Before the pandemic devastated minority communities, banks and government officials starved them of capital.

Lower-income and minority neighborhoods that were intentionally cut off from lending and investment decades ago today suffer not only from reduced wealth and greater poverty, but from lower life expectancy and higher prevalence of chronic diseases that are risk factors for poor outcomes from COVID-19, a new study shows.

The study adds to the growing body of evidence that many of today’s most economically struggling neighborhoods in urban areas are the same places that experienced intentional, systematic segregation and lending discrimination in the past.

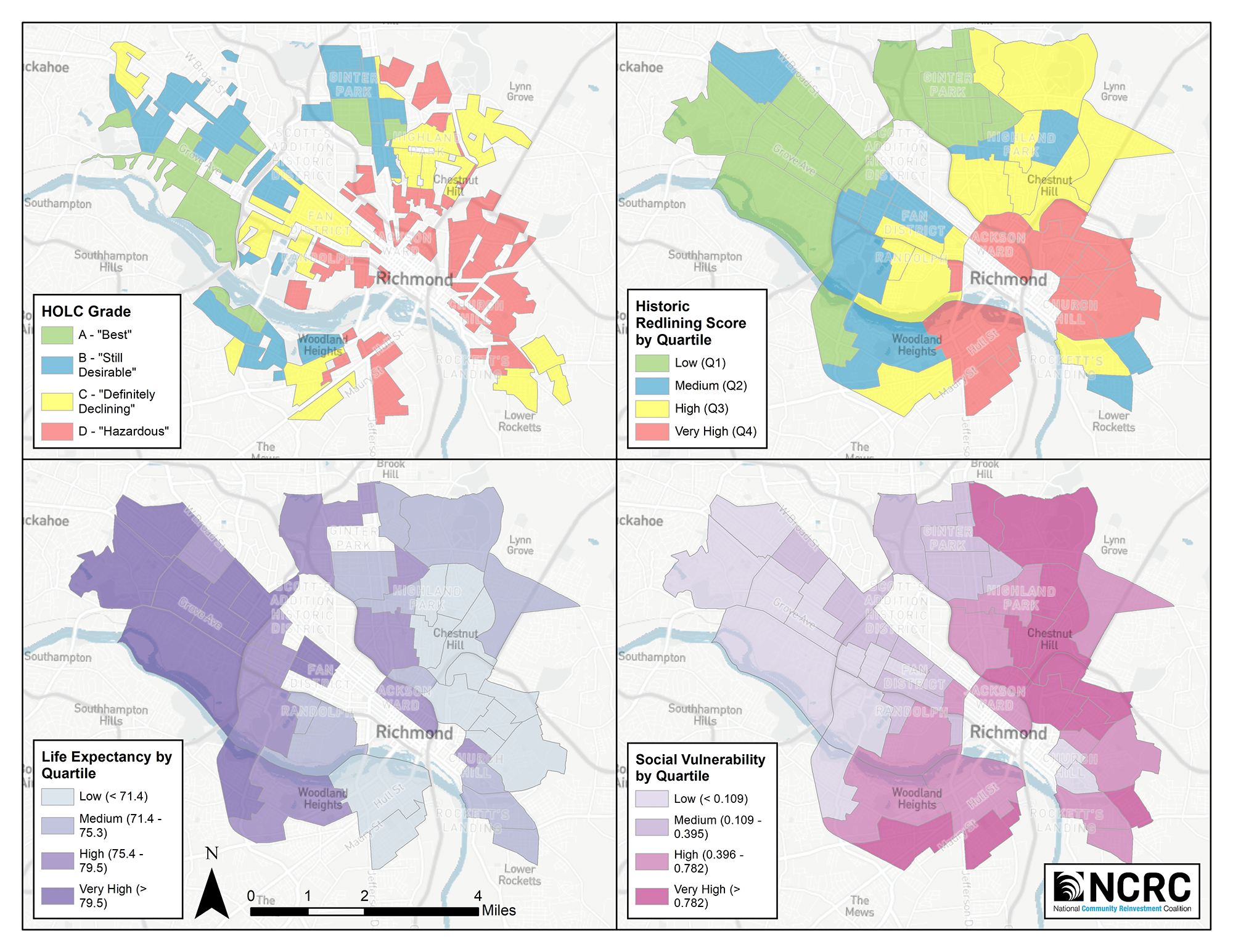

The new study, from the National Community Reinvestment Coalition (NCRC) with researchers from the University of Wisconsin–Milwaukee Joseph J. Zilber School of Public Health and the University of Richmond’s Digital Scholarship Lab, compared 1930’s maps of government-sanctioned lending discrimination zones with current census and public health data.

The maps, created by the Home Owners Loan Corporation (HOLC), marked in red and labeled “hazardous” neighborhoods in cities across the nation that were predominantly occupied by minorities, immigrants and the poor. The color scheme on maps like these gave rise to the term redlining. Similar maps were used by banks, real estate brokers, local and federal government officials to segregate and intentionally starve those neighborhoods of bank loans for home purchases and small businesses. Redlining continued for decades, until Civil Rights-era laws outlawed it beginning in the 1960s.

A 2018 NCRC study found that three out of four neighborhoods marked “hazardous” in the HOLC’s 1930 maps were still struggling economically.

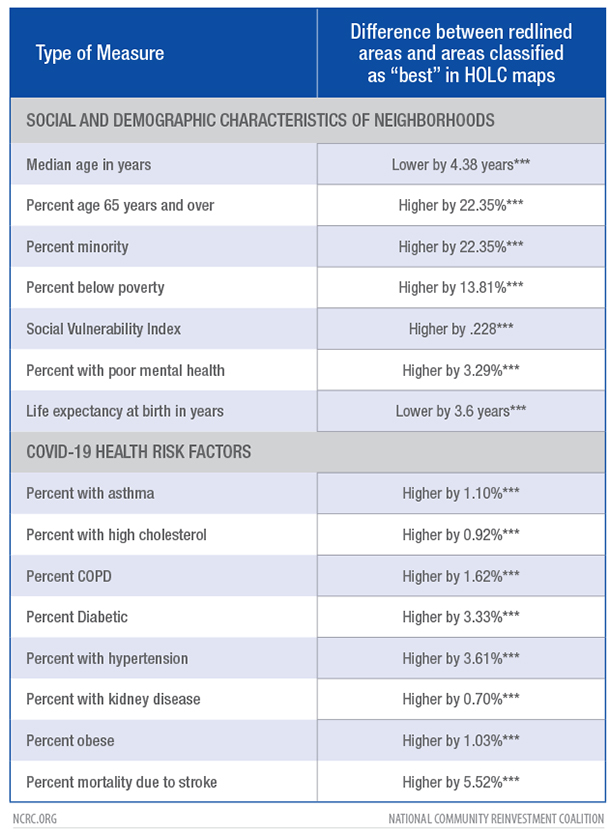

The new study reveals a stark, life-and-death correlation between redlining and health outcomes in those same neighborhoods today: more chronic illnesses like asthma, COPD, diabetes, hypertension, high cholesterol, kidney disease, obesity and stroke. The prevalence of those illnesses increase the risk of poor health outcomes from COVID-19; and life expectancy in redlined neighborhoods is 3.6 years shorter than in neighborhoods that received the HOLC’s highest rating.

“The world is grappling with a global pandemic not seen in 100 years, but in the U.S., it has also exposed economic and racial injustices from the last century that connect directly to the pandemic risks and impacts in communities today,” said Jesse Van Tol, CEO of NCRC. “The higher rates of COVID-19 infections and deaths in communities of color have been well documented, but this study gives us a deeper understanding of why. Historical structural racism created economic and health disparities we see today. That’s an old problem, but the pandemic should be a wake-up call. It’s also an urgent problem for our generation. We’ve got to repair the generational damage caused by redlining and eliminate the extraordinary risks endured by entire communities thanks to intentional, systematic, government-sanctioned disinvestment and discrimination in the past. It’s time to confront the history and work to repair the damage.”

In the new study, researchers generated new maps to show health and life expectancy data in the communities shown in the original HOLC maps.

The data revealed:

- Greater historic redlining is related to current neighborhood characteristics, including increased minority presence, higher prevalence of poverty and greater social vulnerability.

- Statistically significant associations between greater redlining and general indicators of population health, including increased prevalence of poor mental health and lower life expectancy at birth.

- Differences in life expectancy vary greatly among cities: from 14.7 years less in redlined neighborhoods of Rochester, New York, to a 1.3 year greater life expectancy in redlined neighborhoods of Ogden, Utah.

“Structural racism and disinvestment had long-term economic impacts, and now we’ve documented widespread inequities in neighborhood health outcomes,” said Jason Richardson, NCRC’s director of research and evaluation, and one of the report’s co-authors. “That’s a chilling reminder that banking and housing practices and laws aren’t just about money or houses. They are foundational for the economic well-being of entire communities, with long-term consequences. They are literally about life and death, and that’s why they are important for everyone.”

“What struck me when we began this study were the stark differences in life expectancy of neighborhoods of the same city only a mile or so apart,” said Bruce Mitchell, PhD, NCRC’s senior analyst and co-author. “The deeper our analysis went, it became more apparent that the segregation and disinvestment imposed by redlining are associated with concentrated disadvantage and terrible health outcomes for communities of color in American cities.”

“What struck me when we began this study were the stark differences in life expectancy of neighborhoods of the same city only a mile or so apart,” said Bruce Mitchell, PhD, NCRC’s senior analyst and co-author. “The deeper our analysis went, it became more apparent that the segregation and disinvestment imposed by redlining are associated with concentrated disadvantage and terrible health outcomes for communities of color in American cities.”

“It is no surprise that the COVID-19 pandemic has made existing racial health inequities devastatingly clear,” said co-author Helen Meier, PhD, MPH and Assistant Professor of Epidemiology at the University of Wisconsin – Milwaukee. “Disparities in COVID-19 infection and illness severity are a result of widespread social and economic inequities produced by structural racism. Our study found that historic redlining, one form of structural racism, was associated with greater neighborhood prevalence of COVID-19 risk factors, such as socioeconomic disadvantage and chronic health conditions. Health inequities will persist until we address the legacy of racism in the housing market.”

“One of the reasons the HOLC maps are so powerful is that they’re so recognizable. When people look at a map of their city made more than eight decades ago showing the contours of privilege and vulnerability during the Great Depression, they often remark how little has changed,” said Robert K. Nelson, Director of the University of Richmond’s Digital Scholarship Lab. “The calcification of inequalities across the landscape of American cities has many causes; not least of those causes is government policies and programs like the HOLC redlining survey that helped channel public and private resources to native-born, middle-class whites and away from immigrants, African Americans, and other people of color with, as the NCRC report and the mapping site we build with NCRC shows, enormous implications for health disparities today.”

View maps and read the full report:

https://ncrc.org/holc-health

####

The National Community Reinvestment Coalition and its grassroots member organizations create opportunities for people to build wealth. We work with community leaders, policymakers and financial institutions to champion fairness in banking, housing and business. NCRC was formed in 1990 by national, regional and local organizations to increase the flow of private capital into traditionally underserved communities. NCRC has grown into an association of more than 600 community-based organizations in 42 states that promote access to basic banking services, affordable housing, entrepreneurship, job creation and vibrant communities for America’s working families. More: www.ncrc.org

Founded in 2009, the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Joseph J. Zilber School of Public Health seeks to advance population health, health equity, and social and environmental justice among diverse communities in Milwaukee, the state of Wisconsin, and beyond through education, research, community engagement, and advocacy for health-promoting policies and strategies.

The University of Richmond’s Digital Scholarship Lab creates web projects about history and the humanities more generally. They particularly focus on American history and mapping with American Panorama, an award-winning, data-rich, interactive atlas of United States history. More: dsl.richmond.edu and dsl.richmond.edu/panorama

Media contacts:

Alyssa Wiltse

NCRC

awiltse@ncrc.org

540-270-6810

Laura Otto

UWM

llhunt@uwm.edu; media-services-team@uwm.edu

414-303-4868

Sunni Brown

University of Richmond

804-774-9745

sbrown5@richmond.edu