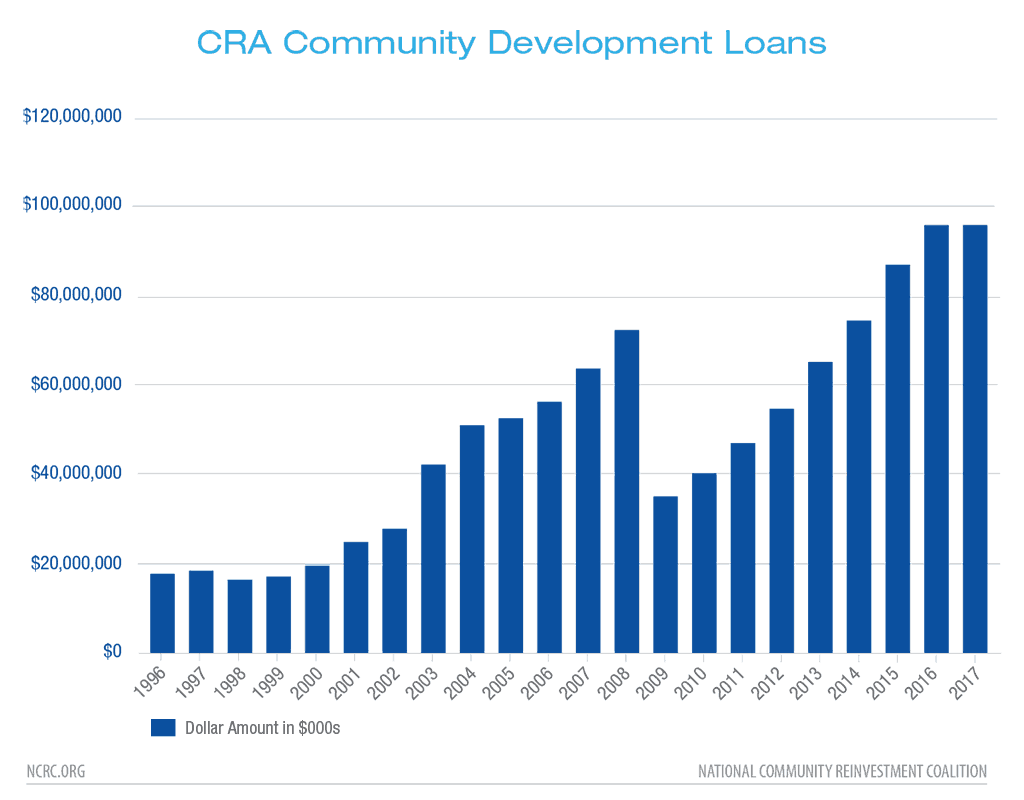

Banks have made more than $1 trillion in community development lending from 1996 to 2017, benefiting low- and moderate-income communities, as a result of Community Reinvestment Act (CRA) requirements.

While this level of financing is impressive, we do not know enough about where it is going in order to determine whether it is targeted effectively to the most underserved and distressed communities. In a recent speech at the 2019 Just Economy Conference, Federal Reserve Governor Lael Brainard suggested that data on community development financing is necessary to assess whether banks are responding to neighborhood needs with their CRA financing.

In 1977, Sen. William Proxmire (D-Wisconsin) spearheaded CRA through Congress in order to combat redlining and direct bank lending to increase investment in low- and moderate-income communities most in need. Now, more than 40 years later, we do a fairly decent job at recording these efforts with the Home Mortgage Disclosure Act (HMDA) and small business loan data, measuring which communities receive access to retail lending, but we do a poor job of identifying the destinations of community development lending and investing.

Community development lending and investing refers to large scale financing of affordable housing or economic development projects that benefit entire neighborhoods. Examples include a 50 unit affordable housing development, construction of a shopping mall or infrastructure such as street/landscape upgrades or broadband access. In contrast, retail lending benefits individual homeowners and small business owners.

For successful revitalization to occur in neighborhoods, retail lending and community development finance need to work in tandem. For example, community development financing of a shopping mall will fail to catalyze revitalization if neighborhood residents live in slum housing and cannot access home loans to buy and/or repair their homes. Likewise, the long term viability of a neighborhood with high levels of homeownership will be imperiled if residents do not have convenient access to grocery stores and other shopping outlets.

In order to measure access to credit, HMDA and small business loan data, which provide stakeholders with reasonable measures regarding access to retail lending, can be analyzed on a census tract level. Census tracts, typically containing 4,000 residents, are a proxy for neighborhoods. They allow CRA examiners, practitioners and advocates to determine economic conditions and lending trends in those neighborhoods. However, data on community development finance is absent on a census tract level. Hence, a full picture of whether revitalization will likely succeed on a neighborhood level is lacking.

Currently, CRA exams and related regulations reveal some data on community development financing but the data disclosure is incomplete and frustrates effective analysis. CRA exams have aggregate data on community development lending and investing for banks’ assessment areas that are typically metropolitan areas or counties but not for census tracts. Usually, the exams will present overall dollar totals for community development financing for each assessment area and will provide some examples of community development financing.

If a reader of an exam wanted to analyze a bank’s level of community development financing for all assessment areas, the reader would have to comb through the exam and manually input the data into an excel spreadsheet. Imagine constructing an excel spreadsheet for a single large bank that may have upwards of 50 to 100 assessment areas. It is a very labor intensive undertaking, and at the end of it, community development data will still be lacking on a census tract level.

In addition to CRA exams, the federal bank agencies provide fragmentary community development data on various websites. The Federal Financial Institutions Examination Council provides summary community development lending data that includes just an overall total in dollars for each bank and all banks in a given year. The Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC) administers a public welfare investment regulation under which banks provide data to the agency on their investment activity.

On a quarterly basis, the agency then publishes data for each bank regarding each investment, its dollar amount, the purpose (affordable housing or economic development) and the metropolitan area or state in which the investment occurred. While this is a useful precedent, it is still incomplete in that not all banks are regulated by the OCC, the data reports only investments, not loans, and the disclosures regarding geographical areas are inconsistent, varying between states or metropolitan areas in the geography data field.

The federal bank agencies are in the midst of considering changes to the CRA regulation and have been asking stakeholders whether a community development database of some sort should be created. This is a very positive development. In recent comment letters, NCRC has recommended that like HMDA and small business loan data, the community development lending and investment data must be submitted annually and publicly by banks on a census tract level, a county level and for assessment areas.

The community development data should also be reported separately for the major categories of community development, including affordable housing, community services, economic development and activities that revitalize and stabilize low- and moderate-income census tracts. Finally, community development loans, investments and grants should be reported separately since these types of financing respond to different needs.

With annual data broken out by geographical area and purpose, examiners, community groups and banks can track bank performance on a more timely basis and correct areas of weaknesses several months before CRA exams. This is a win-win situation as banks are likely to have higher ratings on their exams while communities receive needed financing sooner.

A pressing issue to be considered is how to better address the needs of underserved areas, whether those be census tracts or counties. If the agencies required better community development finance data, they would have the ability to comprehensively measure retail lending and community development financing for each census tract on a per capita basis and thus determine which neighborhoods have a shortage of financing for comprehensive revitalization. The same analysis can be conducted on a county level to identify underserved counties. Bank activity in these underserved tracts and counties could then receive encouragement on CRA exams.

One way to encourage this activity in underserved tracts or counties is for CRA exams to provide special treatment for financing in the areas outside of a bank’s assessment area. Assessment areas are currently areas in which banks have branches. Banks sometimes chafe at the restraint assessment areas impose on pursuing needed community development opportunities.

However, community organizations worry that free reign outside of assessment areas could cause banks to neglect needs around their branch locations and could also facilitate pursuit of community development deals in the easiest areas to finance regardless of that community’s needs. Better community development data on a census tract and county level can address the concerns of banks and community organizations by identifying priority areas of need outside of bank assessment areas, as well as enabling stakeholders to assess whether banks are also meeting needs in their assessment areas.

Protocols would need to be established for ensuring the accuracy of data and prohibiting abusive activity like not allowing financing developers that displace low- and moderate-income tenants to be reported as community development loans and investments. Banks can receive favorable consideration on CRA exams for multifamily lending in low- and moderate-income tracts but NCRC member organizations have reported instances of banks financing unsavory slumlords receiving these loans.

Protocols have been developed over the years for HMDA data and should be feasible to develop in the case of community development data. One of the robustness checks could involve the federal bank agencies consulting any state and local law or best practices about community development, and also investigating community organization concerns about any displacement activity financed by banks in low- and moderate-income communities.

Better community development loan and investment data would be a win-win for both banks and community organizations by facilitating identification of underserved areas. It would also further CRA’s objectives of directing access to credit and capital where it is needed most. If the agencies truly want to reform CRA, the first place to start is with better data.

Josh Silver is a senior advisor of policy and government affairs at NCRC.

Photo Credit: JustGrimes – Data (scrabble)