May 30, 2023

April Tabor

Secretary

Federal Trade Commission

Office of the Secretary

600 Pennsylvania Avenue NW

Suite CC-5610 (Annex B)

Washington, DC 20580

Rohit Chopra

Director

Consumer Financial Protection Bureau

1700 G St. NW

Washington, DC 20552

Re: FTC-2023-0024-0033

Dear Secretary Tabor and Director Chopra:

The National Community Reinvestment Coalition (NCRC) appreciates the opportunity to submit written comments to the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) and the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) to make the tenant screening process more equitable. NCRC and its grassroots member organizations create opportunities for people to build wealth. We work with community leaders, policymakers and financial institutions to champion fairness in banking, housing and business. NCRC was formed in 1990 by national, regional and local organizations to increase the flow of private capital into traditionally underserved communities. NCRC has grown into an association of more than 700 community-based organizations that promote access to basic banking services, affordable housing, entrepreneurship, job creation and vibrant communities for America’s working families.

Currently, many aspects of the tenant screening process limit many low-income people of color’s ability to access rental housing. We recommend strengthened regulation of the following aspects of the tenant screening process to promote nondiscrimination and to help more low-income people of color access high-quality and affordable rental housing: criminal records; eviction records; credit history; source of income; and algorithms in tenant screening. Our comments below discuss how the ways in which housing providers and screening services use each of these criteria, and common algorithmic models as a whole, too frequently contribute to housing insecurity, ongoing vulnerability of low income renters on the housing market, and racial inequality in housing access and conditions. We also provide recommendations for the use of agency authority to better ensure fair outcomes for tenants seeking rental housing.

I. The Tenant Screening Process and Key Criteria with Racial Equity Impacts

A. Background

The tenant screening process must be more closely regulated because landlords increasingly rely on tenant screening technology to select tenants and the process by which tenants are chosen is highly subjective, and can result in disproportionate negative outcomes for renters of color. Landlords often rely on credit scores, eviction records, criminal records, and criteria such as source of income to determine whether or not to extend a conditional offer to prospective tenants.[1] Screening criteria often becomes stricter or more relaxed depending on the housing market; in a market with more available rental units, landlords are more likely to relax these criteria compared to a market with fewer units where they more strictly adhere to these criteria.[2] Conversely, in a market with many qualified applicants, a criminal conviction or past eviction can make it harder for those applicants to find an apartment.[3]

Since the 2008 foreclosure crisis, all prospective tenants, regardless of whether they have a criminal record, have confronted a more competitive rental market since the demand for rental housing increased exponentially.[4] The Great Recession (2007-2009), contributed to a competitive rental housing market.[5] As a result of the Great Recession, many Americans were pushed out of the housing market.[6] Individuals who would have been homeowners prior to the Recession were now competing in the rental market against people with lower incomes and less wealth, thereby driving up the price of rental housing and leaving lower-income renters with less access to a smaller pool of affordable housing.[7] This growing demand for apartments is reflected in gradually increasing rents, as the table below demonstrates.[8] Although the demand for rental housing slowed down early in the COVID-19 pandemic, it crept up in 2021.[9] There are several reasons for an increase in the number of renters by 870,000 from the 1st quarter of 2020 through the third quarter of 2021.[10] They include but are not limited to: millennials entering their prime renting years in their 20s and 30s; the growth in the number of older renters as baby boomers age; the delayed transition to homeownership for many young and middle-aged Americans; and increased demand for rental housing among people of color.[11]

Screening practices’ impact on people of color is twofold. Seemingly neutral criteria disproportionately impact low-income people of color.[12] Additionally, even when intentional discrimination has occurred, landlords have plausible deniability in competitive housing markets.[13] They can simply state that they chose to rent to a more qualified applicant.[14]

B. Criminal Records in the Tenant Screening Process

Prospective tenants with criminal records face an additional hurdle when applying for apartments. Since people of color are disproportionately impacted by the criminal justice system, denying housing based on a criminal record can often, but not always, serve as a proxy for race or can have a disproportionate impact on the basis of race. Banning people with criminal records from applying for housing can disproportionately impact Black and Latino applicants due to their overrepresentation in the criminal justice system.[15] Black people are incarcerated in state prisons at about 5 times the rate of White people while Latinos are incarcerated at 1.3 times the rate of White people.[16]

In recent years, the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) has issued fair housing guidance to housing providers about prospective tenants with criminal records. In 2016, HUD advised housing providers against issuing blanket bans against people with criminal records. In both its 2016 guidance and guidance released in 2022, HUD stated that use of criminal backgrounds in housing could violate the Fair Housing Act if disparate impact or disparate treatment occur and such a policy that causes disparate impact is not necessary to “serve a substantial, legitimate, nondiscriminatory interest of the housing provider,” or if this interest “could be served by another practice that has a less discriminatory effect.”[17] Disparate treatment occurs if an individual who is a member of a protected class receives worse treatment than an individual who is not a member of a protected class.[18] For example, according to both sets of guidance, disparate treatment can occur if a housing provider chooses to share certain information about the application process with a White prospective tenant with a criminal conviction but does not share that information with a Black prospective tenant with the same criminal conviction.[19] Or, a landlord may choose to rent to a White prospective tenant with a criminal conviction but deny that same opportunity to a Black prospective tenant with the same conviction.[20] In both instances, the only difference between the two prospective tenants is race. Choosing to deny housing to someone based on race is a clear violation of the Fair Housing Act.

Furthermore, HUD observed that disparate impact takes place when a seemingly neutral policy has a disproportionately negative impact on members of protected classes unless the housing provider can provide an adequate justification for the policy.[21] Instead of disqualifying all applicants with criminal histories, HUD clarified that housing providers should consider whether an arrest resulted in a conviction.[22] If an arrest resulted in a conviction, the HUD guidance states that the housing provider should consider the nature of the crime committed, so as to assess whether its consideration can reasonably be justified, and should give individualized consideration to the circumstances of the applicant (as a less discriminatory alternative to generalized exclusion).[23]

Despite HUD’s 2016 guidance, recent reports have found that housing providers treated Black people and White people with criminal records differently. The Equal Rights Center conducted 60 matched pair tests in Washington, D.C. and Northern Virginia to determine whether Black women with criminal records were treated differently than White women with criminal records.[24] Its report found that White women received more favorable treatment than Black women in approximately 47% of the tests.[25] A report from the Greater New Orleans Fair Housing Action Center (GNOFHAC) had similar results. The Center conducted 50 paired tests of housing providers in the Greater New Orleans Area to investigate if Black prospective tenants with criminal records were treated differently than White prospective tenants with criminal records.[26] The Center's findings were disturbing:

-

- African American testers experienced differential treatment almost 50% of the time.[27]

- 42% of housing providers discriminated based on race in the way that they explained or applied criminal background screening policies.[28]

- These disparities expressed themselves in the four following ways [29] :

- White testers were informed about more lenient policies than Black testers.[30]

- White testers were provided with better customer service than Black testers.[31]

- White testers were encouraged to apply despite a criminal record while no such encouragement was provided to Black testers.[32]

- Exceptions were made to criminal background policies for White testers but not Black testers.[33]

As this research indicates, more needs to be done to prevent the discriminatory use of criminal records in the tenant screening context.

C. Eviction Records in the Tenant Screening Process

Prior eviction proceedings or actual evictions can pose another barrier to Black and Brown people accessing rental housing. This barrier is especially significant because as many as 5 million Americans are evicted or have their homes foreclosed on annually.[34] According to a 2020 report, Black people are most impacted by eviction–they comprise both the majority of eviction filings and judgments.[35] From 2012 to 2016, Black renters had the highest share of eviction filings and judgments relative to their share of the adult renter population across 1,195 counties in 39 states.[36]

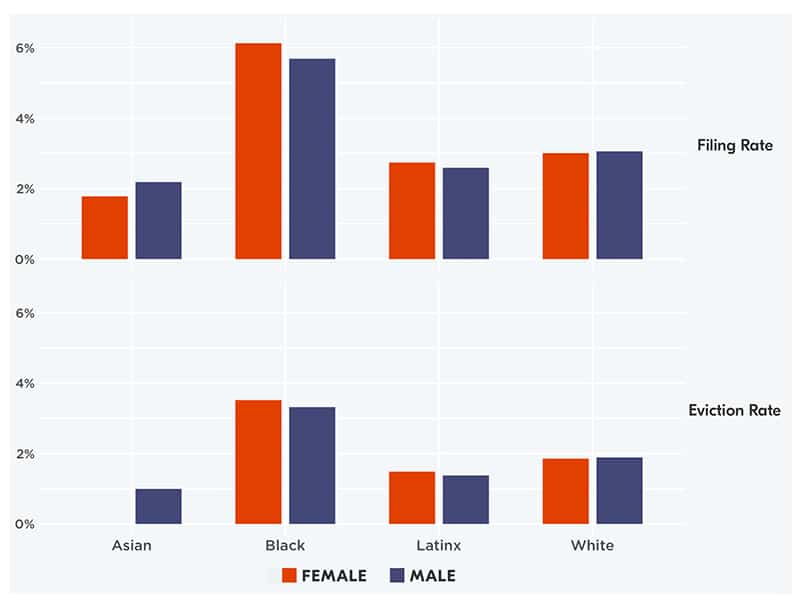

A report from The Eviction Lab corroborates this perspective and further disaggregates this data by race and gender. It demonstrates that Black women have both the highest eviction filing rate and eviction judgment rate (see the graph from The Eviction Lab below).

The reasons why Black rental households have the highest eviction rates are largely economic, but discrimination also plays a role. Black households are more likely to be rent-burdened compared to White households.[37] The disproportionately negative impact on Black renters shows up in the past two years of nationwide eviction filings. In 2021, there were over 540,000 eviction filings across 6 states and 31 cities.[38] 28.5% of filings were against Black tenants and 53.6% were against White tenants.[39] 2021 American Community Survey (ACS) data reveals that 21.2% of renters in these sites were Black while 51.9% White.[40] In 2022, there were almost 970,000 eviction filings across ten states and 34 cities.[41] In 2022, there was an increase in eviction filings against Black renters and a decline in eviction filings against White renters. 31.3% of filings were against Black tenants while 50% were against White tenants.[42]

Some housing providers assert that if someone has an eviction on their record, it is because they could not pay rent in the past and therefore would not make good renters in the future. While this observation might be true in a number of instances, such a generalization can hide the nuances and inequalities baked into evictions. Blanket policies against renting to prospective tenants with previous evictions can have a disproportionately negative impact on Black renters, who tend to be evicted at the highest rates compared to other groups. Moreover, some landlords may file evictions without intending to evict tenants as a way to earn additional revenue.[43] Furthermore, if eviction proceedings took place years ago and the tenant has not had any issues paying their rent since then, or faced an eviction due to particular circumstances of economic distress (such as a job loss), the presence of an eviction on a housing record should not automatically disqualify them.

An eviction may also have occurred because the tenant was the victim of domestic violence. In his book Evicted, sociologist Matthew Desmond found that many women were evicted when the police were called to a property.[44] Some tenants were left with an untenable problem: they could choose to live with their abuser or call the police but accept an eviction. In some states, there are laws prohibiting evictions due to domestic violence-related police reports. Tenant screening companies should permit applicants to seek to have evictions associated with domestic violence removed from their records.

The FTC and CFPB should use their authority to limit the use of eviction records in the rental context, as discussed further in the Enforcement Recommendations section below. Landlords should be required to consider the circumstances of individual eviction records, if they consider past evictions at all.[45] Similar to how mitigating circumstances can be taken into account with criminal records in tenant screening practices, a similar process should be in place for eviction records. For example, the Fair Credit Reporting Act (FCRA) prevents evictions from showing up on a renter’s record if they are the result of a disastrous event like the COVID-19 pandemic.[46] The agencies should clarify additional circumstances in which use of eviction records is inappropriate, in particular if the past eviction does not predict future ability to pay rent. Many eviction proceedings do not result in an eviction, and should not be considered, similar to the way use of arrest records should be excluded.[47] Further, eviction proceedings and evictions may occur for reasons that are unrelated to the future ability to pay rent (for example, due to temporary economic circumstances such as a job loss or medical situation, or due to escalating rent in a gentrifying market) or may occur for reasons other than nonpayment of rent or violations of the apartment lease.

D. Credit Scores in the Tenant Screening Process

Current credit scoring models reflect decades of bias that robbed wealth from Black communities and other communities of color, and can have a disproportionately negative impact on Black and Latino prospective tenants. Housing providers should consider alternative models that are more equitable.

Less wealth means fewer financial resources to pay bills in the event of an emergency.[48] Key events like government-sponsored redlining from the 1930s through the 1960s and the exclusion of Black soldiers from the homeownership provisions of the G.I. Bill following WWII meant that many Americans could not access homeownership, and have the accrued wealth from homeownership to pass down to future generations.[49] Leading up to the Great Recession, people of color were targeted for predatory mortgages.[50] Homeowners of color suffered higher rates of foreclosure during the Foreclosure Crisis, which erased more than $400 billion, and devastated many of these homeowners’ credit scores.[51]

Studies have captured the collective damage that these practices have had on the credit scores of people of color. According to a 2010 study, more than 54.2% of residents in predominantly Black zip codes in Illinois had credit scores lower than 620.[52] In majority-Latino zip codes, 31.4% of residents had a credit score of less than 620, and 47.3% had credit scores that were more than 700.[53] In comparison, 20.3% of Illinois residents had credit scores less than 620, and only 16.8% of inhabitants of predominantly White zip codes had credit scores lower than 620.[54] Scores in mostly White areas are much higher due to decades of advantages that the government provided them with in contrast to the disadvantages that government-sponsored discrimination wrought on communities of color.[55] 67.3% of residents in predominantly White zip codes had scores over 720 while only 25% of residents in predominantly Black zip codes had scores above 700.[56] A 2004 study revealed that White people’s median credit score in 2001 was about 738, but the median score for Blacks and Latinos was 676 and 670 respectively.[57]

Further, errors on credit reports can further damage people of color’s credit scores.[58] A 2013 FTC study of the U.S. credit reporting industry revealed that 5% of consumers had errors on one of their three major credit reports.[59] Inaccurate information in credit reports can unfairly result in lower scores for people of color, who already suffer from lower scores due to systemic racism. The FTC and CFPB should do more to ensure that all consumers’ credit reports are accurate.

In 2022, the FTC received 1.1 million reports of identity theft.[60] As a result of these scams, consumers lost $3.8 billion.[61] Many identity thefts allow scammers to access credit and leave their victims responsible for those debts. Victim of identity theft are left with debt they cannot afford to repay, made vulnerable to housing insecurity, and experiences harms to their credit scores. The problem becomes self-reinforcing: once their identity is stolen, they may lose their housing, and with thereafter be challenged to qualify for new housing.[62] Alarmingly, the credit bureaus themselves have a hand in facilitating the impact of identity theft on consumer financial health. In 2017, Equifax admitted that it exposed the personal information of 147 million consumers.[63] As a result of the ensuing settlement, Equifax was held liable to provide $425 million in relief, including paying for future credit monitoring services.[64] Equifax also agreed to help people restore their credit, but consumers were obligated to seek such services.[65] It is unclear how many harmed consumers found a remedy, many may remain harmed. The FTC and the CFPB should ensure that tenant screening services do not penalize consumers for the presence of derogatory information on their credit histories that is the result of identity theft.

E. Source of Income Discrimination

Landlords’ rejection and economic exploitation of prospective tenants who use housing vouchers to pay their rent presents another challenge for renters when they attempt to access housing. Exclusion from rental housing limits voucher holders’ ability to access safe, decent, and affordable housing.[66] The purpose of the Housing Choice Voucher (HCV) program (more commonly known as Section 8) is to deconcentrate poverty by allowing families to choose where they want to live.[67] Rejecting prospective tenants because they use housing vouchers limits housing choice, particularly for Black renters. Such discrimination can also impede the ability of voucher holders to access safe and healthy housing at all, especially in tight housing markets. According to Fannie Mae, Black renters are overrepresented among voucher holders relative to their share of the renter population. Black people are 20% of the renter population, but comprise 48% of voucher holders.[68] Rejecting renters who use vouchers to pay their rent can thus have an outsized negative impact on Black renters, as well as harm other low-income households. Discrimination on the basis of source of income may violate state or local law that provides protections on this basis, or it may reflect disparate treatment if Black and White holders are treated differently.

The current housing affordability crisis is another reason why landlords should accept housing vouchers. According to a March 2023 report from The National Low Income Housing Coalition, the shortage of affordable rental housing for extremely low-income renters increased from 2019 to 2021.[69] In 2019, the shortage of affordable rental housing was 6.8 million but increased to 7.3 million in 2021.[70] The report also showed the relationship between housing assistance and severe housing cost burdens; as the share of HUD-assisted rental housing increases, the share of severely cost-burdened, extremely low-income renters decreases.[71]

Another way that some landlords mistreat renters who use vouchers is by charging them excessive fees. A March 9, 2023 press release from HUD’s Office of the Inspector General (OIG) to “advance environmental justice in HUD-assisted housing” revealed that some landlords who participate in HUD’s rental assistance programs charged voucher holders more than non-HUD-assisted tenants in rent, utilities, or other fees.[72] In 2022, the U.S. Attorney found that a group of Newark, Delaware landlords violated the False Claims Act by charging voucher holders more in fees and rent compared to tenants who don’t receive assistance to live in comparable apartments.[73] As a requirement of participating in the HCV program, landlords are required to sign a required HCV certification stating that they would not engage in this discriminatory practice.[74] In March of this year, a Holyoke landlord also violated the False Claims Act after she received utilities payments from a low-income tenant that violated her agreement with HUD while she participated in the Section 8 program.[75] Both instances demonstrate how some landlords may deprive low-income households of already precious resources by preying on their vulnerable status as low-income people who are also housing insecure.[76] This indicates the need for an overall strengthening of regulatory and enforcement protections for voucher holders, so that they are treated fairly and are able to attain housing and exercise choice on the market.

II. Artificial Intelligence (AI) in Tenant Screening and Needed Reforms

Service providers increasingly rely on artificial intelligence for tenant screening. Traditional credit scoring models do not use the right information to evaluate the ability of an applicant to pay rent. The current systems cannot score millions of residents. Many of the most commonly used data points contain biases against applicants of color. Algorithmic models are complex and not explainable. The possibility exists for new tenant screening algorithms to serve property owners and residents better, as traditional credit scoring models are often not predictive or fair, but several steps must be implemented to realize those opportunities. This section will focus on how regulators can improve the fairness and transparency of tenant screening models.

A.Use of Positive Payment Data

Research demonstrates that the addition of rent payment history can increase the predictive power of rent payment models.[77] A 2022 study revealed that after 20 years of policy advocacy to support the use of positive payment data (PPD), 2 to 5 percent of consumers who make such payments (rent, utilities, telecommunications bills) have those records on their credit bureau files today.[78] Even though policymakers know that if used appropriately, PPD can reduce the number of thin file and credit invisible consumers (through the voluntary, privacy-protected use of additional data), its promise has not been realized.

The tenant screening market remains focused on negative information. Most tenant screening services use one or several categories of negative information to evaluate an applicant’s eligibility for a lease. They tap records of evictions, criminal records, sex offender status, unpaid checks, and other indicators of potential risk.[79] As noted above, use of this much of this information is itself flawed. The failure to consider alternative or additional positive information about prospective tenants is also harmful, and is a market failure.

B. “High-Risk” Designation, Explainability, and Adverse Action Notices

A proposed European Union law would establish three categories of supervision for artificial intelligence. The framework assigns different levels of regulation to activities, based on the significance of those decisions to human livelihood.[80] Qualifying for housing is among a group of activities that merit a “high-risk” approach for regulation, on the grounds that decisions made in this area hold significant impacts for human well-being. Other examples of high-risk activities include employment, justice, health care, education, and credit availability. As a part of its policymaking on high-risk activities, the EU has required entities to explain how their models came to their decisions.

U.S. regulators should apply a high standard of explainability to algorithmic tenant screen activities. Under FCRA, housing applicants have the right to receive an explanation of information that was used to arrive at an adverse decision. Adverse decisions include not only a rejection of an applicant, but also when an additional contingency (a higher deposit or a special fee) is placed as a condition of approval. We believe that the FTC and the CFPB must update their systems to accommodate the complexity of decisions that are made with AI. The challenges here are consistent with the ones that prompted the CFPB to hold a tech sprint for adverse action notices used to adverse credit application decisions.[81] We encourage the FTC and the CFPB to conduct a sprint for adverse action notices in the tenant screening context as well.

The FTC and the CFPB must expedite the return of information to consumers. It is not satisfactory for an applicant to receive an adverse action notice 30 days – or even 10 days – after receiving an adverse decision. Most decisions to rent an apartment are reached within a relatively narrow time frame. Applicants may have five to ten applications out at any single time. Moreover, as a condition of making those applications, applicants may have paid hundreds of dollars in application fees. Some may apply for several apartments while traveling across town on the same weekend. As a result, they must receive prompt notice. Such a response rate is technically possible; tenant screening services provide answers to property managers within minutes.[82] To be useful, the notice would be delivered in near real-time and in an electronic format so that it can be seen during an apartment search. One solution would be to require tenant screening companies to deliver their reports to both the property management company and the tenant.

The CFPB and FTC should provide guidance on the methods tenant screening companies can use to make explanations. Regulators should consider the value of Shapley values. The SHAP approach has been validated by peer review.[83] To underscore its credibility, it is worth mentioning that its creator received a Nobel Prize in mathematics for the contribution made by SHAP to game theory. SHAP values have the additional benefit of providing answers on a per-output basis.[84] An output can provide an explanation for each applicant, even when a system uses dynamic models. Because of this flexibility, a SHAP test holds the additional value of helping reviewers to identify which is leading to disparate impacts.

III. Anti-discrimination and Fairness in Tenant Screening: Recommendations on Enforcement

A. Section 5 of the FTC Act

The Federal Trade Commission Act (FTCA) prohibits “‘unfair or deceptive acts or practices’ in interstate commerce.”[85] More specifically, Section 5 of the FTCA endows the FTC with “broad and flexible authority to take action against practices that harm consumers.”[86] The FTC should prohibit use of rental screening criteria that cannot be shown to have a reliable and significant predictive effect, in particular in the context of criminal records and evictions. We support the analysis of the Shriver Center on Poverty Law, National Low Income Housing Coalition, and Re-entry & Housing Working Group that the FTC should use this authority to prevent the overuse of criminal records in the housing context. Further, the FTC should require landlords to evaluate evictions on a case-by-case basis, when used at all, so that prior evictions with mitigating circumstances do not limit the ability to access rental housing.[87] In the case of households using housing vouchers, housing providers and screening services should face consequences for failing to adequately consider vouchers as a steady source of income and future rental payments.

Section 5 states that a practice is unfair if it causes “substantial injury,” is not “reasonably avoidable” by the consumer, and it is not outweighed by “countervailing benefits” to consumers or to competition.[88] Any algorithm or other tenant screening system that has disparate impacts against protected classes should meet the unfairness standard. Discrimination is inherently unfair; it leads to harms, members of protected classes cannot do anything to remedy it, and it does not serve a countervailing benefit to competition or enhance consumer welfare.

B. Algorithmic Audits

An algorithmic audit would assess a tenant screening service for how ensures that it protects consumers from unfair deceptive acts and practices and protected classes from discriminatory activities. Service providers that create algorithmic tenant screening models should be held accountable when they use data that is known to be inaccurate. The FTC should use its enforcement authority to provide remedies from consumers when such a model continues to use incorrect data if it subsequently leads to adverse effects.

The FTC must require algorithmic tenant screening companies to put resources into responding to consumer disputes and to conduct analyses of PPD providers on an ongoing basis to ensure that those providers have systems in place to ensure the accuracy of their data. Systems should include processes to allow tenants to review their records and correct them when they are inaccurate.

To facilitate the process, the FTC and the CFPB should provide oversight and guidance on how to assess disparate impacts from algorithmic tenant screening services and clarify when providers should find LDAs. As a tool of enforcement, auditors should collect random samples of rejected applications to review real-world outcomes.

C. Fair Credit Reporting Act (FCRA)

We support the National Consumer Law Center’s (NCLC) call for the CFPB to use its FCRA regulatory powers to ensure accuracy in credit and consumer reporting. [89] For example, the CFPB should requiring credit bureaus and other credit reporting agencies to use stricter criteria to match consumer information with the consumer, such as matching a consumer’s entire social security number.[90] Doing so can prevent consumers with the same name from being confused for each other. It can further minimize errors in consumer reporting by requiring background screening companies to verify the records they obtained by locating the records’ original source.[91]

We similarly support the Partnership for Housing Justice, the Shriver Center for Poverty Law, the National Low Income Housing Coalition, and the Reentry & Housing Working Group’s call for the CFPB to use its full authority under FCRA to regulate tenant screening so that harmful information obtained in the tenant screening process is not used against prospective renters.[92] As mentioned in the Shriver Center on Poverty Law’s letter to the CFPB, there may be inaccuracies in criminal records, eviction records, and other consumer information.[93] The CFPB should regulate screening to prevent these inaccuracies from having an overwhelmingly negative impact on renters (and disproportionately on Black and Brown renters).

D. Fair Housing Act Violations

As noted above, tenant screening practices may constitute disparate treatment or disparate impact discrimination on the basis of characteristics protected by the Fair Housing Act. We encourage the FTC and CFPB to engage in heightened monitoring of potential housing discrimination in the context of tenant screening practices, such as the use of criminal records, eviction records, and other criteria in ways that have discriminatory outcomes or where such data is applied differently on the basis of race or other protected characteristics. We recommend that the FTC and CFPB formally coordinate with HUD and DOJ to advance fair housing enforcement in this context, for example by referring fair housing violations and by coordinating on the use of respective UDAP and Fair Housing Act authority. The agencies should consider entering a Memorandum of Understanding to coordinate enforcement responsibilities and to maximize enforcement impact. We also recommend that the agencies explore ways to support source of income anti-discrimination protections where those exist at a state or local level, or to indicate for HUD where source of income discrimination may be a proxy for Fair Housing Act discrimination.

Thank you for your work on these important issues and for your consideration of our recommendations. For further discussion, please contact Nichole Nelson, Senior Policy Advisor, at nnelson@ncrc.org or Adam Rust, Senior Policy Advisor, at arust@ncrc.org.

Best regards,

Jesse Van Tol

President and Chief Executive Officer

National Community Reinvestment Coalition

[1] Wonyoung So, “Which Information Matters? Measuring Landlord Assessment of Tenant Screening Reports,” Housing Policy Debate, August 30, 2022, 5 and 18-19, https://doi.org/10.1080/10511482.2022.2113815 and U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, “Office of General Counsel Guidance on Application of Fair Housing Act Standards to the Use of Criminal Records by Providers of Housing and Real Estate-Related Transactions,” April 4, 2016, 4-5, https://www.hud.gov/sites/documents/HUD_OGCGUIDAPPFHASTANDCR.PDF.

[2] Anna Resoti, “‘We Go Totally Subjective’ : Discretion, Discrimination, and Tenant Screening in a Landlord’s Market,” Law & Social Inquiry, 45, no. 3, August 2020, 627, https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/law-and-social-inquiry/article/we-go-totally-subjective-discretion-discrimination-and-tenant-screening-in-a-landlords-market/1AABF71AEA176ADA1F8D93E7C424C4D2/share/3f4060bf42159f964bbd50055a9db16a78f9789a#pf24.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Ibid.;

U.S. Census Bureau, Table B25064: Median Gross Rent (Dollars), 2010: ACS 5-Year Estimates, Detailed Tables, United States,

https://data.census.gov/table?q=B25064:+MEDIAN+GROSS+RENT+(DOLLARS)&tid=ACSDT5Y2010.B25064; U.S. Census Bureau, Table B25064: Median Gross Rent (Dollars), 2011: ACS 5-Year Estimates, Detailed Tables, United States,

https://data.census.gov/table?q=B25064:+MEDIAN+GROSS+RENT+(DOLLARS)&tid=ACSDT5Y2011.B25064; U.S. Census Bureau, Table B25064: Median Gross Rent (Dollars), 2012: ACS 5-Year Estimates, Detailed Tables, United States,

https://data.census.gov/table?q=B25064:+MEDIAN+GROSS+RENT+(DOLLARS)&tid=ACSDT5Y2012.B25064; U.S. Census Bureau, Table B25064: Median Gross Rent (Dollars), 2013: ACS 5-Year Estimates, Detailed Tables, United States,

https://data.census.gov/table?q=B25064:+MEDIAN+GROSS+RENT+(DOLLARS)&tid=ACSDT5Y2013.B25064; U.S. Census Bureau, Table B25064: Median Gross Rent (Dollars), 2014: ACS 5-Year Estimates, Detailed Tables, United States,

https://data.census.gov/table?q=B25064:+MEDIAN+GROSS+RENT+(DOLLARS)&tid=ACSDT5Y2014.B25064; U.S. Census Bureau, Table B25064: Median Gross Rent (Dollars), 2015: ACS 5-Year Estimates, Detailed Tables, United States,

https://data.census.gov/table?q=B25064:+MEDIAN+GROSS+RENT+(DOLLARS)&tid=ACSDT5YAIAN2015.B25064; U.S. Census Bureau, Table B25064: Median Gross Rent (Dollars), 2016: ACS 5-Year Estimates, Detailed Tables, United States,

https://data.census.gov/table?q=B25064:+MEDIAN+GROSS+RENT+(DOLLARS)&tid=ACSDT5Y2016.B25064; U.S. Census Bureau, Table B25064: Median Gross Rent (Dollars), 2017: ACS 5-Year Estimates, Detailed Tables, United States,

https://data.census.gov/table?q=B25064:+MEDIAN+GROSS+RENT+(DOLLARS)&tid=ACSDT5Y2017.B25064; U.S. Census Bureau, Table B25064: Median Gross Rent (Dollars), 2018: ACS 5-Year Estimates, Detailed Tables, United States,

https://data.census.gov/table?q=B25064:+MEDIAN+GROSS+RENT+(DOLLARS)&tid=ACSDT5Y2018.B25064; U.S. Census Bureau, Table B25064: Median Gross Rent (Dollars), 2019: ACS 5-Year Estimates, Detailed Tables, United States,

https://data.census.gov/table?q=B25064:+MEDIAN+GROSS+RENT+(DOLLARS)&tid=ACSDT5Y2019.B25064; and U.S. Census Bureau, Table B25064: Median Gross Rent (Dollars), 2021: ACS 5-Year Estimates, Detailed Tables, United States,

https://data.census.gov/table?q=B25064:+MEDIAN+GROSS+RENT+(DOLLARS)&tid=ACSDT5Y2021.B25064.

[5] Ashfaq Khan, Christian E. Weller, and Lily Roberts, “The Rental Housing Crisis Is a Supply Problem That Needs Supply Solutions,” The Center for American Progress, August 22, 2022, https://www.americanprogress.org/article/the-rental-housing-crisis-is-a-supply-problem-that-needs-supply-solutions.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Resoti, “‘We Go Totally Subjective,’” 627;

U.S. Census Bureau, Table B25064: Median Gross Rent (Dollars), 2010: ACS 5-Year Estimates, Detailed Tables, United States,

https://data.census.gov/table?q=B25064:+MEDIAN+GROSS+RENT+(DOLLARS)&tid=ACSDT5Y2010.B25064; U.S. Census Bureau, Table B25064: Median Gross Rent (Dollars), 2011: ACS 5-Year Estimates, Detailed Tables, United States,

https://data.census.gov/table?q=B25064:+MEDIAN+GROSS+RENT+(DOLLARS)&tid=ACSDT5Y2011.B25064; U.S. Census Bureau, Table B25064: Median Gross Rent (Dollars), 2012: ACS 5-Year Estimates, Detailed Tables, United States,

https://data.census.gov/table?q=B25064:+MEDIAN+GROSS+RENT+(DOLLARS)&tid=ACSDT5Y2012.B25064; U.S. Census Bureau, Table B25064: Median Gross Rent (Dollars), 2013: ACS 5-Year Estimates, Detailed Tables, United States,

https://data.census.gov/table?q=B25064:+MEDIAN+GROSS+RENT+(DOLLARS)&tid=ACSDT5Y2013.B25064; U.S. Census Bureau, Table B25064: Median Gross Rent (Dollars), 2014: ACS 5-Year Estimates, Detailed Tables, United States,

https://data.census.gov/table?q=B25064:+MEDIAN+GROSS+RENT+(DOLLARS)&tid=ACSDT5Y2014.B25064;

U.S. Census Bureau, Table B25064: Median Gross Rent (Dollars), 2015: ACS 5-Year Estimates, Detailed Tables, United States,

https://data.census.gov/table?q=B25064:+MEDIAN+GROSS+RENT+(DOLLARS)&tid=ACSDT5YAIAN2015.B25064;

U.S. Census Bureau, Table B25064: Median Gross Rent (Dollars), 2016: ACS 5-Year Estimates, Detailed Tables, United States,

https://data.census.gov/table?q=B25064:+MEDIAN+GROSS+RENT+(DOLLARS)&tid=ACSDT5Y2016.B25064; U.S. Census Bureau, Table B25064: Median Gross Rent (Dollars), 2017: ACS 5-Year Estimates, Detailed Tables, United States,

https://data.census.gov/table?q=B25064:+MEDIAN+GROSS+RENT+(DOLLARS)&tid=ACSDT5Y2017.B25064; U.S. Census Bureau, Table B25064: Median Gross Rent (Dollars), 2018: ACS 5-Year Estimates, Detailed Tables, United States,

https://data.census.gov/table?q=B25064:+MEDIAN+GROSS+RENT+(DOLLARS)&tid=ACSDT5Y2018.B25064; U.S. Census Bureau, Table B25064: Median Gross Rent (Dollars), 2019: ACS 5-Year Estimates, Detailed Tables, United States,

https://data.census.gov/table?q=B25064:+MEDIAN+GROSS+RENT+(DOLLARS)&tid=ACSDT5Y2019.B25064; and U.S. Census Bureau, Table B25064: Median Gross Rent (Dollars), 2021: ACS 5-Year Estimates, Detailed Tables, United States,

https://data.census.gov/table?q=B25064:+MEDIAN+GROSS+RENT+(DOLLARS)&tid=ACSDT5Y2021.B25064.

[9] Joint Center for Housing Studies of Harvard University, “America’s Rental Housing,” 2022, 1, https://www.jchs.harvard.edu/sites/default/files/reports/files/Harvard_JCHS_Americas_Rental_Housing_2022.pdf.

[10] Ibid.

[11] Ibid., 10-11.

[12] So, “Which Information Matters?” 5 and 22.

[13] Ibid., 6.

[14] Ibid.

[15] U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, “Office of General Counsel Guidance on Application of Fair Housing Act Standards to the Use of Criminal Records,” April 4, 2016, 2.

[16] Ashley Nellis, “The Color of Justice: Racial and Ethnic Disparity in State Prisons,” The Sentencing Project, 2021, 6, https://www.sentencingproject.org/app/uploads/2022/08/The-Color-of-Justice-Racial-and-Ethnic-Disparity-in-State-Prisons.pdf.

[17] U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, “Office of General Counsel Guidance on Application of Fair Housing Act Standards to the Use of Criminal Records,” April 4, 2016, 2, 3, and 8 and U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, “Implementation of the Office of General Counsel’s Guidance on Application of Fair Housing Act Standards to the Use of Criminal Records by Providers of Housing and Real Estate-Related Transactions,” June 10, 2022, 4 and 10, https://www.hud.gov/sites/dfiles/FHEO/documents/Implementation%20of%20OGC%20Guidance%20on%20Application%20of%20FHA%20Standards%20to%20the%20Use%20of%20Criminal%20Records%20-%20June%2010%202022.pdf.

[18] U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, “Office of General Counsel Guidance on Application of Fair Housing Act Standards to the Use of Criminal Records,” April 4, 2016, 2 and 8 and U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, “Implementation of the Office of General Counsel’s Guidance on Application of Fair Housing Act Standards to the Use of Criminal Records,” June 10, 2022, 4 and 10.

[19] Ibid.

[20] U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, “Office of General Counsel Guidance on Application of Fair Housing Act Standards to the Use of Criminal Records,” April 4, 2016, 8 and U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, “Implementation of the Office of General Counsel’s Guidance on Application of Fair Housing Act Standards to the Use of Criminal Records,” June 10, 2022, 4 and 10.

[21] U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, “Office of General Counsel Guidance on Application of Fair Housing Act Standards to the Use of Criminal Records,” April 4, 2016, 2 and U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, “Implementation of the Office of General Counsel’s Guidance on Application of Fair Housing Act Standards to the Use of Criminal Records,” June 10, 2022, 4.

[22] U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, “Office of General Counsel Guidance on Application of Fair Housing Act Standards to the Use of Criminal Records,” April 4, 2016, 6.

[23] Ibid.

[24] Equal Rights Center, “Unlocking Discrimination: A DC Area Testing Investigation About Racial Discrimination and Criminal Records Screening Policies in Housing,” 2016, 16, https://equalrightscenter.org/wp-content/uploads/unlocking-discrimination-web.pdf.

[25] Ibid.4,6, and 20.

[26] Greater New Orleans Housing Action Center, “Locked Out: Criminal Background Checks as a Tool for Discrimination,” 3-4, https://lafairhousing.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/Criminal_Background_Audit_FINAL.pdf.

[27] Ibid., 4, 17, and 18.

[28] Ibid., 4 and 18.

[29] Ibid., 4.

[30] Ibid., 4 and 18.

[31] Ibid. 4, 18, and 20.

[32] Ibid., 19, 21-22, and 25.

[33] Ibid., 4, 18, and 22.

[34] Tim Robustelli, Yuliya Panfil, Katie Oran, Chenab Navalkha, and Emily Yelverton, “Displaced in America,” New America, Executive Summary, https://www.newamerica.org/future-land-housing/reports/displaced-america/executive-summary.

[35] Peter Hepburn, Renee Louis, and Matthew Desmond, “Racial and Gender Disparities Among Evicted Americans,” Sociological Science, 7, 2020, 649, https://sociologicalscience.com/download/vol-7/december/SocSci_v7_649to662.pdf.

[36] Ibid., 649, 650, and 654-655.

[37] Ibid., 658.

[38] Camila Vallejo, Jacob Haas, and Peter Hepburn, “Preliminary Analysis: Eviction Filing Patterns in 2022,” The Eviction Lab, March 9, 2023, https://evictionlab.org/ets-report-2022/ and Peter Hepburn, Olivia Jin, Joe Fish, Emily Lemmerman, Anne Kat Alexander, and Matthew Desmond, “Preliminary Analysis: Eviction Filing Patterns in 2021,” The Eviction Lab, March 8, 2022, https://evictionlab.org/us-eviction-filing-patterns-2021/.

[39] May 12, 2023 e-mail from Peter Hepburn, Statistician and Quantitative Analyst Role, The Eviction Lab, Princeton University.

[40] Ibid.

[41] Vallejo, Haas, and Hepburn, “Preliminary Analysis: Eviction Filing Patterns in 2022.”

[42] May 12, 2023 e-mail from Peter Hepburn, Statistician and Quantitative Analyst Role, The Eviction Lab, Princeton University.

[43] So, “Which Information Matters?” 17-18.

[44] Matthew Desmond, Evicted: Poverty and Profit in the American City, (New York, NY: Penguin Random House, 2016), 68.

[45]So, “Which Information Matters?” 5. “Using housing court histories to make rental decisions penalizes tenants who were previously involved in an eviction case from obtaining future housing even if an eviction case is dismissed or the tenant prevails.”

[46] So, “Which Information Matters?” 7.

[47] Ibid.,17-18.

[48] National Consumer Law Center, “Past Imperfect: How Credit Scores and Other Analytics ‘Bake In’ and Perpetuate Past Discrimination,” May 2016, 1-2, https://www.nclc.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/09/Past_Imperfect.pdf.

[49] Ibid., 2 and Natalie Campisi, “From Inherent Racial Bias to Incorrect Data—The Problems With Current Credit Scoring Models,” Forbes Advisor, February 26, 2021, https://www.forbes.com/advisor/credit-cards/from-inherent-racial-bias-to-incorrect-data-the-problems-with-current-credit-scoring-models/.

[50] National Consumer Law Center, “Past Imperfect,” 2.

[51] Ibid.

[52] Ibid., 5 and Woodstock Institute, “Bridging the Gap: Credit Scores and Economic Opportunity in Illinois Communities of Color,” September 2010, 4, https://woodstockinst.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/05/bridgingthegapcreditscores_sept2010_smithduda.pdf.

[53] Woodstock Institute, “Bridging the Gap,” 4-5 and National Consumer Law Center, “Past Imperfect,” 5.

[54] Ibid.

[55] National Consumer Law Center, “Past Imperfect,” 5.

[56] Woodstock Institute, “Bridging the Gap,” 4-5 and National Consumer Law Center, “Past Imperfect,” 5.

[57] National Consumer Law Center, “Past Imperfect,” 6 and Raphael W. Bostic, Paul S. Calem, and Susan M. Wachter, “Hitting the Wall: Credit as an Impediment to Homeownership,” Joint Center for Housing Studies, February 2004, 18, https://www.jchs.harvard.edu/sites/default/files/media/imp/babc_04-5.pdf.

[58] Campisi, “From Inherent Racial Bias to Incorrect Data.”

[59] Ibid.

[60] Federal Trade Commission, “New FTC Data Show Consumers Reported Losing Nearly $8.8 Billion to Scams in 2022,” February 23, 2023, https://www.ftc.gov/news-events/news/press-releases/2023/02/new-ftc-data-show-consumers-reported-losing-nearly-88-billion-scams-2022.

[61] Ibid.

[62] U.S. Department of Justice: Office of Justice Programs, “Identity Theft: Special Features,” https://www.ojp.gov/feature/identity-theft/overview and Chi Chi Wu, “Solving the Credit Conundrum” National Consumer Law Center, December 2013, 5, https://www.nclc.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/report-credit-conundrum-2013.pdf.

[63] Federal Trade Commission, “Equifax Data Breach Settlement,” December 2022, https://www.ftc.gov/enforcement/refunds/equifax-data-breach-settlement.

[64] Ibid.

[65] Ibid.

[66] National Housing Law Project, “Source of Income Discrimination,” November 17, 2017, https://www.nhlp.org/resources/source-of-income-discrimination-2/ and “Learn About the Protected Class of Source of Income,” Fair Housing Council of Oregon, https://fhco.org/learn-about-the-protected-class-of-source-of-income/.

[67] U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, “Housing Choice Vouchers Fact Sheet,” https://www.hud.gov/topics/housing_choice_voucher_program_section_8#hcv01; U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, Office of Inspector General, “Newark Landlords Agree to Pay $430,000 to Settle Allegations of Collecting Excess Rent in Sparrow Run,” May 2, 2022, https://www.hudoig.gov/newsroom/press-release/newark-landlords-agree-pay-430000-settle-allegations-collecting-excess-rent; and Kayla Canne, “‘We don't take that:’ Why illegal discrimination toward Section 8 tenants goes unchecked in NJ,” Asbury Park Press, October 25, 2021, https://www.app.com/in-depth/news/investigations/2021/10/26/section-8-nj-housing-choice-voucher-discrimination-law-new-jersey/5602044001/.

[68] Fannie Mae, “Housing Choice Voucher Program Explained,” 2022, https://multifamily.fanniemae.com/media/15531/display.

[69] The National Low Income Housing Coalition, “The Gap: A Shortage of Affordable Homes,” March 2023, 3, https://nlihc.org/sites/default/files/gap/Gap-Report_2023.pdf.

[70] Ibid., 9.

[71] Ibid., 19.

[72] U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, Office of Inspector General, “HUD OIG Announces Environmental Justice Initiative,” March 9, 2023,

https://www.hudoig.gov/newsroom/press-release/hud-oig-announces-environmental-justice-initiative.

[73] U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, Office of Inspector General, “Newark Landlords Agree to Pay $430,000.”

[74] Ibid.

[75] U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, Office of Inspector General, “Holyoke Landlord Agrees to $15,000 Settlement for False Claims Act Violations,” February 8, 2023, https://www.hudoig.gov/newsroom/press-release/holyoke-landlord-agrees-15000-settlement-false-claims-act-violations.

[76] U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, Office of Inspector General, “HUD OIG Announces Environmental Justice Initiative.”

[77] “Rent Payment History Offers Greater Predictability into Consumer Credit Performance,” TransUnion, 2021, https://www.globenewswire.com/news-release/2021/12/07/2347334/0/en/Rent-Payment-History-Offers-Greater-Predictability-into-Consumer-Credit-Performance.html. According to Steve Holden, Vice President of Single-Family Analytics at Fannie Mae, “TransUnion’s findings support Fannie Mae’s belief that if someone is paying rent consistently it’s likely they could pay their mortgage consistently, too.” Fannie Mae recently updated its automated underwriting system to incorporate rental payment history in the mortgage credit evaluation process.

[78] Kelly Thompson Cochran and Michael Stegman, “Utility, Telecommunications, and Rental Data in Underwriting Credit,” FinRegLab, https://finreglab.org/alternative-data-in-underwriting-credit/utility-telecommunications-and-rental-data-in-underwriting-credit/.

[79] Tenant Credit Checks, “Featured Services Offered,” TenantCreditChecksWordPress.com. Retrieved May 22, 2023, from https://tenantcreditchecks.wordpress.com/about/.

[80] Alex Engler, “The EU and U.S. Diverge on AI Regulation: A Transatlantic Comparison and Steps to Alignment,” Brookings Institution, https://www.brookings.edu/research/the-eu-and-us-diverge-on-ai-regulation-a-transatlantic-comparison-and-steps-to-alignment/.

[81] Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, “Adverse Action Tech Sprint,” https://www.consumerfinance.gov/rules-policy/competition-innovation/cfpb-tech-sprints/electronic-disclosures-tech-sprint/.

[82] Tenant Credit Checks, “Featured Services Offered,” Retrieved May 22, 2023.

[83] SHAP, “An Introduction to Explainable AI with Shapley Values—SHAP Latest Documentation [GitHub]. Retrieved May 22, 2023, from https://shap.readthedocs.io/en/latest/example_notebooks/overviews/An%20introduction%20to%20explainable%20AI%20with%20Shapley%20values.html.

[84] Ibid.

[85] Reentry & Housing Working Group, Eric Sirota, Shriver Center on Poverty Law, and Kim Johnson, National Low Income Housing Coalition, “Summary of Memorandum,” January 26, 2022, 9, https://sargentshriverc.sharepoint.com/advocacy/Shared%20Documents/Housing%20Rights/Criminal%20Records%20and%20Housing%20Work/Federal%20and%20National%20Work/FTC/Letters%20to%20FTC/PJH%20RFI%20Comment/Exhibit%20C%20-%20Section%205%20memo.pdf

[86] Ibid.

[87] Partnership for Housing Justice Letter to the Federal Trade Commission and Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, May 2023, 5-6, https://docs.google.com/document/d/1X57nGzlZI_iO3kfb5CFN7fntDJ3IMa0y9Tgrf_aTXbA/edit.

[88] Federal Reserve, “Federal Trade Commission Act Section 5: unfair or Deceptive Acts or Practices,” 7, https://www.federalreserve.gov/boarddocs/supmanual/cch/200806/ftca.pdf.

[89] National Consumer Law Center, “2023 Credit & Consumer Reporting Priorities to Promote Economic Stability,” January 18, 2023, https://www.nclc.org/resources/2023-credit-consumer-reporting-priorities-to-promote-economic-stability/.

[90] Ibid.

[91] Ibid.

[92] Partnership for Just Housing Letter to the Federal Trade Commission and the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, ”Response to Request for Information, Docket ID FTC-2023-0024,” 6-7; Shriver Center on Poverty Law Letter to the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, “Regulations and Guidance Regarding Criminal Records Tenant Screening Practices,” 3, https://www.povertylaw.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/Updated-FTC-Letter-with-all-Exhibdits_Final.pdf; and Reentry & Housing Working Group, Eric Sirota, Shriver Center on Poverty Law, and Kim Johnson, National Low Income Housing Coalition, “Summary of Memorandum,” 9.

[93] The Shriver Center on Poverty Law, “Regulations and Guidance Regarding Criminal Records Tenant Screening Practices,” 4, 6, and 10.