In this edition of our Race, Jobs and the Economy series decoding each month’s Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) monthly jobs report, we overview the latest jobs report and comment on the effects of market concentration on inflation and society.

Analysis of Topline Figures in the June BLS Report

The economy added 206,000 jobs in June, a decent pick-up and above the consensus but the good news stops there. The unemployment rate rose to 4.1% – still near historic lows, but also the highest level since late 2021. That uptick in unemployment also continues an unwelcome trend: This is the third straight monthly rise in the jobless rate and indicates a cooling labor market. The 3-month moving average of monthly job gains has slowed to a 17-month low. Additionally, the BLS revised the April and May jobs gains down by 100,000.

Another key job-market indicator – the number of people turning to the unemployment insurance (UI) system they’d previously paid into through payroll taxes – is also souring. Weekly initial jobless claims – which imperfectly track job losses in tighter time increments than other Department of Labor data – approached a one-year high in June. Continuing UI claims – which imperfectly track how difficult people are finding it to get a new job when they lose one – soared to the highest level since the end of 2021.

The Black unemployment rate increased to 6.3%. Though the unemployment rate of Black workers fluctuates month to month, 3-month moving averages that smooth out that noise are nearly a full percentage point higher than the 3-month moving average a year prior.

The unemployment rate for Asian workers increased a whole percentage point to its highest level since October 2021. Typically the Asian unemployment rate is lower than that of their White counterparts, but June defied that trend. White unemployment stood at 3.5%, significantly lower than the 4.1% rate for Asian workers.

Where raw unemployment rates measure how those actively seeking work are faring, a separate metric called the “labor force participation rate” (LFPR) gauges what proportion of a group’s total population are either working or seeking work. Here, June’s numbers are less gloomy: Hispanic LFPR inched up to its highest level since before the pandemic, while the Hispanic unemployment rate remained largely unchanged from May.

The industries with the largest job gains were government (+70,000), health care (+49,000) and construction (+27,000). The government sector’s gains in June were above its average monthly gain of 49,000 over the last 12 months. The public sector has played an ever-increasing role in buoying jobs gains as the government sector has now risen to its highest share of total employment since the end of 2021.

Overall the June jobs report solidifies the consensus that the labor market is cooling. Over the next couple of months if the trends in Black and Asian unemployment continue then the outlook for the future will grow increasingly negative.

There are worrying details in the job data. But where does the economy stand in the wider picture beyond the state of the labor market? Unemployment is only one area of the economy households care about. They also have a particular interest in inflation – defined as the changes in prices for essential goods purchased with income generated in the labor market. Together, labor statistics and inflation data hint at how easy or hard families are finding it to bring money in, and how easy or hard they’re finding it to obtain dignity (let alone luxury) with that money.

Inflation and Market Concentration

The rising prices Americans are paying for everyday items are top of mind for many households, while pundits bemoan their inability to appreciate the drop in inflation from its peak in the summer of 2022. As this disconnect between the political class and the people continues, another debate among economists and policy analysts rages about the role of corporate power and market concentration in driving inflation.

One of the many effects of the inflationary panic of 2022 was a reevaluation of the idea that corporate profits and market concentration could cause or help contribute to inflation. The Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City found corporate profits significantly contributed to inflation in the early half of 2021. The Federal Trade Commission’s recent report on food supply chains and the coronavirus pandemic found that prices at food and beverage retailers rose much faster than total cost over the course of the pandemic shock, suggesting some retailers were not simply raising prices to cover costs.

What is interesting about the Fed’s report is that while they rule out monopoly power as an explanation of inflation they point to firms anticipating cost increases as the source of inflation. This is noteworthy because inflation is typically blamed on workers, and for a similar reason. Traditional economics refers to a “wage-price spiral,” in which workers respond to cost of living increases by demanding higher wages, causing employer firms to raise prices leading to more inflation.

The recent reevaluation of inflation drivers from the Kansas City Fed suggests that firms squeezing their customers in this same way are doing so not to cover a real growth in payroll but rather a predicted spike in supply and shipping costs. This is a very different story about inflation than the one in most economics textbooks – a story of corporate greed and price gouging that snowballs from suppliers and logistics firms through to end users – and the new story has some interesting corroborations.

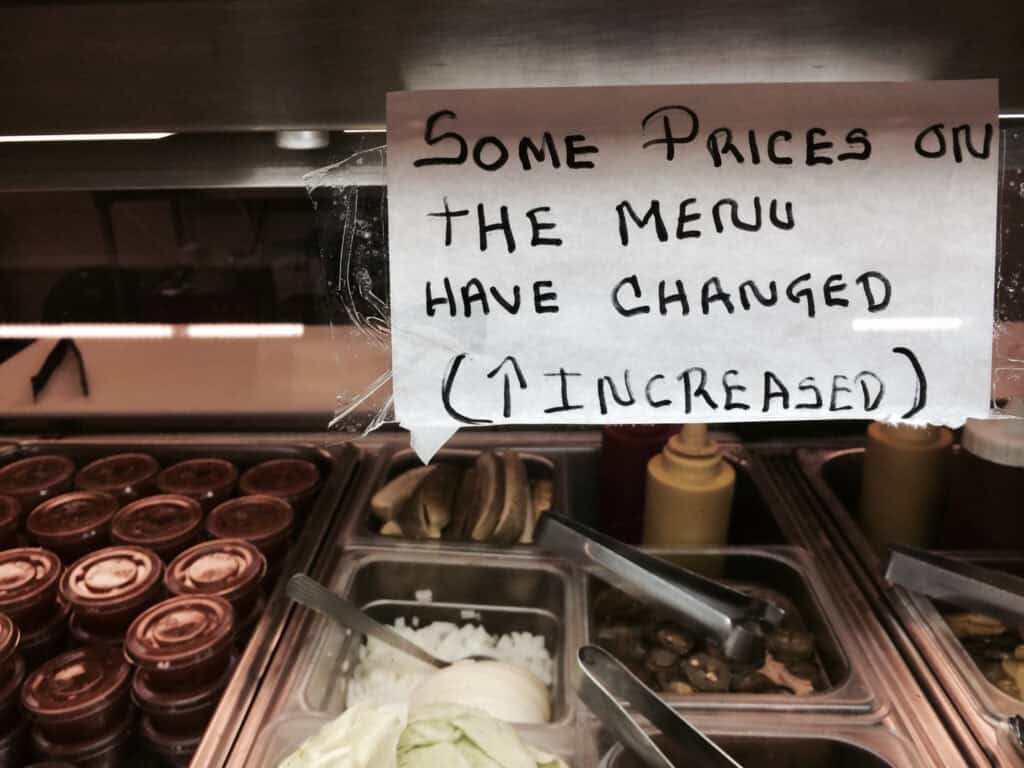

The phenomenon of ‘shrinkflation’, or when a company downsizes a product without downsizing the price, made rounds on social media before the New York Times and even the President gave legitimacy to the concerns of households. Food is one of the more visible components of inflation and thus many acts of shrinkflation were recorded in supermarkets and grocery stores. The FTC report details how large grocery retailers took advantage of their market power to engage in practices like shrinkflation to boost their profits at the expense of consumers and smaller retailers. The report hints at the decades of mergers and corporate concentration, leaving a food industry dominated by a very small number of corporations. Instead of competing for customers by containing prices or providing better goods and services, these conglomerates take almost the opposite approach: They compete for stock investors who shop around for higher profit margins rather than for families who shop around for the best deals to fit their tight budgets.

The cost of shelter is the largest component of the consumer price index, comprising roughly a third, and has consistently been a major contributor to monthly changes in inflation. Given the underlying data source it is highly likely the increases in shelter costs we are seeing now could be representative of price changes a year ago. Regardless, housing affordability remains the paramount issue on people's minds – and here, too, market concentration plays a role.

In October 2022, a lawsuit was filed against the company RealPage, a producer of software used to set rental prices. Tenants alleged that nine of the nation’s biggest property managers had conspired to inflate rents by forming a cartel. After backing from the Department of Justice, they were joined by similar suits that would be eventually consolidated into a sprawling class action lawsuit.

The sheer scale of the potential number of renters affected over the years could be in the millions. For example in the District of Columbia's suit against RealPage, the city’s 14 largest landlords listed as defendants own roughly 50,000 units alone. Given the racialized nature of rental burdens, RealPage and its gang of wealthy property owners probably disproportionately fleeced minorities and underserved communities and further entrenched the racial wealth gap and the homeownership gap.

RealPage is but one example of how market concentration can raise housing costs. The rapid rise in corporate landlords and the concentration in rental housing stock are another. While housing is and always will be a more diverse marketplace than the food industry used in the examples above, tools like RealPage facilitate the same end outcome: Instead of the virtuous competition traditional economics predicts, in which landlords fight each other to provide the best thing for the lowest price and the consumer benefits, a nefarious near-opposite pattern emerges.

The combination of housing unaffordability, inflation and a historically-strong-but-softening job market help explain the general economic pessimism weighing heavily on households.

Joseph Dean is NCRC's Racial Economic Junior Research Specialist.

Photo by atramos on Flickr.