Rita T. Harris, Sierra Club National Board of Directors

This is one in a series of essays accompanying NCRC’s 2020 analysis that showed more chronic disease and greater risks from COVID-19 in formerly redlined communities. The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views or policy positions of NCRC.

Introduction

I have lived in or near Memphis, Tennessee, since I was born, and I’ve worked for the Sierra Club locally for over 20 years. A new report from the National Community Reinvestment Coalition highlights the national impact of redlining and segregation on the health of Black communities and how that equals an increased COVID-19 vulnerability. In this blog post, I will discuss how those findings relate to the history of racism and environmental justice with a focus on Memphis.

When I first started organizing Black and/or low-income communities in the early 1990s, neighborhood residents were concerned with various environmental justice issues like air pollution around manufacturing plants and factories, rumors of illegally buried waste, contaminated water wells and a federal facility with contaminated groundwater that threatened the local drinking water supply. Generally, community residents were concerned about environmental hazards and how pollution coming from industrial facilities threatened their health. In the early 1990s, there were numerous large industrial facilities including a coal-fired power plant that spewed toxic pollution into the air every day. For years, Memphis ranked as an asthma capital, affecting the vulnerable poor and elderly residents.

Despite there being environmental laws in place in the 1990’s that gave individuals and community groups the right to request information about companies’ activities, including what they were making and what chemical substances were used in the process, city and county officials did not want to share information. It was a constant battle. Often Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) requests were used to get records from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and state agencies about industrial plants and the chemicals they used, stored on site and disposed.

Fortunately, today, the ability to gather information from agencies has largely improved. However, the fight for strong environmental protection, faster cleanup solutions and the basic enforcement of regulations and laws continues. And, with the Trump Administration’s rollback of numerous environmental laws that were put in place to better protect environmental justice communities, the task of protection is far more difficult.

Environmental justice (EJ) is a term that speaks to our vision of a safe, healthy and just community. It encompasses where we live, work and play. The ideology of environmental justice does not support placing unwanted dangerous facilities in any neighborhood. EJ supports and advocates for strongly enforcing environmental laws that protect human health through finding safer chemicals, testing chemicals before they are put on the market, using safer substitutes when available and cleaning up polluted locations in a timely manner.

Black communities across the U.S. are inundated with negative health impacts that arise from living dangerously close to oil refineries, high traffic areas and highways crisscrossing communities, coal-fired power plants, medical waste incinerators, Superfund sites with legacy waste issues, railroad tracks that transport chemicals and dangerous cargo, landfills and illegal dumpsites. Why are these kinds of facilities most often in poor and people of color neighborhoods in America?

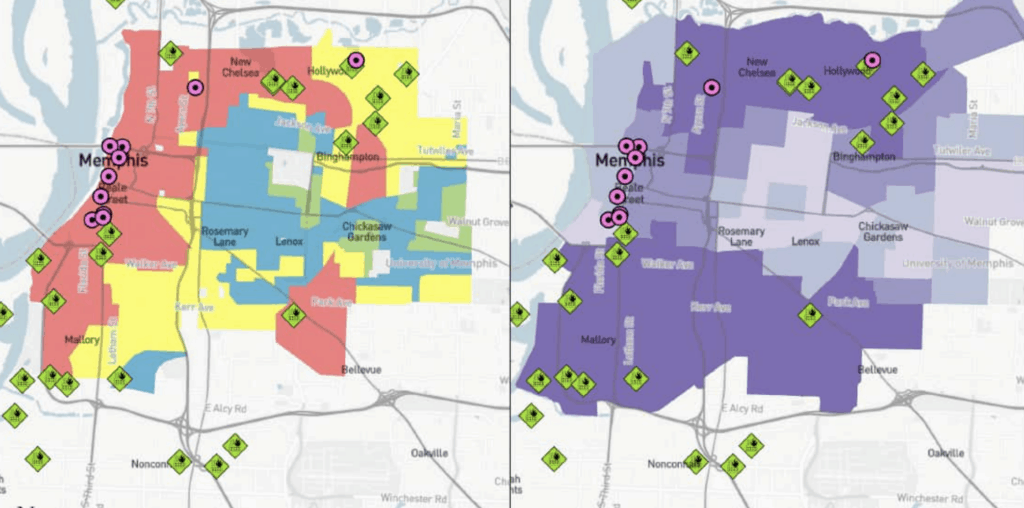

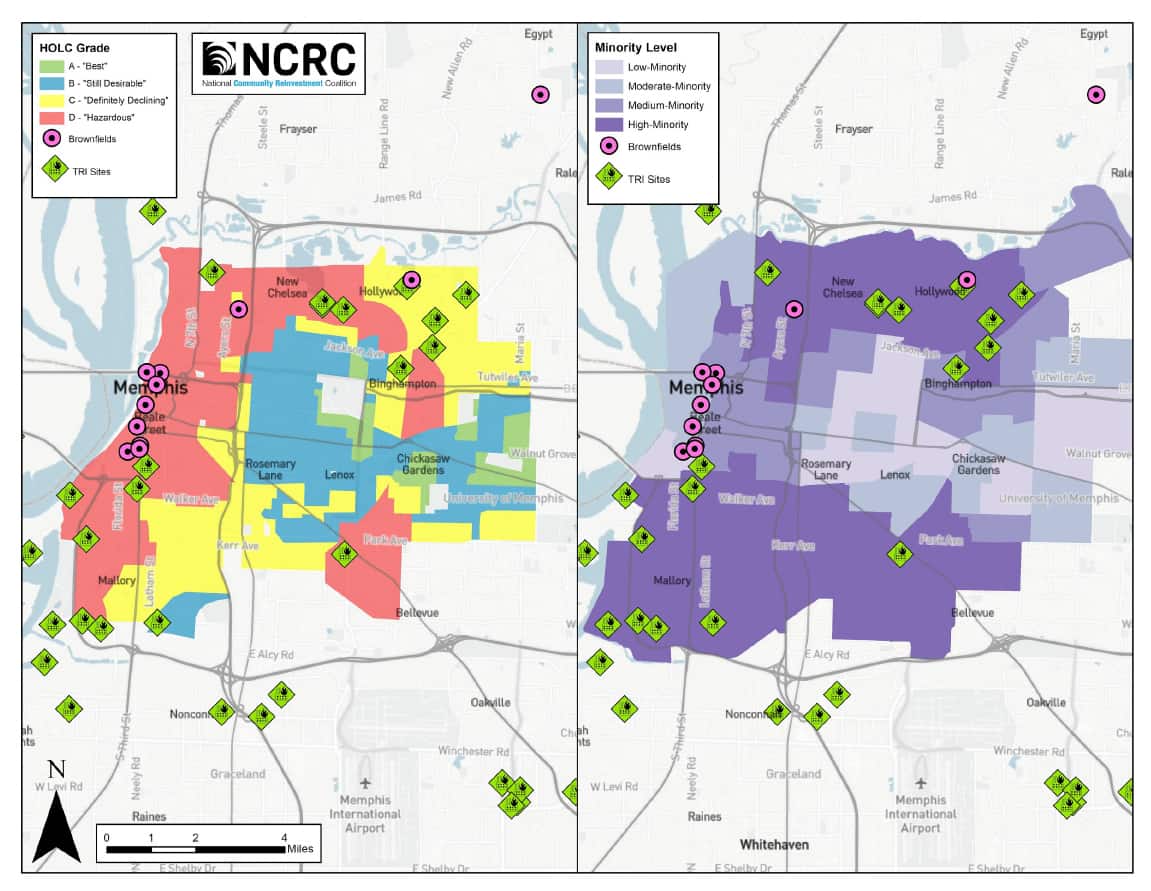

In Memphis, the Sierra Club Environmental Justice Program, which ran from 1999 to 2017, did a mapping project that highlighted polluting industries in Shelby County, pointing out the location of children and their schools, railroad tracks that transported dangerous cargo, highways crisscrossing communities, medical waste incinerators and Superfund sites. Unsurprisingly, these sites were located primarily in Black neighborhoods. Like most American cities, Memphis has a long history of racist housing and environmental policies. As this report from NCRC and its university partners shows, this history has real world impacts today, resulting in worse health outcomes for Black neighborhoods, shorter lifespans, poorer overall health and greater risk of several complications due to COVID-19.

How did this come to be?

Map of Memphis and Toxic Release Inventory and Brownfield Sites

Memphis and Segregation

Understanding the pervasive nature of segregation and racism that fueled Jim Crow helps explain the term environmental racism. When decisions were made about where to locate a dirty business, a polluting industry or even a place for a dumpsite, the best place was usually in and around low-income or African American neighborhoods throughout urban U.S. The given excuse was that the land was cheaper and better suited for industrial uses.

In Memphis, when I think of where all the major polluting manufacturing plants have been located, they are indisputably in or near an African American neighborhood. Some people have argued that these residents of Memphis don’t mind living near the railroad tracks or industrial plants. This argument doesn’t go very far if the question is asked, “Why were the African American neighborhoods near these places in the first place?” The land was cheap, undesirable and somewhat out of sight, much like the poor homeless shanty towns we see in cities today. Jim Crow laws were meant to keep Whites and Blacks separated in every facet of their lives and reserved what they considered the best for the Whites, particularly when it came to land ownership.

Like many southern cities, Memphis is still a mostly segregated city, and has been as far back as I remember. It is important to understand why this came to be. Memphis is built high on the bluffs of the Mississippi River. It became prosperous and strong from river commerce and cotton businesses. The earliest residents settled in the downtown area close to the Mississippi River. Later, they branched out along what is now Central Avenue and Peabody Avenue, and then even further outward towards East Memphis and Germantown. The historic areas of Memphis still feature some of the homes that wealthy residents of the early period built, such as those in Victorian Village. African American residents were relegated to neighborhoods on the outskirts of town, across the tracks, out of sight and out of mind. Often, these areas included industrial facilities like factories, riverfront businesses and railroads tracks. Despite this early history of de facto segregation, it was de jure racial and economic segregation over several decades that is a primary reason why neighborhoods remain segregated today.

For those who have a difficult time accepting the fact that devious minds perpetuated and supported legalized segregation for decades, I recommend a book that supports not only this point as factual, but discusses just how deeply rooted the practices and policies of legal racial residential segregation actually were. Remnants of this kind of policymaking and city planning still exist. In Richard Rothstein’s book, The Color of Law, it is quite troubling to read the lengths our own government went to secure and control the demise of African Americans while propping up the continuation of White dominance. According to this book, it was never intended for African Americans to achieve the American Dream.

We all know that the racist system of Jim Crow institutionalized segregation and all that went with it: poor or no city services, lack of zoning regulations, poor streets, unkept parks, lacking or lax environmental regulations, etc. City services and county services were sorely needed. Over the years, improvements were made but not at the same pace as seen in the more affluent parts of town.

It is because of these policies and practices that when manufacturing businesses were booming in Memphis back in the 1970s and 80s, and it seemed like everyone that wanted a job had a job, not everyone had the same opportunities to move to “better” or healthier neighborhoods. These good jobs allowed many White residents to move out of poor neighborhoods, become upwardly mobile, and buy a home in the suburbs or in ‘better’ parts of the city. However, I personally recall the excitement of many prospective home buyers of color seeking a home near good schools and free from toxic pollution sources to raise their children, and facing challenges in getting a bank to approve their loan.

For my husband and I, it wasn’t too difficult, because the neighborhood we were looking to move to was eager for young upwardly mobile African Americans to move in. More than half of the previous White residents had already started to move out of the Bethel Grove neighborhood. Plus, my husband had a great job with the U.S. Post Office and was a former Air Force sergeant, which meant we could take advantage of the low-cost mortgages provided by the GI Bill when we applied for our home loan.

While the Community Reinvestment Act, the Fair Housing Act, and the Equal Credit Opportunity Act said individuals seeking loans and better homes in better neighborhoods should be able to do so, it just wasn’t happening. At least it wasn’t happening at the same rate as it was for Whites applying for loans. Some wondered if the real estate agents were working with banks to intentionally keep African Americans from getting the necessary loans and moving into certain neighborhoods. Yes, blocking loans and blocking African Americans and other people-of-color from moving into White neighborhoods seemed to be an unwritten rule. Many bankers and decision makers made individual and institutional decisions to slow this process down. This unfair and criminal practice of redlining blocked the entry to White neighborhoods and gave White homeowners financial protection to preserve their property values. Banks and realtors used maps that they circled with red markers and other colors that provided them with a “color code” to immediately know where you could and could not sell to African Americans or other people of color. Assisting African Americans with buying homes in White areas was despised and seen by some as “block-busting” or integrating White communities which in turn caused Whites to move out allowing for more integration. Because of institutionalized racism, systemic practices were determined to stop integration and preserve all-White neighborhoods. Efforts continued even though there were federal banking and housing laws on the books saying people could live wherever they chose to live.

Over the years, racist practices have continued, are more sophisticated, and remain a challenge for communities. The trend of consolidating banks across regions has not simplified the problems associated with fair banking. Banks were supposed to try to meet the credit needs of everyone, including African Americans from low-income communities seeking loans. Thanks to the Home Mortgage Disclosure Act (HMDA), reports can be accessed to track discrimination in lending at individual banks.

Banks must be pushed to service low-income neighborhoods with the placement of full-service bank branches. This remains a concern and the struggle for equity in banking continues. Banks began to quietly support the growth of pay-day loan businesses with high interest rates and check cashing businesses instead of establishing full-service banking locations in low-income areas. These businesses further entrench poverty in areas already struggling to gain footing and find a way to a better life.

Pollution and Race

Given this disparate treatment of Black people, it is no coincidence that Black neighborhoods in Memphis are often the site of ‘environmental insults’ more often than White communities. In 1986, the landmark study Toxic Waste and Race, commissioned by the United Church of Christ Commission for Racial Justice, showed that African Americans were more likely to live near or be negatively impacted by uncontrolled hazardous waste facilities and industrial plants. Since that time, numerous studies have reinforced and expanded on this work, helping us understand that this pattern persists today in Memphis, but also in places like Flint, Michigan. In Flint, persistent and criminal disregard for Black lives poisoned Black neighborhoods with lead in their drinking water. In Memphis, we see an increase in permit requests for construction landfills in and around neighborhoods instead of locating them in areas away from homes, churches and schools. Community residents that want to protect their health, well-being and their property values are organizing to stop this development.

Although not in all cases, the practice to place these environmentally hazardous facilities in neighborhoods is perpetuated by decision makers who feel that because similar facilities are located there, it is the obvious best place for a new one. This kind of thinking is what has caused EJ communities to have a disproportionately high number of environmental issues/problems in certain geographic tracts. EJ communities do not have the luxury of fighting or challenging just one problem; in some cases there are numerous issues negatively impacting one neighborhood.

While the location of dirty facilities is an issue, there are also problems associated with environmental enforcement of regulations and laws. Once a problem has been identified, sometimes it takes years to get the attention of agencies in charge of remediation or cleanup. And, even then, the remedies are often seen as weak, insufficient and could take years to complete.

Memphis has an over-abundance of old housing stock that has lead paint problems that date back many decades. Although efforts to improve community education and childhood lead testing are better now, both still remain a serious concern. In one community in South Memphis, where a secondary lead smelter operated for over 40 years, children were never adequately tested. Pollution released from the lead smelter, now closed and removed from the community in 1999, wasn’t the only source of contamination. The community is also a stone’s throw from a massive oil refinery and an interstate highway. Additionally, this neighborhood is less than five miles from Presidents Island, an industrial corridor with industrial plants and once major polluters. This community lived with these burdens for decades.

Health Outcomes

After the Civil War ended, Memphis remained heavily segregated, with disastrous consequences when the Yellow Fever epidemic hit in 1873. The outbreak was so deadly that most of the White residents either died or deserted the city for fear of their lives. But African Americans, already forced to live in parts of the city most vulnerable to swarms of disease carrying mosquitoes, were left to fend for themselves. The exodus of White residents was so extreme that the tax base of Memphis was wiped out, and the city was unable to service its debt. In 1879 this resulted in the state revoking the charter that made Memphis a city. It was then that Robert Church, one of the first Black American millionaires, stepped in and saved Memphis. Robert Church bought up many of the buildings in Memphis that had been abandoned and built facilities for the Black residents of Memphis. He bought municipal bonds to help the city get back on its feet and in 1891 the city of Memphis was issued a new charter by the state legislature. Given this history, some might wonder why the presence of African Americans were not celebrated more, or why Memphis never evolved into a city of brotherly love instead of the racially divided metropolitan city it is today. But, from the city’s beginnings it was customary in that day to have separate everything, and with Whites being of a higher economic level, having the privilege of having the best of everything.

One of the first memories I have of being treated differently was at school in South Memphis. Although our teachers were great, and held all students to high standards, our school books were old and ragged. Many times we had to share books with other students when pages were torn or missing. When we did get ‘new’ secondhand books, inevitably we would notice the stamp inside that indicated they had been issued originally to a school in a White neighborhood. Although the new books were very nice compared with the ragged ones we had, it was clear at an early age that Whites acquired the best for themselves first, and when they wanted an upgrade then the African American schools could have what they did not want. This treatment, separate and unequal, carried over to all aspects of our lives.

One disturbing result of the history of environmental insults that Black Memphis residents have had to contend with is alarmingly high levels of infant mortality. In the Black neighborhoods of north Memphis, babies die at a rate twice the national average. Lead poisoning is a leading cause of illness among the children of Memphis. The environmental insults of the past continue to kill the children of Black Memphis in 2020.

It’s not a pandemic, it’s a syndemic

Environmental Justice is all about health, the health of our children and the elderly and the overall well-being of our communities. COVID-19 is being characterized as a pandemic however in many poor communities where there are multiple sources of deficiencies, challenges, and health disparities that have already taken a cumulative toll on the lives of children and families, I believe a more accurate term is syndemic rather than pandemic! A syndemic describes a set of diseases that co-occur due to harmful social conditions. Systemic racism in the Memphis area and across the United States has stacked the deck against African Americans, people-of-color, and the poor. There are many factors that impact a community’s quality of life and overall social vulnerability. Poverty and all that goes with it is generational in many areas of Memphis. Education, income inequality, childhood poverty, poor housing, lack of adequate healthcare, living in food deserts, community safety, access to clean air and water, family and social support, affordable safe transportation, energy burden, and safe neighborhoods, systemic racism and others are all impacts that must be factored into the analysis.