December 9, 2019

Ms. Kathy Kraninger

Director

Consumer Financial Protection Bureau

1700 G. St. NW

Washington DC, 20552

Dear Director Kraninger:

Widely available and accessible Home Mortgage Disclosure Act (HMDA) data has been instrumental to achieving the statutory purpose of HMDA of assessing whether lending institutions are serving the housing and credit needs of communities. NCRC, our members and allies are concerned that the CFPB is implementing public dissemination of HMDA data in a manner that thwarts its statutory purpose. In particular, the CFPB has stopped producing tables capturing lending trends to borrowers and neighborhoods that facilitated public use of HMDA data. The agency replaced these pre-formatted tables with raw data that only expert researchers can use. This choice greatly constrains the public availability and use of the data.

Prior to the CFPB’s assumption of HMDA data implementation, the Federal Reserve Board, on behalf of the Federal Financial Institutions Examination Council (FFIEC), provided detailed pre-formatted data tables to the general public regarding lending patterns by borrower and census tract demographics for individual lenders and for aggregate lending at the metropolitan statistical (MSA) level (regulation C refers to these tables as Disclosure Statements).

These tables facilitated use of HMDA data by stakeholders including local fair housing public sector officials, journalists and community groups that monitored fair lending and Community Reinvestment (CRA) performance of lending institutions. The pre-formatted tables did not require knowledge or purchase of expensive advanced statistical software for a member of the public to use. A member of the public did not even need to know how to use Excel, except that the Federal Reserve Board added an option of downloading the tables into Excel in recent years for those who wanted to use the tables in this manner.

Now, the CFPB has opted to disseminate the data in a manner that is primarily useful only to researchers with expertise of advanced statistics and software such as SAS or SPSS. The ordinary citizen cannot readily use the data that is disseminated by the CFPB. The loss in public accountability is immense. Journalists used the previous pre-formatted tables to write articles that grabbed the public’s attention and that motivated lending institutions to improve their fair lending and CRA performance, sometimes by partnering with the non-profit and public sectors. In addition, the pre-formatted tables facilitated community group input on CRA exams and merger applications, which are key mechanisms by which CRA and the bank merger laws work to mutually benefit lenders and the public at large.

By making it vastly more difficult to access HMDA data, the CFPB is undercutting the public accountability facilitated by HMDA, CRA, and the fair lending laws to the detriment of economic efficiency and equity. The widespread use of HMDA data helps stakeholders identify and voluntarily address racial and gender disparities. Now, significant disparities will probably have to await more formal regulatory rulemaking or enforcement proceedings, which is an inefficient outcome for an agency that is trying to achieve more market-based corrective outcomes.

As described in U.S. Code, Chapter Title 12, Chapter 29, §?2801 the statutory purpose of HMDA data is to:

provide the citizens and public officials of the United States with sufficient information to enable them to determine whether depository institutions are filling their obligations to serve the housing needs of the communities and neighborhoods in which they are located and to assist public officials in their determination of the distribution of public sector investments in a manner designed to improve the private investment environment.[1]

This purpose cannot be achieved if the data is disseminated in a manner to render it accessible only by few experts. For example, there is no reason why housing and community development staff of local government agencies should need to know how to use advanced statistical software to determine how demographic groups in their city fare in terms of their housing needs being met. By halting the publication of pre-formatted tables, the CFPB has effectively cut off thousands of local government agencies from using this data since they do not have the funds to either purchase advanced statistical software or contract with expert researchers.

To further illustrate the inconsistencies in the CFPB’s dissemination of the data, U.S. Code Title 12, Chapter 29, §?2809 (a) states that starting in 1980, for each MSA, the FFIEC shall produce tables showing:

…aggregate lending patterns for various categories of census tracts grouped according to location, age of housing stock, income level, and racial characteristics.[2]

The current CFPB tables do not provide summary data in pre-formatted tables for various categories of census tracts in a meaningful fashion to help stakeholders determine whether credit needs for different types of loans such as home purchase or refinance lending are being met.

In its manual for examiners, lending institutions and the general public, the FDIC expands upon the statutory requirement to provide aggregate lending data. The FDIC states:

…the FFIEC will use the annual data submitted pursuant to Regulation C to make available aggregated data for each MSA and MD, showing lending patterns by property location, age of housing stock, and income level, sex, ethnicity, and race.[3]

This description expands upon the 1975 statutory language to establish an expectation that summary, aggregate data will be presented in tables showing the data by demographic characteristics of borrowers in addition to census tracts. The new CFPB summary tables fail to show data for either groups of borrowers or census tracts that enable stakeholders to assess whether housing needs are being met.

The CFPB’s official interpretations of Regulation C implementing HMDA data furthers the public’s expectations that the data will be readily available in readable and summary tables. The CFPB’s interpretations provide suggested language for banks to use regarding how the public can access HMDA data and what data the public can expect to receive. The sample language states:

Home Mortgage Disclosure Act Notice: The HMDA data about our residential mortgage lending are available online for review. The data show geographic distribution of loans and applications; ethnicity, race, sex, age, and income of applicants and borrowers; and information about loan approvals and denials. These data are available online at the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau’s Web site (www.consumerfinance.gov/hmda). HMDA data for many other financial institutions are also available at this Web site.[4]

This notice clearly describes that HMDA data will be available on the CFPB website and will display summary information of lending patterns by demographics of borrowers as well as geographical distribution. It does not include disclaimers that only those members of the public that can use advanced statistical software will be able to access the data and create the relevant tables after hours of labor intensive work.

From 1999 through 2016, the Fed, through the FFIEC, had produced detailed pre-formatted tables consistent with the descriptions in Regulation C and the FDIC manual.[5] Our member organizations, some of whom had a recent phone call with your senior staff, had not only become accustomed to them but found them indispensable to their CRA and fair lending advocacy. With access to these tables abruptly cut-off, there is no readily available substitutes. Therefore, input on CRA exams, merger applications, and local credit needs assessments of public agencies will decrease precipitously. The pre-formatted tables had become a key part of the implementation of HMDA’s statutory purposes of public education and input. Their sudden cancellation is a chilling blow to the effectiveness of the law and implementing regulations.

The termination of the pre-formatted tables is also inconsistent with the practices of other federal agencies in the dissemination of data. For example, the Census Bureau’s website produces hundreds of easy-to-use tables on demographics and economic conditions for geographical areas ranging from cities, counties, metropolitan areas to states. The democratic importance of the Census Bureau’s data dissemination is that it helps provide an informed citizenry that is better able to participate in decision-making at all levels in civic and public sector arenas. Likewise, HMDA data’s purpose is to produce more efficient and equitable lending markets through the use of data by a wide swath of the public. Restricting the dissemination of data to complicated downloads of raw data requiring sophisticated software defeats the democratic intent of HMDA and will contribute to producing lending markets that do not function well.

The HMDA data dissemination technique chosen by the CFPB may not in the long run reduce costs as much as the CFPB thinks. The agency will still be producing a significant number of pre-formatted tables but the tables produced will not be useful in identifying whether housing needs are being met in contrast to the previous tables. For modestly more costs, the agency could have retained a core number of the previous tables that would have avoided eviscerating the effectiveness of HMDA.

We heard from CFPB staff that the pre-formatted tables were not heavily used, but this type of assertion could probably be made regarding Census tables or any other publicly available dataset produced in a country with hundreds of millions of residents. Table usage cannot be measured like a commercial endeavor such as deciding whether to cancel a TV show because viewership is down. Even episodic or occasional use of the tables can have a profound impact in a particular market(s) or geographical area(s) if it is part of effective journalism or public comments on a merger application or CRA exam. The purpose of public data dissemination is to provide the tools for citizens to be thoughtfully engaged in public input forums that are required by law and that often result in more equitable solutions being devised. Viewed with this perspective, the benefits of accessible data dissemination vastly overwhelms its costs.

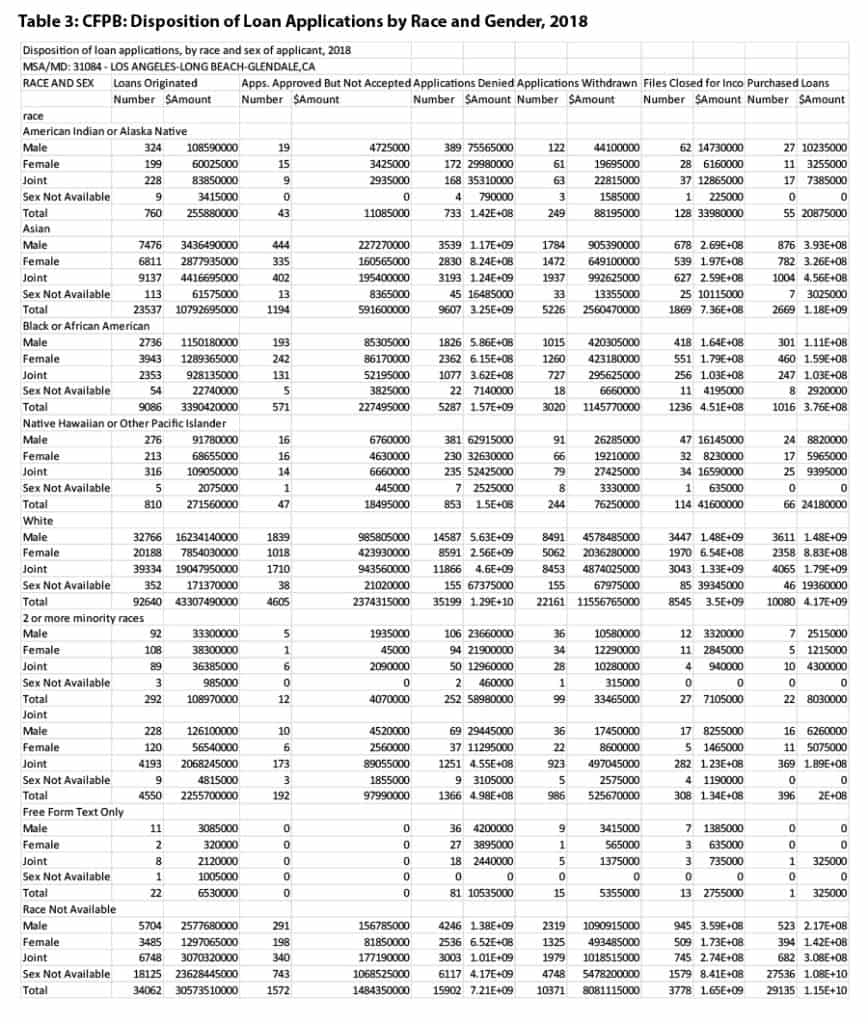

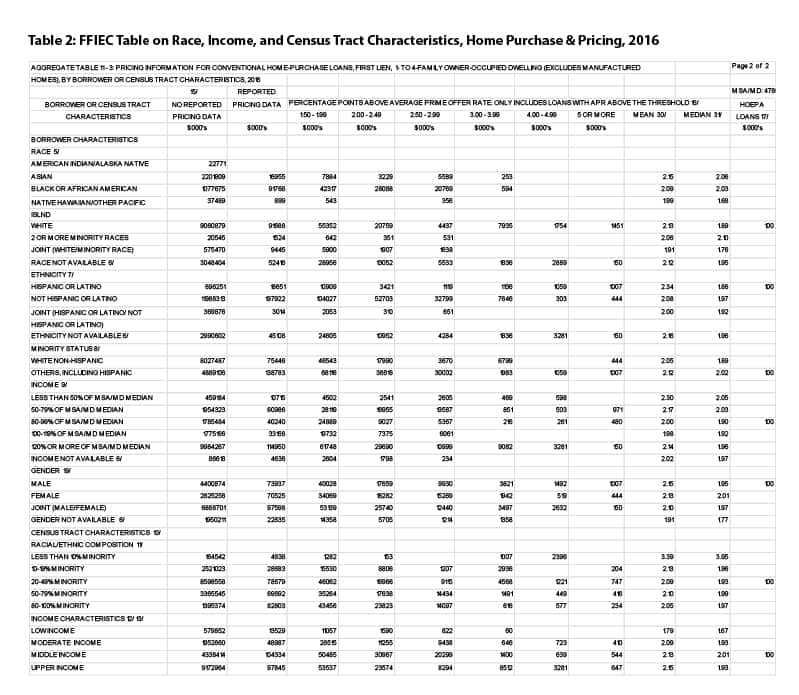

The tables in the appendix to this letter show clearly how the level of detail has decreased to such an extent from the previous FFIEC tables to the CFPB tables that the CFPB is not fulfilling the statutory and regulatory mandates to provide meaningful tables. Table 1 shows an FFIEC table using data from 2016 on refinance lending on a metropolitan level. The table shows applications received, loans made, applications denied and other actions on applications by ethnicity, gender and income of borrowers. The table has both loan counts and dollar amounts. The table is available in either PDF or Excel format.

Table 2 is an FFIEC table that describes loan pricing for home purchase, conventional, first lien loans, showing both prime loans and loans that are generally considered high cost that are 1.5 percentage points or greater than the average prime offer rate. The data is available by race, gender, income level of borrower and by census tract categories. This table is also available as a PDF or in Excel. Tables 1 and 2 and several others from the FFIEC website are available for the aggregate (all loans in a MSA) or for each lending institution reporting HMDA data.

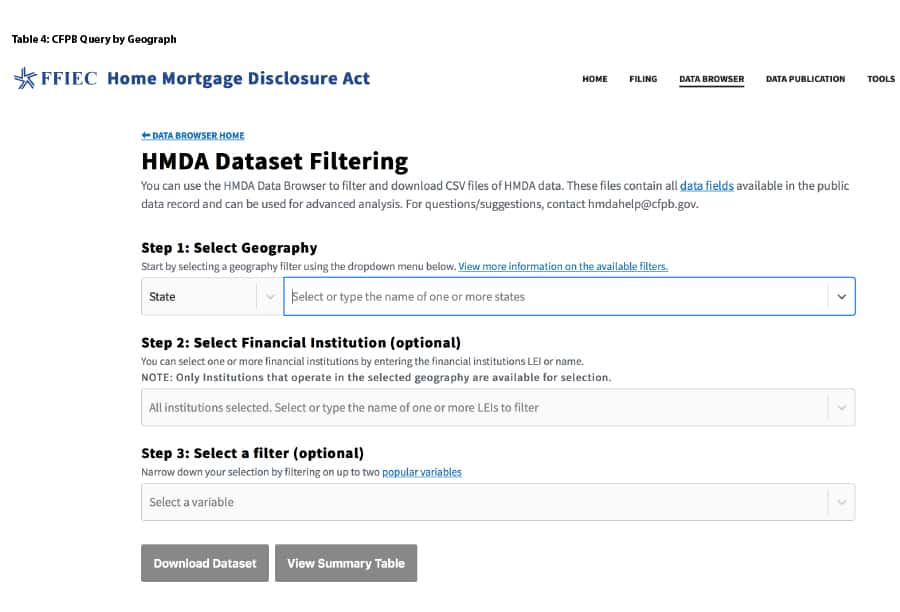

The contrast in detail jumps out when looking at Table 3 which is a new CFPB table on disposition of loan applications by race and gender for metropolitan areas.[6] While this may look similar to Tables 1 and 2, the profound difference is that this CFPB table lumps loan purposes and types together. It is therefore impossible for a user to determine whether lenders in the area are addressing the needs for home purchase lending as opposed to refinance or home improvement lending. By not separating out loan types and purposes, the table per se violates the statutory and regulatory intent of assessing whether needs are met for different groups of borrowers and census tracts. Moreover, this summary table is not available for individual lenders. The only “summary table” available for lenders is a table that describes the disposition of applications for each and every census tract in a metropolitan area.[7] This table is unusable for a member of the public that lacks sophisticated software for data analysis.

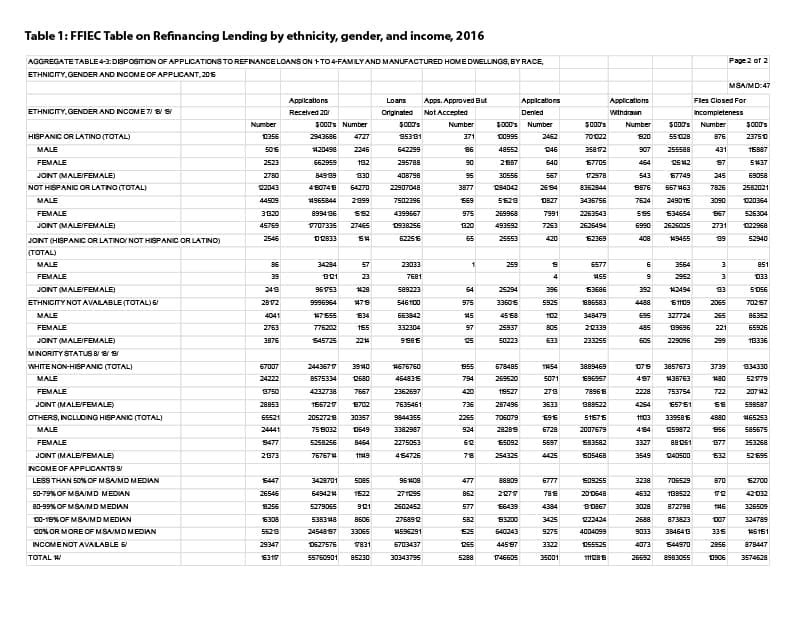

Finally, Table 4 displays a query engine on the CFPB website.[8] The query can produce results for only two variables at a time such as loan purpose and race. It also has only eleven of the variables in the HMDA dataset. A user can find out how many conventional home purchase loans there are in his or her MSA, but the user will be unable to reproduce Tables 1 and 2, which are the previous FFIEC tables. The query engine is not a useful substitute of the FFIEC tables.

Over the past year, NCRC and our members have suggested a number of possible remedies to your staff. We even proposed some cuts to the number of FFIEC pre-formatted tables while preserving essential ones. We suggested making the query engine more robust so that it could substitute for some or many of the FFIEC tables. We were also not expecting that the pre-formatted tables could immediately accommodate all the new Dodd Frank variables. It was most important to retain the core of what was previously available while working towards additional tables that could capture at least some of the new and important variables. However, none of our suggestions were implemented. The result is now a HMDA dissemination method that is not consistent with statutory purposes and intent.

Since our previous attempts did not work to save the pre-formatted tables, we are now suggesting that you propose new tables and then hold a public comment period on proposed changes. That would be the fairest way to solicit input from all stakeholders and members of the public and is also the required technique for changing a regulation that implements a statutory mandate.

We look forward to your reply. I cannot emphasize enough the importance of this issue. Please contact me or Josh Silver, Senior Advisor, on 202-628-8866.

Sincerely,

Jesse Van Tol

CEO

Organizations in support

National

Americans for Financial Reform Education Fund

Consumer Action

Friends of the African Union

NAACP

National NeighborWorks Association

Prosperity Now

The Africa Diaspora Directory

Alabama

Alabama Small Business Development Initiative

Birmingham Business Resource Center

Birmingham City Wide

Building Alabama Reinvestment

Community Action Association of Alabama

Community Action Partnership of North Alabama

Fair Housing Center of Northern Alabama

NAACP Economic Dev

Organized Community Action Program, Inc.

California

California Reinvestment Coalition

CAARMA Consumer Advocates Against Reverse Mortgage Abuse

cashcommunitydevelopment.org

CDC Small Business Finance

Peoples’ Self-Help Housing

Delaware

Delaware Community Reinvestment Action Council, Inc.

Florida

Community Enterprise Investments, Inc.

Veterans Center

Georgia

Georgia Advancing Communities Together, Inc.

The D&E Group

Hawaii

Hawai’i Alliance for Community-Based Economic Development

Illinois

Chicago Community Loan Fund

Housing Action Illinois

Illinois People’s Action

The Resurrection Project

Universal Housing Solutions CDC

Woodstock Institute

Indiana

Continuum of Care Network NWI, Inc..

Northwest Indiana Reinvestment Alliance

Louisiana

HousingLOUISIANA

Maryland

Housing Options & Planning Enterprises, Inc.

Maryland Consumer Rights Coalition

Network for Developing Conscious Communities

Massachusetts

Community Service Network Inc.

MA Affordable Housing Alliance

Plymouth Redevelopment Authority

Minnesota

African Career and Education Resource, Inc

Bii Gii Wiin CDLF

Jewish Community Action

Metropolitan Consortium of Community Developers

Missouri

Old North St. Louis Restoration Group

Montana

Montana Fair Housing

New York

Empire Justice Center

Fair Finance Watch / Inner City Press

North Carolina

Community Link

Durham Committee on the Affairs of Black People

Rebuild Communities NC

Reinvestment Partners

S J Adams Consulting

Ohio

Black Wall Street Cooperative

Cincinnati Branch NAACP

Homes on the Hill, CDC

Home Repair Resource Center

Ohio Fair Lending

Nazareth Housing Dev. Corp.

Oregon

CASA of Oregon

Portland Housing Center

Pennsylvania

Community Action Committee of the Lehigh Valley

Pittsburgh Community Reinvestment Group

Rhode Island

HousingWorks RI

Texas

Harlingen CDC

Washington

Northwest Fair Housing Alliance

West Virginia

Mountain State Justice

Wisconsin

Havenwoods EDC

Martin Drive NA

Metropolitan Milwaukee Fair Housing Council

NAACP Milwaukee Branch

Pathfinders Milwaukee, Inc.

Riverworks Development Corporation

SecureFutures

Urban Economic Development Association of Wisconsin (UEDA)

WI Democratic Latino Caucus

Wisconsin Faith Voices for Justice

Wisconsin Preservation Fund

YWCA Southeast Wisconsin

Appendix Tables

Table 1: FFIEC Table on Refinancing Lending by ethnicity, gender, and income, 2016

Table 2: FFIEC Table on Race, Income, and Census Tract Characteristics, Home Purchase & Pricing, 2016

Table 3: CFPB: Disposition of Loan Applications by Race and Gender, 2018

Table 4: CFPB Query by Geography

[1] See https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/12/2801

[2] See https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/12/2809

[3] See a section D, V–9.14 FDIC Consumer Compliance Examination Manual — June 2019, https://www.fdic.gov/regulations/compliance/manual/5/v-9.1.pdf

[4] Supplement I to Part 1003, Official Interpretations, Comment for 1003.5 – Disclosure and reporting, https://www.consumerfinance.gov/policy-compliance/rulemaking/regulations/1003/2019-01-01/Interp-5/

[5] See for detailed tables for each lending institution from 1999 through 2016, https://www.ffiec.gov/hmdaadwebreport/DisWelcome.aspx

[6] See https://ffiec.cfpb.gov/data-publication/aggregate-reports/2018

[7] See https://ffiec.cfpb.gov/data-publication/disclosure-reports/2018

[8] See https://ffiec.cfpb.gov/data-browser/data/2018?msamds=11500