Image: H Street, Washington D.C. courtesy of washington.org

— Key Takeaways

- This report, based on interviews with 10 Black business owners in historically Black neighborhoods in Washington, D.C., and Baltimore, Maryland, examined the overlooked cultural role of small businesses.

- All of the business owners interviewed for this report asserted that their businesses contributed to maintaining the Black culture of their neighborhoods.

- All made major changes to their operations during the pandemic, and most reported difficulty in accessing pandemic assistance intended for small businesses.

- The idea of businesses being culturally significant or culturally based is conveyed by location, history, and the political-economic contexts in which businesses were established and/or functioned.

Sabiyha Prince, Ph.D., Lead Researcher

Jad Edlebi, Senior GIS Specialist, Research, NCRC

Bruce C. Mitchell, Ph.D., Senior Research Analyst

Jason Richardson, Director, Research & Evaluation

Funding for this study was provided by the Kresge Foundation and American Express.

Executive Summary

In the American public sphere today, there is a lot of talk about culture and its significance in our everyday lives. In U.S. urban centers, the loss of traits that make communities unique and meaningful, particularly to long-term residents, is often due to the impacts of gentrification, redlining, environmental injustices, and the lack of sustained, community-based investment.

Yet, the exact meaning of ‘cultural significance’ is not definitively understood. This lack of a clear definition makes it difficult to support direct investment into culturally significant businesses such as COVID-19 relief that can be critical to business owners and the community members who patronize them.

Given this broader context, our study had two important goals. One was to arrive at a meaning for culturally significant businesses that allow designation to drive programs and investment across different communities. We hope that stakeholders, community leaders, lenders and policymakers can use this definition to craft policies, programs and legislation that support culturally significant businesses. These are the businesses that are critical to defining and promoting communities that have faced obstacles in the face of natural disasters, economic recessions and systemic inequality.

The second goal was to uncover and disseminate information on how these culturally significant businesses fared during the COVID-19 pandemic. Culturally significant establishments are essential to their communities. Their continued presence can offer critical support for well-being by providing access to safe and welcoming spaces for the community. These businesses are also crucial to the availability of strategic, required or highly valued goods and services near residents.

The term culture refers to the shared but diverse, changing and sometimes contested sets of values, beliefs and practices that connect populations with mutual identities and experiences that have formed over time. When we talk about culture, we mean the complex and interwoven behaviors and practices that create the setting for the human interactions that define a community.

This report examines the overlooked cultural role of small businesses. These businesses have a central place in establishing and maintaining the cultural vibrancy of their communities. In this report, we studied the historically Black neighborhoods of the U Street corridor in Washington, D.C., and Pennsylvania Avenue of Old West Baltimore. Interviews with 10 Black business owners were conducted to understand their views on their businesses’ cultural contribution to the neighborhood. Since 2020 was a year of profound political, social and economic change, we had intensive discussions with the owners about how their businesses fared and what forms of assistance had been made available. The COVID-19 pandemic threatens businesses’ continued operation, no matter what the race of the owner. However, it has been especially damaging to Black-owned businesses that may lack the access to capital or grants that would enable them to continue operating.

Specific frameworks for evaluating businesses’ cultural significance also stem from their stories that sit at the center of this report. It was also important to avoid racially-based stereotypes and this objective was bolstered by taking business owners’ viewpoints into account, reviewing African American studies scholarship, and consulting with researchers who focus on Baltimore and D.C. as their life’s work.

This process led us to identify six criteria for determining the cultural significance of businesses. The businesses included in this report meet most or all of these criteria:

- History – The length of time the business has been in the community.

- Location – The value or importance of the place where the business is located. The community can gather there and be comfortable, sharing experiences and information.

- Function – The particular goods and services offered by businesses are important or serve specific needs of the community or they reproduce the culture of the community.

- Relationships – The staff or owners engage in meaningful, often sustained, interactions with residents and patrons.

- Political and economic context – There is a historical persistence of inequality and unfairness for businesses and the communities from which they hail.

- Symbolism – There have been pivotal factors that have coalesced into cogent representations for the business owner and the community they serve or where they are located.

This study takes an expansive view of culture, recognizing that the concept of culture extends beyond just the performing or visual arts. African Americans are uniquely positioned in the United States, possessing a dynamic culture born, in part, out of resistance against enslavement, segregation, racism and inequity.

The burdens business owners have endured due to the COVID-19 pandemic took many forms and fostered experiences of change and loss. Difficulties included decreasing patronage, adhering to changing public health guidance, adjusting to disrupted supply chains and increased costs, finding the time to learn new strategies, as well as the constant threat of being displaced or having to close altogether. These challenges can be added to a heightened concern for their personal well being and the health of their families, staff and communities overall.

— Key FINDINGS

- All of the owners interviewed noted their location in an historic Black neighborhood, and saw their role in the creation and maintenance of that history.

- All but one of the subjects were either natives of their city or were long term residents of the metro area.

- In the District, many business owners discussed gentrification and how the U Street corridor was impacted by a steady erosion of Black culture.

- In Baltimore, only one participant mentioned gentrification. Instead they focused on issues having to do with economic stagnation and rates of vacancy. Some expressed despair over abandonment, poverty and lack of services in their communities. Other Baltimore business owners were hopeful about redevelopment efforts.

- Like all business owners, the subjects were concerned about the impact of COVID-19. Businesses that were able to pivot or adapt to the pandemic reported that customers were eager to support them.

- The subjects all reported difficulty in accessing pandemic assistance intended for small businesses. Some were able to get Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) loans, but the Economic Injury Disaster Loan (EIDL) program was viewed more favorably by the subjects.

- Some subjects in D.C. were able to access assistance from the city, but none of the Baltimore business owners reported that the city offered them any support.

- Numerous business owners shared the strong appreciation they have for their patrons and how the community helped them survive during this pandemic. Patrons took deliberate steps to express this support whether it was continuing to spend with them by ordering takeout food or advertising by word or mouth and through personal social media sites.

- The majority of the participants in this study had longevity in the cities where their businesses were located. Most were natives of Baltimore and D.C. and those who were not born in these cities had resided there for decades.

- Gentrification was a topic that came up in conversations without prompting. Every participant made a comment about this development and the D.C. residents were most emphatic about this issue, stating that their presence was all the more important given the demographic shifts occurring in the Great U Street area. The pace of gentrification hasn’t been as rapid in Baltimore but these entrepreneurs also discussed the perceived inevitability of such changes occurring along Pennsylvania Avenue.

- All but one of the Baltimore entrepreneurs owned the buildings in which their business were located compared to only one in D.C. Ownership offers both a source of equity as well as the ability to resist displacement. This disparity, where owners in Baltimore appeared to be more likely to own their building, may contribute to the reason owners in D.C. repeatedly mention their concern with gentrification.

- The social movements of 2020 were important to many of the people interviewed for this report. Owners interviewed noted that patrons were intentional about supporting Black-owned businesses. In Baltimore, some owners noted that they felt their role in the community led to their businesses being spared damage during the sometimes destructive uprisings that followed the deaths of Freddie Gray, Breona Taylor and George Floyd.

- Business owners reported having to make numerous adjustments in response to the COVID-19 virus. Where possible product sales were shifted online to keep businesses afloat, but this change was not without cost. Shifting to online services brings new tasks and responsibilities that may require additional training.

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic revealed substantial social disparities in its impacts across individuals and groups. African American, Indigenous and Latino American populations disproportionately contracted the disease and faced an increased risk of adverse outcomes. In addition to the higher rates of morbidity and mortality for these groups, inequities also extend from the public health realm to economic considerations, including consequences for businesses run by entrepreneurs of color.[1]

Business owners are a diverse demographic, and data show that the most striking differences along racial-ethnic lines emerge from comparisons between White and African American business owners. Between February and April of 2020, African American business owners decreased by 440,000 or 41% compared to 17% of White business owners.[2] When the race-specific statistics are aggregated by gender, additional disparities emerge. African American women-owned businesses declined by 19.9% between 2017 and 2021, contrasted against the overall rate of a 6.3% loss.[3] This decrease must be considered against a backdrop of substantial earlier growth in Black female entrepreneurship, an increase of 50% between 2014 and 2019.[4]Given this scenario, it appears the COVID pandemic curtailed these previous rates of growth back to disparate 2018 levels.[5]

This pilot study used interviews with Black entrepreneurs working in Baltimore and Washington, D.C., to illustrate the impacts of the COVID-19 virus on these establishments and highlight the roles culturally-significant businesses play in the communities they serve. With a focus on producing a qualitative report that emphasizes interlocutors’ stories, this research generates textured understandings of the challenges Black self-employed women and men face. The report also includes the production of uniquely detailed maps that situate each business geographically and demarcate these historically significant areas within each city.

This report centers on storytelling rather than statistical representations of the pandemic’s disparate impacts in these communities. It begins with a literature review that provides context for the interview data presented in the form of business profiles. The experts in African American history and culture and U.S. Black entrepreneurship cited here illuminate these complex and ever changing conditions by connecting them to long lasting structures of power and the perpetual search for autonomy that defines so many aspects of the African American experience. These and other Black businesses’ cultural significance is explained and understood by tracing this past, assessing contemporary barriers to success, and then placing the businesses engaged within this dynamic context. Special attention is also given to types of businesses profiled in relation to the particular goods and services they provide and other specificities of operations. With this combination of analytical approaches and data-gathering methodologies, this project offers a unique opportunity to present qualitative representations of Black entrepreneurship in two changing U.S. cities.

The concept of culture and its relationship to place anchors the data analyses for this qualitative project. Sociocultural anthropologists have written about and debated over its meaning for decades, and laypersons often conflate the word culture with music and art. Early anthropologists defined culture as an uninterrupted whole that unites communities through shared beliefs and practices.[6] Today, however, it is better understood as a layered and complex force that can be observed in patterned behaviors related to religious practices, family formations, political and economic structures, and artistic and performative expressions, among other institutions and forms of and settings for human interaction.[7] While not unequivocally shared within societies, culture connects groups with overlapping histories and identities. Still, it is also contested, constantly changing, rooted in broader societal contexts, and varied, even within groups perceived externally as homogeneous.[8]

Communities have consistently argued over what values and practices should be central, with intra-group differences continuing to thrive as forces for change, whether forged by generation, socioeconomic status, gender and other social variables. In cases of inadequate access to cultural preservation resources, common vulnerable communities, individuals and groups often face limits on their ability to hold on to what they view as significant.[9] Understandings of cultural significance also rest upon the extent to which communities tacitly or explicitly agree on which elements they can or cannot do without and how these values are expressed. Power relations can undermine culture regardless of a collective desire to retain cherished aspects of community life. Delimiting forces have important implications for the loss of African American businesses with the larger environment of historical Black areas.

These nuances inform the way this pilot study views the connection between culture and place. Ideas about place can reflect multiple community standpoints as well, and when this concept is applied to commerce, the diverse needs and values within communities are further on full display. These complexities are reflected in this report which presents data on a range of businesses, including establishments owned by families and those run by individuals, workplaces that are brick and mortar and those that are solely virtual, as well as businesses owned by Black entrepreneurs of varied ages, genders and backgrounds.

A businesses’ significance related to history reflects its tenure in the community and the presence of a dedicated clientele that supports the entrepreneurial endeavor. Function is a factor that emphasizes how the specific goods and services provided convey significance even in the face of African American diversity. For this element, issues of food, health and wellness, adornment, arts and performance, and identity, among others, are key considerations. Businesses that promote camaraderie and access to information by providing a gathering space for Black people pertain to relationship-formation and are also culturally significant. These interpersonal relations may be local in orientation or speak to Black concerns that are national or international in scope.

While this study’s focus was on multigenerational Black people born in the United States, connections across national origins were also on display, as evidenced by the engagement with businesses with ties to the African diaspora in terms of goods and services. Political, economic context and the power of symbolism are the final two factors related to cultural significance. The institutional and structural barriers African Americans have had to navigate on the road to business ownership come into focus here as well as the meanings that are generated.

The following literature review shows how history plays such a central role in fostering cultural significance in general and the particular geographic areas this project targets. Both geographic areas of concentration are deeply embedded in African Americans’ past struggles and achievements in each city.

Literature Review

African American Businesses and the Struggle for Equity in the U.S.

African American businesses did not just become vulnerable in 2020. In addition to facing greater than average rates of pandemic onset closures, African Americans have confronted persistent barriers along the path to becoming ‘their own boss.’[10] Racist resentment has been a pervasively debilitating factor limiting the achievements of self-employed Black workers in the U.S.[11] During the post-bellum period, businesses owned by African Americans, particularly those that were viewed as successful, threatened a rigid stratification system that placed people of African descent at the bottom of the social hierarchy.

At a time when the majority of employed Black people were hired as domestic servants, agricultural workers and manual laborers, African American business owners were living contradictions of those expectations.[12]The bitterness their presence stoked, whether in the northeast, midwest or the American south, endangered the existence Black business owners as evidenced by, among other examples, the life story of Ida B. Wells.[13] This investigative journalist, and formerly enslaved person began her career in anti-lynching advocacy after Thomas Moss, Calvin McDowell and Henry Stewart were killed by a White mob in 1892. These men were close friends of Wells’ and joint owners of the People’s Grocery Company which competed with nearby White counterparts in Memphis, Tennessee.[14]

Murder and the destruction of Black-owned businesses by racists motivated African Americans to flee communities that were much more racially heterogeneous during the early 1900s.[15] These actions led to the establishment of large, segregated Black communities that were served by thriving Black businesses yet still vulnerable to the aggression of neighboring residents. During the post-Reconstruction era, entire Black towns, many of which were considered economically independent and phenomenally successful, were demolished because of this hatred.[16] One of the most notable of these attacks took place in 1921 in the Greenwood District of Tulsa, Oklahoma, now better known to the general public as “Black Wall Street.”[17]

A lack of proximity and the potential for retaliation from White competitors has meant that African American entrepreneurs of the past have, typically, been “detoured” from operating business in segregated, non-Black neighborhoods.[18] Around the turn of the 20th century, scholars such as W. E. B. DuBois[19] and Henry Minton[20] were researching the specificities of post-slavery Black entrepreneurship. Where historians have generated useful insights into African American entrepreneurship in the U.S., pioneering social scientists and other scholars have struggled to convey the full complexity of the Black American experience.[21]

Frameworks such as ‘middleman theory’ for example, have run into roadblocks by not differentiating between the experiences of multigenerational U.S. born Black people who have not “sojourned from country to country” as immigrants from Asia, Latin America and other parts of the world have.[22] The analytical asymmetry that overlooking chattel enslavement, mob rule and the impacts of institutional racism caused helped promote ideologies of Black victim blaming in writings that posited any gaps in entrepreneurial achievement between African Americans and other non-White and non-Christian immigrants to the U.S. are the fault of Black culture rather than structural barriers.[23] This orientation then generated counter arguments that folded into consideration the barriers African Americans had to overcome to own their own businesses and concluded that neither culture or motivation were discrepancies.[24]

Institutional racism, whether adequately attended to by scholars of African American businesses or not, remained unthwarted in the following decades of U.S. Black life. Discriminatory practices in lending and real estate sales such as the redlining of Black neighborhoods blocked access both to mortgages and business loans over decades, resulting in under capitalized businesses, devaluation of home values, and the systematic denial of wealth building opportunities.[25] Cooperation between insurance companies and banks in particular has shaped the availability of safe and sustainable housing for Black Americans and home ownership acquisition more specifically.[26] Federal housing legislation did not sufficiently mitigate the corrosive actions of banks and insurance companies that harmed Africa American communities across the U.S.[27] Black business ownership has not been immune to the persistent economic vulnerability that these practices have generated in their communities.

Despite, or perhaps because of the hurdles African Americans had to jump over to achieve their entrepreneurial dreams, Black business owners are frequently viewed as trailblazers in their local communities.[28] Being seen as sources for consistency and care, as well as employment, strengthens the relationship between businesses and communities – developments that enhance a sense of cultural significance. Moreover, because entrepreneurship has been viewed as a “pathway to self-reliance,” it has emerged as fundamental to both community identity and the contours of Black urban life during the latter portion of the 20th century.[29]

That said, there has never been a consensus among African Americans about what role Black owned businesses should play within their communities. Some segments have adhered to the ‘Black capitalism’ orientation that President Richard Nixon promulgated during the 1970s. Ideas about subsidizing businesses through tax breaks and other incentives have led to public partnerships such as enterprise and opportunity zones.[30] The “narrative of emancipatory commercialism” positions Black businesses as the solutions for poverty and inequality in African American neighborhoods.[31] Opposing perspectives point to the limitations of privileging Black entrepreneurship and wealth accumulation for individual households as a primary force for undercutting structural racism.[32] These countering views include historical examples of African American business people exploiting their communities.[33] Additional researchers use these types of data to advocate for reparations for African Americans[34] and one article in the Science and Social Medicine journal ties reparations to Black COVID-19 virus impacts specifically.[35]

Debates aside, this legacy of struggle and inequality has left deep economic scars in Black communities and along the landscape of Black entrepreneurial achievement. Racism has denied individual Black households of more than $156 billion dollars due to discriminatory asset devaluation.[36] In D.C. specifically, White Americans have 81 times the wealth of African American households according to a 2016 report.[37] Related to these systemic inequalities, African American owned businesses encounter greater difficulty accessing federal aid which would enable their businesses to survive the most severe economic downturn since the 2007-2009 “Great Recession.”[38] Problems accessing capital and federal relief have contributed to higher failure rates for Black-owned businesses, twice that of White-owned businesses.[39] These conditions have implications for the two cities this pilot study focuses its attention on: Baltimore and Washington, D.C.

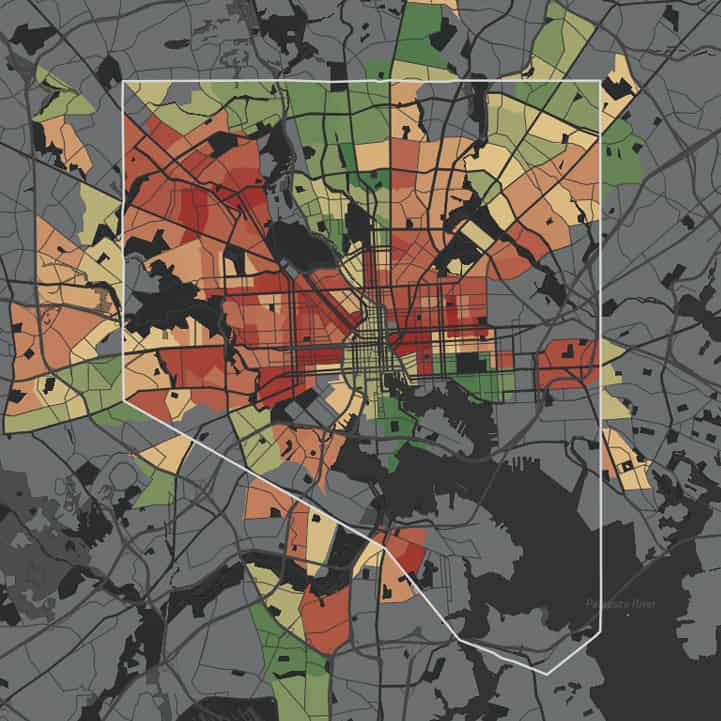

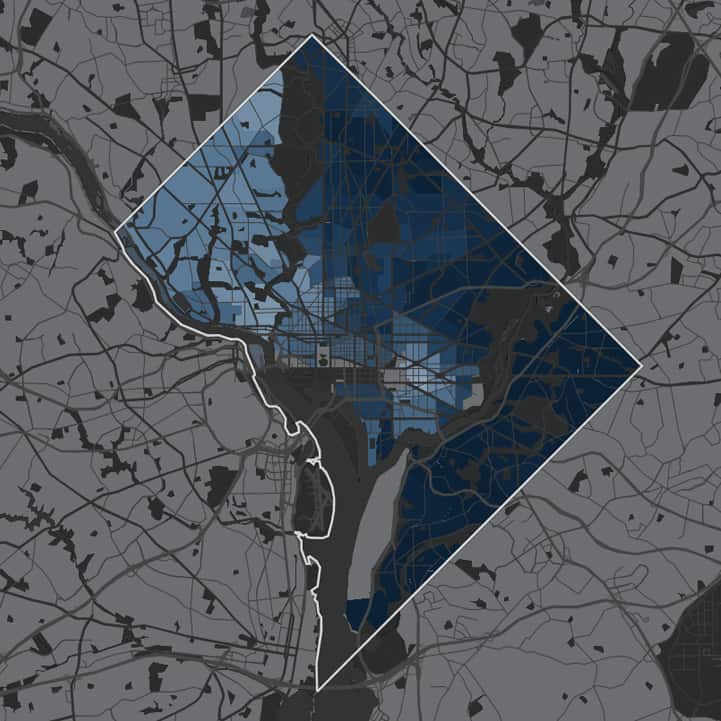

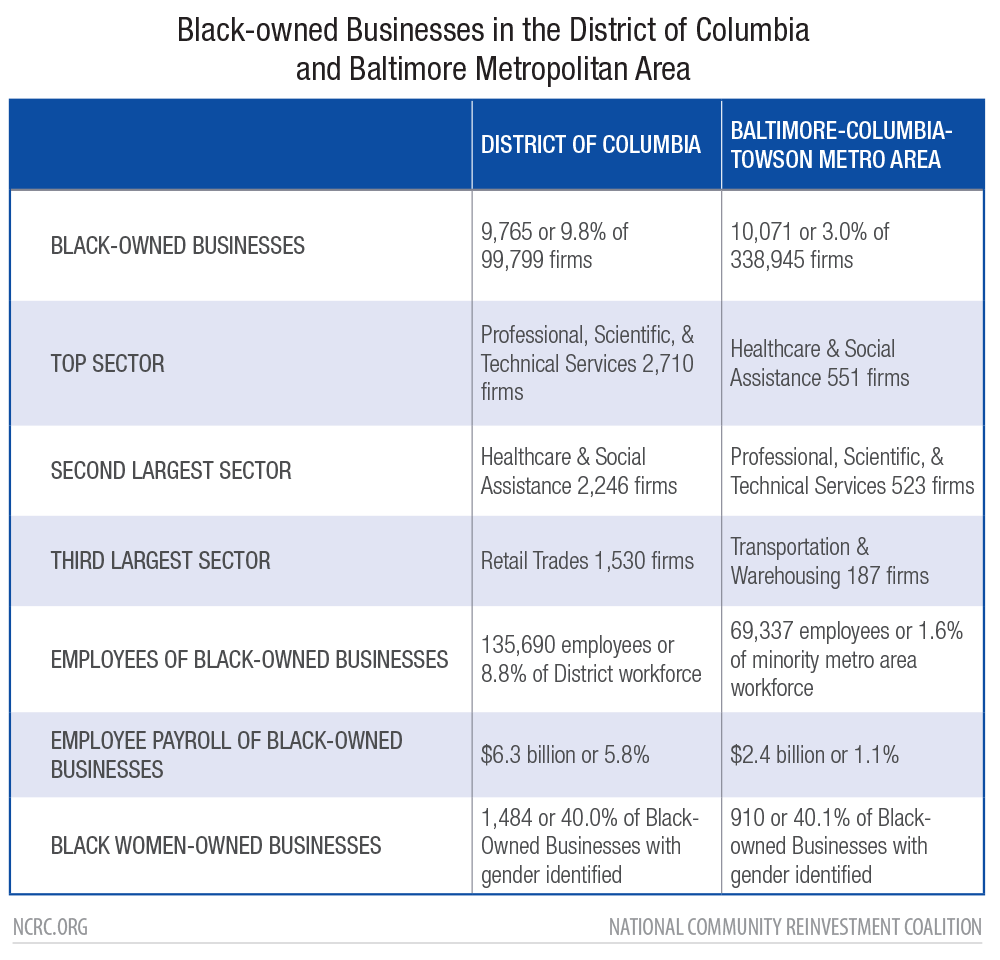

Both cities have large African American populations but business ownership lags far behind the representation of Black residents as a percentage of the population. As reported by the U.S. Census Annual Business Survey in 2017, only 9.8% of the businesses in the District, and 3.0% of those in the Baltimore-Towson-Columbia, Maryland metro area were Black-owned.

These businesses are heavily clustered in service-oriented sectors of the economy: professional, scientific and technical services; healthcare and social services; retail trades in the District, with a much weaker representation of Black-ownership in the greater Baltimore metro area in healthcare and social assistance; professional, scientific and technical services; and transportation and warehousing.

Table 1. Black-owned businesses with employer firm data for the District of Columbia and the greater Baltimore metropolitan area. (Data from the 2018 Annual Business Survey table AB1800CSA01[40])

The current figures on business ownership by race for Baltimore City, which represents a subset of the metro area business community are difficult to calculate because of differences in the way that small businesses are counted by distinct survey methods. In 2012, however, the U.S. Census Survey of Business Owners, including both employer and non-employer firms indicated that 27,673 of the 50,735 firms in Baltimore City – 55%, were minority-owned.[41]

The Cultural Significance of Place in Baltimore and D.C.

Our examination of the COVID-19 pandemic’s impact on African American businesses in Baltimoreand Washington, D.C., focused on two areas within each city. In Baltimore, we focused our inquiry on Black-owned businesses in West Baltimore, portions of which were added to the National Register of Historic Places by the Baltimore Commission for Historical and Architectural Preservation in 2004.[42] The neighborhoods of West Baltimore include Druid Heights, Harlem Park, Madison Park, Mable Hill, Sandtown, Upton, and others, some of which are connected via Pennsylvania Avenue, the historic economic and cultural hub of that vicinity. The Royal Theater, formerly known as the Douglass Theater which opened in 1922, was an important institution associated with the vibrant history of this community. It was demolished in 1971 but the dream of reopening it is one held by many local residents.[43]

“Old West” Baltimore consists of 175 blocks that have been linked to formerly enslaved African Americans since the late 19th century as a home to both the Black working class and those with elite status. This is a community associated with such notable Baltimoreans as performing artists Cab Calloway, Billie Holiday and Chick Webb, as well as the Mitchell family political dynasty, and the first African American supreme court justice, Thurgood Marshall.[44] So many Black-owned businesses dotted the area – African American insurance companies, doctor’s offices and many others including the Associated Colored Orchestras located at 1503 Pennsylvania Avenue during the 1940s.[45]

For the D.C. portion, we turned our attention toward Shaw/Greater U Street and adjacent communities located within the NW quadrant. This historic area, parts of which are euphemistically referred to as Black Broadway, includes U Street, Georgia Avenue, 7th and 9th Streets, and Florida Avenue, among other intersecting streets. The importance of this corridor also stems from an association with vital African American institutions such as Howard University Hospital, which was known as Freedman’s Hospital up until 1975,[46] as well as Howard University and The Howard Theater. The history of segregation connects the latter to a series of “sister theaters” including the Apollo in Harlem, the Earl in Philadelphia, the Regal in Chicago, and the Royal in Baltimore.[47]

The areas within Shaw and around Howard University in Washington, D.C. have connections to Black experiences that also stretch back to the 19th century. A marked presence of African Americans in the area was noted as early as the Civil War and Howard University was founded in 1867.[48] Adding to the area’s reputation, luminaries like civil rights icon Charles Hamilton Houston, composer Duke Ellington, and blood bank pioneer Dr. Charles Drew, as well as basketball legends Elgin Baylor and Dave Bing all worked, trained or lived in this historic area.[49]

Along with the power of history, conditions for residents of contemporary Baltimore and D.C. have both been affected by present-day politics. D.C. residents lack political autonomy due to the absence of voting representatives in Congress. Without complete control over their budgets, gaps exist in the ability of local leaders to shape the destiny of the city.[50] On the other hand, Baltimore has struggled with a series of scandals that have resulted in criminal charges for mayoral leadership.[51]

The pace of urban development and displacement, also shaped by policy, are also distinct in each city. Baltimore significantly lags behind D.C. although there have been discussions about development in Upton and other west Baltimore communities for a number of years.[52] Pennsylvania Avenue or “the Avenue” as it is referred to in the city, has been designated an official arts district by the Maryland State Arts Council with the hopes of using tax incentives and new development to ignite the local economy.[53] Finally, Baltimore is 62.7%[54] African American while D.C. is 47.1% Black.[55]

In both urban locales, cultural significance is conveyed through this legacy of African American history and contemporary struggles.[56] The importance of this broader context cannot be overstated but this report discusses additional, more targeted, ways to think about cultural significance and its relevance for businesses in these communities.

Cultural Significance and African American Owned Businesses in Baltimore and D.C.

There are a variety of factors determining the cultural significance of businesses in general and the business owners engaged with for this project in particular. One key criterion for viewing as business as such is the length of time establishments have operated communities. This pilot-study engaged with entrepreneurs who have had a presence in these locations for decades. Stacie Lee-Banks and her sister Kristie Lee-Jones are co-owners of Lee’s Flower and Gift Shop in Washington, D.C., which has been on U Street since 1945. The Redd family began offering their mortuary services in 1973, Zawadi just celebrated 30 years of doing business on U Street in February 2020 and Avenue Bakery has been on Pennsylvania Avenue since 2007.

These keystone establishments have survived difficult periods in the histories of both cities. Some persisted after the destruction and disinvestment associated with the uprisings of 1968 as well as the more recent disturbances following the killing of Freddie Gray by law enforcement in Sandtown in 2015. Gentrification is another force influencing the staying power of Black owned businesses in both cities; albeit to varying extents.[57] Redevelopment poses a particular challenge for communities in D.C.[58]

Whether the ability to remain is caused by viable and loyal client bases or their ability to adapt to changing conditions in the face of dramatic demographic shifts, continuity adds to the cultural value of these businesses. A sense of authenticity can also be imbued and reinforced under these rapidly changing conditions and these are circumstances that transfer meaning to place.

The specific goods and services offered by businesses are useful for assessing their cultural relevance and impacts on place. The availability of products quintessentially associated with the beliefs and practices of Black community members heightens cultural value however there is variety that negates simplistic or stereotypical depictions. Businesses providing food to the communities they serve was a prime example of this. While African American communities are often associated with southern food traditions, this is not the only discernible pattern related to African American food consumption. Health and wellness concerns, as well as relationships and ideologies that connect U.S. born Black Americans to Africa, the Caribbean and other diasporic locales, also shape African American’s relationships to food in ways that have significant cultural impacts.[59] In this vein, we talked to the proprietors of Capitol Lounge who describe their product as “soul food,” as well as healthy food enthusiast Dominic Nell of City Weeds and BeMoreGreen and filmmaker/business woman Shirikiana Gerima who co-owns Sankofa Video, Books, & Cafe with her husband, filmmaker Haile Gerima. The food choices available at their cafe reflect the geographic diversity of their Black household.

“Afrocentric” gift, clothing and book shops like Sankofa and Zawadi, like businesses that curate African American performing and visual arts, handily meet this expectation as well. Both stores have products that are made by Black film and jewelry-makers, clothing designers, authors, and African-descended artisans and craft persons from around the world. Distributing goods that are directly linked to Black expressive and performative culture holds a lot of salience for cultural significance. These businesses also demonstrate the diversity within populations. Zawadi’s clientele are largely professional African American women. Other businesses, Black-owned distributors of recorded music and urban fashion styles for example, have northworthy levels of cultural gravitas among their key demographic, patrons 35 and younger.

All of these variables have strong and overlapping cultural implications. Music is a force that brings people together and some of the businesses profiled in this report either sold CDs or used music to commune with patrons and build community ties on a regular basis or during yearly celebrations. Avenue Bakery proprietor Jim Hamlin would hold events with live music or DJs in the courtyard of his store on Pennsylvania Avenue in Baltimore. The owners of Sankofa would have musical performances in the back of their establishment periodically although Shirikiana Gerima reported getting complaints from area newcomers about the noise.

There were also connections between commerce and Pan Africanism, those beliefs and practices that connect people of African descent across national origins, that have important cultural implications in D.C. With its unique inventory and network of patrons, Zawadi is linked to this vibrant and dynamic ideological orientation in a city known for African-centered businesses and religious and educational institutions.[60] There were a number of businesses of this type on Georgia Avenue near Howard University where Sankofa is currently located. These were in close proximity to the HBCU, and other African-centered businesses including Blue Nile, a shop specializing in herbs, incense and natural foods, and Pyramid Bookstore that is no longer there.

An additional feature fostering cultural significance among businesses is the role they play when momentous events unfold in the communities they serve. This is exemplified in the example of the massive street protests that took place on U Street in D.C. during the summer of 2019 over a threat to a Black-owned business that was not engaged for this project. After a nearby condominium resident attempted to use his influence to end the broadcasting of D.C.’s own go-go music from a Central Communications/Metro PCS store on the corner of Florida Avenue and 7th Street, the store almost closed. When news of Donald Campbell’s woes spread, thousands of local residents peacefully protested over a number of days. Largely composed of Black residents under the age of 40, this specific but large demographic used their power to save a valued community resource – a store that sells cellular phones and related electronic accessories as well as music. These mobilizations became known as the Don’t Mute D.C. Movement.[61]

In addition to demonstrating diversity within groups, the example above also shows that the availability of familiar, comfortable and welcoming spaces infuses locations with value and meaning. These are the qualities that center barbershops and hair salons in mainstream discussions of African American owned businesses and in American popular culture depictions. In those specific examples, phenotype, in the form of hair texture and the skills required to braid, straighten, cut, intertwine or otherwise style Black hair, has created these homogeneous gathering places where people can “be themselves” away from the gaze of other populations. Services can also be highly specialized. For example, many Black women contend with hair loss for a variety of reasons and A New Image Hair Salon addresses this specific problem.

A strong presence of businesses that cater to a Black customer base can take on visual significance extending from blocks and streets to entire neighborhoods and this can generate a formidable impact on the culture of the place. For communities that have historically faced discrimination, stigma and disinvestment, common for west Baltimore and greater U Street in D.C., the remaining presence of these kinds of establishments sparks nostalgia by harkening back to a time when these corridors were safe and welcoming places.

Businesses owned by celebrities or highly-respected community members also enhance visibility and cultural importance. Kenneth Brown grew up across the street from the Capital Lounge, the Pennsylvania Avenue bar and restaurant he owns. Proximity to vital community institutions is a related characteristic to note. Both of the communities we looked at for this study had hospitals, schools, theaters and hotels that either served or were run by African Americans. These histories convey meaning and these landmarks become synonymous with the identities of communities from within and the perspectives of those who live elsewhere.

The tenor of the relationships that are formed between business owners and the people they serve in neighborhoods is another indicator of cultural significance. This characteristic was conveyed in conversations with a number of project participants who shared earning the respect of patrons through acts of kindness to staff and surrounding community members . Forming ties with houses of worship was another way these relationships were solidified. Samuel Redd of Redd Funeral Services discussed the many charitable activities his business supports in the Sandtown, Baltimore area.

Another way of understanding the link between cultural significance and business is to imagine its disconnect in communities. The replacement of African hair braiding shops with tanning salons and the shuttering of spaces where jazz or go-go music are performed live can signal decline. Such a dearth can result in cultural voids, a potential lack of pivotal services, as well as a loss of identity. This concern mobilized thousands to save go-go from being muted in the city. The displacement of most go-go music performance spaces into neighboring Prince George’s County, Maryland, has born out this fear.[62] Jazz clubs have also closed in the wake of redevelopment and the COVID-19 virus.

Context is an important consideration in analyses of cultural significance and Black businesses. This literature review has shown how, for Black business owners, policies and practices of the past have placed constraints on the availability of the typical resources self-employed Americans would require to achieve success. Discrimination and segregation have shaped the contours of Black entrepreneurship in each series of Baltimore and D.C. neighborhoods. While these processes have fashioned both areas into havens for African American citizens to live relatively autonomously, both areas have been disinvested in historically. The consumer base therein, moreover, has low rates of wealth accumulation.

It is because of these conditions that African American residents were able to engage in economic activity unrestricted by racist practices that prevented them from being hired, receiving reliable service or even touching the items they wanted to purchase. In essence the existence of communities like these allowed the population to participate in commercial activity unmolested by the disregard and maltreatment associated with racism.[63] These are the layered and persistent conditions through which the magnitude of cultural import is forged in these neighborhoods.

Attending to the salience of symbolism is as much of an analytical imperative as considerations of structural inequalities and the historical import. For example, Dominic Nell plans to open his corner store in the spring of 2021. On the road to realizing his dream of offering healthy food options to an ailing community, Nell will be an outlier among Black small scale grocery store owners. An African American store owner may have been a common sight in segregated west Baltimore of old but today, Nell is making strides in an economic niche largely occupied by foreign-born, non Black business owners.

A similar observation can be made of healthcare providers operating in these communities. Optometrist Jessica McClain is charting new territory as an African American optometrist. During segregation these kinds of practitioners were lifelines for vulnerable Black communities. Today, with statistics showing positive maternal and pediatric health outcomes significantly tied to receiving care from Black doctors,[64] these types of businesses are not only culturally and historically consequential, they can also promote health and wellness within entire communities.

Another consequential aspect of context is the exceptional political moment the U.S. is currently experiencing and its bearing on culture. The movement for Black lives has added a sense of urgency to the need to address the legacy of inequality. Phrases like institutional and structural racism, racial equity and microaggressions have become commonplace in the American lexicon. Across the country, leaders from the private sector and governing municipalities are discussing and implementing innovative policies to alleviate the harm of racism and the issue of entrepreneurship has not gone unnoticed in these social justice considerations.

A reinvigorated focus on Black owned businesses has been spearheaded in corporate initiatives and popular culture messaging in the aftermath of Breonna Taylor and George Floyd’s deaths at the hands of law enforcement. The National Basketball Association pledged $300 million to support Black businesses across the U.S.[65] and singer/actor Jennifer Hudson is the face of MasterCard’s $500 million campaign to help businesses run by African American women.[66] Megastar Beyonce began her Black Parade charity in 2020 to drive customers and resources toward Black-owned businesses[67] and entrepreneur Aurora James founded the ‘15% Pledge’ during the same year.[68] This fashion designer’s campaign asks retailers to reserve at least 15% of their shelf space for African American brands and has garnered the participation of Macy’s, Sephora, West Elm and Bloomingdales.[69]

These are a few of the campaigns that have emerged within the last year to support entrepreneurship and encourage social justice in the wake of national responses to police brutality. These examples don’t include the additional many grassroots efforts to promote community-based development and Black owned businesses. The actual impacts of these myriad interventions awaits assessment.

In summary, the idea of businesses being culturally significant or culturally based is conveyed by location, history and the political-economic contexts in which these businesses were established and/or function. The specific goods offered to patrons are additional factors influencing cultural considerations. Particular value is generated when products and services are linked to tastes, needs and practices that are tied to the African American experience. As always, this is a determination that should be problematized in recognition of diversity among the Black urban populations examined for this pilot study.

All of the businesses profiled in this report are culturally significant. In addition to their location and connection to the history of these places, along with their role as purveyors of goods and services that are uniquely tied to the needs, beliefs and practices of the African American populations they serve, these men and women are taking an exceptional approach to earning an income. They are walking a path that has fostered both admiration and resentment, depending upon the gaze that scrutinized and evaluated their actions.

Whether the functioning of these businesses is oriented around benefits that are tangible or symbolic for their communities, this project highlights the impacts of the COVID-19 virus on a sample of African American entrepreneurs in Baltimore, MD and Washington, D.C. It is our hope that this exploration increases the understanding of how valuable these businesses are – particularly at this time in U.S. history. The data we have amassed also strengthen insights into the powerful legacies of history and structural hierarchies on policy and culture.

Interview Data Analysis

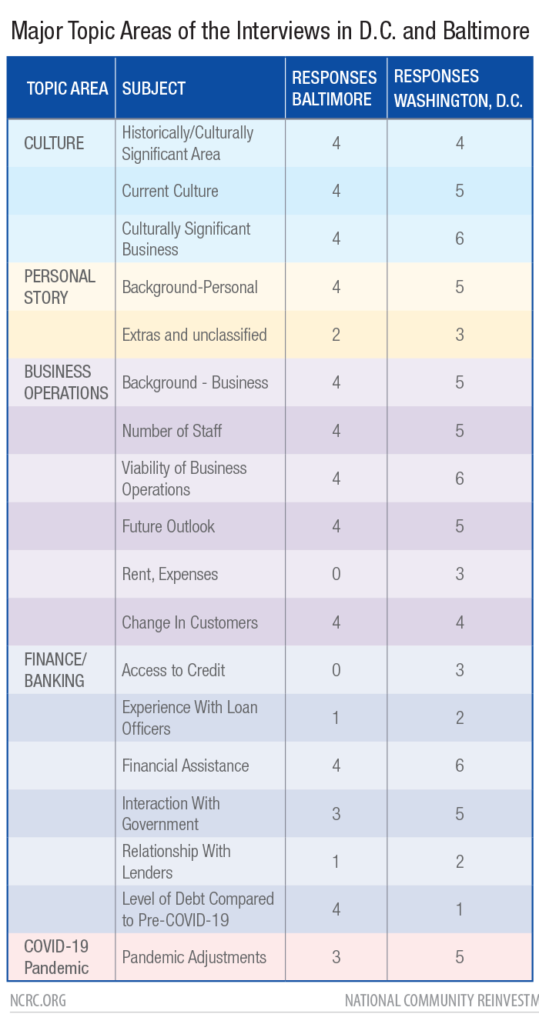

The primary data used in this analysis were the interviews conducted with six business-owners in the greater U Street neighborhood of Washington, D.C.,. and four in west Baltimore, Maryland. The in-depth and semi-structured interviews allowed participants to fully express their views on several questions related to their business operations, the history of the business, the impact of COVID-19 on operations, and their views on whether and how their businesses are culturally significant. The interviews were transcribed, then read and coded using NVivo qualitative analysis software. The scope of the topics identified by the analysis are summarized in Table 1, with five topics emerging from the interviews: Culture; Personal Story; Business Operations; Finance/Banking; and the COVID-19 pandemic.

Table 2. Major topics of the interviews and the subjects discussed. The responses indicate the number of participants in each area that discussed the subject.

The time frame of the interviews, December 2020 through February 2021, spanned several unprecedented national events. The widespread protests of the summer of 2020 related to the murder of George Floyd and a renewal of the Black Lives Matter movement, the 2020 presidential election and subsequent civil disorder culminating in an attack and seizure of the U.S. Capitol building, and the nearly year-long COVID-19 pandemic and nationwide business shut-downs. These events reverberated through the social-political sphere of both the greater Washington, D.C. area and the nation, having profound impacts on the economy. As a consequence, the interviews often reference the local and wider impact of these events on the ability to maintain business operations.

Culture

A key topic of this study was culture and Black small businesses’ role in establishing, maintaining and shaping culture in their neighborhoods. Three themes were established for this topic: the owner’s views on the historical and cultural significance of the neighborhood, its current culture, and the cultural significance of their businesses. Four of the participants from the U Street neighborhood in D.C. referenced historical significance, noting that the area was a commercial hub dominated by Black businesses and services and noting its status as “Black Broadway” with hotels and services where famous Black people stayed. In west Baltimore, two participants cited the historic significance of the area along Pennsylvania Avenue and communities like Upton. One participant specifically recalled the role of the Royal Theater and its status as a venue on the “Chitlin Circuit” for Black performing artists during the era of segregation, and the neighborhood’s tourist potential, and their desire to see the Royal rebuilt as a cultural hub.

Comments on the current culture of the neighborhood centered on gentrification in the U Street neighborhood of D.C., with all six participants either referencing it directly, or its effects. Three of the participants expressed ambivalence about the gentrification they saw occurring along U Street, either “defending it to a certain degree” or citing it as “dynamic.” However, two participants believed that gentrification had diminished Black culture – “(The) culture is gone…feel like it was stolen,” and that “colonizers” and “racism” were factors. Specifically, the demise of Black churches, displacement of Black businesses and restaurants, and the overall cultural and demographic change were mentioned with one participant stating “It used to feel welcoming. I feel sad.” In contrast, one participant from west Baltimore cited gentrification and changes in businesses and affordable housing, but most concerns centered on abandonment, lack of services, crime and also the disturbances and uprising related to the murder of Freddie Gray in 2015. One participant stated “The barrier is the community, and the community needs to start taking pride.” Two participants specifically called for more cooperation, support and networking within the Black community. One participant noted “(We) can’t give up, say lost community and lost generation,” while another was hopeful – “Even if not perfect, perfect for us.” and referenced nearby redevelopment efforts by the City as a sign of improvement.

Participants’ views on the cultural significance of their businesses were focused on its role in the neighborhood as a center of community, the specific services or products which were offered to African Americans, and the affinity of the business for Black patrons – creating a welcoming and comfortable space. In the U Street neighborhood, three of the businesses provided products and services specifically oriented toward African Americans involving hair care, fashion, and art, books, music and videos centered on African studies. Three of the U Street businesses had been open more than 20 years, and the other two more than ten years. Their long tenure allowed the participants to cite numerous instances in which their businesses acted as keystones of the community, hosting musical and other cultural events on a regular basis. As one participant stated regarding Black businesses: “I think they are the culture, so devoid of Black businesses, and those that used to line U Street, so you take those away, you’re taking the culture away.” In west Baltimore, participants also noted that their businesses were vital to the culture of the community, citing mutual support between their operations and the community, and strong ties with their patrons. There was less emphasis on providing products and services tailored to African Americans, and more on how their businesses were keystones of the community in Baltimore.

Personal Story

The interviews covered the personal background and experiences of the participants. Among the participants from the U Street neighborhood, three of the six were natives, and two had lived in the District for more than three decades. At least five of the participants held degrees, (two of the degrees were in Afro-American studies, and one held a degree in optometry) mostly from colleges in the District. Four of these participants expressed strong social or educational motives for their work and a desire to improve cultural understanding within the Black community, with an orientation toward African heritage. Two of the participants were also part of multigenerational occupations or businesses. All four of the participants from west Baltimore were natives of that city. At least one of the participants had grown up in public housing. At least one participant holds a college degree. While only one participant was involved in a multigenerational business, two others were continuing family traditions in their food services businesses by cooking family recipes. The businesses of the west Baltimore participants were just as likely as those in the District to be customer-facing, service oriented operations. One of the participants expressed very strong social motivations, and recounted his involvement in seeing the Black social and cultural history of Pennsylvania Avenue commemorated and revitalized.

Business Operations

Besides noting the length of tenure for their businesses, discussions about business operations were focused on basic facts regarding their employee base, and expenses, and also on the change in customers, the viability of operations and the owners’ views on the future outlook. When questioned about the number of staff, three of the six business-owners in D.C. and three of the four in Baltimore had some staff, or independent contractors working for them. The largest business, in Baltimore, had five full-time and four part-time employees. Most participants in both study areas reported difficulties in their operations due to the COVID-19 pandemic. “Devastating, “Downtown almost completely shutdown,” “business down, and slower” were common responses in both D.C. and Baltimore. There were changes in customers and decreases in demand: “(We) would get busloads of tourists – no more,” and “businesses no longer doing continental breakfasts, normally do pans and half-pans, down to quarter pans now”… “caterers (are) having a hard time.” Some participants reported difficulties in their supply chain, and also increasing costs. The exceptions were businesses which could adapt their marketing and services to online sales. Two of these businesses indicated that they had transitioned to an online presence extensively utilizing social media and were prospering as a result. They credited this partly to the social movement around Black Lives Matter, and a renewed interest in patronizing Black-owned businesses, especially those offering books, jewelry or cultural items. Service-related businesses, which relied on face-to-face interactions with their patrons, seemed to be suffering losses. Many of these businesses reported that they had laid-off staff and reduced hours of operation. In terms of future outlook, the responses in both areas were mixed, with businesses transitioning to online operations citing a “surge in support for Black businesses,” while some owners of more traditional service oriented businesses discussed diversifying, transitioning the business to their kids or closing, with one being “cautiously optimistic” after the pandemic abates.

Finance and Banking

Questions regarding the experiences of Black business owners with banks and gaining access to capital to maintain operations focused on their banking relationships, credit access, and availability of disaster relief. Key themes were their access to credit before and after the pandemic, ability to get assistance through the federal Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) or other Small Business Administration programs like the Economic Injury Disaster Loans (EIDL), interactions with local government, and access to other forms of financial assistance.

Only three of the six participants who owned businesses in the U Street neighborhood of the District discussed their relationships with lending institutions, while five discussed grants. Concerning access to credit, one of the District participants sought access to a business credit card early in the COVID-19 pandemic and before other forms of relief became available, but was denied by their bank. Two of the participants indicated that they received government loans/grants through the PPP, while another three expressed frustration with the confusion over access, changing rules and extensive requirements of the program. Three of the businesses received assistance through the SBA EIDL program, and found that the requirements of that program were clear, with one receiving rapid assistance from their bank (Industrial Bank, which is Black-owned) in submitting their application. Two businesses also received assistance in the form of grants from the District.

The participants from west Baltimore seemed even less likely to have relationships with lending institutions than those from the District. Only two of the four discussed this aspect of their businesses, and indicated that they were not seeking access to credit, though one mentioned they had received a three-month modification to their mortgage. One participant recounted that banks “didn’t make it easy for African American businesses” to get a loan. In terms of assistance from government loans and grants, only one participant received a PPP loan/grant with others indicating that they were ineligible or didn’t apply because of the complexity of the paperwork and lack or help or encouragement. It is unclear the extent to which lack of a banking relationship played in this low level of use. Two of the four businesses received assistance from the EIDL disaster loan program. None of the participants received assistance from the city. One business owner applied for a grant from the Baltimore Development Corporation, but did not receive any funds.

COVID-19 Pandemic

The COVID-19 pandemic and its impact dominated discussions regarding business operations. This profound downturn in demand necessitated reducing hours and laying-off employees, which was discussed in a prior section. Business owners in both study areas recounted the COVID-19 pandemic adjustments to their way of doing business. Two of the six U Street businesses stated that their operations had been totally halted in a lockdown of the District. One Baltimore business had temporarily closed. Five of the six U Street D.C. and three of the four west Baltimore business owners referred to steps that they had taken to maintain operations, while adhering to public health guidelines for social distancing. Service oriented businesses restricted access by closing their lobbies by only allowing curbside or walk-up access, or had limits on the number of patrons allowed in-store. Face coverings were required both for employees and patrons, hand sanitation stations were created, and some businesses such as a funeral home required temperature checks of all visitors. Social distancing measures were also enforced, with the removal of tables and chairs and markings on the floor delineating a six-foot separation between patrons. It was sometimes difficult for the business owners to enforce social distancing, with one owner expressing exasperation with patrons who entered the store without face coverings. One owner of a personal services oriented business stated that they “…would have stayed at home if I could” because of the risk of contracting the virus.

Changes in business operations to utilize social media and establish an online presence were mentioned previously. Some participants discussed how they had further adapted their marketing strategy utilizing Facebook for ordering, email lists of customers. Shifts in delivery of services entailed wider use of Zoom and other social media for events, and implementation of delivery service. The COVID-19 pandemic has resulted in profound changes in the way in which the participants do business. Participants who could rapidly change their operations to an online marketing and delivery model were met with increased demand.

Summary

Analysis of the interviews revealed the profound impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on current operations. The adjustments which the Black business owners made in the marketing and delivery of services often involved an extensive reworking of their operations. All of the participants asserted that their businesses contributed to maintaining the Black culture of their neighborhood. Many provide services that specifically serve the needs of their community by selling cultural items like clothing and jewelry or media and books related to Black or Africana studies. Further, many business-owners sponsored events which enmesh them within the community fabric of the historic Black neighborhoods of greater U Street and west Baltimore. Business owners in the two study areas seemed to face different challenges. The District has been impacted by an extensive erosion of culture through gentrification, while Baltimore faces issues of residential abandonment and economic stagnation. All of the businesses were small, with the largest employing a total of nine full and part-time workers. Many of these businesses benefited from the Small Business Administration Economic Injury Disaster Loan program, but fewer were able to participate in the PPP, with only one of the west Baltimore businesses gaining PPP assistance. Additionally, participants in the District reported greater assistance from their local government, and seemed to have stronger banking relationships. This analysis is based on coding and aggregation of the responses taken directly from interviews. More detailed and specific interpretation is provided in the narratives following this section.

Discussion

Businesses occupy a hallowed space in American society. They are both a symbol of economic hope and an engine of social mobility. In every community there are businesses that help define the success and scope of that community. These are culturally significant businesses. In this report we examined Black businesses in Washington, D.C., and Baltimore, MD. These are two cities with vibrant histories of Black culture but divergent fortunes. Interviews with business owners in both cities reveal ways in which culturally significant businesses support and are supported by the communities that they serve. All of the people interviewed discussed similar experiences with federal pandemic relief programs. They spoke about how they struggled to meet the demands of a virus that nobody expected, they voiced frustration with local bureaucracy. The study also revealed how local differences in the larger community they are a part of impact the health of these businesses. Among the similarities, subjects interviewed for this report in both cities noted the value of longevity, of providing spaces for Black people to congregate, and of providing services that every community needs to flourish. But the differences are instructive as well. Black business owners that rent their space are highly conscious of their precarious position when rents and property values rise. The high costs of operating in D.C. versus the lower revenue available in Baltimore are a symptom of larger patterns of investment and abandonment. The goals of this report were to develop a methodology for identifying culturally significant businesses and determine how the stresses of the pandemic were impacting them. We have clearly enumerated the characteristics of a culturally significant business; longevity, location, function, relationships, political and economic context, and symbolism. Furthermore, we find that the stresses of the pandemic are similar in some respects, but can vary widely based on the locally specific policies and economic resiliency of the surrounding city. Our findings support the need for further research into a wider variety of local communities and in cities across the country to better understand how stakeholders, business organizations, trade groups, and municipal, state and national leaders can target aid to businesses that are critical to the continued survival of these communities.

Appendices

Appendix A.

Glossary of acronyms

CDC – Centers for Disease Control

D.C.RA – D.C. Regulatory Authority

D.C.SBDC – D.C. Small Business Development Center

DM – direct message

DMV – District, Maryland and Virginia (The D.C. metropolitan area)

EIDL – Emergency Injury Direct Loan

HBCU – Historically Black Colleges/Universities

PPP– Paycheck Protection Program

SBA – Small Business Administration

Appendix B.

Methods

This innovative project brought an interdisciplinary team of scholars together to generate qualitative data on African American businesses operating during this pandemic. The primary data source for this report is a series of 10 in-depth interviews lasting between 40 and 80 minutes with African American business owners who work in Baltimore, MD and Washington, D.C. . These conversations took place between December 2020 and February 2021 toward the goal of recording detailed accounts of what it is like to operate a business during these historically difficult and changing times.

The idea of businesses being culturally based or culturally significant was a central analytical frame for this research. To explicate this and the other issues the information presented in this report the works of an interdisciplinary cadre of scholars with expertise in African American history and culture, as well as the subjects of entrepreneurship, class stratification, and urban planning and development were consulted. These sources appear in the bibliography at the end of this document.

To better understand what is occurring on the ground, the project also centers the perspectives of interlocutors in their discussions of what constitutes cultural significance in these communities. In addition to recording community-based knowledge and studying secondary sources on the varied issues related to our inquiries, team member, and cultural anthropologist, Sabiyha Prince, also contributed her pedagogical and research experience to the development of this study’s analytical frameworks. This activist, artist, author, ethnographer, former-university professor and native-Washingtonian also relied on her network of social contacts established over many years to locate participants in both D.C. and Baltimore.

The team used the Slack social media platform to share information and stay in contact with each other. There were also weekly noon meetings on Wednesdays in a schedule that was rarely diverted from. When the data began to come in, a shared Google drive was set up to upload audio files, transcripts, photographs and any other pertinent information.

The first two interviews conducted for this project were completed in person until the risks of these actions were recognized. All interviews were recorded, transcribed, and then organized based on the themes embedded in each question. The team engaged the services of a qualitative research consultant who produced more than 250 pages of transcripts and excel documents with participants’ answers organized thematically coded along the lines of access to bank loans, staffing issues, impacts on profit margins, future outlook for businesses, relationships with local government, shifting operations during a pandemic, and other topics.

Participants were also asked about the role their business plays in the communities in which they are situated (see list of questions in appendix). These discussions generated oral history data and information indicative of both the experiences and opinions of these business owners. The data contained in the transcripts also reflected how these communities have changed over the years and what the cultural aspects of these neighborhoods may be. The team developed the questions working collaboratively and the detailed answers are presented in this report at length under the heading business profiles.

The interviews all occurred almost one year after the emergence of the COVID-19 coronavirus, and approximately ten months after preventative lock-down rules were first enacted. This was a period of extraordinary social and political upheaval across the country, and particularly in Washington, D.C.. More than 30 Black business owners were approached about participating in this project by phone call or email and the qualitative researcher had conversations with some. Given the pressures these businesses have had to confront during this span of time, it was not surprising that the majority of the entrepreneurs contacted choose not to participate in this study. Among the responses received, some indicated they wanted to participate but were never available each time they were contacted. Some did not respond at all and another said they were interested but hung up the phone each time they were called.

The business owners interviewed represented a wide cross-section of retail and service-related businesses while two provide key resources such as food and housing. The majority of businesses are customer-facing although three offer the bulk of their services virtually. The following is a list of the businesses engaged for this project:

Washington, D.C.

- Optometrist

- Hair salon

- Florist/gift shop programming

- Bookstore/cafe

- Gifts/housewares

- Virtual administrative assistant

Baltimore

- Bakery

- Bar/restaurant

- Urban farm/educational

- Funeral home

All participants were required to sign release forms to allow their voice and likeness to be used in webinar or website presentations without liability. Some details about their experiences have been excluded to protect their privacy. Some participants expressed skepticism about signing the paper and needed additional reassurance. There were also periodic questions about the reasons for the project and what uses the data would be put to.

Finally, the team included a glossary of terms with this report to explicate acronyms and define or elaborate on concepts and terms that may be specific to the history and culture(s) of the locations from which we gathered data.

Appendix C.

Questions

Introductory questions:

- What is your name?

- What is the name of your business?

- What is the address of this business?

- What is your email address?

- Are you the sole proprietor of this business?

- When did you start this business?

Open-ended questions:

- Are you from Washington (or Baltimore) and if not talk a little about what drew you to this city and where your family originates from?

- Tell me a little about your business, when did you open and what drew you to this kind of business and location?

- Before the pandemic how did you feel about your business and its viability? What were your biggest challenges?

- How has this changed since the start of the pandemic Please talk about how your business and staff have been affected

- What changes have you seen in your customers since the pandemic began? Are there fewer customers, or have those you do have changed in what they expect from your business in any way (touchless service, delivery of items, lower prices etc.)

- Have you needed to seek out credit (in any form, credit cards, loans etc) since the start of the pandemic? How has that changed from prior to the pandemic?

- Have you heard of the Paycheck Protection Program – PPP? What do you think about it?

- Have you applied for a PPP loan, SBA loan or Economic Injury Disaster Loan (EIDL)?

- What lender did you approach about this or other loans and can you describe your interaction with those lenders?

- What is your outlook for your business at this time? Have you considered closing?

- What has your interaction with local government been like since the pandemic and how does this differ from the pre-pandemic period?

- If someone asked you about the culture of this neighborhood, how would you describe it?

- How important do you think your business is to the culture of this community?

Appendix D.

This pilot study examined the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on culturally significant businesses located in west Baltimore, Maryland and the greater U Street area of Washington, D.C.. Transcripts from interviews with self-employed African Americans constitute the primary source of information for this report and the majority of these conversations took place remotely. As poignant and illuminating as these data are, a number of pertinent issues about Black entrepreneurship were not explored in this preliminary study. A list of topics for further research that have implications for the study of self employment more broadly is presented below:

Additional Areas of Inquiry

- Non-profit organizations – Nonprofits have operational duties and challenges that overlap with those of profit-driven entities.Approaches to strategic planning and staffing are among the range of issues more can be gleaned about through in depth studies into these diverse types of organizations. Researchers may also uncover data on the types of relationships that are formed across these sectors.

- Community histories – Stories about a community’s past and the oral histories of residents are more than backdrops to larger studies.These types of data bring greater accuracy and authenticity to the work and constitute enhancements that can also increase the scope and readability of final reports.

- Consumer-base wealth – Examining the rates of wealth accumulation for the clients and patrons of business owners can reveal vital information about possibilities for growth as well as key areas of vulnerability for business owners.This focus also helps researchers underscore the role of discrimination and other forms of inequality in differentiating communities along the lines of race, class, and ethnicity.

- Ethnographic data – First-hand observations made during direct interactions over extended periods of time are invaluable for generating data that are extensive and descriptive.This approach also presents researchers with opportunities to see the differences between what interlocutors say and what they do. Staff management, customer service, and any number of topics related to business operations can be better understood through participant-observation and other methodologies associated with qualitative research.

- Informal Economy – The examination of connections between businesses that are taxed and regulated and those associated with the informal economy can provide useful contextual data, including information on economic status of the larger community they are operating in and details about ways in which these sectors overlap.

- Urban planning – The actions of organizations, funders, ideologies, and individuals that are responsible for the ways cities will look and function in the future are very impactful for business.Studies into how these practices and policies are formed and implemented will bring the upcoming availability of resources and opportunities to light and foster much needed discussions of pending development and the impacts of this for the self-employed segments of the workforce.

[1] https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/community/health-equity/racial-ethnic-disparities/disparities-deaths.html

[2] Fairlie, R.W., (2020) The impact of covid-19 on small business owners: Evidence if early-stage losses from the April 2020 current population survey. NBER https://www.nber.org/system/files/working_papers/w27309/w27309.pdf

[3] https://cdn.advocacy.sba.gov/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/31083212/Black-Business-Owners-Hit-Hard-By-Pandemic.pdf

[4] https://s1.q4cdn.com/692158879/files/doc_library/file/2019-state-of-women-owned-businesses-report.pdf

[5] Personal communication with Josh Devine, March 30th, 2021

[6] Tylor, Edward, B., (1920) [1871]. Primitive Culture: Research into the Development of Mythology, Philosophy, Religion, Art, and Custom. London: John Murray

[7] Miller, Barbara, Cultural Anthropology (8th Edition), Pearson, 2016

[8] Prince, Sabiyha, Constructing Belonging: Class, Race, and Harlem’s Professional Workers, New York: Routledge, 2004

[9] Kendi Ibram X., Stamped from the Beginning, New York: Nation Books, 2016

[10] Wills, Shomari, Black Fortunes, Harper Collins: New York, 2018

[11] Meier, August and Elliott Rudwick, editors, The Making of Black America, Vol. 2, The Black Community in the Modern Era, Atheneum: New York, 1969

[12] Mullings, Leith, Uneven Development: Class, Race and Gender in the United States Before 1900 in Women’s Work: Development and the Division of Labor by Gender, Eleanor Leacock and Helen Safa, Editors, South Hadley, MA: Bergin and Garvey, 1988

[13] Giddings, Paula, Ida: A Sword Among Lions, Harper Collins: New York, 2006

[14] Bay, Mia, To Tell the Truth Freely: The Life of Ida B. Wells, Hill and Wang: New York, 2009

[15] Loewen, James, Sundown Towns: A Hidden Dimension of American Racism, The New Press: New York, 2005

[16] Slocum, Karla, Black Towns, Black Futures: The Enduring Allure of a Black Place in the American West, Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2019

[17] Johnson, Hannibal, B., Black Wall Street, Eaken Press, Fort Worth, Tx, 1998, Tim Madigan, The Burning: Massacre, Destruction, and the Tulsa Race Riot of 1921, St. Martin’s Press, New york, 2001

[18] Gerena, Charles, Urban Entrepreneurs: The Origins of Black Business Districts in Durham, Richmond, and Washington, D.C., Region Focus, Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond. https://www.richmondfed.org/-/media/richmondfedorg/publications/research/econ_focus/2004/winter/pdf/economic_history.pdf

[19] DuBois, William Edward B. The Negro in Business, Atlanta: Atlanta University, 1898

[20] Minton, Henry, The Early History of Negros in Business in Philadelphia, Read before the American Historial Society, March 1913

[21] Walker, Juliete, E. K., The History of Black Business in America: Capitalism, Race, Entrepreneurship, Volume 1, to 1865, Chapel Hill, NC: The University of North Carolina Press, 2009

[22] Bonacich, Edna, “Toward a Theory of Middleman Minorities,” American Sociological Review, 38 October, 1972: 583-594

[23] Butler, John Sibley and Cedrick Herring, “Ethnicity and Entrepreneurship in America: Toward an Explanation of Racial and Ethnic Group Variations in Self Employment,” Sociological Perspectives, Vol. 34(1), 1991: pp. 79-94

[24] Kollinger, Phillipp, “Not for Lack of Trying: American Entrepreneurship in Black and White,” in Small Business Economics, Vol. 27, Issue 1, pp: 59-79, 2006