The entire Canadian housing and mortgage market has dropped off a financial cliff, which should pose as a warning for the U.S. as we talk about reforming our Government-Sponsored Enterprise (GSE) system.

In 2008, when the U.S. was entering a full housing market crash, Canada took several steps to disguise the exposure of Canadian households. The biggest Canadian banks (referred to as the Big Six) were given the authority to issue “covered bonds,” mortgage-backed securities that enjoyed an explicit government guarantee. Also, the adjustable rate mortgage system that Canada and most of the world uses benefitted from the rock bottom interest rates that the crash triggered.

Canada’s hottest housing markets, particularly Vancouver and Toronto, also saw a massive influx of foreign investment. This drove median prices in Vancouver to $1 million for condos and over $3 million for single family homes in large sections of the city.

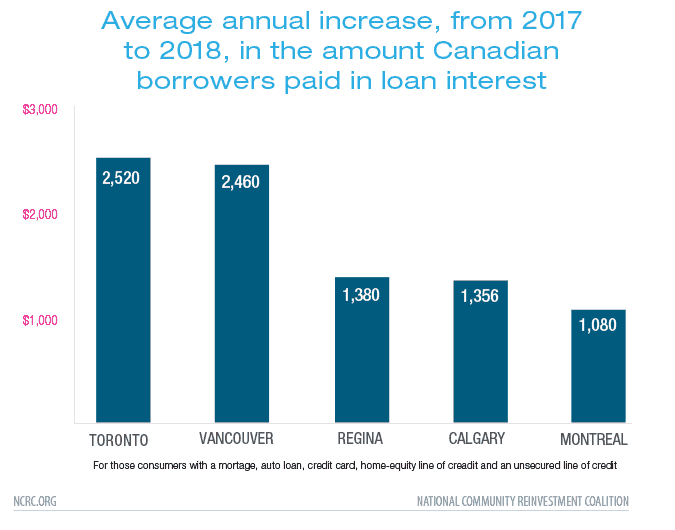

In response, Canadian households went further and further into debt to keep up, with Vancouver families averaging debts over 17 times their average income. Now that interest rates are rising, many households are finding they cannot meet their monthly payments. Couple this with new taxes aimed at discouraging foreign speculators and rules that require lenders to verify the ability of borrowers to actually repay their debts, and the entire Canadian market is reeling.

(Source: CMHC, Maclean’s)

The effect on homeowners is brutal, as their home values are dropping fast while the amount they pay for their mortgages is skyrocketing. Meanwhile, wages remain stagnant and banks are getting stingier with new loans and more aggressive with defaulters.

This unfolding debacle offers cautionary guidance for the U.S. as we talk about GSE reform in 2019.

The 30-year fixed-rate mortgage is often criticized for its cost. Borrowers pay more for a fixed-rate loan so lenders don’t need to worry as much about changes in mortgage rates. The flip side is that homeowners know what their payments will be, and once they buy a home they are insulated from the impact of broader economic trends like rising rates in ways that Canadian households are not.

In the U.S., the GSEs (Ginnie Mae, Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac) have been the sole producer of mortgage backed securities that enjoyed a public guarantee. When Canada allowed their Big Six banks to issue their own securities with government insurance, it simply added fuel to the conflagration that was engulfing their housing markets. As the debt underlying those bonds begins to default, Canada will be on the hook with investors. Those who want to see Fannie and Freddie wound down here in the U.S. envision a similar system where big banks can use the single securitization platform to package and sell their own securities, potentially flooding the market with loans.

It is tempting to look at Canada’s crisis and shrug it off as not impacting the U.S. But in the face of proposals to radically reform our housing system to look more like Canada’s, their troubles should be closely watched and considered.