has done a great deal to provide the government and the public with valuable data about mortgage lending, by requiring that some financial institutions report on the demographics of their applicants and borrowers, and the pricing of their loans. It would be incredibly helpful for transparency in appraisals if appraisal companies were required to report on the demographics of their clients, and the values they assigned to the clients’ homes.

While such a program is being created, it would be helpful for government-sponsored enterprises to share more of their appraisal data. In recent years Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac have collected data on millions of home appraisals and they have provided useful reports on appraisal bias. However, not all of the data has been publicly released. The Federal Housing Finance Agency (FHFA) should exercise its authority to direct Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac to publicly release more of their data related to appraisal values and the races of the homes’ owners, which would be beneficial for fair housing advocates and homeowners.

The results of this study suggest that some appraisers may be unwilling or reluctant to appraise homes owned by people of color. An ideal federal reporting requirement for appraisers would track not only the assignments that they accept, but also the assignments that they turn down.

- Create a more meaningful reconsideration process. Many homeowners who believe that their homes have been undervalued find the reconsideration process to be unhelpful. Their appraisers are unwilling to engage and make no effort to justify their decisions. If a homeowner or borrower provides information suggesting that a valuation may be flawed as part of the reconsideration process, and an appraiser is unwilling to change their valuation, the appraiser should be required to provide an explanation for why their valuation remains the same.

- Require fair housing training in the licensing process for appraisers. Fair housing training should be mandatory for licensure as an appraiser. It should also be mandatory for experienced appraisers to undergo fair housing training. Proper fair housing training would clarify that appraisal activities are explicitly covered by the Fair Housing Act, and that appraisers are liable for discriminatory acts that violate the Fair Housing Act.

- Increase Funding for Enforcement Resources. Funding to support fair housing testing in the appraisal process (and elsewhere) should be increased, to expand the capacity of fair housing organizations to identify and prevent discrimination.

- Issue Industry Standards for Fair Appraisals. Appraisers should be required to follow protocols that comply with fair housing law, for example in how and where comparator homes are selected. Congress should provide for federal agency authority to issue such standards and provide oversight.

This report is specifically focused on the biases of appraisers. NCRC’s recommendations are therefore focused on identifying and addressing bias within the appraisal industry workforce.

It is worth noting, however, that even if all of the appraisers in the United States began doing their jobs with no biases whatsoever, homeowners of color would still face disadvantages in the appraisal process. For example, racism amongst homebuyers would still play a significant role in lowering the values of homes in communities of color and artificially inflating the values of homes in White neighborhoods. So long as Americans are willing to pay more for homes in predominantly White neighborhoods than in other neighborhoods, homes in communities of color will sell for less, and thus be valued less. Creating a truly equitable environment for homeownership is a broad and important societal undertaking that will go far beyond the confines of the appraisal industry.

Appendix

[1] Jimenez, Nathalie, “America’s Race Gap Between Black and White Homeowners,” BBC News, July 10, 2022, America’s race gap between black and white homeowners.

[2] Adams, Stella, “Putting Race Explicitly into the CRA,” Revisiting the CRA: Perspectives on the Future of the Community Reinvestment Act, February 2009, https://www.frbsf.org/community-development/wp-content/uploads/sites/3/revisiting_cra1.pdf

[3] Dougherty, J. and McGann, S. (2022). On the Line: How Schooling, Housing and Civil Rights Shaped Hartford and Its Suburbs. https://ontheline.trincoll.edu/lending.html

[4] Sullivan, Laura, Tatjana Meschede, Lars Dietrich, Thomas Shapiro, Amy Traub, Catherine Ruetschlin, and Tamara Draut, “The Racial Wealth Gap: Why Policy Matters,” Demos, 2016, https://www.demos.org/research/racial-wealth-gap-why-policy-matters.

[5] U.S. Census Bureau, Quarterly Residential Vacancies and Home Ownership (First Quarter 2022). Available online at https://www.census.gov/housing/hvs/files/currenthvspress.pdf

[6] Freddie Mac, Racial and Ethnic Valuation Gaps in Home Purchase Appraisals (September 20, 2021). Available online at https://www.freddiemac.com/research/insight/20210920-home-appraisals.

[7] The Brookings Institution: Perry, Andre M., Rothwell, Jonathan and Harshbarger, David, The Devaluation of Assets in Black Neighborhoods: The Case of Residential Property (November 27, 2018). Available online at: https://www.brookings.edu/research/devaluation-of-assets-in-black-neighborhoods/

[8] U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, Labor Force Statistics from the Current Population Survey, (January 22, 2021), Available online at https://www.bls.gov/cps/cpsaat11.htm.

[9] Howell, J. and Korver-Glenn, E. (2018). , Neighborhoods, Race and the Twenty-first-century Appraisal Industry. Sociology of Race and Ethnicity, https://static1.squarespace.com/static/573ba69bcf80a1323384f7d6/t/5b9bcb212b6a28b42978ff03/1536936738117/Howell+and+Korver-Glenn+2018+Neighborhoods%2C+Race%2C+and+the+Twenty-first-century+Housing+Appraisal+Industry.pdf

[10] Edwards, Jonathan. “A Black Couple Says an Appraiser Lowballed Them. So, They ‘Whitewashed’ Their Home and Say the Value Shot Up” (Dec. 6, 2021). The Washington Post, https://www.washingtonpost.com/nation/2021/12/06/black-couple-home-value-white-washing/

[11] The Austins’ predicament says a great deal about how racially discriminatory policies of the past continue to affect homeowners of color today. Marin City, where their home is located, is an unincorporated community, which was populated in the 1940s by Black homeowners who were restricted from living in other neighborhoods in the region. Unincorporated communities tend to have lower home values than incorporated communities. Basing the value of a home in Marin City on the sales prices of homes in unincorporated communities can result in a large loss to the homeowners.

[12]Relman Colfax (2022, August 22). Relman Colfax Files Lawsuit Alleging Racial Discrimination in Home Appraisal [Press Release]. Retrieved from https://www.relmanlaw.com/news-437

[13] Araj, Victoria, “How Long Does An Appraisal Take, And What Factors Can Affect the Home Appraisal Process?” (May 13, 2022). Available online at: https://www.rocketmortgage.com/learn/how-long-does-an-appraisal-take

[14] CNBC, “Here’s What the Federal Reserve’s 0.75 Percentage Point Rate Hike – The Highest in 28 Years – Means For You.” (June 15, 2022). Available online at: https://www.cnbc.com/2022/06/15/what-the-feds-highest-rate-hike-in-28-years-means-for-you.html

[15] A Census Block Group is a geographic region that is smaller than a Census Tract. Census Block Groups are the smallest geographic regions for which the Census provides demographic data.

[16] NCRC defines a “Blacker area” as a Census Block Group in which there is a higher concentration of Black residents than in the Census Block Group in which a home is located. NCRC defines a “Whiter area” as a Census Block group in which there is a higher concentration of White residents than in the Census Block Group in which a home is located.

[17] Fannie Mae, Appraising the Appraisal (February 2022). Available online at https://www.fanniemae.com/media/42541/display.

[18] We also appreciate and support the work developed in this area, such as the Action Plan of the groundbreaking interagency Property Appraisal Valuation Equity (PAVE) Task Force, available at https://pave.hud.gov/sites/pave.hud.gov/files/documents/PAVEActionPlan.pdf, which provided insight into the depth of the problems in the appraisal industry, and offered solutions. We would also like to acknowledge the work of our colleagues in the fair housing and fair lending fields, including the National Fair Housing Alliance; see, e.g.,Identifying Barriers and Bias, Promoting Equity, NFHA et al. (January 2022), available at https://nationalfairhousing.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/2022-01-28-NFHA-et-al_Analysis-of-Appraisal-Standards-and-Appraiser-Criteria_FINAL.pdf.

This testing project and report was completed with invaluable assistance from Brad Blower, Marisa Calderon, Robyn Dorsey, Megan Haberle, Richard Lynch, Tracy McCracken, Andrew Nachison, Sara Oros, Jesse Van Tol, and Marceline White.