Data is the sunlight that makes possible the fight against discrimination. The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB), however, is considering changing its method of disseminating loan data that would make it less readily available to the public and significantly hamper our collective ability to root out unfair and discriminatory practices.

Before the advent of publicly available data, neighborhood advocates were frustrated in their battles against redlining and discrimination. They knew some banks discriminated against their neighbors, but the banks would call their bluff. The banks said that stories of discrimination did not prove a systematic pattern and practice of discrimination.

Congress passed the Home Mortgage Disclosure Act (HMDA) in 1975 to provide citizens with a powerful data tool to combat discrimination and redlining. The statutory purposes of HMDA include determining whether banks are serving credit needs and identifying and curbing discriminatory lending.

HMDA’s answer to the opacity of discrimination was the public availability of data, which enabled concerned citizens to document the pattern and practice of redlining. Discriminating banks either changed their practices voluntarily after the data exposed their misdeeds or they were sued by government agencies that used data as key evidence to document redlining and discrimination.

An investigative journalist, Bill Dedman, was an early user of HMDA data. In 1988, a series of powerful articles called the “Color of Money

,” appearing in the Atlanta Journal-Constitution, documented striking lending disparities in white and African American middle-income neighborhoods in Atlanta. This series of articles helped convince Congress to improve HMDA data to include not just the census tract location of loans that Dedman had used to document disparities but all the demographics of the loan applicants. Around the same time, the Department of Justice (DOJ) under the administration of George H. Bush used HMDA data to pursue one of its first lending discrimination lawsuits against one of the largest lenders in Atlanta, Decatur Federal Savings and Loans. DOJ used HMDA data to document that from 1985 through 1990, 97 percent of Decatur’s loans were in white census tracts and none of its 43 branches were in predominantly African American tracts.

Following in the tradition of Dedman’s investigative journalism, NCRC has published HMDA-driven research over the years. Some of NCRC’s reports that drew much attention include “Best and Worst Lenders” and “Income is No Shield against Racial Disparities in Lending.” Countless local agencies in cities as diverse as Philadelphia and Santa Fe asked for our help in using HMDA data and seeking to work with lenders and other stakeholders in combating disparities identified in these reports.

Over the years, literally hundreds of NCRC member organizations have likewise asked for NCRC’s help in using HMDA data to hold lending institutions accountable. Without HMDA data, it would not be possible for Community Reinvestment Act (CRA) exams or the bank merger application process to identify where banks are performing well and where they need to improve in serving minority and lower-income borrowers and communities.

Some of the best proof that HMDA and CRA are successful at increasing lending comes from recent Federal Reserve studies. Economists at the Federal Reserve of Philadelphia

documented that when a census tract becomes CRA ineligible (due to metropolitan area boundary changes), home lending decreases between 10 percent to 20 percent. Another study

found a similar impact in small business lending.

One key reason HMDA and CRA cause increased lending is that banks understand that at any time, anybody can use the publicly available data and publish unfavorable findings if banks are not making good faith efforts to lend in all neighborhoods. Hence not only is public availability of data essential, it must be made available in a manner that is easy for anyone to use, regardless of whether you are a researcher, an investigative journalist or a concerned citizen. I have used the data countless times without using complicated statistical software. That’s because the data is available over federal agency web sites as either summary tables or as easily downloadable spreadsheets.

The CFPB and the Federal Financial Institutions Examination Council (FFIEC) both maintain HMDA websites. For years, the Federal Reserve Board maintained the HMDA part of the FFIEC web site. The Federal Reserve’s maintenance of the FFIEC website may have been a bit clunky, but it established a suite of HMDA products, tables and downloads that were accessible to users of all levels of expertise.

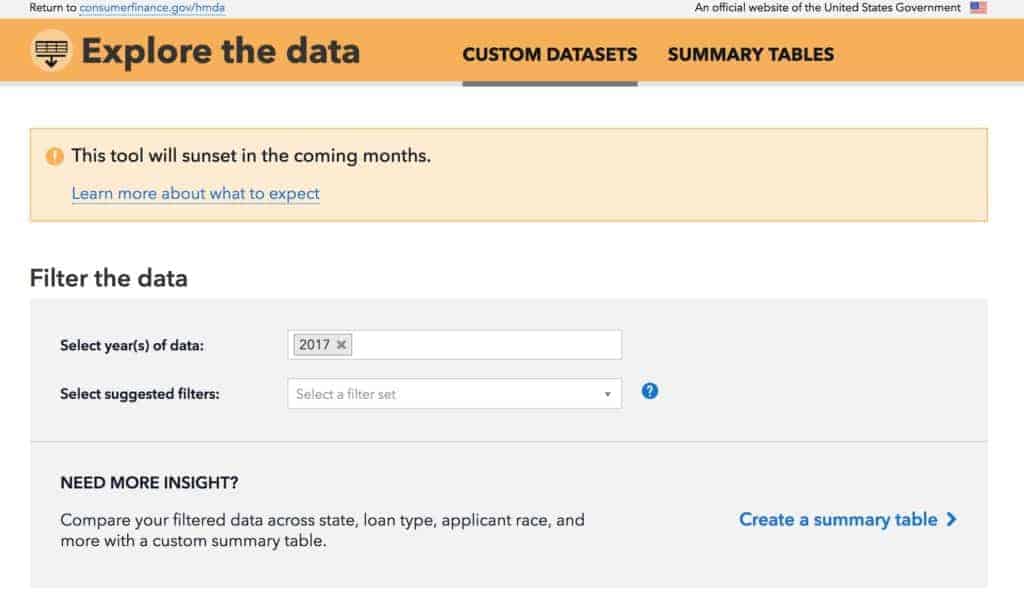

When the Dodd-Frank Consumer Protection and Wall Street Reform Act of 2010 passed, it gave the CFPB authority over HMDA, including its public dissemination over the internet and effective control over the HMDA portion of the FFIEC website. The CFPB also created a tool called HMDA explorer that allows a user to design their own queries and tables or to download the raw data.

All was well until a couple of weeks ago when NCRC noticed that the CFPB posted a message on its HMDA Explorer website – that it will be discontinued. We then asked the CFPB staff questions about HMDA access. They tentatively answered that they will endeavor to maintain the ability to download the data, will reintroduce some sort of query engine (though it may not be as robust as HMDA Explorer) and that many of the tables on the FFIEC website may go away.

This is not terribly reassuring. For NCRC, the easy-to-use public availability of HMDA data is a sine qua non that is non-negotiable. It is one of the most cost-effective means to ensure a fair, equitable and efficient lending marketplace. We have requested that the CFPB preserve all of the FFIEC tables, that the non-academic who uses raw data will still be able to download it, and that the query engine will be rebooted and remain robust.

We must make the case for the critical public purpose of HMDA data, which is to shine a light on unfair lending practices that impede homeownership and wealth-building. We must make the case that data is indispensable for a functioning democracy and a growing economy because data helps make it possible for all citizens working hard and playing by the rules to have a fair chance to buy, sell and maintain homes.

The ability to access data tables and download data may not seem like something to go to battle over, but our neighborhoods need data in order to prevent discrimination or abusive lending. Contact your members of Congress and ask them to demand that the CFPB preserves the public availability of HMDA data. If you know someone at the CFPB, contact them and reiterate the importance of HMDA data. This may seem like a second tier issue, but it is actually of critical importance. Data shines a light that enables us to promote fairness for all.