This is one in a series of essays accompanying NCRC’s 2020 analysis that showed more chronic disease and greater risks from COVID-19 in formerly redlined communities. The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views or policy positions of NCRC.

Thousands of Black and White protesters got a taste recently of what it is like to feel the agony of being gassed by the police. It was painful, sickening and scary.

But citizens in western Louisville are regularly “gassed,” causing long-term health problems. The mayor’s own office admits this truth, with people dying an average of 10 years earlier in western Louisville compared to the rest of the city. In some neighborhoods, the life span is less than in war-torn Iraq according to Louisville’s Health Department.

In other words, 60,000 folks (enough to fill Cardinal Stadium) are dying prematurely and most of them are African Americans. As you address “systemic racism” in Louisville look at pollution in Black neighborhoods and the institutions that profit from it. Western Louisville’s air, water and soil are so toxic and rank among the worst of any American city. It is unlivable for a modern American neighborhood.

Louisville has the highest levels of pollution among the hundreds of midsize American cities. What does this mean in terms of our health, sustainability, safety and prosperity? In short, local residents are more vulnerable to a host of health problems and educational challenges. Neighborhood quality also is upended with 5,000 abandoned homes.

How do we know that Louisville has the worst air quality of any midsize city? The EPA provides the most valid and reliable measures of poor air quality. Our research pre-published in Lancet found that Louisville ranks No. 1 when you average out the four EPA measures of pollution in our analysis of air quality in 146 similarly sized cities.

Residents in neighborhoods near the industries are twice as likely to have either asthma or high blood pressure, four times more likely to have COPD, seven times more likely to have heart disease; and four times more likely to have poor physical health. Scientists widely agree that pollution is a major cause of these medical problems. Maybe, “staying in place” is not such a good idea if you live in western Louisville, especially when doctors are now telling patients to get out of the area whether for housing, work, school or worship.

Pollution does not only result in significantly lower life expectancy, but also results in other issues found in dozens of scientific journal articles including:

- Higher risks of fetal damage; miscarriages; dementia; cancer; asthma; lower birth rate; depression, and COVID-19.

- A host of community ills such as lower school achievement scores; reduced chances of college admission; higher chances of home foreclosure; higher crime rates; greater greenhouse gasses/climate change; significant reduction in homeowner’s equity and appreciation; reduced taxes to support essential neighborhood services; and unwalkable neighborhoods.

When Mayor Greg Fischer convened an elite task force (academic experts were ignored), they blamed it on the lifestyle of the poor: smoking, drinking, diet, obesity and education. Environmental degradation was not listed as a cause for reduced life expectancy.

This “blame the victim” explanation has been debunked by social scientists. This is evident in comparing cities with different levels of pollution. Examining the bottom income quartile of Louisville citizens at the age at which they passed compared with similar residents of the five cleanest cities that heavily regulated air pollution, poor men in Louisville died five years earlier and poor women died four years earlier than their counterparts in the cleaner cities. Poor people do live shorter lives, but they live longer in nonpolluted cities.

More interesting is that if you look at the top income quartile of the rich in dirty cities, they live the same number of years as their counterparts in clean cities. Why? Because the rich move far away from these poisonous polluters. Poor air quality is not an issue for the rich and powerful to fight — they live, work and go to school many miles from these polluters. In fact, many profit from it as they own these polluting industries.

Western Louisville faces an even bleaker future, with President Donald Trump recently killing 95 environmental regulations to keep air, water and soil nontoxic. Moreover, the pollluters lobbied the University of Louisville to close down both the Kentucky Institute for Environment and Sustainable Development as well as the Center for Sustainable Urban Neighborhoods.

Despite having a legislative mandate, the university agreed to scrub $3.5 million worth of federally funded research reports from the website and pushed the center off campus to Washington D.C.

The call for greater equity also means cleaning up the air, water and soil. Poor people needlessly suffer more here than the same low-income people in West Coast cites. If we adopted the same tough, environmental regulations as our West Coast counterparts, western Louisville would surely bloom.

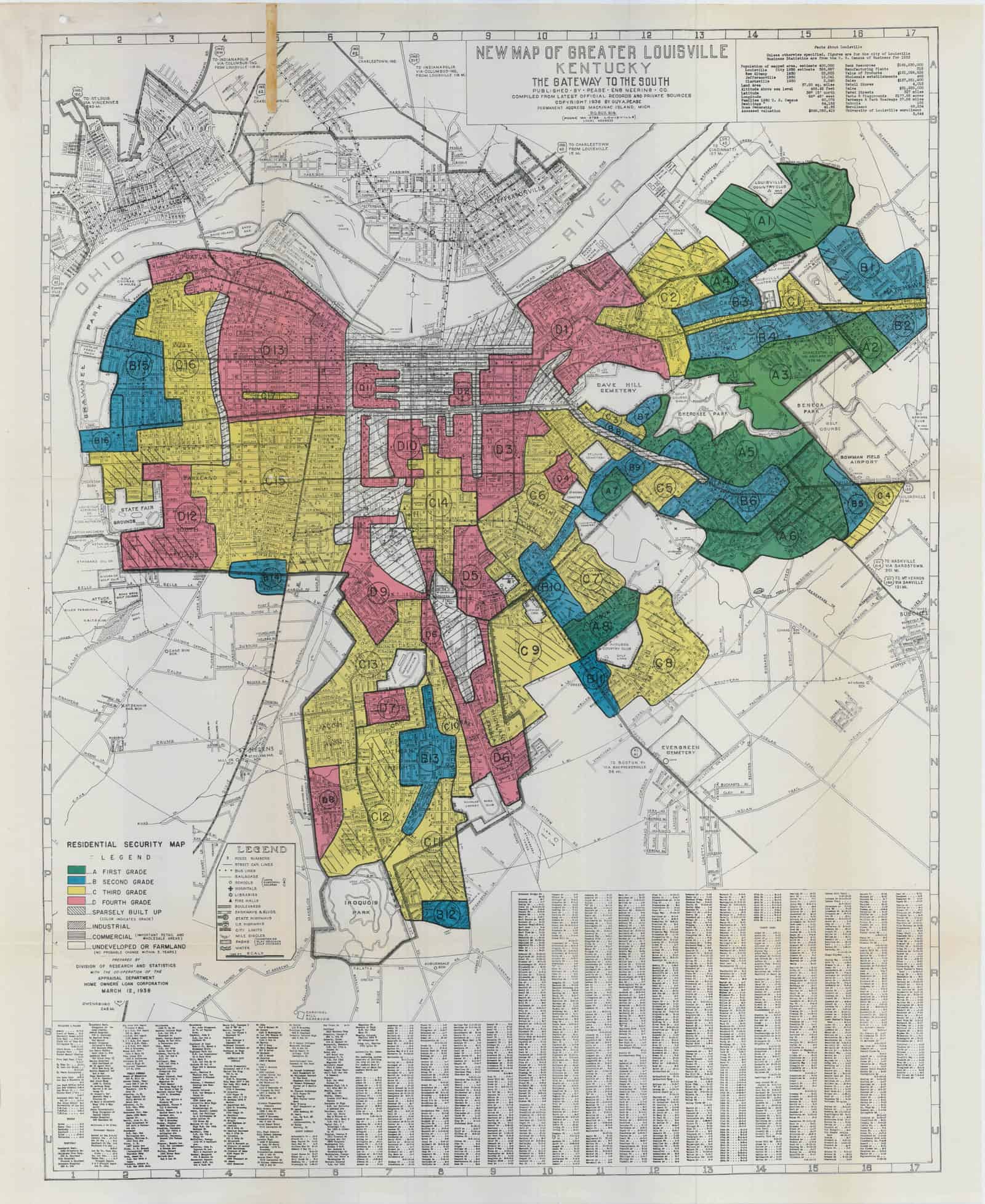

The unfairness between Black and White neighborhoods is stark and vivid. As the great urbanist, Jane Jacobs, once said: “everyone hungers for a first class neighborhood for both pride and dignity … nobody wants a second class neighborhood.” First class neighborhoods are safe, healthy, sustainable, and prosperous. It is a human right, an American right.

John Hans Gilderbloom is director of the Center for Sustainable Urban Neighborhoods and fellow at Neighborhood Housing Services in Washington, D.C., and professor of urban and public affairs at the University of Louisville.

Gregory D. Squires is a professor of sociology and public policy and public administration at George Washington University.

Dr. Robert P. Friedland is the Rudd Chair and professor and chief labortator of neurogeriatrics in the University of Louisville School of Medicine’s Department of Neurology.

Dwan Turner is a west Louisville environmental activist with Master’s Degree in Sustainability at University of Lousiville.

A version of this essay was previously published by the Louisville Courier Journal.

Photo of people marching for justice for Breonna Taylor in Louisville, KY, by Gray Matter on Unsplash