Marceline White

Executive Director, Maryland Consumer Rights Coalition

Marceline serves as the Executive Director of the Maryland Consumer Rights Coalition where she leads the coalition of 8,500 supporters in promoting economic justice and financial inclusion throughout Maryland. Marceline currently co-chairs the Consumer Protection Committee of Attorney General Frosh’s COVID-19 Task Force. Under Marceline’s leadership, in 2020, MCRC passed the first legislation in the country to close the 90-10 loophole for for-profit colleges and protect students from disorderly closures. Marceline’s advocacy in 2020 also led to the first increase in protections from garnishment for workers in 30 years and an expansion of free and reduced care for medical patients in Maryland.

Marceline has written and advocated on affordable auto insurance, debtors’ prisons, deficiency judgements, foreclosure policy, predatory payday lending, and auto fraud among other issues.

In 2017, Marceline won the National Association of Consumer Advocates’ “Advocate of the Year” award for her advocacy efforts at the state level. In 2017, Marceline also received an Excellence in Advocacy award from the tri-state Common Cents Conference as well as the Lorraine Sheehan Award for Excellence in Advocacy from the Community Development Network (with the CASH Campaign of Maryland ) for their work ending predatory payday loans in Maryland. In 2014, Marceline won an award for best advocacy film from the National Community Reinvestment Coalition for her consumer education film “Stealing Trust”.

In 2016, Marceline served on the steering committee of the Federal Reserve Faster Payments System work group and on the board of directors of the Baltimore Rock Opera Society (BROS). Currently she serves as president of the board of directors of the Consumer Federation of America and as a member of the board of the National Community Reinvestment Coalition. Marceline is also a published essayist, poet, and writer. She holds a Masters of Public and International Affairs from the University of Pittsburgh and a bachelor’s in journalism from the University of Missouri-Columbia.

This is one in a series of essays accompanying NCRC’s 2020 analysis that showed more chronic disease and greater risks from COVID-19 in formerly redlined communities. The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views or policy positions of NCRC.

Hard times in the city

In a hard town by the sea

Ain’t nowhere to run to

There ain’t nothin here for free

— Nina Simone “Baltimore”

Baltimore has been lauded in story, song, movies and television. From the beautiful homes in Roland Park depicted by Anne Tyler, to the formstone rowhomes in many John Waters films, to the Park Heights neighborhood described by Ta-Nehisi Coates, to, of course, the locations throughout East and West Baltimore immortalized in The Wire.

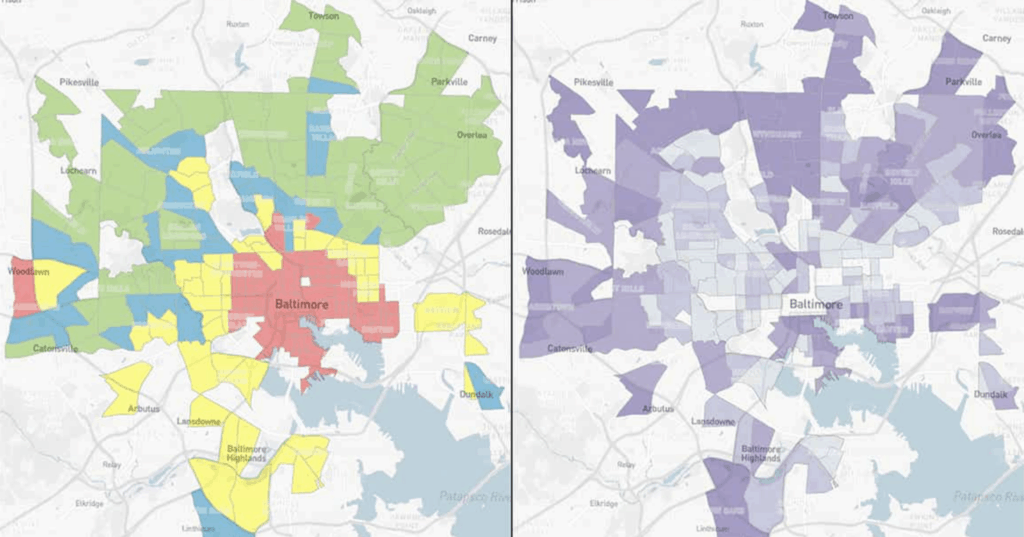

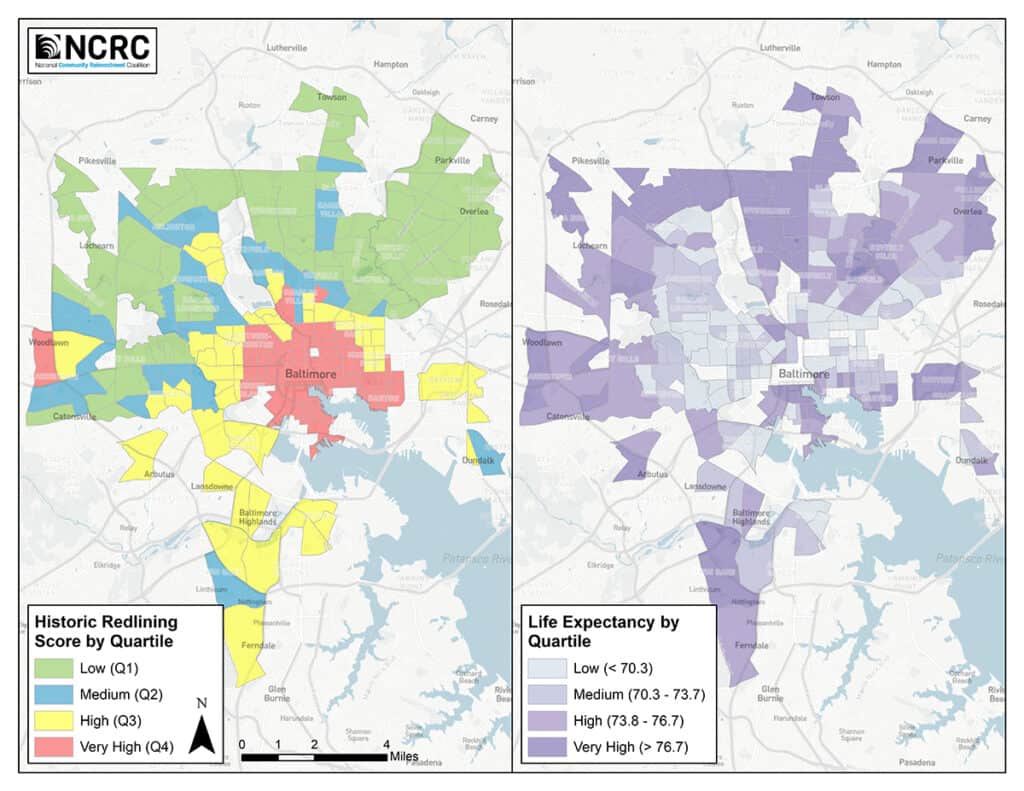

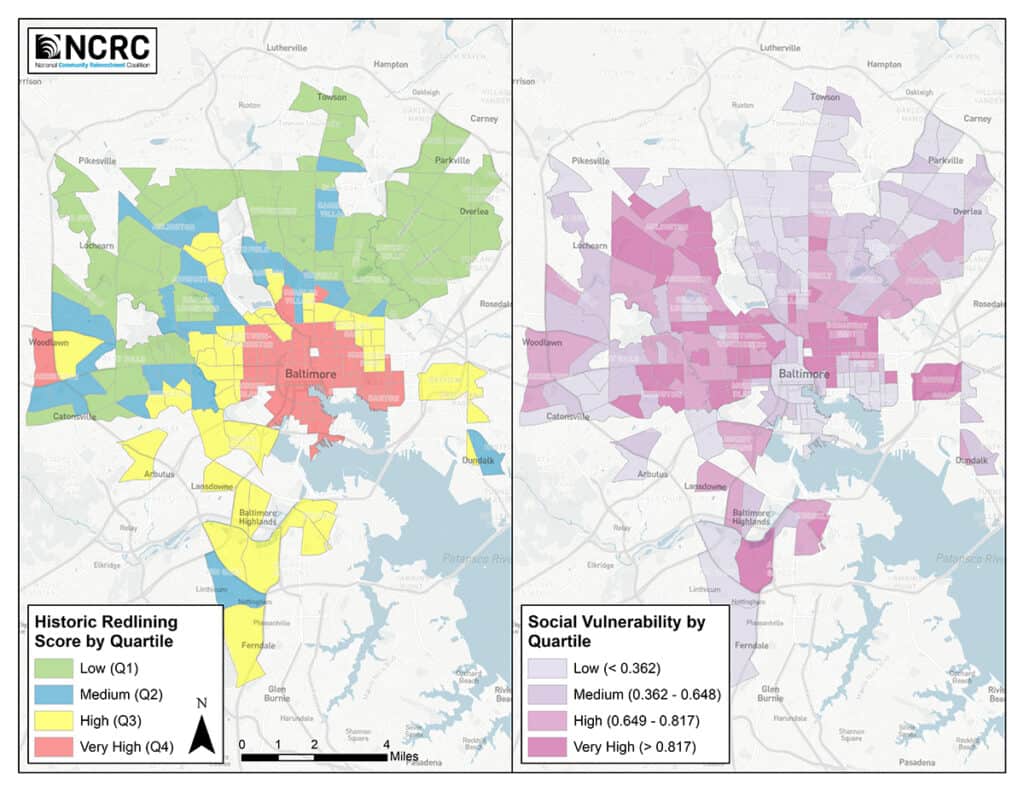

These images illustrate what Baltimore activists describe as “the two Baltimores.” Dr. Lawrence Brown coined the term “the Black Butterfly” to describe the contrast between the “White L,” an area around the Inner Harbor and stretching straight North to the wealthy neighborhoods of Homeland and Guilford, with the low-income, majority Black neighborhoods that make up large swaths of East and West Baltimore.

Prior to Dr. Brown popularizing the idea of the “Black Butterfly,” I had always described the two Baltimores as part of one body, with the mainly White, wealthy neighborhoods comprising the spine and the predominantly Black neighborhoods as the vital organs, the heart and breath of the city.

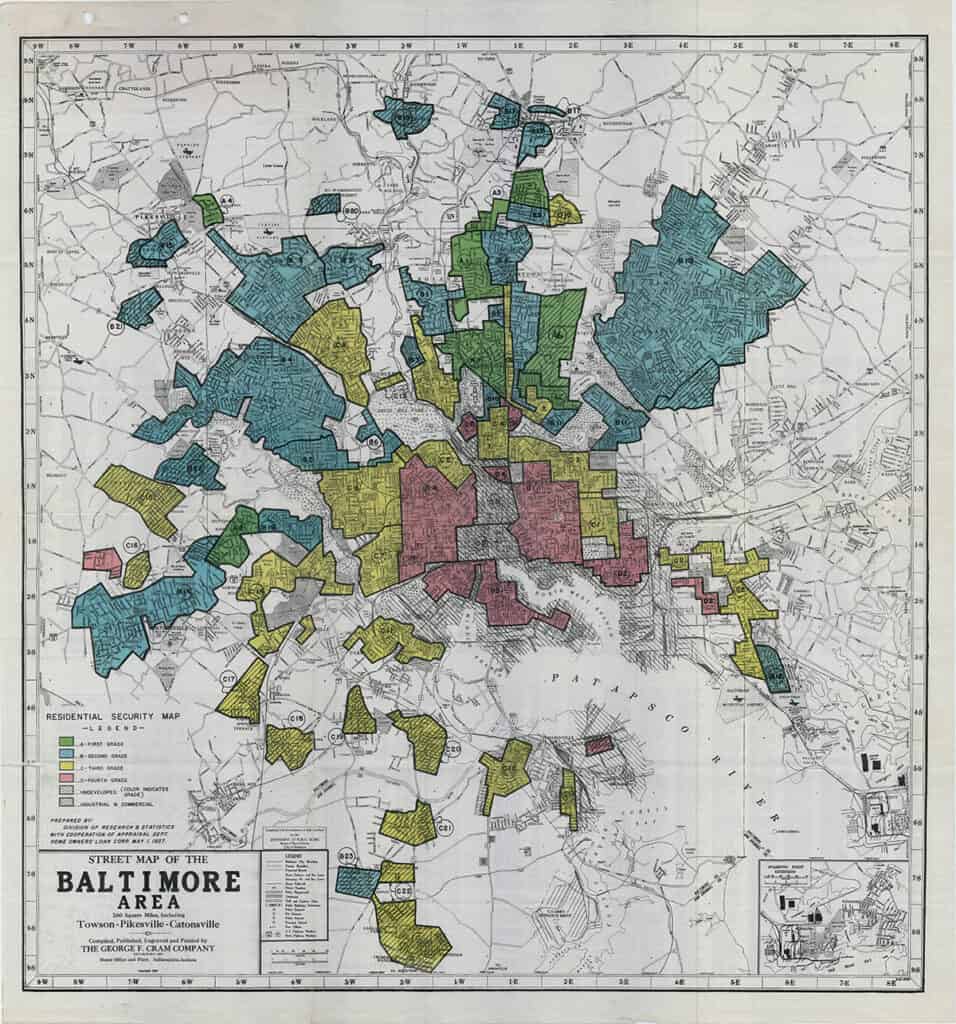

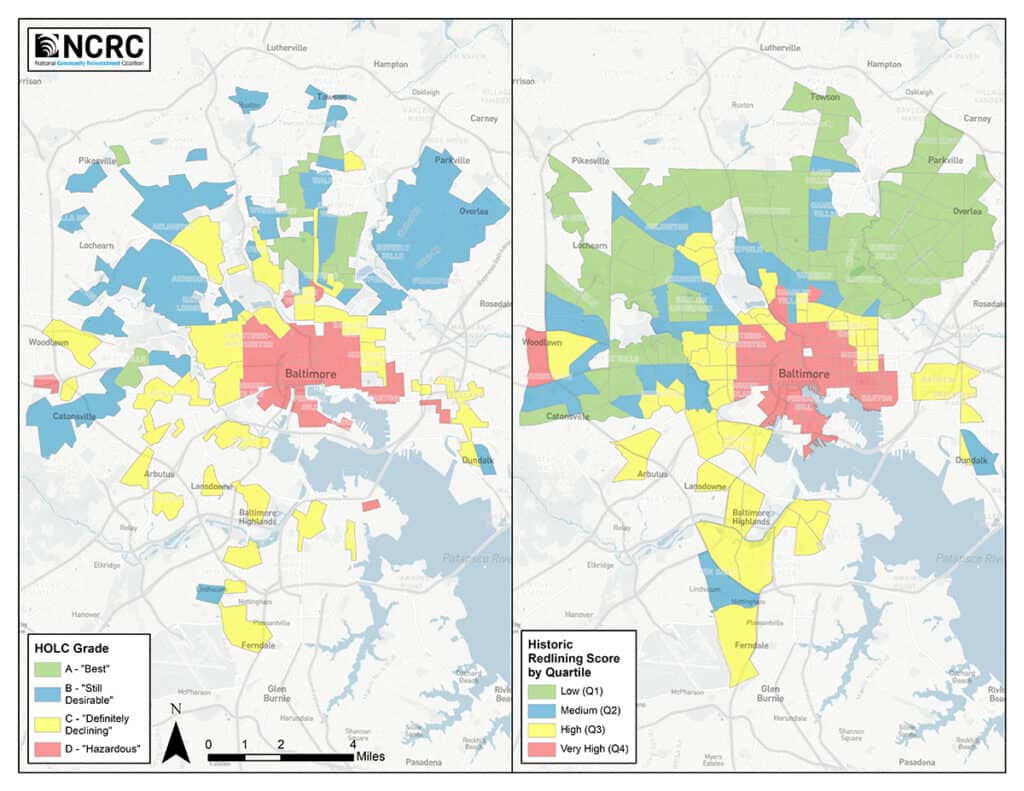

In NCRC’s latest report, the devastating impact of structural decisions on the health and wealth of majority Black communities in Baltimore is evident. What may be less evident is how we got here. It is no accident that Baltimore has bolstered its ‘’White spine” and wounded it’s Black vital organs. Baltimore looks the way it does because of a long history of structural racism. In 1910, the first ordinance on racial zoning was passed; in the 1930s, the Housing Authority of Baltimore City ran two separate and unequal housing programs, one for White families and another for Black families; and following the Great Depression, the Home Owners Loan Corporation (HOLC) marked up maps assessing risks of investing in certain neighborhoods, with majority-Black communities considered the riskiest financial investment and marked in red. This began the practice of redlining.

Consequently, in the 1930s, Black households comprised 20% of the population but were confined to 2% of Baltimore City, concentrated in neighborhoods in East and West Baltimore. By 2000, this pattern remained largely intact; Black households comprised 64% of the population, and 60% of the neighborhoods in the city were at least 60% Black.

This structural segregation leads to a vicious cycle of disinvestment and disparity between White and Black communities in Baltimore. Economists talk about vicious or virtuous cycles which is another way of saying that one action affects another. In Baltimore, this means these formerly redlined, majority-Black communities, experienced economic distress in a number of ways because of segregation. First, homes in majority Black communities sell for less than similar homes in majority White communities. Even when the homes are similar in size and style, the sales price may vary dramatically. According to a Brookings study, there was a $48,000 price difference for similar homes in majority-White versus majority-Black neighborhoods.

If you are not born into wealth, many families rely on their homes to build wealth for retirement or tap the equity to pay for other needs. Consequently, with lower home values, homeowners in majority-Black communities will have less wealth to draw upon, further widening the racial wealth gap. Deprived of equal access to credit to develop, repair or renovate buildings, majority-Black neighborhoods will experience problems with blight; which may lead to calls by policymakers to tear down wide swaths of buildings in these communities. And, while some homes and buildings may be unsalvageable after decades of neglect, it is important to remember that the neglect was due to policy decisions by local and state leaders and financial institutions, not by community members.

As buildings fall into disrepair, the built environment of the neighborhood suffers. Baltimore was the first city to ban lead paint but the toxic paint and dust linger. That’sanother legacy of redlining and another wounding of the hyper-segregated Black communities where lead paint violations are concentrated in dilapidated buildings, rentals that haven’t been brought up to code and in the particulate matter that hovers in the air whenever the city knocks down a row of townhomes. Lead paint at the high levels found in old homes throughout East and West Baltimore is linked to learning disabilities, developmental delays, ADHD, high blood pressure and death.

Poor housing conditions are also a contributing factor to the high rates of childhood and adult asthma in Baltimore. In 2010, rates for hospitalization due to asthma were 2.2 times higher in the city than the rest of Maryland. Mold, mice and cockroaches contribute to high rates of asthma and code violations for these issues are concentrated in rental properties in East and West Baltimore, which have the highest asthma hospitalization rates. The wealthiest zip codes in Roland Park and Mount Washington have the lowest.

Activists and community leaders often lament that it’s the same map: the maps that colored Baltimore’s predominantly Black communities red in the 1930s are the same maps, the same neighborhoods, that are rent-burdened, mortgage burdened, lose homes to tax sales, are pursued at higher rates for debt collection and experience higher auto insurance rates. These majority-Black neighborhoods have been deprived and depleted of resources for decades with neighborhoods starved for grocery stores, banks, tree canopy and more. Instead of grocery stores, communities in East and West Baltimore have corner stores selling junk food at high prices with few vegetable, fruit or other healthy options available. Rather than access to banking services, low-income, majority-Black neighborhoods have high-cost check-cashers, pawn shops and other alternative financial options. It costs more to be poor.

Consequently, these communities experience higher rates of asthma, diabetes and heart disease. Many of these neighborhoods are adjacent to world-class medical institutions, yet do not reap the benefits of that access. Studies show that households with chronic health conditions have higher medical debt, with or without insurance. At the same time, households who live in poverty often lack funds to buy medicine, seek preventive care or other services to improve health outcomes. Stress about money can worsen health conditions such as diabetes and heart disease. So, there is a vicious cycle connecting health inequity and financial insecurity. One that Baltimore hospitals are worsening by suing their low-income patients and garnishing their bank accounts or wages to collect medical debt.

The COVID-19 global health pandemic further exacerbates these existing wealth and racial inequalities. COVID-19 illuminates the connection between health equity, financial security and community investment. Black and Latinx workers have been hardest hit by job losses as industries shed jobs and small businesses closed shop. Black business owners in Baltimore City have been hit hard by the pandemic and with less access to capital, many are concerned about having to close permanently. Again, the pernicious effects of bias may contribute to the fact that fewer than one-third of the PPP loans for $150,000 and abovewent to businesses in majority-Black neighborhoods. Black-owned businesses have fewer relationships with banks and less access to credit.

At the same time, Black and Latinx workers are concentrated in “essential jobs,” meaning that they will go to work in low-waged jobs throughout the pandemic. Their situation is complicated by the fact that many of these residents live in multi-generational households in small homes where it is nearly impossible to quarantine, and they may have chronic health issues that were only sporadically treated as household finances would allow, thereby increasing complications for treatment and recovery. In turn, this increases the likelihood of more difficult emergency health care needs in the future. And concerns about health care costs may delay treatment or increase stress, which, in turn, contributes to poor health outcomes.

The health and economic outcomes in the Black Butterfly, in the heart and breath of Baltimore, are the legacy of discriminatory policies implemented by city leaders at the behest of White communities throughout the 20th century.

Recommendations:

- Baltimore City should require banks to report mortgage and small business investments in majority-Black neighborhoods. Based on report findings, Baltimore City government should consider moving its funds to the bank that performs best.

- Baltimore-area hospitals should cease suing low-income patients, particularly those in majority-Black neighborhoods, for medical debt. Instead, hospitals should be required to offer an income-based repayment plan for former patients before a debt goes to collections.

- Community-based organizations should come together to press banks for greater investment in Baltimore.

These structural policies were not implemented overnight, and they are unlikely to be uprooted and replaced overnight. Baltimore nonprofits, activists, community-based organizations and community leaders cannot afford “business as usual” right now. We cannot afford to work separately and siloed to overcome these systemic issues. Instead, we must work together, one voice in different harmonies, each working to our strengths to call out and root out these policies.

Now, in a time of a global pandemic and recession if not depression, we should not seek a return to normal. Normal was still unjust for many residents in Baltimore, and across the country. Instead, we need to seize this moment to call for transformative solutions based in equity, inclusion and economic rights. This global pandemic has made clear that there is money to make these changes; it is simply a matter of political will.

My hope is that we use this moment to create a new vision for Baltimore across these lines that have separated parts of the city, and that the images that have dominated the media of Baltimore are supplanted by new ones of our rising.

Thank you for connecting the dots. Does Baltimore require lead testing in the certificate of occupancy? Does the county require lead testing as part of the section 8 inspection?