This white paper also benefited from the vision and many contributions by Gerron Levi, former Senior Director of Government Affairs at NCRC. Contributions were also provided by Charlotte Saltzman, a paralegal at Relman Colfax PLLC.

Executive Summary

The Community Reinvestment Act (CRA) was enacted in 1977. It was a response to the nation’s long and painful history of lending discrimination against people of color and the resulting disinvestment and decay in communities of color. Congress’ purpose was to counter decades of official and unofficial redlining and other forms of discrimination by government agencies and the nation’s banks. The law’s author, Senator William Proxmire, and many other supporters over the years have confirmed that this was the impetus for the law.

To counter the effects of discrimination, Congress identified banks’ affirmative duty to meet the credit needs of their entire communities and required federal regulatory agencies to evaluate and rate banks periodically on how well each is meeting that obligation. Limiting the ability to achieve CRA’s central aim, however, regulators have generally interpreted the “entire community” to focus on income. Through regulations and in practice, their chief concern has been how well banks are meeting the needs of low- and moderate-income (LMI) people and neighborhoods. Little direct emphasis has been placed on the needs of people and neighborhoods of color.

It is time for regulators to incorporate an explicit focus on race[1] in core CRA regulations and examination procedures. This should and can be done in a manner that complements, and does not in any way supplant, the longstanding focus on LMI. There are many ways regulators can make CRA more race-conscious that comport with CRA’s language and purpose and with the Equal Protection Clause of the United States Constitution. This paper proposes several and explains why they are constitutional.

The first set of proposals is informational. We call for increasing the collection, calculation and reporting of data about lending to people and neighborhoods of color. This can be done through metrics specific to an individual bank’s performance in its assessment areas (a geographic area defined by the bank as its community) and benchmarks reflecting the demographics of, and the whole market’s collective lending in, the assessment areas. We have designed these measurements to parallel ones proposed last year by the Federal Reserve Board based on LMI.

The benchmarks will help regulators interpret each bank’s performance and enhance their understanding of the local circumstances in which banks operate, called the performance context. To further enhance that understanding, we also propose creating full-time research positions dedicated to studying the racial components of banks’ varying performance contexts, modeled on work done by the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco.

These proposals should not be at all controversial from a constitutional perspective because they do not, to any degree at all, allocate government benefits or impose sanctions based on race. They are comparable to a host of race-based information already collected and published by the federal government, the most basic being the census.

The second set of proposals are about how to incorporate a bank’s record of meeting the needs of people and neighborhoods of color in CRA evaluations and ratings. An Equal Protection question arises here because under most circumstances the government may not act on the basis of race. But it may do so in circumstances that satisfy the “strict scrutiny” test applied by courts. Courts might not construe explicitly race-conscious CRA evaluations as triggering strict scrutiny because good CRA ratings are not a limited government benefit — potentially every bank can earn one — but we assume for present purposes that these proposals would be subject to that test.

Strict scrutiny has two basic components. First, the government must have and provide substantial evidence of a compelling interest to justify its consideration of race. Remedying the effects of past and present discrimination is established in the courts as a compelling interest, and there is extensive evidence that discrimination continues to impair access to credit, and other banking services, for people and neighborhoods of color.

Second, the government must act in a manner that is narrowly tailored to achieving its compelling interest. That means several things of particular importance with respect to CRA. Genuine consideration must first be given to race-neutral alternatives and found inadequate. Racial quotas are anathema, but aspirational and flexible targets are proper, particularly when based on local circumstances, and when consideration is given to banks that attempt in good faith to meet race-based goals but ultimately do not. The burden on third parties — primarily non-Hispanic Whites in this context — may not be too great. And race should only be considered with respect to racial groups, bank products and geographical areas where evidence indicates that access is currently curtailed due to past or present discrimination. Each element of our proposal for incorporating race in CRA evaluations satisfies these requirements.

We make proposals for the retail lending, retail services, community development financing and community development services subtests of CRA evaluations. For retail lending, again paralleling the Federal Reserve Board’s pending LMI proposal, banks should have to reach certain statistical thresholds, or make a good faith effort to do so, to obtain a presumption of a satisfactory rating. Performance ranges could be set for the several other possible ratings, too. In the alternative, examiners could be given discretion to treat excellent performance compared to aspirational goals as a subjective “plus factor” when assigning a rating. The “plus factor” approach should be used for the other subtests. Metrics would be involved in some respects, but examiners would use their judgment with the help of guidelines to promote consistency to interpret and decide how much weight to give the numbers.

Evaluations should also consider whether banks are arbitrarily excluding neighborhoods of color from their assessment areas,which is not currently prohibited but should be. If so, this should be factored into ratings. When a bank has multiple assessment areas and only some are selected for a full-scope review in an evaluation (to the extent the distinction between full- and limited-scope reviews is retained), racial demographics should be added to the list of factors considered in deciding which assessment areas to select. Finally, if a bank chooses to be evaluated under a strategic plan approved by its regulator, it should have to conduct outreach to organizations serving neighborhoods of color when developing its plan.

To determine which parts of the country warrant these race-conscious elements in CRA evaluations, the regulatory agencies should conduct and periodically refresh a study to determine where, for what products, and as to what groups discrimination continues to distort the market. This will assure that race is only considered where it needs to be, consistent with the Equal Protection Clause.

Adoption of these proposals will give regulators a deeper understanding of whether banks are meeting the needs of their entire communities by broadening the crucial but too narrow primary focus on LMI. It will motivate banks to expand their focus in the same way. It will bring nearer the day when everyone has fair access to the critical products and services provided by banks. That is the very reason for CRA.

I. Background of the Community Reinvestment Act and Summary of Proposals to More Explicitly Consider Lending to People and Neighborhoods of Color

A. The History, Design and Successes of the Community Reinvestment Act

CRA”, enacted in 1977, places an affirmative obligation on the nation’s banks to meet the credit needs of the entire communities in which they are chartered, including the LMI households and neighborhoods in those communities.[2] Every two to five years, each of the nation’s three bank regulators[3] examine and release a public performance evaluation and CRA rating for each bank it regulates. Evaluations assess how well a bank is meeting its CRA obligations.[4]

Banks are evaluated on how well they provide mortgages, small business and small farm loans, community development debt and equity financing, and financial services to the LMI borrowers and communities in their “assessment areas.” These are geographic areas defined by each bank that, by and large, include neighborhoods around a bank’s branches. In rating banks, examiners also consider their compliance with the nation’s fair lending and consumer protection laws. In addition to the reputational benefits or consequences of a bank’s CRA rating, regulators consider the rating when a bank seeks to expand and open new branches, and merge with or acquire another financial institution.[5] Ratings range from substantial noncompliance to outstanding,[6] and are applied at both component and institutional levels.

Together with other antidiscrimination and disclosure laws enacted during the 1960s and 1970s, CRA was designed to end and remedy years of lending discrimination by the US government and the nation’s private financial institutions which resulted in racial segregation, disinvestment and decline in lower-income neighborhoods and communities of color.[7] Senator William Proxmire, who authored CRA, expressed the law’s intent: to “eliminate the practice of redlining by lending institutions.”[8] Redlining denies credit to would-be borrowers in certain neighborhoods because of the neighborhoods’ racial or ethnic composition, without regard for the creditworthiness of individual credit applicants. The term comes from the red used on maps to denote neighborhoods viewed as being high-risk, including neighborhoods of color.[9]

While de jure and de facto housing and credit discrimination were widespread by governmental and private actors[10], one notable example that has been extensively documented is the explicitly discriminatory work of a federal agency, the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation (HOLC), created in 1933. The agency developed “Residential Security” maps of major American cities that documented how loan officers, appraisers, and real estate professionals evaluated mortgage lending risk during the era immediately before the surge of suburbanization in the 1950s. Neighborhoods considered high risk, or “hazardous,” were often redlined by lending institutions, denying them access to capital investment which could improve residents’ housing and economic opportunities. Neighborhoods with people of color were systematically deemed higher risk.[11]

CRA and its implementing regulations were enacted and designed to remedy the damage done by these longstanding practices and to ensure that the nation’s banks provide mortgage, small business, and other credit, investment, and financial services to affected borrowers and communities. In many regards, CRA has succeeded in remedying some of the “market failures” associated with underserved communities. In addition to racial discrimination, the law’s drafters recognized that underserved markets would continue to be beset by negative and informational externalities.[12] For example, if lenders fear that other lenders will not lend to areas that are perceived as risky (whether they are or not), they will refrain from lending; the fear is self-fulfilling.[13] The resulting inability to borrow money to buy and improve homes consigns neighborhoods to continuing disinvestment. The lack of home sales increases the perceived risk of neighborhoods because appraisers rely on sales for information on the value of homes when determining appropriate loan amounts. Informational externalities and asymmetries can result in delays, caution about perceived risk and banks charging higher interest rates. Lender expectations of this sort can cause a potentially viable market to suffocate from lack of credit. In the process, borrowers who may otherwise be creditworthy are denied loans and have nowhere else to turn because of the lack of entry by competitive lenders.

CRA has been effective in addressing these problems by facilitating coordination and assuring banks that they will not be the lone participants in thinly traded markets. The statute and its regulations have produced positive information externalities that allow all lenders, whether or not covered by CRA, to better assess and price for risk. By conferring an affirmative and continuing obligation on banks to help meet the credit needs of all the neighborhoods they serve, CRA has not only prompted banks to be more active lenders in LMI areas, but also important participants in multisector efforts to revitalize communities across the country.

Because of CRA, banks have made good strides in LMI markets. They have taken numerous steps, including establishing loan products geared to LMI borrowers; entering loan pooling arrangements; undertaking lending consortiums; and partnering with local groups, community development corporations and community development financial institutions (“CDFIs”) to break down barriers that impede the efficient flow of capital into LMI communities.

The numbers show significant benefits. One accounting and tax advisory firm estimated that the banking sector was the source of 85% of the $10 billion in capital committed to housing tax credit investments in 2012.[14] When bank investors were surveyed about why they were so attracted to housing tax credit investments, they said the principal motivation was their obligations under the CRA investment test.[15] Between 2009 and 2018, banks issued more than $2.2 trillion in home loans, and more than $564 billion in small business loans, to LMI borrowers and communities, and provided at least $2 trillion in community development financing between 1996 and 2017.[16]

CRA and its regulations do not, however, focus on people and neighborhoods of color the way they focus on LMI people and neighborhoods. There are some limited race-conscious provisions,[17] but explicit consideration of race in CRA evaluations and other aspects of CRA is more notable for its omission than inclusion.

B. Successfully Addressing the Continuing Consequences of Discrimination Requires a More Race-Conscious CRA

With a structure focused on income and not race, CRA has not sufficiently addressed the continuing extraordinary financial disparities that are the direct result of persistent and systemic racial bias. For example, according to 2019 survey data, White families had a median wealth of $188,200 and a mean wealth of $983,400; Black families’ median and mean wealth was $24,100 and $142,500, respectively. That is less than 15% of White families. Hispanic families’ median and mean net worth was $36,100 and $165,500.[18] Rates of minority homeownership overall have changed little in the past 25 years, while homeownership rates for African Americans have regressed to levels lower than when the Fair Housing Act was passed in 1968.[19]

The nation’s regulators have acknowledged the outsized racial gaps that CRA has not closed. In 2018, former FDIC chairman and current board member Martin Gruenberg recognized the successes of CRA, but also the significant disparities that remain for communities of color.[20] Both the Republican-appointed former OCC Acting Comptroller Brian Brooks[21] and the Democratic-appointed current Acting Comptroller Michael Hsu have recently cited the continuing challenges facing communities of color.[22]

The Fed, in a 2020 advance notice of proposed rulemaking that is discussed extensively in this paper, makes clear that CRA is a policy tool intended to address this longstanding problem:

CRA invests the Board, the FDIC, and the OCC with broad authority and responsibility for implementing the statute, which provides the agencies with a crucial mechanism for addressing persistent systemic inequity in the financial system for LMI and minority individuals and communities. In particular, the statute and its implementing regulations provide the agencies, regulated banks, and community organizations with the necessary framework to facilitate and support a vital financial ecosystem that supports LMI and minority access to credit and community development.[23]

CRA’s effectiveness at increasing access to credit and to the financial market for LMI individuals indicates that it can be a powerful and effective tool for increasing access among underserved borrowers.[24] But the efficacy has been largely tied to those measures that are explicitly discussed and considered by regulators as part of the CRA examination framework.[25] Lacking an extensive and direct focus on race, CRA’s benefits are often distributed in a manner that is not targeted at ameliorating racial inequity and inequality that exists due to past and, to a lesser degree, continuing, discrimination. To successfully address the legacy of discrimination in the United States’ banking system, CRA’s regulatory framework must be modified to explicitly consider banks’ lending, service and community development activities from the perspective of race.

C. Summary of How CRA Regulations Should Be Made More Race-Conscious

This paper discusses several race-conscious ways that CRA regulations should be modified and explains why they are consistent with the Equal Protection Clause of the United States Constitution. In many cases, we build on the Fed’s 2020 Advance Notice of Proposed Rulemaking (ANPR)[26] by offering race-conscious approaches that are analogous to the Fed’s LMI-focused proposals. These would complement, not replace or in any way diminish, what the Fed proposes.

We summarize the proposals here. In subsequent sections we describe them in greater detail and explain why they are lawful after setting forth the constitutional framework. The final section demonstrates that regulators already possess authority to adopt these race-conscious proposals, i.e., that statutory amendment is not needed.

We first propose significant ways of increasing the collection, calculation and reporting of data about lending to people and neighborhoods of color. The data include metrics about banks’ performance in their assessment areas, as well as community and geographic benchmarks. The benchmarks convey the racial demographics of the assessment areas and of lending activity by all institutions in them (that is, by the market as a whole). They concern retail lending (mortgage, small business, small farm and consumer), branch locations and community development financing (i.e., loans and investments). This information would increase public, examiner and even banks’ own understanding of banks’ success, or lack thereof, in serving people and neighborhoods of color, and the context in which banks operate, termed the “performance context.” These measurements match the Fed’s informational proposals about LMI people and neighborhoods.

To further enhance regulatory understanding of the racial components of banks’ varying performance contexts, we next propose dedicating research positions to studying exactly that. This is intended to overcome inconsistency and lack of depth in efforts to understand performance context attendant to the current dependence on individual examiners whose expertise does not lie in this type of research. This is a problem for racial and non-racial elements of performance context.

Banks may not arbitrarily exclude LMI neighborhoods from their assessment areas. But no such express prohibition applies to neighborhoods of color, only a prohibition against unlawful discrimination in delineating an assessment area. We explain why arbitrary exclusion should be barred for both, so that banks are compelled to pay greater attention to meeting the needs of neighborhoods of color that are fairly considered part of their local communities.

We then propose how race should be incorporated explicitly into CRA evaluations themselves. This would apply when, as to specific racial groups, geographic markets and products, evidence shows that access to credit is less than it would be absent the impact of past and/or present discrimination.

For retail lending, we present two alternatives. The better one is to establish threshold levels of lending to people and neighborhoods of color that banks must reach to obtain a presumption of satisfactory on this part of the evaluation, with a constitutionally important exception for falling short despite a good faith effort. Quantitative performance ranges could also be established to generate recommendations for each rating. The less effective but still beneficial alternative is to give examiners discretion to treat strong performance relative to benchmark-based aspirational goals as a plus factor in assigning a rating, with no negative consequences for failing to meet those goals.

With respect to the evaluation of retail services and community development financing and services, we explain how qualitative consideration should be given to race using the plus factor design. Metrics would be involved in some respects, but examiners would use their judgment with the help of guidelines to promote consistency to interpret and decide how much weight to give the numbers.

Evaluations should also affirmatively review whether neighborhoods of color have been arbitrarily excluded from a bank’s assessment areas, consistent with the proposed addition of that prohibition. And when certain assessment areas are selected for a full-scope review in an evaluation (to the extent the distinction between full- and limited-scope reviews is retained), racial demographics should be added to the list of factors considered in deciding which assessment areas to select.

Finally, we propose that when a bank chooses to be evaluated under a strategic plan approved by its regulator (an option in lieu of the regular evaluation procedure), it must conduct outreach to organizations serving neighborhoods of color.

II. Constitutional Framework for Analyzing Race-Conscious Government Programs

A. Strict Scrutiny: What it Means and When It Applies

When a governmental entity acts on the basis of a racial classification and the action is challenged in court as violating the Constitution’s Equal Protection Clause, the propriety of the government’s action is generally reviewed using a strict scrutiny standard. This can include an isolated government action or a whole program. Under strict scrutiny, the government’s action is appropriate only if the statute or regulation giving rise to it is “narrowly tailored” to meet a “compelling governmental interest:”

When race-based action is necessary to further a compelling government interest, such action does not violate the constitutional guarantee of equal protection so long as the narrow-tailoring requirement is also satisfied.[27]

Strict scrutiny is the most exacting standard of judicial review. The Supreme Court has squarely rejected the proposition that “benign” racial classifications favoring traditionally disadvantaged groups should be subject to a less demanding standard of review.[28]

For some classifications, including those based on gender, courts employ intermediate scrutiny, requiring that the law be “substantially related” to or “substantially further” an “important” government interest.[29]

For classifications not based on suspect grounds, courts employ rational basis review, under which they ask whether the regulation is rationally related to a “legitimate” government interest.[30]

The Supreme Court has made clear that the application of strict scrutiny varies based on context:

“Context matters when reviewing race-based governmental action under the Equal Protection Clause. . . . Not every decision influenced by race is equally objectionable, and strict scrutiny is designed to provide a framework for carefully examining the importance and the sincerity of the reasons advanced by the governmental decisionmaker for the use of race in that particular context.”[31]

Of great importance to consideration of race in CRA context, courts recognize that the government has a compelling interest in remedying the effects of past or present discrimination.[32] This is especially true for discrimination either caused by the government (e.g., through facially discriminatory laws, regulations or practices), or in which the government is a “passive participant” (e.g., distributing funding in a market that suffers from discrimination in a way that does not address or remedy that discrimination).[33] The target must be specific, though, because “claims of general societal discrimination—and even generalized assertions about discrimination in an entire industry—cannot be used to justify race-conscious remedial measures.”[34]

The government must also have a “strong basis in evidence” to support its compelling interest. When the interest is addressing discrimination, this means evidence that discrimination has occurred and requires remedial action.[35] The government must identify evidence of current exclusion from the precise activity or area at issue that is the result of discrimination, demonstrating why a race-conscious remedy is necessary to eliminate that exclusion.[36]

Assuming the government can establish a compelling interest, it must then demonstrate that the action, program or law at issue is narrowly tailored to meet that interest. The inquiry is intended “to ensure that the means chosen ‘fit’ the compelling” interest such that “there is little or no possibility that the motive for the classification was illegitimate racial prejudice or stereotype.”[37] Factors courts consider when determining whether a law is narrowly tailored include whether the law is over- or under-inclusive; the burden created on third parties; the duration of the law (or whether it includes provisions for reevaluation); how “flexible” the program is (including how individualized the consideration given to potential beneficiaries is, provisions allowing for the withholding or granting of benefits for non-race-conscious reasons, and provisions allowing non-minorities to receive the relevant benefit in certain circumstances); and whether the government has considered or previously tried race-neutral approaches and found them inadequate.[38] These factors function as safeguards to assure that race is not used in a manner that exceeds constitutional legitimacy. Being on the wrong side of the analysis on just one of them is likely enough for a court to find a use of race unconstitutional.

B. Principles Taken From Application of Strict Scrutiny to Race-Conscious Programs in Other Contexts

Although strict scrutiny is an exacting standard, it is not inherently or necessarily fatal to the laws or regulations being evaluated.[39] The courts have upheld race-conscious programs in a variety of contexts, including higher education admissions and government contracting, in the past 20 years. We next describe some of these cases to discern principles that support or cabin the potential explicit consideration of race under CRA.

Government Contracting

The most helpful area of case law for a race-conscious CRA likely lies in government contracting affirmative action cases. For more than 30 years, legal challenges have been raised relating to a variety of government programs intended to increase the proportion of minority-owned businesses that receive (sub)contracts for government-funded construction projects. These programs generally provide some form of preference to minority-owned businesses during the contracting process and have been justified using a variety of more and less successful methods. The central Supreme Court decisions in this area are City of Richmond v. J.A. Croson Co. (Croson)[40] and Adarand Constructors, Inc. v. Peña (Adarand).[41]

Croson involved an ordinance adopted by Richmond, Virginia, requiring 30% of construction contracts to be awarded to minority-owned businesses. There were some facts and findings supporting the program; notably, Congress had determined 20 years prior that racial discrimination was common in construction, and Richmond had found that minority-owned businesses received less than 1% of construction contracts, despite the fact that the city’s population was 50% minority.[42]

The Supreme Court found that was insufficient to justify Richmond’s race-conscious program. The Court observed that the city had not determined the number or proportion of minority-owned businesses in Richmond’s construction market and had no evidence that qualified minority contractors had ever been passed over for contracts.[43] Thus, the city could not say how many contracts minority enterprises would be getting if discrimination exerted no influence, making the 30% figure arbitrary. The problem, the Court found, is that “generalized assertions about discrimination in an entire industry” do not permit properly tailored remedies.[44] That is, a general finding that “there has been past discrimination in an entire industry provides no guidance for a legislative body to determine the precise scope of the injury it seeks to remedy. It has no logical stopping point.”[45]

The Court was also troubled by the inclusion of minority groups against which there was “absolutely no evidence of past discrimination . . . in any aspect of the Richmond construction industry.”[46] This suggested to the Court that “perhaps the city’s purpose was not in fact to remedy past discrimination.”[47]

Seven years later, Adarand, involved a remedial federal program in which prime contractors were given a financial incentive to hire subcontractors certified as small businesses controlled by “socially and economically disadvantaged individuals.” The program included a presumption that minorities were socially and economically disadvantaged.[48] Although the Supreme Court did not decide the merits of Adarand, its discussion in that case has been of critical importance in the years since. Among other elements of the program, the Court specifically discussed the fact that non-minorities were given the opportunity to prove their social disadvantage,[49] and that the presumptions of social and economic disadvantage were rebuttable.[50] This has been an important feature of race-conscious government contracting programs that have survived strict scrutiny in lower courts.[51]

When remanding the case to the Court of Appeals, the Supreme Court indicated that the lower court should “address the question of narrow tailoring” by asking, among other things, “whether there was any consideration of the use of race-neutral means to increase minority business participation in government contracting” and “whether the program was appropriately limited such that it will not last longer than the discriminatory effects it is designed to eliminate.”[52] The Court also focused on the lack of clarity around whether individualized inquiries were necessary to determine economic disadvantage, and how such a showing would be made.[53]

From these cases and lower court cases that followed, a few key considerations emerge.

First, because the compelling interest in contracting cases has to do with remedying the effects of discrimination, the program must be designed and tailored in a manner that is tied to discrimination that is identified with meaningful specificity. This means that broad societal prejudice is insufficient to support an affirmative action program; instead, there must be some evidence of racially motivated discrimination within the economic sector (and geography) in which the program will operate, and this evidence must rise above general assertions of the existence of discrimination in an industry or sector.[54]

The necessary showing can be made with a combination of statistical and anecdotal evidence. The statistical evidence should go beyond simple bottom-line disparities in outcomes for racial groups, such as different rates of approval for mortgage applications. It might do so by, for example, controlling for factors that are relevant to mortgage approval through a regression analysis.[55] Anecdotal evidence might take the form of, for example, interviews with individuals about their personal experiences.[56] If statistical disparities are large enough — the Supreme Court has used the terms “significant” and “gross” — they may provide sufficient evidence of discrimination to demonstrate the government’s requisite compelling interest without the addition of anecdotal evidence.[57] Statistical evidence is the more important of the two.[58]

Second, programs that involve aspirational goals or flexible targets, rather than quotas, meet with more favor from the courts. A program oriented toward achieving full and fair participation (participation that would reflect expected participation absent discrimination and its effects) is permissible—but a program that requires a certain level of minority participation to be achieved, regardless of how feasible that may be and without regard for any good-faith efforts that may have failed, will likely be considered too inflexible to withstand scrutiny.[59]

Third, the less of a burden caused to third parties outside of the race intended to benefit from a program, the more likely the program is to withstand constitutional scrutiny. Flexibility in the program such that an individual is not penalized or prevented from receiving a benefit despite attempts to comply with the program will tend to support the validity of that program (for example, waivers for good faith attempts to hire minority subcontractors, or individualized mechanisms to qualify for or be disqualified from an affirmative action program, which also speak to flexibility). On the other hand, if a purportedly flexible program effectively operates as a categorical grant or denial of a benefit based on a person’s race, the program is unlikely to withstand scrutiny.[60]

Fourth, it is critically important that the governmental body putting forth the race-conscious program has considered the feasibility of race-neutral alternatives to meet its compelling interest, potentially including attempting race-neutral solutions without sufficient success. This overlaps with the requirement (under the compelling interest part of the analysis) of demonstrating the necessity of a race-conscious approach, lending credibility to the government’s assertion that taking race into account is necessary to remediate the effects of racial discrimination.

Higher Education Admissions

Unlike in contracting, the government interest that frequently undergirds affirmative action in the educational context, including admissions to institutions of higher education, is an interest in diversity itself, an end that has been recognized by courts as compelling only in limited circumstances. This difference has significant ramifications for the application of the strict scrutiny standard. Though some are less relevant to the CRA context in which ameliorating the effects of discrimination is the animating goal, certain elements of these cases are nevertheless important.

Similar to the concept of flexibility in contracting cases, flexibility and individual consideration are paramount in the educational context. Programs that include numerical quotas or caps (even if they are based on local demographics) are highly suspect. Courts have shown serious skepticism that the goals of institutional diversity require quotas and have found that quotas designed to reflect local demographics are not sufficiently related to the interests institutional diversity is intended to serve.[61]

On the other hand, programs that focus on individual consideration and take a holistic view both of institutions and applicants to those institutions meet with significantly more favor. In particular, programs that consider race as one of many factors, without recourse to a quota or inflexible point systems (i.e., a method that gives an automatic and pre-determined, often numerical, boost to applications from people of color to make them more competitive[62]), are supported in court decisions.[63] As the Supreme Court explained in upholding the University of Michigan Law School’s race-conscious admissions policy in Grutter v. Bollinger in 2003:

When using race as a “plus” factor in university admissions, a university’s admissions program must remain flexible enough to ensure that each applicant is evaluated as an individual and not in a way that makes an applicant’s race or ethnicity the defining feature of his or her application. The importance of this individualized consideration in the context of a race-conscious admissions program is paramount.[64]

Analogously, it is reasonable to expect that a race-conscious CRA requiring a particular number or percentage of loans be made to minority borrowers, or in minority areas, will not be viewed as sufficiently holistic or flexible; likely neither would a system that automatically boosts a CRA rating in a predetermined manner based on specific race-related lending activities. Instead, considering race in the CRA context is more likely to be permissible if minority lending is considered as one of many factors intended to determine how successfully a financial institution is meeting the needs of its entire community—including borrowers and neighborhoods of color, and in a non-formulaic way.

COVID Relief Programs

Strict scrutiny for programs based on race extends well beyond government contracting and higher education admissions.[65] Although the application of strict scrutiny varies — including to reflect the nature of the government interest at stake — many of the considerations more relevant to CRA carry over across contexts.

In recent months, race-conscious programs arising from COVID relief efforts related to Small Business Administration (SBA) grants and forgiveness of Department of Agriculture (USDA) loans, for example, have been subjected to strict scrutiny by the courts. In both, the program at issue was found not to satisfy strict scrutiny (or to be unlikely to do so), but the context of the cases and details of the decisions help underscore the lessons taken from other contexts and provide additional guidance for when race-conscious programs are permitted.

Vitolo v. Guzman[66] concerned a challenge to COVID relief for minority-owned restaurants, a $29 billion program passed this year as part of the American Rescue Plan Act. For the program’s first 21 days, Congress limited grants to priority applicants — restaurants owned or controlled at least 51% by women, veterans or socially and economically disadvantaged people.[67] Other applicants would not receive grants if the funds ran out in that time. The program includes a rebuttable presumption that certain groups are socially disadvantaged: Black, Hispanic, Native, Asian Pacific, and Subcontinent Asian Americans all receive this presumption.[68] Those not entitled to the presumption can only be deemed socially disadvantaged by demonstrating that they have experienced discrimination by a preponderance of the evidence.[69]

The Sixth Circuit granted a preliminary injunction against the priority period. It held that the government had not adequately shown a compelling interest. In the court’s view, the government relied too generally on “societal discrimination against minority business owners” without “identify[ing] specific instances of past discrimination”[70] It also found inadequate the government’s evidence of intentional discrimination against many of the groups who received the presumption of social disadvantage.[71]

The court was also not satisfied as to narrow tailoring. Of central importance, it held that in this context, the presumption of social disadvantage effectively guaranteed eligibility for minority-owned businesses and ineligibility for non-minority owned businesses (unless women- or veteran-owned).[72] It also cited “obvious race-neutral alternative[s]” in determining that the program was both over-and under-inclusive.[73]

Vitolo is a reminder of the necessity for careful and thorough documentation of discrimination specific to an economic sector or a particular activity to properly support a race-conscious program and to properly tailor the remedial program. It also underscores the importance of ensuring flexibility in the program by preventing any program element from operating as an automatic grant or denial of eligibility.

Wynn v. Vilsack[74] also addressed a program in the American Rescue Plan Act, this time one forgiving federal loans owed by “socially disadvantaged farmers and ranchers.” It emphasizes the importance of considering other remedial efforts that may have altered the playing field and ensuring that the program is flexible and responsive to actual conditions on the ground.

The court recognized the “dark history of past discrimination against minority farmers” by the USDA.[75] But it found that this did adequately support a compelling interest because the evidence did not account for federal attempts to remedy that discrimination and consider whether they had been successful.[76] Although the government argued that prior remedial measures had fallen short, the court determined that the presently existing barriers the government pointed to — for example, weaker financial condition of Black farmers pre-pandemic, disparities in default rates, and weaker credit profiles — were not adequately shown to be the effects of discrimination.[77] Still, the court recognized that the government might be able to make out a compelling interest later in the case when the evidentiary record was further developed, either with evidence that attempts at remediation had in fact been insufficient to remedy past discrimination, or that the government remained a passive participant in discrimination.[78]

The court’s biggest concern was narrow tailoring. The program did not use a presumption of social disadvantage or require economic disadvantage. Rather, “[t]he debt relief provision applies strictly on racial grounds irrespective of any other factor.”[79] The court called this a “rigid, categorical, race-based” program and “the antithesis of flexibility,”[80] and it was fatal. It also objected that the loan forgiveness program “fail[ed] to provide any relief to those who suffered the brunt of the discrimination” that the government had identified, i.e., people who could not get a USDA loan in the first instance or who no longer had one because of discrimination.[81] As such, the program was inflexible and failed to address the discrimination that the government relied on for its compelling interest.

The lessons from Vitolo and Wynn must be taken seriously, but as discussed in this paper, CRA involves a very different type of program and context than these COVID relief measures. That is highly consequential for a strict scrutiny analysis.

C. It Is Likely, Though Not Certain, That Courts Would Apply Strict Scrutiny If Regulators Consider Race When Determining CRA Ratings

If CRA regulations are amended to take into account the race of loan recipients when determining an institution’s CRA rating, it is likely that a court hearing a challenge to those regulations will evaluate the reliance on race using strict scrutiny. There are two significant distinctions, however, that could lead to a different standard of review or, at a minimum, would likely affect how strict scrutiny is applied.

First, unlike many contexts in which the government takes race into account when acting, it is not the race of the would-be recipient of the benefit that figures in the government’s provision of a direct benefit. In the contracting context, the government may decide whether to provide contracts and funds based on minority subcontractors who will be hired on to participate in the project. In the educational context it is the race of the would-be student herself that is the relevant criterion. In the context of CRA, the race of a financial institution’s owners or top managers would be immaterial. A good CRA rating could be attained without regard to the race of the top shareholder, the CEO or anyone else responsible for the institution.

Second, unlike the race-conscious programs at issue in the majority of case law in this area, CRA does not deal in limited resources or limited benefits. There are finite amounts of government contracts and contracting dollars available; schools cannot admit all comers. In this way, traditional affirmative action-type programs involve a zero-sum game: if one business is awarded a contract, it is at the expense of another business that might have received the contract instead. In contrast, good CRA ratings are an unlimited resource: there is no reason every financial institution cannot receive a satisfactory or outstanding rating. Put another way, one financial institution receiving a good CRA rating does not burden another financial institution in the “if you get it, I cannot,” zero-sum sense of burden.

These considerations could support a conclusion that strict scrutiny does not apply to the consideration of race in arriving at CRA ratings. Strict scrutiny is often discussed in connection with programs that differently benefit and burden people based on race and create “racial classifications.”[82] Whether race-conscious ratings would allocate benefits or burdens based on race, or could properly be described as racial classifications, are fair questions to which Equal Protection jurisprudence does not provide clear answers. If strict scrutiny did not apply, CRA would be evaluated under the much more permissive rational basis standard of review.

Nonetheless, in light of broad statements by the Supreme Court and lower federal appellate courts about the need for strict scrutiny analysis any time a government acts on the basis of race (all governmental uses of race are subject to strict scrutiny)[83] and the current makeup of the Supreme Court, the more likely outcome is that making race a component of CRA ratings and requirements would be reviewed under a strict scrutiny standard. Because a bank would have a better chance to receive a good rating based on how it performs in connection with the race of other individuals, we expect courts would look to these expansive statements and find strict scrutiny triggered. For purposes of this article, we presume so.

Rather than holding that rational basis review applies, a court more likely would make use of the distinctions between CRA and other contexts to shape the form strict scrutiny takes. As the Supreme Court has indicated, strict scrutiny varies by context; this variability is reflected in how the doctrine is applied in a given case. The fact that, due to the unlimited nature of the benefit, any burden on third parties is significantly curtailed if not eliminated makes it more likely that CRA would withstand strict-scrutiny review. And the fact that it is not the race of the beneficiary that is relevant in a CRA rating likewise should improve the program’s chances of passing strict scrutiny.

D. Strict Scrutiny Should Not Apply to Regulators’ Collection and Publication of CRA Information About Race

Regulatory collection and publication of data and other information related to minority lending, on the other hand, should not be subject to strict scrutiny. Such collection and reporting is common and its importance is well established. Reports that deal with racial demographics include ones as fundamental as the census itself. Without reporting about race, the government would be significantly hindered in its ability to enforce civil rights and other important statutes and to make sound policy decisions.

The federal Home Mortgage Disclosure Act (HMDA) is the most obvious example of such reporting in the lending context. Mortgage lenders must collect and report to the government application-level information that includes applicant race and census tract demographic information; the government publishes much of it, including the name of the lender.[84] This serves many important purposes. As a recent CFPB report states, “HMDA data are used to assist in determining whether financial institutions are serving the housing credit needs of their local communities; facilitate public entities’ distribution of funds to local communities to attract private investment; and help identify possible discriminatory lending patterns and enforce antidiscrimination statutes.”[85] There are many other examples of the government gathering and publishing data regarding race.[86] Indeed, the Office of Management and Budget publishes guidelines for how to collect and report race-related data.[87]

Gathering and publishing data about race, and publishing reports based on that data, do not amount to or directly affect the dispersal of government benefits. Nor do they entail the use of race in a manner that somehow burdens the rights of a racial group. In other words, they do not constitute the government “acting on the basis of race” in a manner that implicates strict scrutiny. This distinguishes them — by far — from the types of racial classifications by the government that has implicated strict scrutiny review by the courts. It would be good policy to make CRA reporting about race more robust as recommended below, and it should not cause any constitutional concern.

III. Regulators Can Increase Their Understanding of the Role of Race in a Bank’s Performance Context Without Triggering a Heightened Standard of Judicial Review

Banks operate in local communities which differ in many ways that are relevant to a community’s credit needs. In regulatory parlance, this is part of the “performance context.” This section describes important ways regulators can, without triggering strict scrutiny or any other heightened standard of review, systematically improve their understanding, and the public’s understanding, of the racial components of a bank’s performance context. These approaches should not be controversial from a constitutional perspective.

A. Expanding the Fed’s Proposal to Include More Information Regarding Race

The Interagency Q&A Regarding CRA defines performance context as “a broad range of economic, demographic, and institution- and community-specific information . . . .”[88] It includes:

(1) Demographic data on median income levels, distribution of household income, nature of housing stock, housing costs, and other relevant data pertaining to a bank’s assessment area(s);

(2) Any information about lending, investment, and service opportunities in the bank’s assessment area(s) maintained by the bank or obtained from community organizations, state, local, and tribal governments, economic development agencies, or other sources;

(3) The bank’s product offerings and business strategy . . .;

(4) Institutional capacity and constraints, including the size and financial condition of the bank, the economic climate (national, regional, and local), safety and soundness limitations, and any other factors that significantly affect the bank’s ability to provide lending, investments, or services in its assessment area(s);

(5) The bank’s past performance and the performance of similarly situated lenders;

(6) The bank’s public file . . . and any written comments about the bank’s CRA performance . . .; and

(7) Any other information deemed relevant by the [regulator].[89]

Performance context is reviewed in CRA examinations “to calibrate a bank’s CRA evaluation to its local communities.”[90] This is very much in line with the statutory focus on local communities.[91]

i. Retail Lending

For LMI, the Fed proposes to move toward more systematic use of the retail lending performance context in examinations by establishing a series of quantitative “benchmarks.” The benchmarks would tell regulators what portion of the potential credit recipients in an assessment area are LMI and in LMI areas, and what portion of actual credit recipients are LMI and in LMI areas.[92] They generally parallel information currently termed “comparators” and used by examiners, but in a less structured way than the Fed is now proposing.[93]

There are parallel race-related data points for all of these benchmarks, but the Fed does not currently calculate or use them as comparators, or propose to do so as benchmarks. Calculating race-based benchmarks, alongside the LMI ones, would significantly improve regulators’ understanding of banks’ varying performance contexts.

To be more specific, the nature of each LMI benchmark in the Fed’s proposal has three components: community or market; geographic or borrower; and line of business:

Community benchmarks concern the demographics of an assessment area. Market benchmarks concern the demographics of loan recipients aggregated across all lenders.

Geographic benchmarks compare an assessment area’s LMI census tracts to the assessment area as a whole. Borrower benchmarks compare an assessment area’s LMI residents, small businesses, small farms and loan recipients to those of the assessment area as a whole.

There are sets of benchmarks for each of four lines of business: mortgage, small business, small farm and consumer.

This results in sixteen benchmarks, four for each line of business. In mortgage, for example, the community/geographic benchmark would be the percent of owner-occupied homes in an assessment area’s LMI census tracts. The market/geographic benchmark would be the percent of mortgages made in the assessment area’s LMI tracts by all lenders. The community/borrower benchmark would be the percent of families in the assessment area that are LMI. Finally, the market/borrower benchmark would be the percent of mortgages made by all lenders in the assessment area to LMI borrowers.

Identifying counterparts based on race instead of LMI is straightforward. Again using mortgage to illustrate, the community/geographic benchmark would be the percent of owner-occupied homes in an assessment area’s census tracts that are either majority- or disproportionately minority.[94] The market/geographic benchmark would be the percent of mortgages made in the assessment area’s majority- and disproportionately minority tracts by all lenders. The community/borrower benchmark for mortgage would be the percent of families of color in the assessment area. The market/borrower benchmark would be the percent of mortgages made by all lenders in the assessment area to borrowers of color.

The benchmarks would provide reference points for a bank’s own lending. To allow for comparison, the Fed proposes to calculate a geographic distribution metric and a borrower distribution metric for each of a bank’s major product lines.[95] The geographic metric would be the number of the bank’s loans in LMI census tracts divided by the total number of its loans in the assessment area. The borrower metric would be the number of its loans to LMI borrowers divided by the same figure.[96]

Again, there are clear analogues based on race: the number of loans in majority- and disproportionately minority census tracts divided by the total number of loans, and the number of loans to minority borrowers divided by the total number of loans. Adding these metrics would provide important information about a bank’s success, or lack thereof, in extending credit to people and neighborhoods of color.

ii. Retail Services (Branch Locations)

For large banks, the Fed also proposes branch distribution benchmarks for retail services. Three are community benchmarks: the percentage of census tracts, households and total businesses in an assessment area by tract income level (low, moderate, middle, upper and unknown).[97] The fourth is a market benchmark: the percentage of all the bank branches in the assessment area by tract income level.[98]

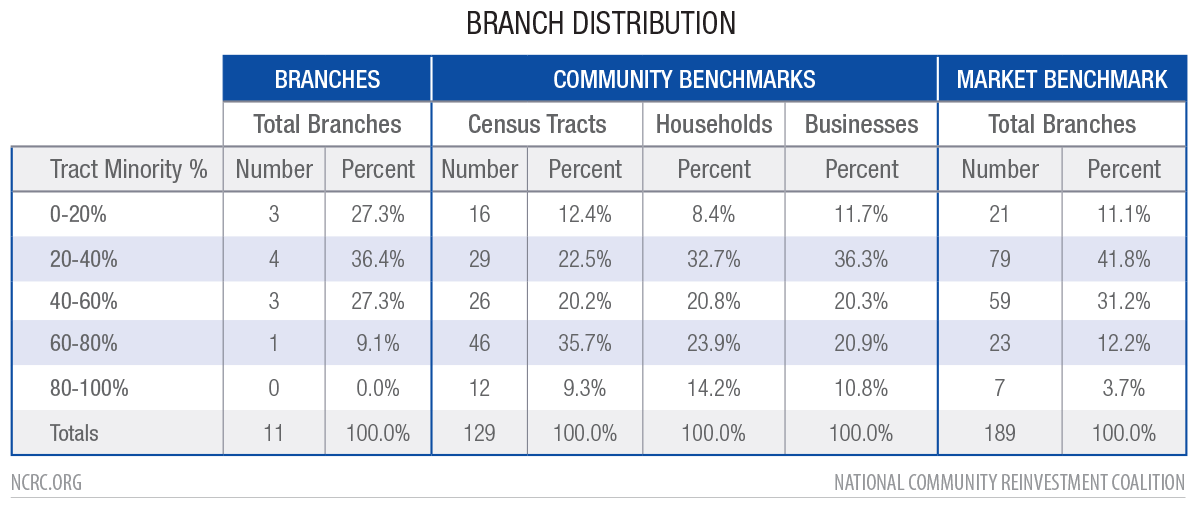

Like the retail lending benchmarks, these branch distribution benchmarks are easily adjusted to address race. Instead of dividing census tracts by five income levels, they could be divided by tract minority percentage (e.g., 0-20%, 20-40%, etc.). One community benchmark would be the percentage of census tracts in the assessment area that are 0-20% people of color, etc.; one would be the percentage portion of households in tracts that are 0-20% people of color, etc.; one would be the percent of businesses that are in tracts that are 0-20% people of color, etc. And the market benchmark would be the percentage of the assessment area’s bank branches in census tracts that are 0-20% people of color, etc. Using hypothetical numbers, and incorporating a hypothetical bank’s own branch distribution as the Fed proposes to do with respect to LMI, all of the branch distribution benchmarks might be combined in one chart as follows:[99]

iii. Community Development Financing

The Fed also proposes community development financing metrics and benchmarks for large retail banks. The metric would be the dollar amount of a bank’s community development loans and investments in the assessment area divided by its deposits in the assessment area.[100]

There would be a local and a national benchmark. The local benchmark would be the total of all large retail banks’ community development loans and investments in the assessment area divided by their collective deposits in the assessment area. There would be two variations of a parallel national benchmark, depending on whether the assessment area is in a metropolitan or nonmetropolitan area. It would be all large retail banks’ community development loans and investments in all metropolitan (or nonmetropolitan) areas in the country divided by their deposits in those areas.[101]

We propose a complementary variation of the community development financing benchmarks and metric focused on neighborhoods with a substantial population of color. The numerator for the benchmark calculations would be community development loans and investments by large retail banks in majority- and disproportionately minority census tracts of the assessment area (or metropolitan/nonmetropolitan parts of the country). The denominator would remain all deposits, whether in the assessment area or metropolitan/nonmetropolitan parts of the country. The community development financing metric would be the bank’s community development loans, and investments in the same tracts in the assessment area, divided by all of its deposits in the assessment area.

The metrics and benchmarks would provide a more precise understanding of how effectively community development funds are reaching neighborhoods of color, not just assessment areas as a whole. The ones proposed by the Fed are important to see whether local funds are being diverted to entirely distinct regions, but the high-level picture they paint would be incomplete without others that zoom in on the neighborhoods with a heightened need for the funds.

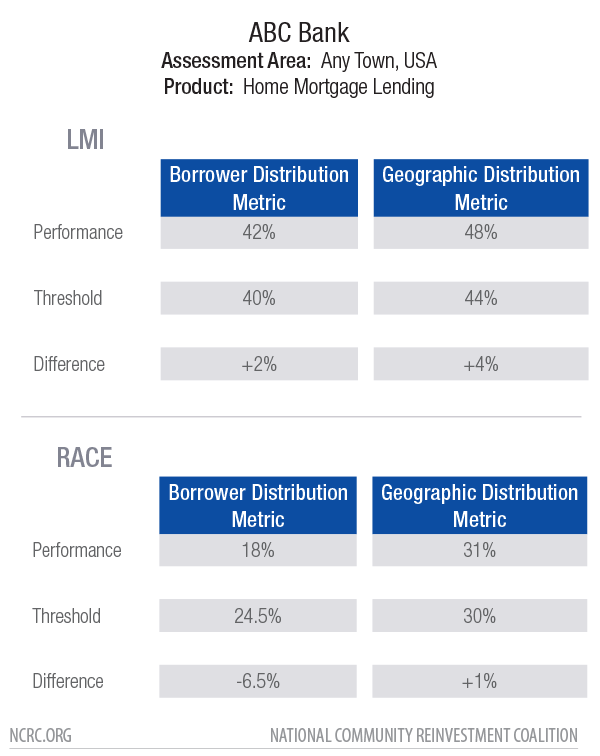

iv. Dashboards for Banks

The Fed proposes to provide an online portal for banks with dashboards showing some of the LMI information for each of a bank’s assessment areas and product lines.[102] For each of a bank’s major lines of business, the proposed dashboard would incorporate the calculation of “thresholds” (based on the benchmarks) used to determine whether the bank receives a presumption of a satisfactory rating.[103] How parallel race-based benchmarks and metrics could similarly and properly be incorporated in examinations is discussed supra in Section V.D. Here we only address the more limited step of presenting the racial information by dashboard in a way that is easily understood, and useful for banks and regulators alike.

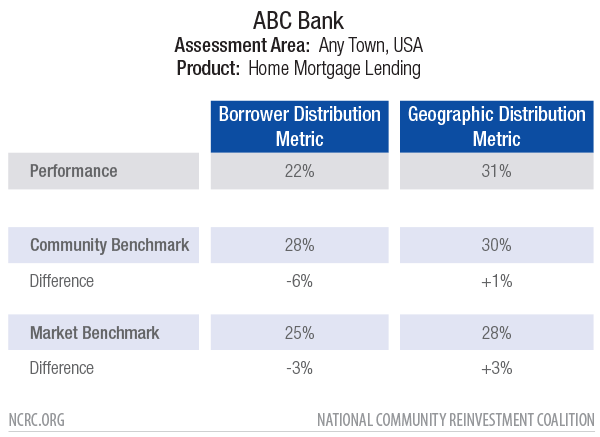

For a given line of business, the dashboard could show: (1) the borrower distribution metric; (2) the two borrower benchmarks (community and market)[104]; (3) the geographic distribution metric; and (4) the two geographic benchmarks (also community and market). As with the LMI proposal, updating the figures based on data for the prior quarter or year would make them reflect not only the local community, but also “changes in the local business cycle.”[105]

The dashboard might look like:

The dashboard might look like:

In this hypothetical example, the dashboard would quickly and clearly convey that the bank’s mortgage lending in neighborhoods of color does not stand out as good or bad, but that it is having difficulty reaching borrowers of color. This information would help guide the bank in assessing its strategies for serving its entire community, and examiners in reviewing the bank’s responsiveness to the entire community.

The Fed proposes to publish the community development financing benchmarks on publicly available dashboards “to provide the most transparency and clarity to banks to allow them, and the public, to track their performance.”[106] That should include the additional benchmarks proposed above focused on funding in neighborhoods of color. Each large retail bank’s own dashboard should also include its own metrics in an easily understood format, so it can tell how well it is performing relative to its peers.

v. Making Data Available to the Public

In addition to ascertaining the data points concerning race and making at least some of them available on banks’ dashboards, regulators should publish the data as part of the public portion of each written CRA performance evaluation.[107] This would allow all stakeholders and interested members of the community to better understand how effectively the examined institution, and the market as a whole, are serving the needs of individuals and neighborhoods of color (which is necessary to understand how well they are serving the credit needs of their whole community). This information would be an invaluable complement to the longstanding public disclosure of HMDA data about mortgage lending, and the forthcoming public disclosure of small business lending data regarding race under section 1071 of the Dodd-Frank Act.[108]

The Massachusetts Division of Banks already includes similar data in its public CRA evaluations.[109] For example, it has included granular mortgage application information broken out by race and ethnicity, alongside the same data aggregated from all lenders in the assessment area and each group’s percentage of the population (e.g., that the examined bank received 0.9% of its applications from African Americans, that the market as a whole received 1.4% of its applications from African Americans, and that African Americans comprised 2.7% of the population).[110]

B. Dedicating Full Time Research Positions to Studying How Race Affects Performance Context

As the Fed’s ANPR explains, the performance context is not simply the data points discussed above. In addition to more types of quantitative data, it includes qualitative information such as community investment needs and opportunities, and CRA strategies that have proved effective locally. This type of information can be obtained from, for example, interviews with community stakeholders.

Typically, developing an understanding of and writing up the performance context for a CRA exam falls to the assigned examiner. As researchers from the San Francisco Fed explain, this creates problems. First, bank examiners are not researchers, and so there is a skills mismatch between examiners and the task of properly researching and identifying the performance context. Second, because the same or overlapping performance contexts are assessed by different people, they are “likely accessing different data sources, which may create a lack of consistency across exams.”[111] This decentralized structure inevitably diminishes the ability of regulators to gain a deep, comprehensive understanding of the performance context and, consequently, of bank performance.

The San Francisco Fed responded with an approach that can readily be adapted to race. It created a formal partnership across departments, assigning one researcher to work full-time “developing the performance contexts for all CRA exams conducted within the Federal Reserve’s 12th district.”[112] The researcher works with outreach managers across the district to leverage their community contacts. Centralizing development of the performance context this way has “created consistency across exams in terms of data sources and analysis, making it easier to do bank-to-bank or year-to-year comparisons,” and allowing examiners to be more up to date about changes that “affect banks’ CRA activities and opportunities.”[113]

The Fed should adopt a similar approach with respect to race so that its CRA exams are informed by a greater understanding of how race affects community and individual banking needs. Specifically, it should dedicate a full-time research position in each of its twelve districts. Better yet, it should make this a coordinated effort with other federal financial regulators to assure that important knowledge is shared by all and that examinations are consistent. The researchers should focus on, and have expertise regarding, lending to communities and borrowers of color. Such communities should include those that are majority-minority and disproportionately minority for the same reasons discussed earlier in connection with benchmarks and metrics. The researchers would work closely with examiners and any other researchers who, like at the San Francisco Fed, are dedicated to analyzing performance context. The public portion of written CRA evaluations should be augmented to include these more thorough and comprehensive performance context understandings, in addition to information already included. This would extend the benefit from regulators and banks to all stakeholders and the public at large.

A priority for these new research positions should be establishing an information collection project for race like one previously maintained by the San Francisco Fed’s Community Indicators Project, which focused on LMI households and communities. The San Francisco Fed semi-annually surveyed “representatives from banks, nonprofits and community based organizations, foundations, local governments, and the private sector” “to collect insights from community leaders about the conditions and trends affecting low-income households and communities.”[114] The project also incorporated data about employment, education, personal investments, rents and housing. The results were published for the public.

A parallel indicators-type project should be set up to better understand conditions and trends affecting households and neighborhoods of color. It should aim to identify areas in communities of color where banks are not adequately serving lending, banking and community development needs, to the extent those needs are not being met, and approaches that have been successful in meeting them. A project like this is essential so that policymakers, CRA examiners, community stakeholders and the public can thoroughly assess how well banks are meeting CRA’s goal of assuring that the needs of the “entire community” are well-served.

IV. A Compelling Interest Supports the Explicit Consideration of Race in CRA Requirements and Evaluations

As discussed above, the government has a compelling interest that supports taking race-conscious steps to ameliorate the continuing effects of past or present discrimination. This includes assuring that it does not distribute benefits in a manner that perpetuates those effects. These propositions are clear from Supreme Court precedent, and undoubtedly apply to discrimination in lending.

As also noted above, that is not the end of a compelling interest inquiry under strict scrutiny. The validity of the interest must be shown, not just asserted. That is, there must be a “strong basis in evidence” of the need for race-conscious remedial action to address the discrimination. This means robust and focused findings that identify current exclusion, grounded in discrimination, from the precise activity at issue. The evidence must allow a reviewing court to understand why the particular remedy enacted is needed to cure the exclusion. As the Supreme Court has explained:

Proper findings in this regard are necessary to define both the scope of the injury and the extent of the remedy necessary to cure its effects. Such findings also serve to assure all citizens that the deviation from the norm of equal treatment of all racial and ethnic groups is a temporary matter, a measure taken in the service of the goal of equality itself.[115]

This standard is focused on the need for a government response and does not require “definitive proof of discrimination.”[116]

For a national program, the compelling interest may be demonstrated at the national level.[117] Whether, and in what form, the program is justified at the local level is then addressed as part of the narrow-tailoring analysis.[118]

As we now show, there is a strong basis in evidence of the need for race-conscious remedial action in connection with the types of lending covered by CRA. The evidence so demonstrating is much too extensive to describe or cite here. Appendix A to this paper provides references to NCRC publications in this area, which in turn cite extensive work by a number of groups and experts who have contributed to this research and literature over the years. These publications supplement and complement the citations within the body of this paper, which further support the strong basis in evidence.

A. There is Extensive Evidence of Public and Private Discrimination Affecting All Types of Credit Covered by CRA

As discussed above, CRA was created to address the impact of discrimination on US credit and financial markets. Both private and public actors engaged in widespread redlining, building discrimination into the foundation of modern credit markets.

Through much of the twentieth century, the federal government and private lenders denied communities of color access to prime mortgage products, significantly curtailing homeownership opportunities for Americans of color, and allowing discriminatory practices that both stripped wealth from and prevented the accumulation of wealth by residents of neighborhoods of color. In the 1930s, the federal government created the HOLC and the FHA. The HOLC assisted homeowners who were in default on their mortgages and in foreclosure.[119] The FHA provided direct assistance to individuals to finance home purchases and federal insurance to back private mortgage lending.[120]

HOLC and FHA programs expanded access to affordable mortgages, assisting millions of families to obtain the financing needed to own their own homes.[121] But people of color were systematically excluded from these programs from the start.[122] This meant they were also largely excluded from private credit markets, because private lenders depended heavily on government programs.

HOLC surveyed neighborhoods based on lending risk and created Residential Security Maps that graded neighborhoods from A (best) to D (hazardous).[123] Minority presence in a neighborhood systematically led to lower grades; the presence of Black people or other “inharmonious” racial or social groups could lead to a D grade.[124] D-grade neighborhoods were depicted on HOLC maps in red (i.e., redlined), to indicate that lending in those areas was risky and discouraged.[125] These maps were used by the FHA.[126]

In 1939, the FHA outlined its core principles in a piece called “The Structure and Growth of Residential Neighborhoods in American Cities,” which “emphasized the importance of maintaining racial segregation.”[127] The FHA also “gathered extensive data on the racial composition of neighborhoods and instructed financial institutions not to lend to households in integrated or predominantly African American areas.”[128]

Historically redlined neighborhoods continue to face significant hurdles. Wealth,[129] health[130] and many other disparities[131] remain pronounced. The redlining and de jure discrimination of the twentieth century is still felt acutely today, including in credit and financial markets.

Beyond the redlining and official discrimination that began in the 1930s and continued for decades, extensive evidence makes plain that there has been discrimination and disparity in the housing market and in mortgage,[132] refinance[133] and home improvement[134] credit markets. There has been systemic and extensive discrimination in farm credit, including by the United States Department of Agriculture.[135] And there has been discrimination in small business lending.[136] The government has engaged in discrimination explicitly, and the government also has distributed benefits in a manner that is affected by (and sometimes perpetuates) discrimination by private entities.

This discrimination did not end with demise of explicit redlining, or with the passage of the Fair Housing Act in 1968, the Equal Credit Opportunity Act in 1974 or CRA in 1977. Although discrimination may have changed in form from the overt racial policies of much of the twentieth century,[137] discrimination and disparities that are caused or perpetuated on discriminatory lines have not been relegated to the past.[138] Statistical and other evidence remains abundant. Indeed, only last month the US Department of Justice and the OCC announced actions against a bank for redlining Black and Hispanic neighborhoods in Houston.[139]

B. Extensive Evidence Shows that Discrimination and Its Effects Limit Access to Quality Credit for People and Communities of Color

Many have documented the continuing effects of discrimination on the financial markets and on access to credit. Redlining, other forms of discrimination, and their legacy are felt in myriad ways, from disparities in homeownership rates that are worse now than even prior to the passage of the Fair Housing Act,[140] to disparities in wealth and discouragement in the lending process that prevent minority-owned small businesses from having full and fair access to credit.[141] In 2021, all 12 districts of the Federal Reserve System hosted a multipart program called “Racism and the Economy: Understanding the implications of structural racism in America’s economy and advancing actions to improve economic outcomes for all.”[142] Contributors documented how the continuing effects of discrimination influence housing,[143] entrepreneurship and business lending,[144] education,[145] employment[146] and numerous other areas of society and the economy. All of these in turn influence the finances of Americans of color and their access to credit.

To take homeownership as an example, numerous studies demonstrate that systemic racism has affected and continues to affect homeownership rates in markets across the United States.[147] These disparities lead to and compound disparities in wealth, which in turn affect minority business owners’ and entrepreneurs’ ability to access credit and capital.[148] It is regrettably no surprise that the most recent HMDA data, from 2020, continued to demonstrate wide disparities between Whites and people of color in lending for housing.[149]

With respect to small business lending, Black and Hispanic Americans continue to rely more heavily on personal and family savings as a source of financing than White Americans, despite having only a fraction of the wealth of White Americans.[150] Black-owned businesses are turned down for loans twice as frequently as White-owned firms.[151] Recent studies indicate that small businesses in communities of color were not able to access federal COVID-19 relief on par with access by businesses in White areas, including due to possible discrimination.[152]

In short, historical discrimination entrenched inequalities in access to credit and in financial markets. As noted above, Appendix A provides NCRC publications that help to document this fact, supplementing the references in this paper. These inequalities have not been fully addressed and eliminated. The lingering and substantial effects, compounded in some cases by current instances of discrimination, prevent people of color from accessing credit fully and fairly. This provides the required strong basis in evidence to conclude that the government can, and should, adopt race-conscious remedies, including by amending CRA regulations to take race into account in a much more central way than it currently does.

C. Regulators Should Conduct Further Research to Supplement this Evidence, Just as the US Department of Justice Did in Support of Race-Conscious Contracting Programs

The evidence described above of the government’s compelling interest in addressing credit discrimination is strong, but a comprehensive analysis by regulators would make it even more so. This would increase the likelihood that race-conscious CRA components, if subjected to strict scrutiny, will pass muster.

Our proposal that regulators undertake this project is rooted in work the US Department of Justice (DOJ) did to support racial preferences in government procurement in response to the Supreme Court’s 1995 decision in Adarand. Adarand made clear that strict scrutiny applies to government affirmative action programs,[153] creating uncertainty about the constitutionality of existing programs. DOJ surveyed the field to shore up evidence that the preference program was based on a compelling interest as Adarand required.

This effort resulted in a 1996 report summarizing:

the long legislative record that underpins the acts of Congress that authorize affirmative action measures in procurement . . .

Congressional hearings and reports that bear on the problems that discrimination poses for minority opportunity in our society, but that are not strictly related to specific legislation authorizing affirmative action in government procurement;

[] recent studies from around the country that document the effects of racial discrimination on the procurement opportunities of minority-owned businesses at the state and local level; and

[] works by social scientists, economists, and other academic researchers on the manner in which the various forms of discrimination act together to restrict business opportunities for members of racial and ethnic minority groups.[154]

DOJ’s report has played an important role in judicial decisions holding that race-conscious procurement programs are properly supported by a compelling interest.[155] The government has also updated and expanded the supporting evidentiary record in the years since in connection with various constitutional challenges.[156]

Regulators should conduct a similar analysis focused on inferior access to credit stemming from discrimination. This would significantly aid in the defense of race-conscious CRA elements that we expect would be subject to strict scrutiny, which we describe in the following section.