Netflix’s new TV series, “Selena,” reacquaints fans with the pop sensation’s many hits, including “Bid Bidi Bom Bom” and “Como La Flor,” but it also revisits the family’s turbulent financial journey to stardom. The series showcased 10+ years of financial insecurity in pursuit of a familial dream. The family lost their business and their home. They were forced to move in with extended family and receive public subsidies to get by. The hardships faced by the Quintanilla family mirrors the adversities many Latinx families face today.

In the series, Selena’s parents’ life savings was able to fit in a tin can as they struggled to build their life. This is not uncommon as the wealth gap between Latinx households and White households is stark and has grown significantly since the 1980s. In 1983, the average wealth of a White family was $324,508 compared to the $62,563 average wealth of a Hispanic family (a $256,788 difference). In 2019, the average wealth of a White family was $983,400 compared to $165,500, the average wealth of a Hispanic family (a $817,900 difference). Latinx families operate at a disadvantage when they seek to get by, let alone get ahead.

Like the Quintanillas in the 1980s, many Latinx families are losing their businesses and homes, except now it is the result of the pandemic-induced recession. For many Latinx entrepreneurs, the family’s greatest asset, their home, is leveraged to start a business. When their business goes under as a result of larger economic slumps, the family’s foundation is in jeopardy. This is even more acute during the COVID-19 pandemic as Latinx small businesses, which tend to be in the service sector, have been disproportionately impacted by social distancing mandates. With smaller reserves and fewer resources to draw down, Latinx entrepreneurs have little to fall back on to weather the downturn.

In difficult times, Latinx families need equal access to government subsidies but accessing federal funds has been problematic. When requesting funding from the Payroll Protection Program (PPP), Latinos had their PPP loans approved at half the rate of White-owned businesses. This is no surprise as PPP was distributed through mainstream banks with a history of discriminatory practices toward Latinxs. Investigations into the PPP application process showed Latino testers received significantly less information about PPP loan products than their White males. Latino testers were treated differently through overt statements, and discouraged from pursuing a banking relationship. Instead, the government assistance aimed at helping small businesses survive went to larger corporations rather than mom and pops like Papagayos, Selena’s father’s restaurant.

Latinx families should not be forced to relive the same story almost 40 years later; they need immediate assistance to avoid losing their hard-earned assets. While it seems difficult to get Congress to do anything, the next COVID-19 relief bill must include provisions for the smallest businesses so it reaches Latinx entrepreneurs. In addition, the new administration can help hold banks accountable for their differences in lending by creating regulations that mandate banks to report the racial and ethnic breakdown of their lending patterns. With federal relief in place, and fairness being evaluated among banks, Latinx entrepreneurs and their families will have a better chance at rebounding.

Economic justice is more than ensuring Latinx families have the same access to money as other groups. It’s about ensuring that the community’s potential is not held back by systemic issues. It’s also about making sure the nation supports the Latinx community as it does with other communities when times are hard. There is an abundance of Latinx talent that exists and we must guarantee that more families like the Quintanillas are able to realize their version of the American Dream without restriction.

Sabrina Terry is NCRC’s director of strategic initiatives and development.

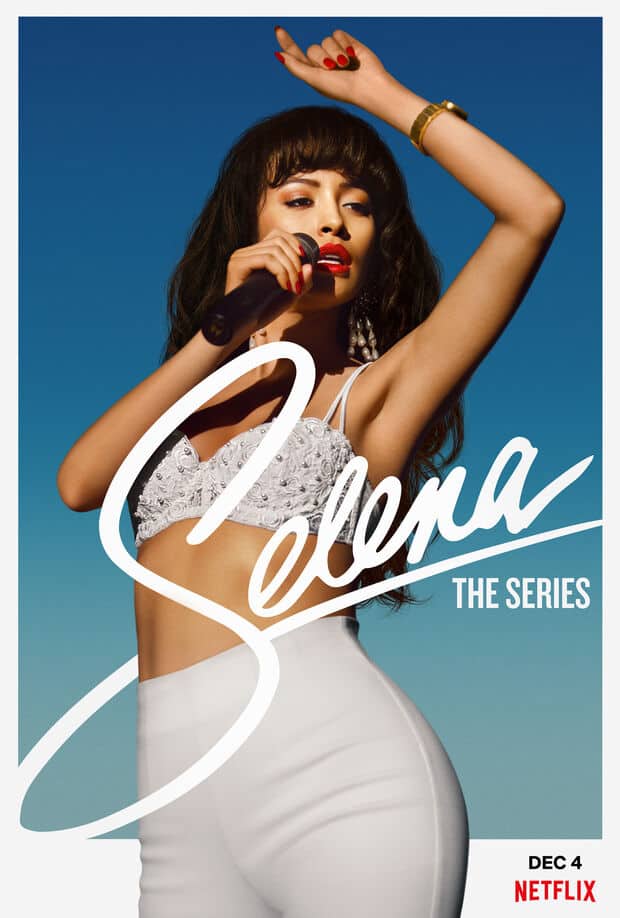

Promotional photo from Netflix.