This article was co-produced and co-published with Nonprofit Quarterly

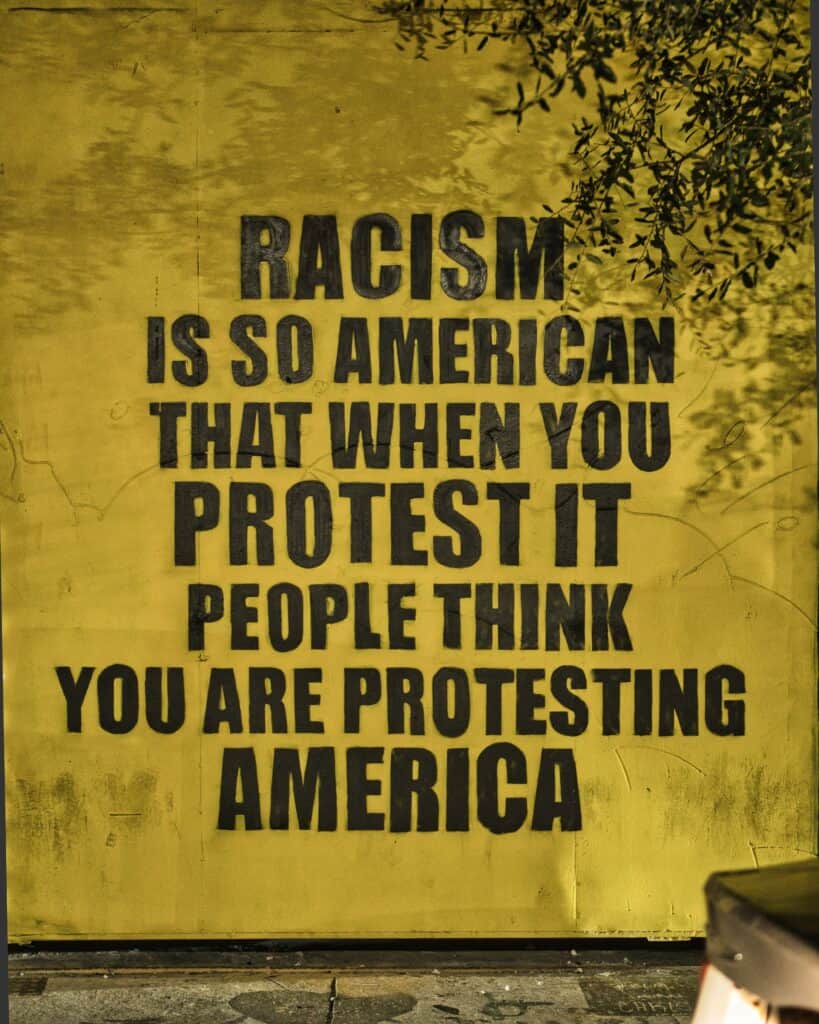

Perhaps the most important lesson the past 50 years should have taught us by now is this: we cannot fix discrimination in housing via an anti-discrimination framework. Conscious race and class measures are needed that tackle the inherent problems of American inequality at their root.

Fred McGhee, Shelterforce

Making a meaningful dent in the level of structural racial economic inequality in this country requires change throughout the US finance system—in our financial regulations, within our financial institutions, and in the lending and investments done by financial institutions. Many of the required changes have been named and identified; it is now up to advocates to build consensus and political power to advance change.

The asset poverty of African Americans, Latinxs, and Native Americans reinforces itself in our current financing system. This racialized asset poverty stems from the theft of Native American lands and chattel slavery of Africans, reinforced through centuries of racist policy and distribution of resources.

In the wake of the civil rights movement, the Community Reinvestment Act (CRA) was enacted. It was one of several important pieces of legislation passed in the late 1960s to early 1970s to address racial economic inequality. CRA was meant to reinforce the Fair Housing Act of 1968, the law McGhee was writing about, which was designed to address housing discrimination and, in turn, advance Black homeownership. The Fair Housing Act was passed only after a massive series of Black urban rebellions, ranging from the Watts uprising of 1965 to the hundreds that followed the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.

Advocates for the Community Reinvestment Act aimed to go beyond simply preventing discriminatory lending practices. CRA explicitly encourages investment in all communities, targeting low- and moderate-income neighborhoods. However, it failed to address racial economic inequality in name and with little impact on minority homeownership. This is a problem. The Black homeownership rate has not substantially changed since CRA was passed in 1977.

Why would a race-conscious approach make a difference? As housing advocate Stella Adams wrote over a decade ago, “The explicit inclusion of race in the CRA offers us an opportunity to correct these government and market failures, and would allow us to do more than just reduce the concentration of poverty and spatial isolation in neighborhoods of color. It would allow us to create opportunities for building real transgenerational wealth for minority families….”

What Would a Race-Conscious Policy Look Like?

The National Community Reinvestment Coalition (NCRC), an organization founded to advance the goals of CRA, is advocating to amend that act to include explicit race-conscious objectives that better address racial economic inequality. NCRC recently partnered with Relman Colfax to produce a paper, “Adding Robust Consideration of Race to Community Reinvestment Act Regulations,” that outlined reforms that would bring a sharper focus on addressing racial economic inequality.

What does a race-conscious approach demand? Part of what is required is tracking the demographics and lending to people and neighborhoods of color. It requires demographic thresholds in the subtests of CRA evaluations, including retail lending, retail services, community development financing, and community development services.

The paper called for creating full-time research positions dedicated to studying the racial components of banks’ varying performance contexts, modeled on work done by the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco. Also, in selecting assessment areas for CRA review, racial inclusion should be a factor to ensure that minority areas are not excluded in assessment areas. Finally, banks should be required to work with organizations serving neighborhoods of color and organizations led by people of color when developing a strategic plan for the Community Reinvestment Act.

These recommendations come as NCRC reveals how current financial practices are maintaining racial inequality rather than bridging it. Home Mortgage Disclosure Act (HMDA) data, shows that whites are the only major racial/ethnic category represented in greater levels of mortgage lending than their demographic representation. In 2020 whites originated 65 percent of all mortgage lending though only 60 percent of the population. The Black and Latinx share of the home lending market—5.2 percent and 9.2 percent, respectively—is less than half their population shares of 14 percent and 19 percent. Native Americans’ representation in the mortgage lending market is even worse. Native American mortgage lending representation at just 0.4 percent is only a quarter of their 1.6-percent share of the US population.

Latinxs, African Americans, and Native Americans are even more poorly served than what has been previously stated if it weren’t for federally backed mortgages like Federal Housing Administration (FHA), Veterans Affairs (VA), and Rural Housing Service (RHS) loans. Almost 60 percent of Black home purchase applications are through these government programs, and for Latinxs, it is about 50 percent. Even with government-backed loans, the private home mortgage market is maintaining the homeownership disparities that are at the center of the American racial wealth divide.

The depth and breadth of racial economic inequality are seen in an array of data points. In 2019, the median Black wealth, not including depreciating assets, was $9,000, and the median Latinx wealth was $14,000, compared to median white wealth of $160,000. In terms of income in 2018, we also see substantial disparity with African American median income at $41,000, Native American at $42,000, Latinx at $51,000, white at $71,000, and Asian American at $87,000. The Black homeownership rate is at a low 42 percent, with Latinxs at 47.5 percent, while at the same time, whites have record-high homeownership rates of almost 73 percent. In 1977—that is, back when CRA was passed—a paper published by the Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago notes that the Black homeownership rate was 43.3 percent, while the white homeownership rate was 67.5 percent—in short, the gap has widened, not narrowed.

How Do We Get There?

Today’s racial economic inequality derives from historic discrimination, exploitation of, and the concentration of wealth. The foundation of racial inequality is racial economic inequality, and the foundation of racial economic inequality is the racial wealth divide. For over the last 40 years the nation has failed to make adequate progress in addressing racial economic disparities.

The pillars of economic anti-discrimination must be transformed through legislation that economically advances communities with a history and current reality of economic marginalization. A race-blind approach to addressing racial economic inequality has left the nation hobbled in public policy efforts to undo ongoing structural racism. It’s far past time that we openly use a racial equity lens to bridge racial economic inequality.

Dedrick Asante-Muhammad is NCRC’s Chief of Membership, Policy and Equity

Photo by Hrt+Soul Design on Unsplash