Key Findings

- Better outcomes on the retail lending test usually corresponded to higher ratings but the differences in performance were not as wide as expected

- Performance measures used to assess community loans and investments tended to indicate greater differences in bank performance across ratings categories

- This paper suggests the need for refining performance measures and associated ratings instead of a radical overhaul proposed by the agencies

Executive Summary

As a first step for assessing whether reform for the Community Reinvestment Act (CRA) is necessary, analysts should ascertain whether CRA ratings correspond to significant differences in performance. If they do not, then either refined or new performance measures need to be developed. This report utilized a new Federal Reserve database of a sample of 6,300 CRA exams conducted during 2005 through 2017. The database contains data for bank performance for assessment areas (AAs), or geographical areas containing bank branches.

This analysis first tested whether retail loan performance measures such as the percent of home loans to low- and moderate-income (LMI) borrowers are higher for better ratings on the lending test, one of the major components of CRA exams. We found that, in general, better outcomes corresponded to higher ratings for retail loan performance measures but that the differences in performance tended to be not as wide as expected. In contrast, measures used to assess community development loans and investments tended to indicate greater differences in bank performance across ratings categories.

The results suggest the need for refinement of performance measures, especially for the retail loan indicators, rather than a complete overhaul. The Federal Reserve data indicates a rating system that is not fundamentally broken or arbitrary but a system that should be sharpened. We suggest a more explicit sorting of bank performance into different ratings categories based on how banks perform against their peers and that more testing should be conducted to assess whether different peer benchmarks should be developed for banks with different business models.

In addition, the findings argue for retention of qualitative factors and allowance for performance in one area to compensate for poorer performance in other areas, but also for more explicit methods for indicating how the qualitative factors and compensation procedures contribute to ratings. Nonetheless, even when accounting for qualitative factors, the quantitative performance measures used on CRA exams should indicate significant median differences in performance across ratings categories.

The Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC)’s final rule for changing the CRA regulations does not employ a careful data-based assessment of the nature considered in this report. Although the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) signed on to the proposed rule, they pulled out of the final rulemaking. The OCC should withdraw its final rule and embark on a new one with the Federal Reserve Board and the FDIC.

Introduction

Banks and community groups have advocated for the reform of the CRA regulation in part because of concerns related to the subjectivity of CRA ratings. If CRA ratings do not reflect differences in actual bank performance in lending, investing and providing bank services to LMI communities, CRA will not achieve its fullest potential in increasing lending, investing and services to underserved borrowers and communities.

In order to reduce subjectivity in CRA ratings, must CRA ratings and exams be radically overhauled as executed by the OCC’s final rule? Alternatively, would incremental reforms be more effective? The bottom line is that a ratings system should accurately reflect differences in performance so that the banks with lower ratings would be motivated to increase their lending, investments and services to LMI borrowers and communities.

A substantial body of research has found that CRA has been effective in increasing access to credit and capital for LMI borrowers and neighborhoods. Economists at the Federal Reserve Bank in Philadelphia found that CRA increased home lending in LMI neighborhoods by up to 20%. Bostic and colleagues revealed that CRA also increased small business lending. Ding and Reid showed that CRA prevented the closure of profitable branches in LMI census tracts.

Clearly, CRA has motivated banks to serve LMI communities. While this report was not designed to offer estimates regarding the extent to which CRA has reached its potential to increase access to credit and capital, it did examine whether the rating system can be improved, which in turn would increase access to credit and capital for underserved communities.

NCRC utilized the recently released Federal Reserve database on CRA exams conducted between 2005 and 2017 for this report. Our recent comment letter to the OCC and FDIC described the database in detail.

Findings

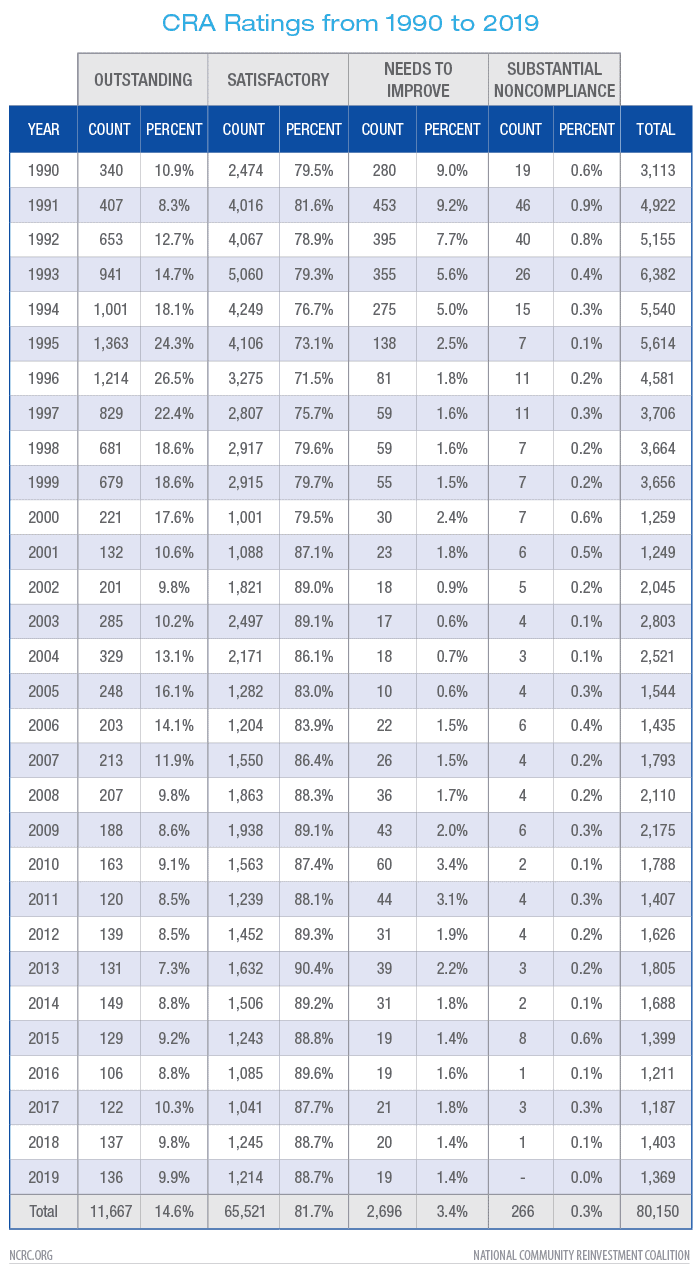

Overall Ratings

Table 1 below shows that overall CRA ratings could be improved in terms of differentiating bank performance. For example, it is unlikely that upwards of 90% of banks performed in a Satisfactory manner as recorded by CRA ratings over the last several years. On the other end of the ratings distribution, the portion of banks that failed their exams (Needs-to-Improve and Substantial Noncompliance) dropped from a high of 10% in the early years of public disclosure of ratings to 2% or less in recent years.

A shortcoming in the ratings system is that four ratings are the only possible overall ratings. Five ratings would allow for more distinctions in performance. The large bank exam has a lending test, an investment test and a service test. Each of these tests would have five overall ratings: Outstanding, High Satisfactory, Low Satisfactory, Needs-to-Improve and Substantial Noncompliance. If the overall ratings divided the current Satisfactory rating into High and Low-Satisfactory, the 90% of banks that had scored Satisfactory would now be divided into two buckets, which would better reflect their performance.

The OCC hesitated to establish five overall ratings, citing the CRA statute that lists just four ratings. However, it could establish point scales that would more effectively differentiate the performance of the banks with Satisfactory ratings. On a point scale of 1 to 100, for example, banks with Satisfactory ratings could have points ranging from 60 to 90; those with scores of 60 to 75 would have Low Satisfactory ratings and those scoring 76 to 90 would have High Satisfactory ratings. Alternatively, if Low and High Satisfactory were not assigned to point ranges, it would still be clear that banks scoring lower on the point scale were performing in a manner that is not quite Satisfactory.

Ratings on Retail Part of Lending Test and Performance Measures

The lending test uses various performance measures to assess a bank’s retail lending performance. For home lending, two of these measures are the percent of loans to LMI borrowers and the percent of loans in LMI tracts. For small business lending, the two measures are percent of loans to the smallest businesses (revenues less than $1 million) and percent of loans in LMI tracts.

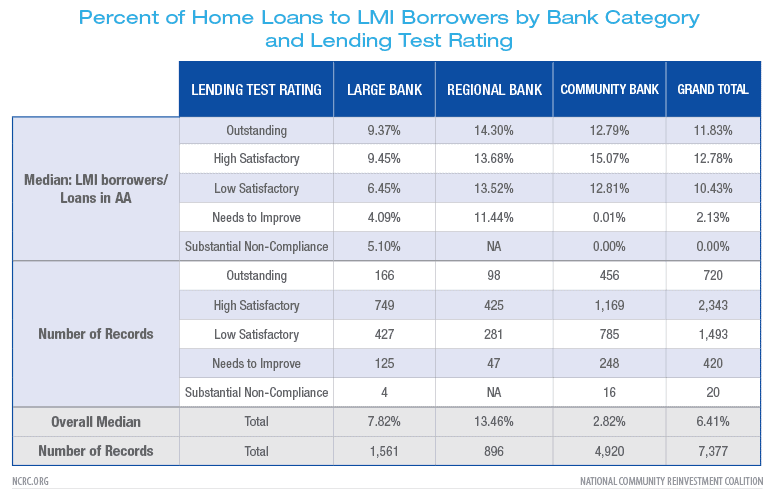

Table 2 tests the relationship between the five ratings on the lending test and percent of loans to LMI borrowers. At the outset, it is important to remember that there may not be a perfect relationship between ratings and percent of loans. Higher percentages of loans on one performance measure may not always translate into higher ratings since the lending test has several measures. Also, it is possible for a bank to compensate for poor performance on one measure with better performance on another measure. However, the median percentage of loans to LMI borrowers should be generally different for banks with different ratings, particularly over a large sample size.

This examination also split banks into different asset categories to see if different relationships emerge between ratings and performance for the different asset categories. Following the methodology of Calem, Lambie-Hanson and Wachter described in our comment letter to the OCC and FDIC, NCRC classified the banks as community banks with assets up to $10 billion, regional banks with assets between $10 billion and $50 billion and large banks with assets over $50 billion. This report did not include findings for banks with Substantial Noncompliance ratings since there are too few observations for these banks.

A highly visible finding in Table 2 was that large banks issued a considerably lower percentage of loans to LMI borrowers from 2005 through 2017 than their smaller counterparts. Some large banks have stated that their higher loan volumes makes it harder for them to perform as well on a performance measure of percent of loans to LMI borrowers. Also, large banks could be performing better on other parts of the lending test. However, this finding suggested that there is room to rate large banks more rigorously on the lending test and on this particular measure.

Another clear finding was that the percentage of loans to LMI borrowers for banks with High Satisfactory ratings was higher than the percentage of loans to LMI borrowers for banks with Outstanding ratings. For banks in all categories, the median percentage of loans on an assessment area (AA) level to LMI borrowers was 11.83% for banks with Outstanding ratings and 12.78% for banks with High Satisfactory ratings. Performance on other performance measures might be compensating in the case of banks with Outstanding ratings. However, the question remains whether at the median, the scoring system could more effectively and logically differentiate banks in these two ratings categories with Outstanding banks achieving higher ratings.

Except for regional banks, banks with High Satisfactory ratings issued a higher median percentage of loans to LMI borrowers at an AA level than banks with Low Satisfactory ratings. The difference was generally two to three percentage points between the two ratings.

The sharpest differences in performance occurred between banks with Low Satisfactory ratings (10.43%) and banks with Needs-to-Improve ratings (2.13%). Banks with Needs-to-Improve ratings were making few loans to LMI borrowers.

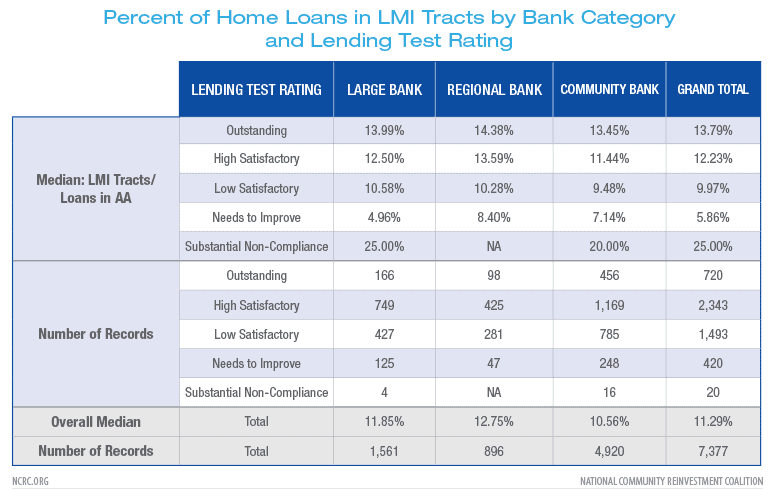

Table 3 results were more consistent with expectations. For each bank category and overall, the median percentage of loans in LMI tracts at the AA level was higher by one to two percentage points for banks with Outstanding than High Satisfactory ratings. A similar difference occurred between banks with High Satisfactory and Low Satisfactory ratings. Finally, a stark difference in median percentage of loans in LMI tracts occurred between banks with Low Satisfactory and Needs-to-Improve ratings.

Large banks did not perform worse than their smaller counterparts in percent of loans in LMI tracts in contrast to percent of loans to LMI borrowers. This does not necessarily absolve large banks since it is arguable that LMI tracts is an easier performance measure since a portion of lending in LMI tracts is to middle- and upper-income borrowers.

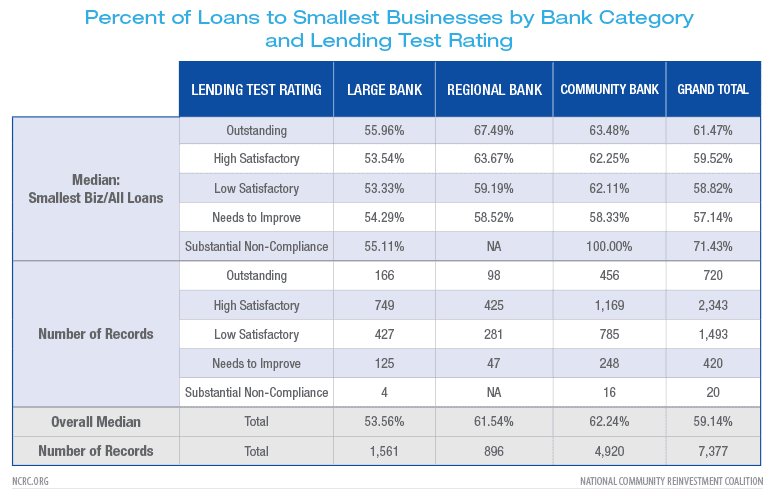

Table 4, examining lending to the smallest businesses with revenues below $1 million, revealed a different result than Table 3 in that the median percentages of loans at the AA level to the target population was not noticeably different across ratings categories. The difference between all banks with Outstanding ratings compared to banks with High Satisfactory ratings was about two percentage points (61.47% vs. 59.2%). However, the regional banks could be responsible for a significant amount of this difference; the performance of regional banks with Outstanding and High Satisfactory ratings differed by four percentage points whereas the difference was narrower for the other two bank categories. Again, except for regional banks, the difference between High and Low Satisfactory ratings in the portion of loans to the smallest businesses was less than one percentage point. Finally, it was only the community bank category that exhibited a sizable difference in the percent of loans to the smallest businesses between banks in Low Satisfactory and Needs-to-Improve ratings.

Another notable finding was that large banks trail their counterparts in lending to the smallest businesses. For example, regional banks with Outstanding ratings issued a median percentage at the AA level of 67.49% of their loans to the smallest businesses compared to large banks’ median of 55.96%. This was consistent with the home lending results. Large banks had the most difficulty relative to their peers in lending to borrowers with the lowest incomes or revenues than in lending to LMI tracts.

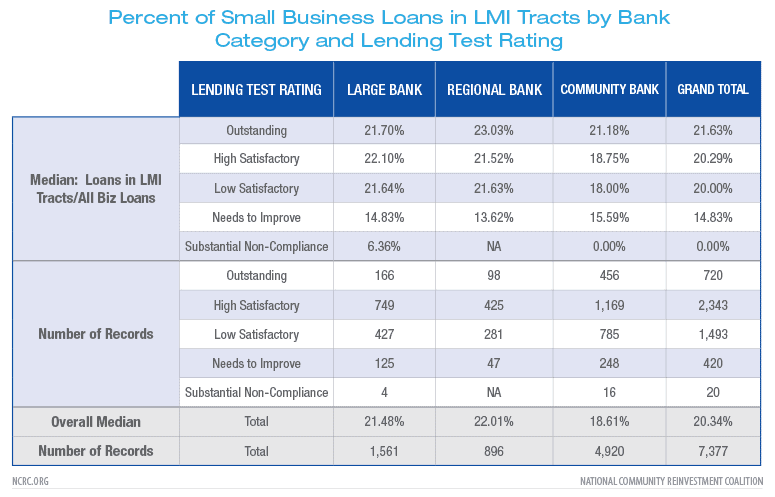

Table 5, revealing the median percent of loans to small businesses in LMI tracts at the AA level, continued the theme of expected differences between the rating categories but differences of small magnitudes and inconsistencies across the various bank asset categories. Overall, the difference between banks with Outstanding and High Satisfactory ratings in the portion of loans in LMI tracts was about one percentage point, with greater differences between regional and community banks than large banks. There were muted differences of less than one percentage point between banks with High Satisfactory and Low Satisfactory ratings. Finally, there were pronounced differences of more than five percentage points between banks with Low Satisfactory and Needs-to-Improve ratings.

Another measure of performance on the lending test is the amount of community development (CD) loans. CD loans finance larger scale projects than individual homes or loans for small businesses. CD loans support affordable housing (often multi-family, rental housing), larger scale economic development projects or initiatives that revitalize and stabilize LMI communities.

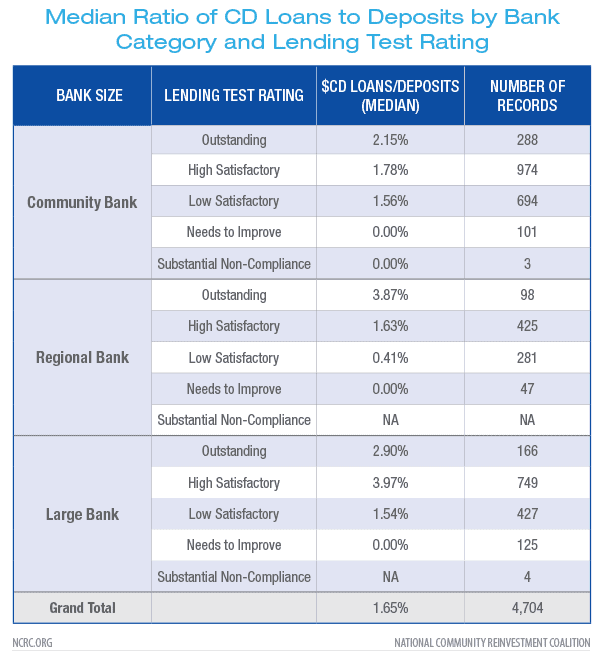

Table 6 displays a ratio of CD loans by deposits, which is similar to ratios used on the lending test. For regional and community banks, it showed that higher ratios corresponded to better ratings as to be expected. Moreover, the differences in the ratios for the rating categories were more pronounced than for the measures used for the retail part of the lending test described above. For example, the median CD loan ratio at the AA level of regional banks with Outstanding ratings was 3.97%; 1.63% for those with High Satisfactory ratings; and .41% for those with Low Satisfactory ratings. Expressed another way, the median ratio for banks with Outstanding ratings was 137% higher than the ratio for High Satisfactory banks, which was in turn 297% higher than the ratio for Low Satisfactory banks.

Another way to consider the significant differences in ratios for banks with different ratings is to remember that they express the percentage of deposits devoted to CD lending. Banks with Outstanding ratings were devoting 137% more of their deposits to CD loans than banks with High Satisfactory rating. This was a much more significant difference than a retail performance measure that differs by one percentage point between banks with different ratings: one percentage point or a difference of 20% vs. 21% of loans is a considerably smaller difference in resources for a LMI population than 100% more deposits devoted to CD financing.

The median ratios for community banks were quite different for Outstanding and High Satisfactory banks (2.15% vs. 1.78% for a 20% difference). The differences for those with High and Low Satisfactory ratings were somewhat narrower.

Large bank ratios had an unusual pattern with median ratios for banks with High Satisfactory ratings being higher than those with Outstanding ratings. However, the differences between the other ratings were in the expected direction and were large. A possible explanation for the unusual position of banks with Outstanding and High Satisfactory ratings is that some very large banks were downgraded for fair lending violations during the years of the financial crisis.

Overall, the differences were larger for the CD part of the lending test than on the performance measures of the retail test. It is possible that the CD measure is a deciding factor determining ratings on the lending test.

Ratings on investment test and levels of community development investments

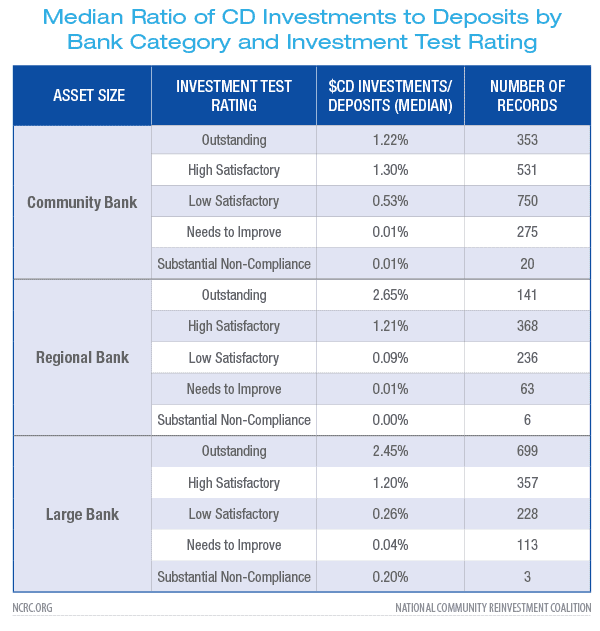

The dollar amount of investments is a significant criterion on the current investment test. CRA exams often measure this activity by reporting overall dollar levels but also comparing investments to assets or Tier One capital. This study used a ratio of community development (CD) investments divided by deposits since assets cannot be apportioned easily at the AA level and since the OCC finalized the use of deposits in the denominator of their CRA evaluation measure.

In contrast to the retail portion of the lending test, differences across rating categories were more pronounced except for the top two ratings in the case of community banks. The median ratio at the AA level for community banks was 1.22% for those that received Outstanding on the investment test and 1.3% for those that received High Satisfactory. The median ratio for community banks rated Low Satisfactory nosedived to .53% and was a mere .01% for community banks rated Needs-to-Improve.

Regional and large banks exhibited wide differences among the ratings categories. Large banks with Outstanding ratings had a median ratio at the AA level of 2.45% while those with High Satisfactory had a significantly smaller ratio of 1.2%. A very similar difference was present for regional banks. The ratios for banks in those two categories with Low Satisfactory and Needs-to-Improve ratings were quite small.

Implications of Findings

Generally, the analysis found expected differences among banks with various ratings on retail test performance measures but differences were often narrow. The analysis revealed some inconsistencies like higher percentage of loans to LMI borrowers for large banks scoring High Satisfactory rather than Outstanding. The anomalies in the large bank ratings could be explained by some very large banks being downgraded during the financial crisis for violations of fair lending and consumer compliance law as discussed above.

Large banks significantly trailed their smaller peers in percent of loans to LMI borrowers and smallest businesses. This difference in performance did not occur when considering lending in LMI tracts. It seems that ratings could be tougher on these performance measures in order to encourage large banks to increase their percentage of loans to these categories of borrowers.

The other major finding was that the performance measures for CD lending and investment generally revealed larger differences among banks with various ratings than the measures for the retail portion of the lending test. While the median percent of retail loans generally varied by a percentage point among the ratings, the differences in the CD loan and investment ratios were often as high as 100%.

The ratings methodology on the retail portion of the lending test could be improved. NCRC suggests an approach that awards a rating based on how a bank compares to its aggregate peer or peer group of lenders. The percentages below indicate how a bank’s percentage of loans to a borrower group compares to the peer. For example, if the peer group issued 20% of loans to LMI borrowers, the bank would need to issue more than 20% of loans to LMI borrowers in order to score Outstanding on the performance measure. Below are possible ranges relative to the aggregate peer performance:

Outstanding: greater than 100% because the bank would be better than its peers.

High Satisfactory: 80% to 99% because the bank would be approximately in line with its peers.

Low Satisfactory: 60% to 79% because the bank would be below its peers, but not so far below to be considered not satisfactory.

Needs to Improve: 40% to 60% because the bank would be at approximately half the level of its peers.

Substantial Noncompliance: 39% and lower because the bank would be far below the level of its peers.

Another decision would be what groups of banks would constitute the “aggregate peer.” CRA exams currently consider all lenders reporting HMDA or CRA data at the AA level to be the aggregate peer. In recent research, NCRC found that banks with branches in an AA tend to lend at higher percentages than those without branches in an AA. Banks without branches could be credit card banks in the case of small business lending, internet-based banks or banks using correspondents or brokers in the case of home lending.

A legitimate question is whether banks with different business models should be expected to perform at the same level on a performance measure or whether that is not possible because the different models make them good at some aspects of CRA performance and not as good at others. In the initial years after a change to the CRA regulation and exams, it might make sense to use different peer aggregates for branch-based institutions and non-branch ones. It would not make sense to fail non-branch banks if they are far behind their branch-based peers on the retail loan performance measures. However, their scale above could be adjusted so fewer of them are obtaining Outstanding and High Satisfactory ratings since they are not performing as well on retail loan performance measures as their branch-based peers. Over time, it is hoped that the performance converges to a higher level for banks of various business models. Future rule makings could then adjust peer aggregates and scales.

In addition to the differences in performance between branch-based and non-branch based banks, the agencies should see if there are significant differences revealed by the performance measures among banks with various asset levels. If there are differences, the agencies should make any appropriate adjustments to aggregate peers.

This paper did not analyze demographic measures that include comparing the percent of home loans to LMI borrowers to the percent of households in an AA that are LMI. Empirical testing similar to that presented in this paper should test performance on demographic measures. In a previous report, NCRC found high rates of failure for a demographic measure proposed by the OCC and FDIC. Perhaps one refinement could be to compare a bank’s performance against aggregate peer performance on a demographic benchmark using a scale similar to that above.

Further complications to ratings in current CRA exams are qualitative factors and allowance of performance in some tests to compensate for lackluster performance in other tests. CRA should not be a strictly quantitative exercise because responsiveness to unique needs and different economic conditions in different AAs cannot be captured in performance measures such as percent of loans to LMI borrowers. NCRC stated in its comment letter that qualitative measures capturing responsiveness, innovation and flexibility should count for 20% to 30% of the rating on a test. In addition, within reason, a higher score on one component test could compensate for a lower score on another component test. For instance, if internet-based banks are not as successful in retail lending to LMI borrowers, perhaps they should be expected to offer higher levels of CD finance or service. Various weights for each component test builds in compensation.

Even with qualitative and compensating factors as part of component tests, medians of performance measures over a large sample of several years at the AA level should reflect larger differences than observed in the measures of the retail test. The scale suggested above could achieve that. The only way to assess this possibility is for the OCC to have collaborated in designing even more comprehensive databases than the Federal Reserve did and then to test rigorously different approaches with the database. While the Federal Reserve pioneered an effort and created a database that had not ever been collected before, the database did not include variables for all three major component tests. Service test variables such as the percent of branches in LMI tracts were missing. It is possible that three agencies combining resources could have created a more thorough database.

Conclusion

Using Federal Reserve data on a large sample of CRA exams, this analysis found that CRA ratings reflect actual differences in bank performance on the retail lending test and the investment test. The performance measures, particularly those related to the retail lending test, should be sharpened so that they more clearly differentiate performance as reflected in CRA ratings. The overall objective is to reform the present ratings system, in which 90% of banks receive one rating that is Satisfactory, when it is clear that there are more differences in performance than revealed by the current system. An update to CRA, rather than the radical overhaul as finalized by the OCC, would achieve meaningful ratings reform.

In particular, ratings for large banks should be toughened. NCRC found that they considerably lagged their smaller counterparts in the percentage of loans to LMI borrowers and to the smallest businesses. This finding was similar to that in the Calem, Lambie-Hanson and Wachter study mentioned above.

The OCC’s final rule is not evidence-based. The OCC’s final rule is not based on data analysis nor does it include a publicly available database like the Federal Reserve made available. Stakeholders cannot estimate its impact using data on lending, investing and service provision. It must be withdrawn to allow for a more thoughtful and data driven rulemaking to proceed.

After implementation of a new regulation and examinations, the agencies should produce annual reports that include analyses of performance measures along the lines of this analysis and indicate whether the performance measures are working as desired or whether further changes are needed.

Methodology Appendix

The Federal Reserve used HMDA data for calculating the number of loans to various borrower groups inside AAs and outside AAs. We used the HMDA data for inside AAs since CRA exams measure home lending inside AAs. The small business data collected by the Federal Reserve did not always include separate totals for inside AAs so we used the lending data labeled as “total” when there was no data for inside AAs for a borrower group.

NCRC used all banks up to $10 billion for community banks for the lending test, but stripped out intermediate small and small banks in this category for the investment test and for the community development lending analysis. Small banks are not evaluated for community development financing and intermediate small banks do not have an investment test.

The Federal Reserve database did not contain variables related to the service test such as the percent of branches in LMI tracts. Therefore, we could not assess service test ratings compared to performance measures.

Josh Silver is NCRC’s Senior Advisor, Policy and Government Affairs.

Jason Richardson is NCRC’s Director of Research & Evaluation.