Key Takeaways:

- Black America was in an economic crisis before COVID.

- Growth of Black entrepreneurship has not corresponded with economic growth.

- To produce more personal and community wealth from Black entrepreneurship, public and private sector spending should be intentionally channeled to Black-owned businesses.

Overview

Much like the impact on individuals, the severity with which COVID-19 continues to ravage Black businesses has everything to do with their precondition. To focus primarily on the negative impact of COVID-19 on Black businesses fails to recognize the poor economic health of Black entrepreneurs and small businesses before the COVID crisis and the pre-existing conditions which set the context for recent trends. Despite strong entrepreneurial traditions within Black America, which date back to the very beginnings of the United States, the pre-COVID state of Black business, indeed of Black economics generally, was itself in need of redress. A well-documented history of imposed inequality and denial of wealth-creating opportunity had already left Black America in a pre-COVID economic crisis and a business community largely excluded from avenues of development or expansion.

Key Findings:

Increasing Black entrepreneurship has not corresponded with economic growth:

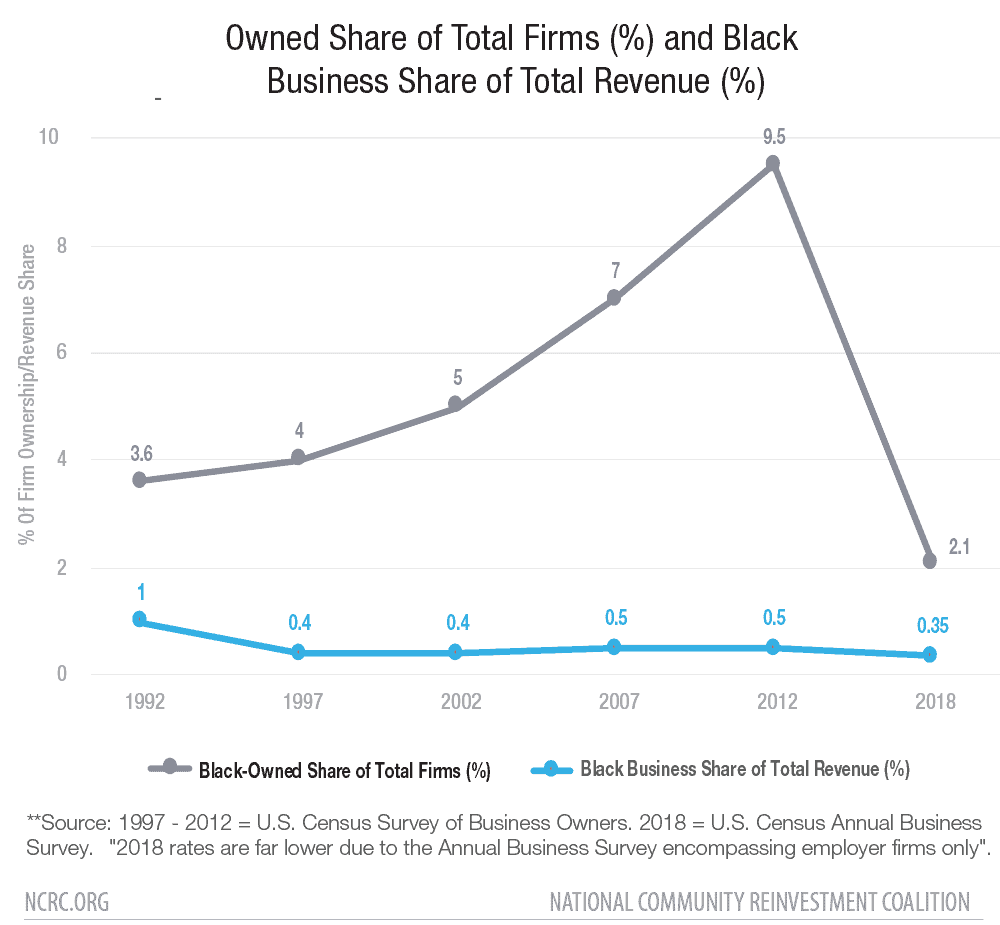

Black entrepreneurship greatly increased between 1992 and 2012, from 3.6% of all firms to almost 10%. Yet even with Black entrepreneurship increasing almost threefold, the proportion of Black revenue decreased from 1% to 0.5%.[1] Also during this time period, Black median income did not increase with Black entrepreneurship. In fact, median Black household income only increased by just over $3,500, after sharply declining in 2000 and 2007.[2] As income climbs in recent years, revenue has continued to decline.

Black Businesses are segregated by geography, industry and asset poverty similar to the African American community as a whole

African Americans comprise 9.5% of business owners,[3] and only 2.1% of firms with employees,[4] yet make up 13% of the U.S. population.[5] Black businesses are largely isolated by geography, primarily in the South where incomes are generally lower; and by industry, in areas of the economy where wages, revenue and start-up costs are also lower such as beauty, hair care, social and health services. African Americans are also concentrated in areas with high rates of COVID-19 infection and resultant slowed economic activity.

Black Businesses are hobbled by racial economic inequality and lack of investment

The racial disparities in entrepreneurship mirror overall racial economic inequality in the United States. Black income and wealth disparities, coupled with low revenue generation among Black businesses, low rates of pay and the challenges of Black firms to attract capital infusion from financial institutions, all highlight the limited return of Black business ownership in terms of income and wealth.

Pre-existing conditions limited Black businesses’ ability to receive COVID-19 relief and hinder a quick recovery

Black businesses have been more susceptible to higher risk of losses due to COVID-19, and have also seen little relief from federal government assistance plans due to their precarious position pre COVID-19. Forty percent of revenue for Black-owned businesses comes from sectors mostly impacted by COVID-19 business closures, which represent a large share of Black firm revenue.[6]

Key Solutions:

- Focus direct stimulus payments in areas where Black business and Black revenue is concentrated. Black consumers, typically the primary customers of Black businesses, are particularly lacking supplemental funds in this time due to business closures, consequential job loss and decimated incomes. Providing supplemental stimulus money to predominantly Black communities and their Black businesses could spur more economic activity.

- Financial institutions should target products and services towards the needs of Black businesses. This would include special purpose credit programs, financial counseling, technical assistance and small business microloans. If products, services and loans were better designed to address the conditions of Black entrepreneurs,[7] then funding would be more accessible than it is now, and Black businesses would find themselves more financially viable and sustainable.

- Use Black Banks and financial institutions to target Black entrepreneurship for Investment. Black banks are better connected to and understand the financial needs, capabilities and situations of Black communities. Fifty-nine percent of Black banks have branches in Black communities, and 67% of loans made by Black banks are made to Black borrowers. Increasing the amount of banks capable of reaching more Black Americans could make capital more accessible to Black entrepreneurs.

- Federal procurement programs need to be more targeted and more strongly implemented toward Black businesses. Federal government procurement contracts or supplier diversity programs that substantively invest in Black-owned businesses have the ability to spur business growth, financially support Black-owned businesses and infuse capital across the nation.

- Stronger corporate transparency should be implemented. In addition to publicly sharing EEOC data, corporate procurement data as it relates to racial and ethnic diversity and gender for both tier 1 and tier 2 suppliers should be collected and shared publicly.

- Increase private investment in Black entrepreneurs. Private entities, such as corporations, foundations or independent business owners, could invest more in Black entrepreneurs and support them in more ways, including mentorship programs with pathways to partnerships or investment. Private entities such as corporations and private foundations should also develop Black entrepreneurship grants to support business owners at every stage in the business life cycle.

Black Entrepreneurship and Wealth

A dominant narrative in America is that entrepreneurial efforts are a surefire shot to wealth-building. This narrative tends to exaggerate the reality of available support and viability of business ownership for African Americans. Societal conceptions of entrepreneurship, an aspiration for many, regardless of race or class, simultaneously under-report the overall state of precarity for African American entrepreneurship and the African American economic condition as a whole. A broad look at the state of Black-owned businesses shows that while Black Americans continue to increase their attempts to develop their businesses, their ability to increase their share of revenue generated has remained mostly stagnant. Since 1992, Black people have added nearly 2 million new businesses (1,963,491), growing their business ownership share from 3.6% in 1992 to almost 10% in 2012.[8] Yet, Black businesses only increased their share of total U.S. business revenue by 0.3%. The 2018 U.S. Census Annual Business survey, which only surveys employer firms,[9] found that Black-owned employer firms comprised 2.1% of total businesses, and generated a mere 0.3% of total business revenue.[10]Despite the strong entrepreneurial tradition in the Black community, the inability to generate higher material income illustrates the stunted growth in wealth and economic opportunities caused by racial economic inequality.

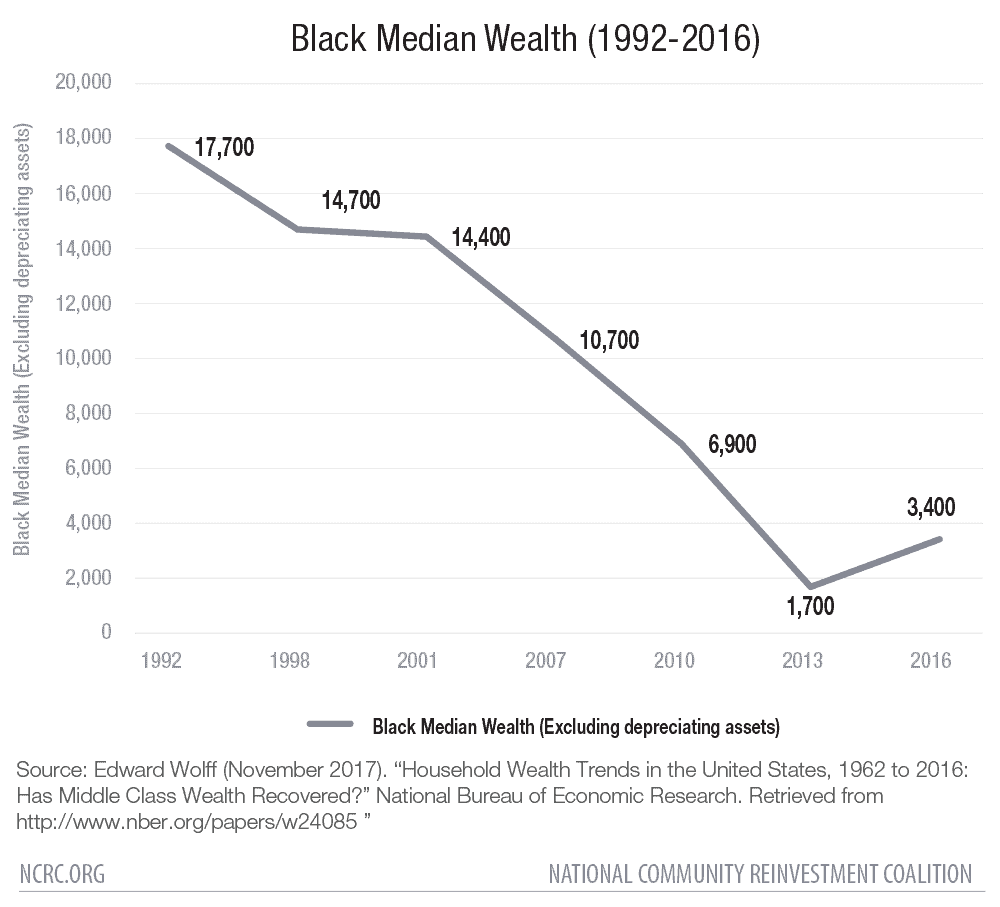

A strong increase in Black entrepreneurship can be seen with a fourfold increase in the number of Black firms in 15 years. Yet, this substantial increase in Black entrepreneurship has not come with a commensurate increase in revenue (0.9% to 1.3%). From 1992 to 2012, Black firm revenue increased from $30 billion to $150 billion; however, this increase barely kept up with the overall increase in other firms’ business revenue. Similarly, this increase in firm revenue has not increased Black wealth levels. In 1992, Black median wealth was $17,700; by 2013 (the closest year to 2012 SBO survey), Black median wealth had actually dropped to $1,700.[11]

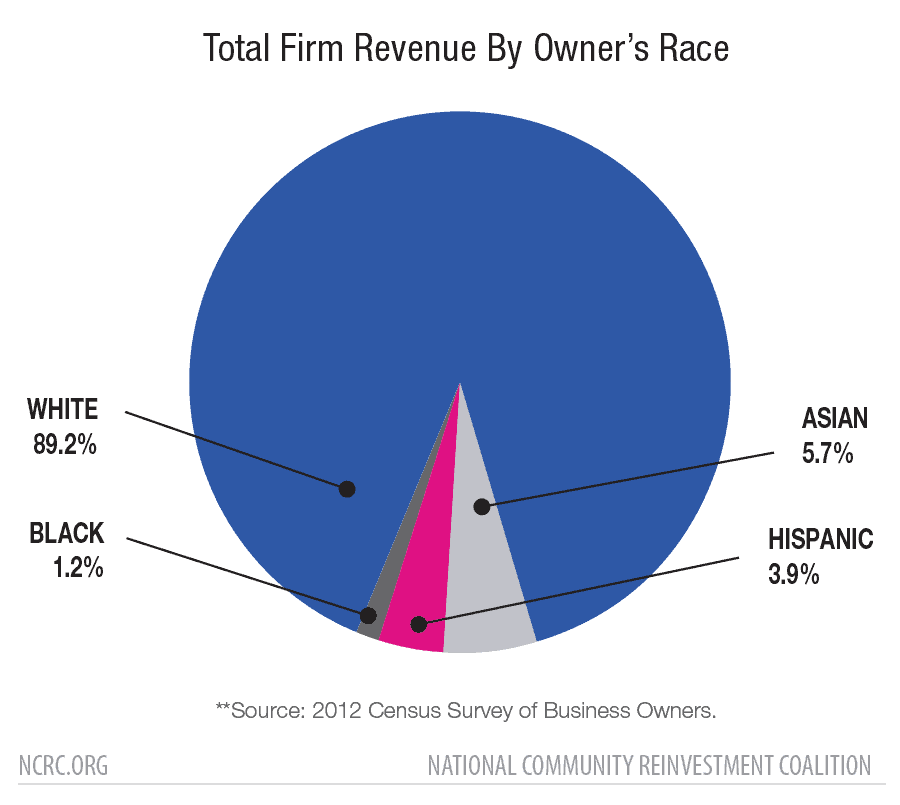

The 2012 Census Survey of Small Business Owners, the most recent survey of both employer and nonemployer business owners, found there to be 2.58 million Black-owned businesses in the United States, generating $150 billion in annual revenue and supporting 3.56 million U.S. jobs.[12] While depicted as impressive in some media or journalism circles, the reality is that these businesses and revenue they generate represented only 0.5% of total U.S. firm sales, and the millions of firms and jobs represented only 9.5% of total U.S. firm ownership.[13] Understood within this broader context alone, the economic fragility of African American entrepreneurship pre-COVID is much more apparent.

CAPTION: By comparison, White-owned firms accounted for 88% of U.S. firm sales, and 70.9% of all U.S. businesses.[14] Black-owned firms’ annual revenue of $150 billion paled in comparison to White-owned firms’ staggering $11 trillion in annual revenue. Similarly, Asian-owned firms generated approximately $700 billion in annual revenue, and Hispanic owned firms generated nearly $473 billion in revenue.[15]

While Black people comprise 13% of the overall U.S. population, Black-owned businesses represent 9.5% of all American firms. Only 2% of firms with employees are Black owned firms.[16] Within that small group of Black-owned employer firms, 2012 data showed Black firms owned by Black men paid an average salary of $32,061 and Black, women-owned businesses paid an average of $24,303,[17] far less than the national average of $44,321.[18] The lack of capital available to Black business owners and Black communities at large, in which many Black-owned businesses are located, in turn affects the economic opportunity of its workers. Furthermore, Black nonemployer firms are much more likely to operate at a loss than at a profit.[19] These numbers are in stark contrast to those of White Americans who currently enjoy ownership of 78% of all private businesses, despite White Americans comprising only 62.8% of the entire population. Eighty-two percent of all employer firms in the United States are White-owned.[20]

The kinds of businesses owned by Black people must also be considered, as the industry distribution is one key illustration of the wealth gap faced by Black entrepreneurs. Industries such as primary care and mental health services, plumbing, heating/AC contractors; law practices; and full-service restaurants not only garner higher revenue, but are also less likely to be owned by Black Americans. Black-owned firms, on the contrary, are concentrated in industries with lower revenue such as beauty salons, childcare services, home health care services, janitorial services and barbershops. White firms in the same industries bring home higher revenue than their Black-owned counterparts, driving a larger wedge within the racial wealth gap.[21]

The Impact of Racial Economic Inequality on Entrepreneurship

The racial disparities in entrepreneurship mirror overall racial economic inequality in the United States. African Americans exist in a state of economic insecurity compared to the general population and other racial groups. While the Black median income is around $41,361, the national median income is around $62,000, and the White median income is upwards of $71,000. The median White family has 41 times more wealth than the median Black family. Prior to COVID-19, Black unemployment was at its lowest rate in years, yet there was still substantive racial inequality in unemployment. Black unemployment was 6.5%, while the national unemployment rate was 3.9%. The White unemployment rate before COVID-19 was 3.5%.[22] As of January 2021, Black unemployment was at 9.1% compared to a White unemployment rate of 5.7%.[23]

This economic reality shines light on the disparate economic position from which African Americans began the pandemic and how it directly impacts their entrepreneurial successes and difficulties. Cycling for generations, low starting wealth affects access to credit, which both affect ability to obtain certain credentials and licenses, or ability to enter fields that require large starting investments in industries that often have greater economic returns. This relegates Black entrepreneurs to low-revenue industries, which as a result, are less lucrative, and are not a viable pathway to closing the racial wealth divide.

Disparities in Business Credit and Investment

Along with income and wealth inequality, African American entrepreneurs face great challenges in attaining affordable credit and investment. The historic credit gap was exacerbated more recently during the 2008 Great Recession where federal deposits, defended at the time as necessary to keep banks lending, have still not been redistributed as loans, primarily to small businesses. The decline in overall SBA loans to Black businesses between 2008 and 2016 from 8% to 3% is very concerning.[24] Besides disparities in service from financial institutions, racial disparities within banking relationships and credit scores impact entrepreneurs’ ability to procure financing. Data shows that 56% of White-owned firms used a loan or line of credit to fund business operations, compared to 44% of Black-owned firms.[25] Thirty-nine percent of nonemployer firms with revenue over $100,000 used loans or lines of credit regularly, while only 24% of nonemployer firms with revenue under $100,000 reported using loans. The fact that only 4% of Black firms have employees and the lack of finance designed for low-income, non-employer firms is a fundamental obstacle for most Black businesses.[26]

For Black entrepreneurs, the cyclical nature of wealth and credit gaps make economic survival more difficult and places more responsibility on the individual business owner. Black entrepreneurs were more likely to use their own personal credit score to obtain business funding, even though Black-owned firms reported having personal credit scores below 720 in larger shares. Larger shares of White and Asian firm owners reported scores of over 720, yet relied on personal credit scores in smaller shares compared to Black and Hispanic firm owners[27] Black-owned firms were more likely than White-owned firms to use personal funds to fund business operations — 28% of Black-owned firms did so, while 16% of White-owned firms used personal funds.[28] White-owned firms were more likely than Black-owned firms to use retained business earnings – profits or the shareholder’s equity in a company after dividends are distributed – as a primary funding source instead of personal funds — 70% to 62%, respectively. White-owned firms, which receive greater revenue, are in turn more capable of funding their businesses with retained earnings and avoid draining their own personal funds. This is not the same for Black firms, which produce less revenue and therefore must rely on their own personal funds despite on average greater personal economic instability. When accounting for the racial wealth divide, the firms which use their own personal funds are drawing from lower wealth levels than their White counterparts. The unequal reliance on personal funds recreates wealth disparities, as minority firm owners drain their personal wealth while White owners expand theirs, as they are more financially capable to save their own personal funds and use their greater revenues to fund their businesses.

Yet, the lack of wealth experienced by Black entrepreneurs and the consequential financial barriers still do not result in any fewer attempts by Black Americans to attain requisite funding. Fewer than one in four Black employer firms have a recent borrowing relationship with banks, and one in 10 Black nonemployer firms were found to have banking relationships compared to one in four White-owned non-employer firms. Recent survey evidence finds that both employer and nonemployer Black-owned firms are applying for financing at equal or higher rates than White-owned firms, yet are denied at higher rates.[29]

The Geographic Isolation of Black Entrepreneurship

The industries Black entrepreneurs operate in are limited as is their location geographically. African American businesses rarely can be considered “national” in that they are concentrated in a handful of majority-minority locations, and tied economically to an almost exclusively Black clientele. Black business activity is found to be correlated with Black population density, which tends to be in high-density metropolitan hubs and cities. Black populations are continuously growing in metropolitan hubs. Forty percent of receipts from Black-owned businesses are concentrated in just 30 counties, roughly 1% of all counties in the country.[30] However, as will be discussed, that correlation between Black population density and Black firm ownership does not correspond to the location of Black affluence, income or wealth.

The correlation of Black-owned firms located in areas with a high density Black population may play a role in revenue discrepancies. The impact of the geographic isolation of Black business is magnified by the particular conditions of those relatively few counties. The asset poverty of high-density Black counties affect potential revenue, since customers of Black-owned firms are coming from low- and moderate-income (LMI) communities, with low wealth levels. There are few high-income areas with a high concentration Black population as well. Furthermore, even in predominantly Black areas with higher incomes than average, the median wealth is still relatively low compared to other racial groups and population areas. Considering that many businesses maintained by African Americans are in the southern part of the United States, where income is lower and poverty is higher — and in particular for Black workers targeted by these businesses — it weakens the potential for these businesses to grow, thrive or even survive.

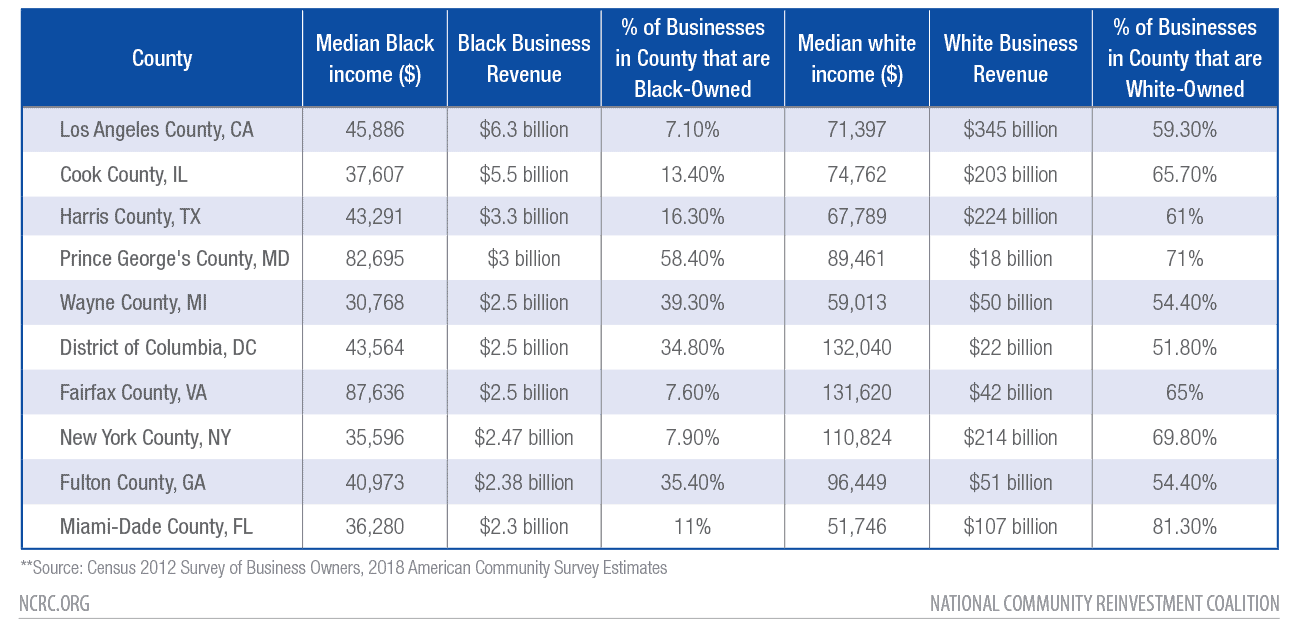

In the top 10 counties where Black business revenue is concentrated, the disparities in income across racial lines can be seen. It is important to evaluate the income levels of Black business clientele. For example, in Cook County, home to the second highest concentration of Black business revenue and where 20% of businesses are Black-owned, the median Black income is 49% less than the median White income. As seen with income disparities within the counties most lucrative for Black businesses, there is little relationship between Black business revenue and racial income equity in an area.

Speculative Look on COVID-19’s Impact on Black Entrepreneurs

The ultimate impact of COVID-19 on African American businesses, let alone all businesses, will not be fully known for some time. Millions remain unemployed or underemployed, and it remains unclear to what extent these job losses will be recovered as the nation attempts to recover not only economically but public health-wise. Some businesses shut down during the pandemic will be lost forever. Others will reconfigure their infrastructure, method of operation and employment as a means of survival. It is likely that the businesses capable of reconfiguring infrastructure, operations and employment will be the ones with pre-existing higher revenue and larger employee bases — the types of firms that are rarely Black-owned.

Due to preexisting factors, Black-owned firms are much more likely to be in an economically precarious position than White firms, which leads to much longer-term negative economic impacts for African Americans. While 73% of White employers operated at a profit, had high credit scores and used retained business earnings to fund operations, only 42% of Black employer firms met that criteria.[31] Furthermore, NCRC recently found that Black business owners, who had business credit products, were more likely than White business owners to have outstanding balances.[32]

As the United States approaches almost a year of widespread economic, sociopolitical and public health suffering, the differences in experience and disparate impacts can now be evaluated with more information and greater clarity. Reimagine Main Street’s survey,[33] conducted between September and November of 2020, found that among surveyed Black business owners, 85% reported negative effects, with 50% reporting very negative impacts. Thirty-three percent of Black respondents reported having less than one month’s worth of cash on hand. A staggering 76% of Black respondents expected a need for financial assistance or additional capital over the next six months.

Forty-six percent of the survey’s Black respondents reported a 2019 revenue of less than $100,000. Thirty-one percent reported a 2019 annual revenue of $100,000 – $500,000. This fact is particularly worrisome, considering the survey’s finding that 40% of Black business owners reported their 2020 revenues were down 25% – 75% from 2019 revenues. Fifteen percent of Black business owners reported revenues down by at least 76%. These are stark and impactful losses in income and wealth generating opportunities for Black business owners, who are starting with small revenue sizes, yet are experiencing severe losses in the wake of COVID-19.

The aforementioned concentration of African American businesses geographically is already said to have played a negative role in how those firms have or have not survived through the COVID-19 pandemic. When examining the top 30 counties where Black business activity is concentrated, 19 were areas with the highest numbers of COVID-19 cases at the beginning of the pandemic. Recovery, both in terms of Black Americans recovering directly from COVID infections and Black businesses recovering from COVID-related economic crises, have run parallel in their insufficiency. With communities and consumers of Black businesses being greatly impacted by COVID-19, their financial capability to spend money with local businesses has been similarly impacted. Whether from job loss or suffering health, Black businesses’ usual customers cannot support local firms at the same level they did before COVID.

How Pre-existing Conditions Prevented Black Businesses from Obtaining COVID-19 Relief

Black businesses, which are less lucrative and more susceptible to higher risk of losses due to COVID-19, have also seen little relief from federal government assistance plans. The Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) established initially after the crisis by the Small Business Administration (SBA), and which was said to be the government’s primary lifeline for many businesses, has “… left significant coverage gaps: these loans reached only 20% of eligible firms in states with the highest densities of Black-owned firms, and in counties with the densest Black-owned business activity, coverage rates were typically lower than 20%.”[34] Assessments of widespread lending gaps between Black and White firms suggests the pre-existing precarity of Black firms, including their low credit ratings, played a major role. There is evidence also suggesting that Black firms, having entered the crisis in a pre-established weakened position, may have been reluctant to apply for PPP relief due to uncertainty about future business activity and uncertainty of economic survival.

Studies of PPP lending patterns illustrate that much of the dispersed aid did not correspond to areas of greatest need. In fact, because the PPP loan was set up to be managed or mediated by banks, the aforementioned issues of prior relationships has been cited as a reason for Black businesses receiving not enough or not enough in time. Black entrepreneurs were more likely to turn to fintech lenders due to the perceived higher chance of successfully receiving financing from these platforms instead of traditional lending institutions. Fintech lenders, however, were not authorized to disperse PPP funds during its initial phases.[35] Twenty-nine percent of Reimagine Main Street’s[36] Black survey respondents reported successfully receiving the PPP loans applied for — the lowest rate of success among surveyed demographics. Of the Black respondents who did not apply for federal assistance, 65% cited their reason as assuming their business was ineligible for assistance.

The unequal difficulty in securing relief funds can be partly attributed to the banking relationships of Black-owned firms. As previously mentioned, fewer than one in four Black-owned employer firms, and one in 10 Black nonemployer firms had a recent borrowing relationship with a bank, compared with one in four White-owned nonemployers, even though Black entrepreneurs applied for financing at equal or higher rates than White-owned firms. Furthermore, only 2% – 4% of Black-owned firms had employees, meaning more Black-owned businesses likely lacked prior banking relationships since most were nonemployer firms. Employer firms often have higher revenues and greater financial needs, which by nature requires continuous banking relationships which over time may build greater trust. The unequal and disparate access to capital faced by Black entrepreneurs has exacerbated COVID-19’s economic impacts, and widened pre-existing disparities.

As previously noted, White-owned businesses are more likely to be older, more established firms with more employees and revenue. The needs of a larger employer firm naturally requires a larger accounting and legal department, which in turn, results in companies more able to take advantage of programs like PPP that require navigating relationships with financial institutions. With Black business owners often being the sole workforce of their firm, it is more difficult to navigate relief aid while also juggling business management and personal matters.

Seventy percent of all Reimagine Main Street’s respondents indicated they would like a second round of PPP loans. Almost 90% of Black respondents reported grants would be most beneficial to their business. Black respondents were also the most likely to report that increased support from community organizations would be beneficial to their business — over 40% of Black respondents said so, compared to 30% of all other business owners. The greater rate of Black business owners reporting a preference for relief in the form of grants illustrates that Black businesses are in need of direct capital. The PPP loan structure, with a complicated and arguably inaccessible application and forgiveness process, did not suit the needs of Black businesses, as Black business owners lack the organizational infrastructure such as an accounting department — let alone very many employees — to assist in the loan application and forgiveness process. Direct capital infusion, such as in the form of grants, is the most relevant form of funding for Black business owners due to their business structures and capacity. Furthermore, the preference for support from community organizations suggests that Black businesses are in need of resources provided by these organizations, such as technical assistance for grant and/or loan applications.

NCRC recently conducted preliminary analysis of the SBA’s PPP loan data. That analysis found that low-income neighborhoods received less than a quarter as many PPP loans as upper-income tracts. The actual loan amount was also significantly less among low-income neighborhoods compared to upper-income neighborhoods; $36,481 compared to $100,539, respectively. Neighborhoods with a higher concentration of people of color also received significantly fewer loans, at lower amounts.[37]

During the second draw of PPP funds, which opened for applications on January 13, 2021, the SBA attempted to remedy disparities in lending patterns and in access that was experienced during the first round. To do this, SBA set aside $25 billion of PPP funds specifically for either borrowers with a maximum of 10 employees, or for loans of $250,000 or less to eligible borrowers in LMI neighborhoods. Additionally, the SBA initially only accepted second draw PPP loan applications from community financial institutions. During the third and most recent draw of PPP funds, which opened on February 22, 2021, the SBA set a 14-day exclusivity period for small businesses and nonprofits with fewer than 20 employees as well as sole proprietors. The effectiveness of these steps remains to be seen, as they may have come too late for many businesses that were severely impacted by the pandemic to the point of permanent closure.

Industry Concentration of Black Businesses & Disproportionate COVID Closures

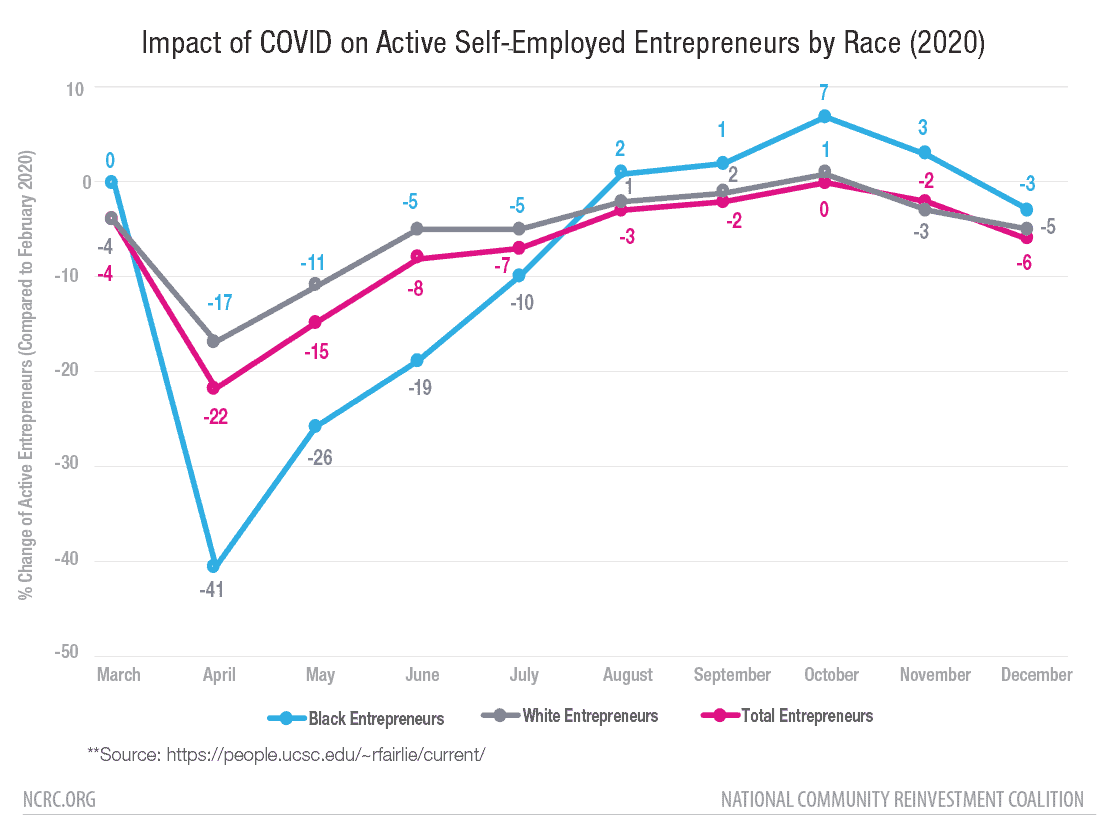

Early indications showed that COVID-19 had a tremendous effect on African American businesses, which before the pandemic were in a much more precarious position. During the height of public health-mandated business closures, from February to April 2020, active African American business owners dropped from 1.1 million to 640,000. As businesses began reopening over the summer, the Black businesses that survived the early months of COVID began to bounce back. Economic stabilization for business owners seemed to be reached by the fall, but with COVID-19 cases skyrocketing to unprecedented levels in the winter, forcing some states to shut businesses back down, active business rates began to decline again.[38]

Forty percent of revenue for Black-owned businesses comes from just five sectors: leisure and hospitality, retail trade, transportation and utilities, construction and “other services” such as drycleaning and laundry, personal care, pet care or photofinishing services.[39] These five sectors, which have been the most impacted by COVID-19 business closures, represent a large share of Black firm revenue.[40] This disproportionate impact of COVID-19 closures on profitable sectors for Black firms likely has and will worsen the economic standing of Black-owned businesses. The first wave of COVID significantly wiped out many African American businesses, particularly the most economically insecure. The fall 2020 COVID wave and economic challenges that continued into 2021 threaten the greatest revenue generating industries for Black entrepreneurs.

On the other hand, the industries in which White entrepreneurs are most concentrated are not only more lucrative, but are also weathering COVID-19’s economic recession better than other industries. White-owned firms earn high revenue in industries such as offices of physicians, plumbing, offices of lawyers and full-service restaurants. For example, among offices of physicians, 48% of total sector revenue came from White-owned firms. From March to August 2020, health related businesses experienced less than three closures out of every thousand businesses.[41] In comparison, beauty salons, which are 16% Black-owned,[42] are among an industry that has been especially hard hit during COVID-19. From March 1 to the beginning of September 2020, 16,585 beauty businesses closed — 42% of them permanently.[43] Considering the high concentration of Black ownership in industries such as beauty, the economic impacts of business closures will likely disproportionately harm Black entrepreneurs.

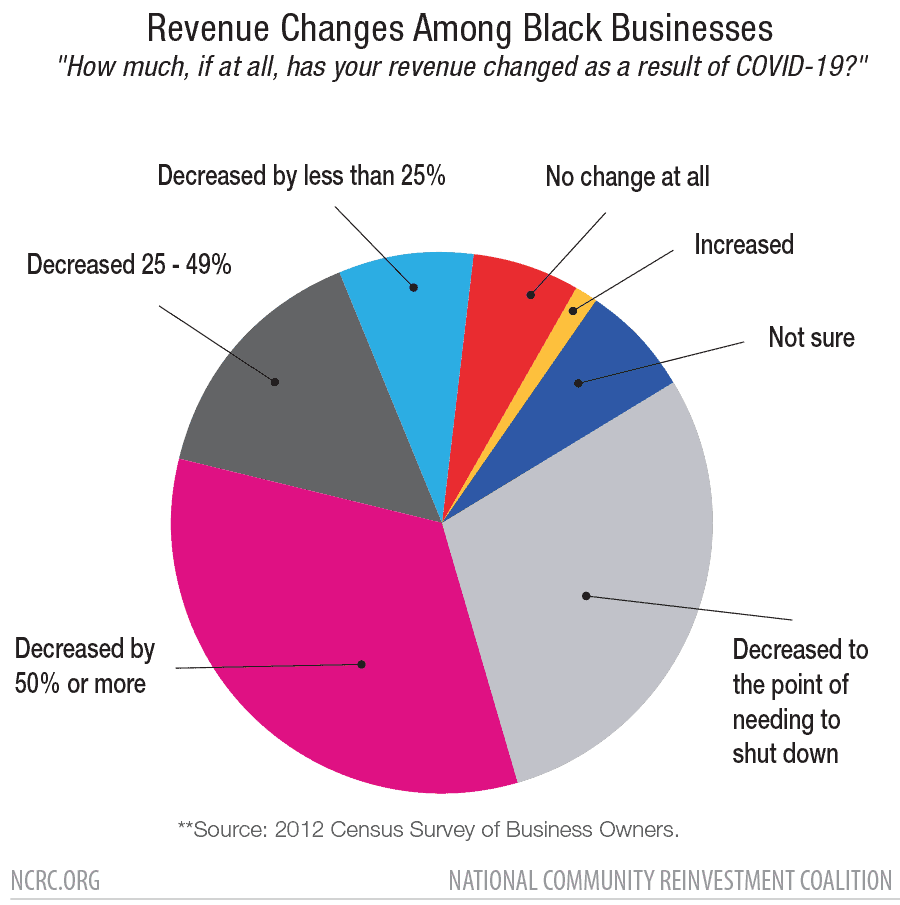

An October 2020 survey conducted by the Association for Enterprise Opportunity fielded the experiences of over 900 small businesses from across the nation, across all sectors and race/ethnicities. The survey skewed towards more established firms, and therefore did not fully capture the experiences of recently established and nonemployer businesses. The survey revealed COVID’s effect on revenue and the disproportionate industry closures of Black businesses, largely due to the precarious financial conditions and inequality pre-COVID as aforementioned.

CAPTION: “AEO’s survey findings about COVID’s effects on revenue illustrate the disproportionate effects of industry closures on Black businesses. 33% of Black respondents reported revenues decreased by 50% or more as a result of COVID-19, while 29% reported that revenues decreased significantly to the point of needing to shut down. Similarly, 20.7% of Black-owned businesses reported that customer retention rates decreased by 50% or more; 22% reported customer retention had decreased to the point of needing to shut down.”

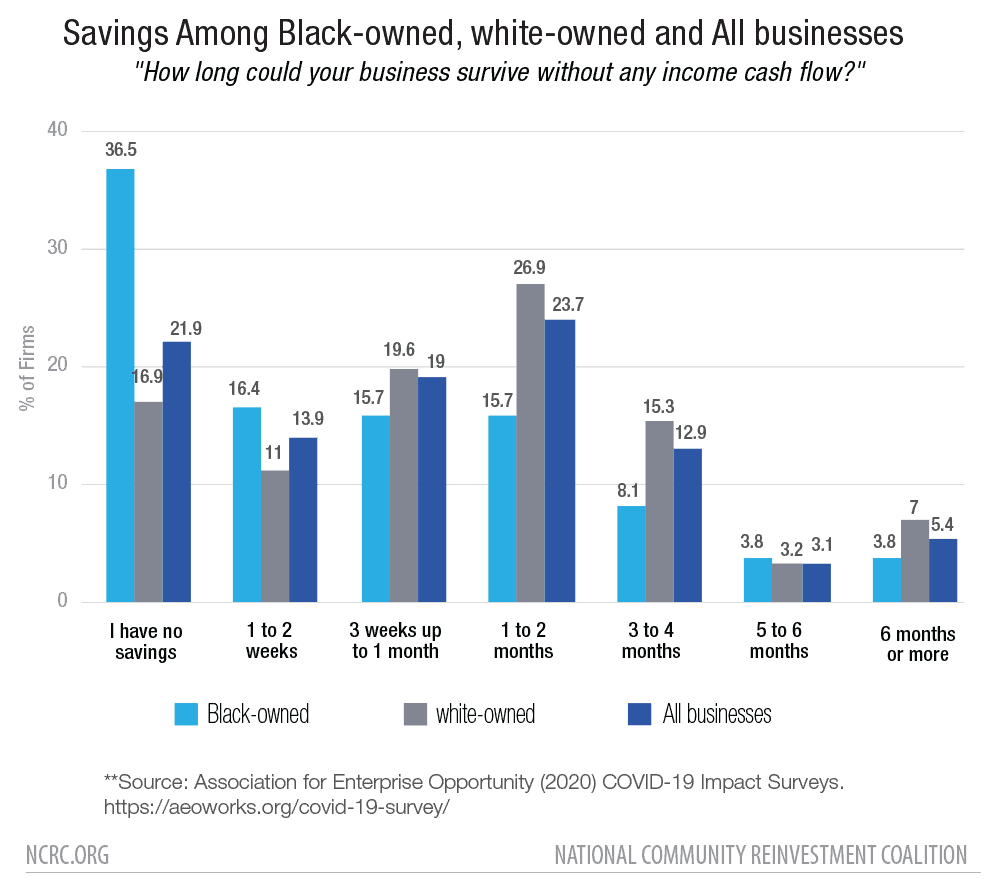

CAPTION: “The AEO survey finds that Black businesses have less savings, and therefore less capability for the businesses to survive without any income cash flow. Shockingly, 36.5% of surveyed Black businesses have no savings. Considering the disproportionate impact of COVID closures on Black businesses, the large number of Black businesses who have little to no savings means they are less likely to be able to survive COVID closures. White-owned businesses reported having more savings, possibly a virtue of being in business for longer. Fifty-two percent of those surveyed have been in business for 10 years or more. In comparison, 32.7% of surveyed Black businesses had been in business for 10 years or more. Being in business longer means greater opportunity for savings generated, and more ability for a business to weather economic crises such as business closures.”

CAPTION: “The AEO survey finds that Black businesses have less savings, and therefore less capability for the businesses to survive without any income cash flow. Shockingly, 36.5% of surveyed Black businesses have no savings. Considering the disproportionate impact of COVID closures on Black businesses, the large number of Black businesses who have little to no savings means they are less likely to be able to survive COVID closures. White-owned businesses reported having more savings, possibly a virtue of being in business for longer. Fifty-two percent of those surveyed have been in business for 10 years or more. In comparison, 32.7% of surveyed Black businesses had been in business for 10 years or more. Being in business longer means greater opportunity for savings generated, and more ability for a business to weather economic crises such as business closures.”

Addressing Disparities in Black Entrepreneurship

What the COVID-19 crisis continues to demonstrate is a need for a robust public / private partnership that can stimulate business and consumption. The sectors of the economy most in recovery (or expansion), namely manufacturing, technology and finance, have high rates of concentrated White ownership and are less likely to be Black-owned. Similarly, most Black firms are small, employ few, pay those few less than the national average, and depend on a Black customer base that is more economically insecure than others both pre-COVID and during the COVID crisis.

The pre-existing condition of Black entrepreneurship finds roots in the deep asset poverty that hobbles Black entrepreneurs and Black communities as a whole. Initiatives that seek to strengthen Black entrepreneurship can strengthen the overall state of Black wealth. Similarly, initiatives and interventions designed to address Black asset poverty and the racial wealth divide will improve the landscape of Black entrepreneurship. Comprehensive asset infusion into the Black community is needed, as are targeted asset investments specifically for Black entrepreneurs.

Suggestions for policy consideration and future elaboration include:

A. Provide tax relief to Black businesses to increase cash-on-hand and direct stimulus payments in areas where Black business and Black revenue is concentrated to spur consumption with Black businesses. Even prior to the current COVID-inspired economic crisis, it had been feared that continued racial wealth and income inequality would create a lag on the entire economy, thought then to be anywhere from “4-6%” of GDP. In fact, the racial wealth divide was already said to have a:

… dampening effect on consumption and investment [which] will cost the US economy between $1 trillion and $1.5 trillion between 2019 and 2028 — 4 to 6 percent of the projected GDP in 2028….[44]

Consumption, still at roughly 67% of GDP, remains a driving force of the U.S. economy. As described previously, Black consumers are disproportionately lower income and in wealth poverty and are the primary supporters and investors in Black businesses. One of the greatest ways to stimulate Black entrepreneurship – and ultimately the broader economy – is ensure businesses have enough cash flow to meet additional expenses brought on by COVID-19 to maintain operations and stimulate Black consumers in highly concentrated Black areas to support these businesses.

B. Financial institutions need to develop credit products, financial counseling, technical assistance and small dollar loans/grants that address the economic reality of Black businesses and the Black community as a whole. Mainstream small business loans and credit products do not account for historic economic disenfranchisement that has resulted in African Americans’ lower income and wealth levels. Products, services and loans/grants should be better designed to address the conditions of Black entrepreneurs and the reality of income and wealth inequality to better serve Black entrepreneurs.

C. Use Black Banks and financial institutions to target Black entrepreneurship for Investment: 59% of Black banks have branches in Black communities, and 67% of loans made by Black banks are to Black borrowers.[45] Black banks are better situated to increase banking and access to capital among Black communities. Strengthening Black institutions is also fundamental to bridging the racial wealth divide.

D. Implement a small business data transparency rule mandated under Section 1071 of the Dodd-Frank Act. Proposed rules would establish uniform, transparent data collection practices and provide much-needed information about applications and lending to small businesses, woman-owned businesses and businesses owned by people of color. Information gathered from data would provide insight on loan pricing, number of employees, and years in business; this information can be used to ensure fair and equitable access to financing. The proposed rules would also implement disclosure requirements among small business lending institutions to prevent banks, credit unions, online lenders and others from exploiting loopholes. Such data transparency would be particularly useful to ensure racial equity amongst business owners, as it would allow for analysis of racial disparities in lending patterns.

E. Procurement Federal, State and Local: Currently the U.S. government spends about $500 billion annually on goods and services.[46] Thirteen percent (the African American population share) of $500 billion is $65 billion, which is more than half of the revenue of 2018 Black businesses. Similarly state and local businesses spend billions of dollars in procurement and could make a significant impact in strengthening Black entrepreneurship. Procurement contracts and supplier diversity programs with Black-owned businesses have the potential to spur business growth, financially support Black-owned businesses and infuse capital across the nation.

F. Corporate: Corporate America has made too little progress in employing African Americans at all levels of business, and in procurement with Black-owned businesses. All private corporations that file EEOC data should publicly share this data as an act of transparency; they should also share their procurement data by major racial and ethnic categories. Both tier 1 and tier 2 supplier data should be collected and published. Inclusive change targeting African Americans can have a positive effect on the economic condition of African Americans as a whole and Black entrepreneurship as a whole.

G. Make permanent unemployment benefits for the self-employed

Entrepreneurship is a series of failures that lead to success. Individuals that come from communities of little income and evel less wealth do not have the private capital to serve as a safety net for the inevitable failures that come with entrepreneurship. During the pandemic, the self-employed were granted access to unemployment benefits. This should be made permanent so that more Americans and African Americans in particular have greater opportunity to participate in entrepreneurship.

H. Universal Healthcare: Wealth creation requires a public policy framework within which other private actors can work more effectively. For example, the current employer-based healthcare model saddles U.S. businesses with $880 billion in costs to cover their employees which creates a lag on their own earnings, worker pay and the incentive for many to develop new firms. One framework policy that could make entrepreneurship a more achievable and equitable pathway for African Americans would be universal healthcare. Universal healthcare could make business ownership more attainable and sustainable for African Americans.

- If there was nation-wide secure, universal and accessible public health care, businesses would not have to devote as many funds toward employer-based health care. This saved money could go towards operational fees, upscaling and/or paying their workers higher ages.

- The elimination of dependency on employer-based health care would make workers less dependent on their jobs and grant more freedom to switch career paths, such as a pivot towards entrepreneurship.[47]

- Universal healthcare would relieve one less stress for young or new entrepreneurs, making business ventures less of a financial risk.

Dedrick Asante-Muhammad, Chief of Race, Wealth and Community, NCRC

Dr. Jared Ball, Professor of Communication Studies, Morgan State University

Jamie Buell, Racial Economic Equity Coordinator, NCRC

Joshua Devine, Director of Racial Economic Equity, NCRC

[1] Census Survey of Business Owners, 1992 – 2012.

[2] Satistia. “ Household Income of Black private households from 1990 to 2019. Retrieved from: https://www.statista.com/statistics/203295/median-income-of-black-households-in-the-us/

[3] U.S. Census Survey of Business Owners 2012.

[4] U.S. Census Annual Business Survey 2018.

[5] U.S. Census Bureau Quick Facts, 2019. Retrieved https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/US/PST045219

[6] McKinsey & Company (April 2020). “COVID-19: Investing in Black Lives and Livelihoods”. P. 15. Retrieved from https://www.mckinsey.com/~/media/mckinsey/industries/public%20sector/our%20insights/covid%2019%20investing%20in%20black%20lives%20and%20livelihoods/covid-19-investing-in-black-lives-and-livelihoods-report.pdf

[7] For more information, see https://ncrc.org/reri/

[8] Census Survey of Business Owners, 1992 – 2012.

[9] Authors have chosen to focus on findings from the U.S. Census Bureau 2012 Survey of Business Owners, since that is the last survey to encompass nonemployer firms, which is the majority (96% – 98%) of Black-owned businesses.

[10] U.S. Census 2018 Annual Business Survey.

[11] Collins, Chuck, Asante-Muhammed, Dedrick, Hoxie, Josh & Terry, Sabrina. (2019). “Dreams Deferred: How Enriching the 1% Widens the Racial Wealth Divide.” Institute for Policy Studies. Retrieved from: https://ips-dc.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/IPS_RWD-Report_FINAL-1.15.19.pdf p.8.

[12] Association for Enterprise Opportunity (February 2017). “The Tapestry of Black Business Ownership in America: Association for Enterprise Opportunity. Retrieved from: https://aeoworks.org/images/uploads/fact_sheets/AEO_Black_Owned_Business_Report_02_16_17_FOR_WEB.pdf

[13]McManus, Michael. (2016). “Minority Business Ownership: Data from the 2012 Survey of Business Owners” U.S. Small Business Administration. Retrieved from: https://cdn.advocacy.sba.gov/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/07141514/Minority-Owned-Businesses-in-the-US.pdf

[14] Association for Enterprise Opportunity (February 2017). “The Tapestry of Black Business Ownership in America: Association for Enterprise Opportunity. Retrieved from: https://aeoworks.org/images/uploads/fact_sheets/AEO_Black_Owned_Business_Report_02_16_17_FOR_WEB.pdf

[15]U.S. Census Survey of Business Owners, 2012

[16] USA Facts (August 2020). “A higher share of Black-owned businesses are women-owned than non-Black businesses.” Retrieved from: https://usafacts.org/articles/black-women-business-month/

[17]Austin, Algernon (April 2016). “The Color of Entrepreneurship.” Center for Global Policy Solutions. Retrived from: http://globalpolicysolutions.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/Color-of-Entrepreneurship-report-final.pdf p. 11

[18] Social Security Administration, 1951-2019 “National Average Wage Index”. Retrieved from: https://www.ssa.gov/oact/cola/AWI.html

[19]Federal Reserve Bank of New York (2019). “Small Business Credit Survey: Report on Nonemployer Firms.” Retrieved from: https://www.fedsmallbusiness.org/medialibrary/fedsmallbusiness/files/2019/sbcs-nonemployer-firms-report-19.pdf

[20] Federal Reserve Banks (2020). “Small Business Credit Survey: Report on Nonemployer Firms.” Retrieved from: https://www.fedsmallbusiness.org/medialibrary/FedSmallBusiness/files/2020/2020-sbcs-employer-firms-report

[21] Association for Enterprise Opportunity (AEO) (2017). “The Tapestry of Black Business Ownership in America: Untapped Opportunities for Success”, p. 11. Retrieved from https://aeoworks.org/images/uploads/fact_sheets/AEO_Black_Owned_Business_Report_02_16_17_FOR_WEB.pdf

[22]Asante-Muhammed, Dedrick and Buell, Jamie (February 2020). “Racial Wealth Snapshot: African Americans and the Racial Wealth Divide.” Retrieved from: https://ncrc.org/racial-wealth-snapshot-african-americans-and-the-racial-wealth-divide/

[23]U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2020. Retrieved from: https://www.bls.gov/news.release/empsit.t02.htm

[24]Lee Amber, Michell, Bruce & Lederer, Anneliese (September 2019). “Disinvestment, Discouragement and Inequity in Small Business Lending.” National Community Reinvestment Coalition. Retrieved from: https://ncrc.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/NCRC-Small-Business-Research-FINAL.pdf

[25] Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta (2019). “ Small Business Credit Survey: Report on Minority Owned Firms. Retrieved from: https://www.fedsmallbusiness.org/medialibrary/fedsmallbusiness/files/2019/20191211-ced-minority-owned-firms-report.pdf p. 5

[26] Association for Enterprise Opportunity (AEO) (2017). “The Tapestry of Black Business Ownership in America: Untapped Opportunities for Success”, p. 11. Retrieved from https://aeoworks.org/images/uploads/fact_sheets/AEO_Black_Owned_Business_Report_02_16_17_FOR_WEB.pdf

[27] Federal Reserve Bank (2019). “Small Business Credit Survey: Report on Minority-Owned Firms”. P. 6. Retrieved from https://www.fedsmallbusiness.org/medialibrary/fedsmallbusiness/files/2019/20191211-ced-minority-owned-firms-report.pdf

[28] Ibid., p. 4 – 5.

[29]Kramer Mills, Claire & Battisto, Jessica (August 2020). “Double Jeopardy: COVID-19’s Concentrated Health and Wealth Effects in Black Communities.” Federal Reserve Bank of New York. Retrieved from: https://www.newyorkfed.org/medialibrary/media/smallbusiness/DoubleJeopardy_COVID19andBlackOwnedBusinesses

[30] Ibid., p. 2

[31]Ibid. p. 5

[32] Lederer, Annelise and Oros, Sara (2021). “Are Loan Modifications For Small Businesses A Possibility in the COVID-19 Pandemic.” National COmmunity Reinvestment Coalition. Retrieved from: https://ncrc.org/are-loan-modifications-for-small-businesses-a-possibility-in-the-covid-19-pandemic/

[33] Reimagine Main Street (December 2020). “Business Owners of Color and COVID-19 Survey.” Retrieved from: https://www.publicprivatestrategies.com/Business-Owners-of-Color-Covid-19-Survey

[34] Kramer Mills, Claire & Battisto, Jessica (August 2020). “Double Jeopardy: COVID-19’s Concentrated Health and Wealth Effects in Black Communities.” Federal Reserve Bank of New York. Retrieved from: https://www.newyorkfed.org/medialibrary/media/smallbusiness/DoubleJeopardy_COVID19andBlackOwnedBusinesses

[35] Ibid., p. 2

[36]Reimagine Main Street (December 2020). “Business Owners of Color and COVID-19 Survey.” Retrieved from: https://www.publicprivatestrategies.com/Business-Owners-of-Color-Covid-19-Survey

[37] Richardson, Jason, Mitchell, Bruce & Edlebi, Jad (December 2020). “NCRC Paycheck Protection Plan Preliminary Analysis.” National Community Reinvestment Coalition. Retrieved from: https://ncrc.org/ncrc-paycheck-protection-plan-preliminary-analysis/

[38] Fairlie, Robert (August 2020). “The Impact of COVID-19 on Snall Business Onwers.” Wiley Online Library. Retrieved from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/jems.12400?af=R

[39] McKinsey & Company (April 2020). “COVID-19: Investing in Black Lives and Livelihoods”. P. 15. Retrieved from https://www.mckinsey.com/~/media/mckinsey/industries/public%20sector/our%20insights/covid%2019%20investing%20in%20black%20lives%20and%20livelihoods/covid-19-investing-in-black-lives-and-livelihoods-report.pdf

[40] Ibid.

[41] Yelp Economic Average (September 2020). “Yelp: Local Economic Impact Report.” Retrieved from: https://www.yelpeconomicaverage.com/business-closures-update-sep-2020.html

[42] Association for Enterprise Opportunity (AEO) (2017). “The Tapestry of Black Business Ownership in America: Untapped Opportunities for Success”, p. 11. Retrieved from https://aeoworks.org/images/uploads/fact_sheets/AEO_Black_Owned_Business_Report_02_16_17_FOR_WEB.pdf

[43] Yelp Economic Average (September 2020). “Yelp: Local Economic Impact Report.” Retrieved from: https://www.yelpeconomicaverage.com/business-closures-update-sep-2020.html

[44] Noel, N., Pinder, D., Stewart III, S., & Wright, J. (2019, August). The Economic Impact of Closing the Racial Wealth Gap. McKinsey & Company.

[45] Bank Black USA. Retrieved from: https://bankblackusa.org/

[46]Kamensky, John (February 2019). “How the Government Could Successfully Leverage Its Buying Power.” Government Executive. Retrieved from: https://www.govexec.com/management/2019/02/how-government-could-successfully-leverage-its-buying-power/155014/

[47] Sanberg, Joe (2019). “Medicare for All is Not Just Good Politics – It’s Good for Business, Too.” The Nation. Retrieved from: https://www.thenation.com/article/archive/medicare-for-all-universal-healthcare/ see also https://youtu.be/Mu5XHBVjDMY