Introduction

Under the Community Reinvestment Act (CRA) regulations, CRA examiners evaluate a bank’s record of responding to credit and banking needs in local communities in which it has branches. These areas are referred to as assessment areas (AAs). Over the years, industry stakeholders have sought to engage in community development financing in geographical areas outside of AAs. The agencies have responded by allowing banks to do so provided they have first met needs in their AAs.

Community development (CD) loans and investments are for affordable housing, economic development, revitalization of neighborhoods and community facilities. CD financing is distinguished from retail lending to homeowners and small business owners in that CD financing involves large-scale projects that have a community-wide benefit such as refurbishing a recreation center.

In order for neighborhoods to revitalize successfully, CD financing must work in tandem with retail lending. For example, loans to first-time homeowners will create sustainable neighborhoods with minimal residential turnover only if the homeowners reside in pleasant neighborhoods that feature ample access to stores and community facilities. Likewise, CD financing of economic development and neighborhood revitalization will be durable only if residents can obtain home or small business loans.

Because of this mutual dependence, CRA examiners must exercise care when deciding if banks have met CD financing needs in their AAs before they can engage in CD financing outside of their AAs in order to receive CRA credit. Over the years, industry stakeholders have commented that the process for determining when banks can offer CD financing outside of their AAs has been inconsistent and subjective.

In order to direct CD financing to areas of need, a thoughtful approach would ensure needs in AAs are addressed while also allowing banks to provide CD financing to underserved areas. The current CRA exam procedure allows banks to serve statewide or regional areas after satisfactorily serving needs in their AAs. NCRC, as described in more detail below, proposed numerical benchmarks as a means for increasing certainty in determining when a bank has met needs in its AAs. If a bank passed the numerical benchmarks, it could serve statewide and regional areas and also undeserved counties anywhere in the country.

In contrast, the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC) and Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) have offered a vague proposal for consideration of outside AA CD financing in their recent Notice of Proposed Rulemaking (NPRM).[1] It appears from the very few sentences in the NPRM describing this new approach, a bank could engage in an eligible CRA activity anywhere outside of its AA. Moreover, a large bank may need to pass its new CRA tests in only half of its AAs. Thus, under this proposal, it would be unlikely that examiners will carefully scrutinize retail lending and CD financing in AAs to ensure that they are effectively working in tandem. Moreover, it is unlikely that banks will target CD financing outside of AAs to areas most in need as measured by low levels of lending and high unemployment and/or poverty.

This white paper further developed the concept of underserved areas as counties that exhibit low levels of retail lending. It shows that allowing banks to serve underserved counties in areas outside of AAs would effectively target CD financing. Using data analysis and GIS mapping as a means of identifying underserved counties, NCRC developed a proposal for considering CD financing outside of AAs.

NCRC’s Proposal

In comments responding to the OCC’s Advanced Notice of Proposed Rulemaking in 2018, NCRC suggested that the agencies retain current procedures for qualifying CD financing outside AAs but further facilitate it by implementing annual data collection and increasing the number of eligible areas, called underserved areas.[2]

The NCRC proposal, further developed in a white paper in 2019, would work in the following manner:[3]

- The agencies would implement annual collection of CD data.

- Using this data, an examiner would determine one year after the previous CRA exam whether a bank is meeting needs in its AAs and could seek CRA CD financing outside of their AAs.

- The agencies would designate counties anywhere in the country as underserved in terms of CD lending and investing, and include them as options for outside AA CRA credit. These designations would be reevaluated every year.

- Banks would be able to conduct CD financing in the designated underserved areas in addition to CD financing statewide or in the region if the examiner deemed them eligible.

The annual collection of CD data would consist of data on lending and investing that would correspond to the CRA regulation categories defined as financing for affordable housing for LMI people, economic development geared towards supporting the creation and growth of small businesses, community facilities and other activities that revitalize and stabilize neighborhoods.[4] NCRC proposed that this data would be collected on a census tract and county level. Precedents for this data collection include OCC databases on public welfare investments that are produced every quarter and can be downloaded.[5]

Using CD data, an examiner can determine one year after the previous CRA exam whether a bank is meeting needs in its AAs. First, the examiner can determine whether for all AAs combined together, a bank is above or below median levels of CD financing for peer institutions. Then, the examiner can determine how current levels of CD financing in specific AAs compare to past levels on an annualized basis to see if a bank is on track to meet needs. If the bank passes these tests, the examiner can pre-qualify the bank as eligible to pursue CD financing outside of its AAs. However, if a bank does not pass muster on these measures, it can spend the next year improving its performance in its AAs and then ask for another agency review the second year after its exam. If the bank then passes the agency review, it could pursue community development outside of its AAs.

This procedure using CD data is more objective and certain than the current procedure, which appears to vary based on the subjective judgments of different CRA examiners. Also, it provides an opportunity for a bank not passing in the first year after its exam to improve during the second year and become eligible for outside AA CD activities.

In addition to retaining the allowance for outside AA financing in statewide and regional areas, NCRC suggested that the agencies also designate counties anywhere in the country that are considered underserved in terms of CD lending and investing. The agencies could develop measures to identify these counties such as the dollar amount of CD lending and investing on a per capita basis. Counties in the lowest quartile or quintile of CD financing per capita then could be candidates for designation as underserved.

The agencies could also use demographic and economic criteria for designating underserved areas much as they do now for identifying underserved and distressed rural, middle-income census tracts. A combination of lending, demographic and economic criteria could be used to designate underserved counties. The counties receiving underserved designation could be updated annually as in the case now with rural underserved and distressed tracts.

The designation of underserved counties would eliminate the possibility of cherry-picking counties that are easier places for banks to conduct CD financing outside of AAs. Hopefully, underserved county designation would alleviate the issue of hotspots and deserts by directing CD financing to places most in need. Also, since the designation of counties would be conducted annually, counties may come off the list if they received substantial amounts of CD financing and others may be added that have pressing needs. The annual designation may further smooth out and more evenly distribute CD financing.

As a further inducement for CD financing in underserved counties, the pre-qualification procedures could be less stringent for a bank to be allowed to engage. For example, a bank may need to be at or above median levels of CD financing to be eligible to engage in community development in a state or region, but could be below the median if it wanted to offer CD financing in underserved counties. Perhaps, the agencies could establish a tolerance such as no less than 20% below median for engaging in community development in underserved counties.

Underserved counties

To categorize counties as underserved, this analysis considered retail lending (home and small business lending). It did not consider CD financing since CD financing data was not available on a county level at the time the analysis was conducted. However, should the agencies implement county level CD data collection, it would be used in a manner similar to the retail lending described in this paper.

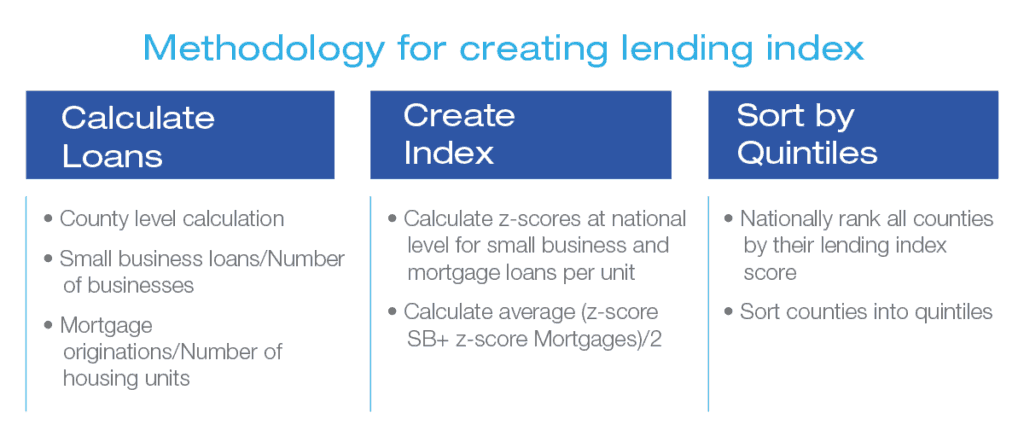

NCRC created a lending index by categorizing counties based on levels of lending activity. Specifically, NCRC calculated home loans per housing units and small business loans per operating businesses. The resulting values of mortgages and small business loans were then standardized at the county level utilizing z-scores. A simple average of z-scores combined the two measures in an index score for each county. NCRC then ranked counties by the combined lending index and sorted the counties into quintiles. NCRC used the most recent year for both the Home Mortgage Disclosure Act (HMDA) and CRA small business loan data, which was 2017 at the time of this analysis.

This diagram illustrates how we created the index:

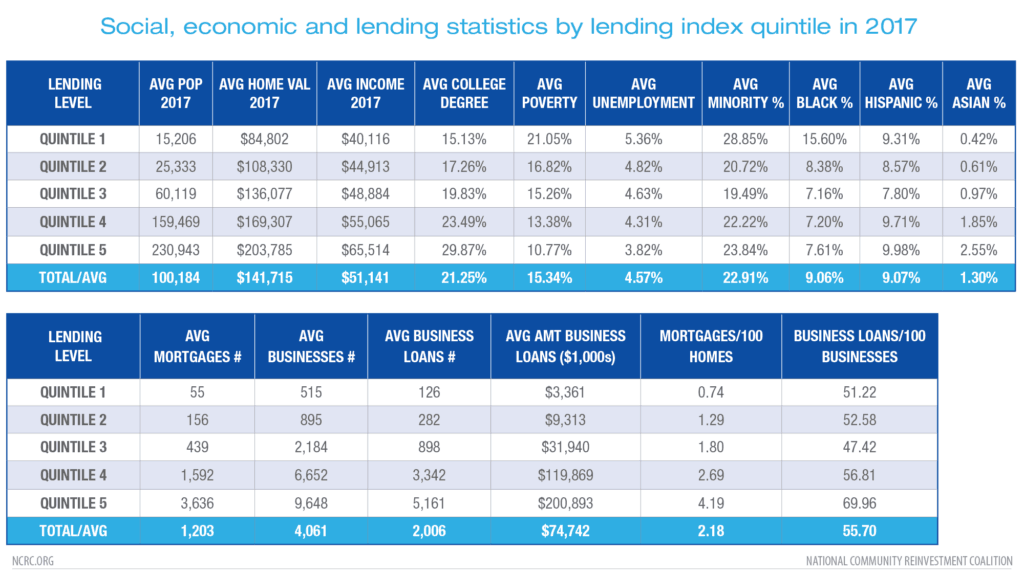

As shown by the accompanying table, counties in Quintile 1, the lowest quintile for retail lending, had an average of just .74 home loans per 100 homes. In contrast, Quintile 5, the counties with the highest level of retail lending, had an average of 4.19 home loans per 100 homes. A similar outcome occurred in the case of small business lending; counties in Quintile 1 had an average of 51.2 small business loans per 100 businesses in contrast to Quintile 5 that had almost 70 small business loans per 100 businesses.

The loans per business appear high because the CRA small business loan data includes data on credit card lending, which significantly increases the volume of lending. Credit card lending is higher cost than non-credit card lending and usually of much lower amounts, averaging $10,000 or less. Researchers do not have the ability to separate credit card from non-credit card lending from the CRA small business loan data. Hence, the loans per small business often appears high. Nevertheless, it still reveals significant differences in access to lending across groups of counties.

The most underserved counties were also those with the highest level of economic distress. Counties in Quintile 1 had an average poverty rate of 21% while counties in Quintile 4 and 5 had average poverty rates of 13.4% and 10.8%, respectively. Average unemployment rates were about 1.5 percentage points higher in Quintile 1 counties than Quintile 5 counties. Average income rates were also dramatically different; about $40,000 in Quintile 1 counties compared to $65,000 in Quintile 5 counties. Average home values were also more than twice as high in Quintile 5 counties than Quintile 1 counties.

Further sociological and demographic characteristics distinguished lower from upper quintiles. Counties in Quintile 1 had an average of 15% of the population with a college degree in contrast to almost 30% in Quintile 5. Counties in Quintile 1 had almost twice the average percentage of African Americans than counties in the other quintiles. In contrast, the percentage of Hispanics and Asians were similar across quintiles.

Another notable difference among quintiles was population levels. Counties in Quintile 1 had an average of 15,206 people and those in Quintile 2 had 25,333. In sharp contrast, counties in Quintile 5 had an average of 230,000 people. Over the years, the agencies have sought to focus on rural counties with lower levels of population when encouraging banks to serve underserved counties. NCRC’s proposed method of delineating counties by lending levels appears to achieve this outcome.

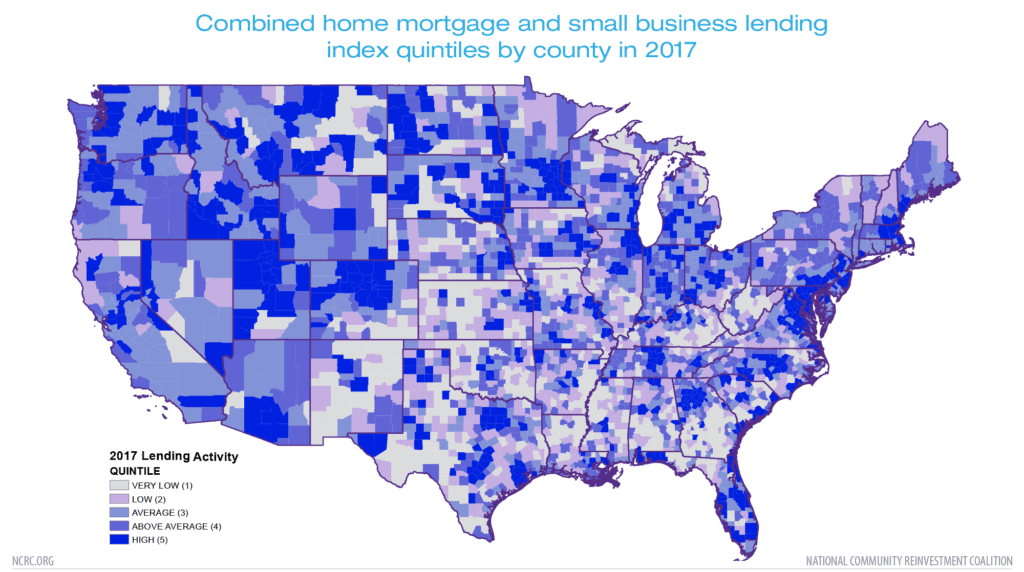

The accompanying maps clearly reveal that the Quintile 1 counties are disproportionately in the South, the Midwest and Appalachia, which include areas of economic distress and pressing needs.

Conclusion

NCRC would recommend designating Quintile 1 counties as underserved for purposes of considering outside of AA CD financing. Overall, Quintile 1 counties are the most distinct compared to the other quintiles in terms of higher levels of economic distress and lower population levels. Moreover, since the overall objective is to identify underserved counties, it would seem that the best measure is one that captures lending levels and reveals which geographical areas have the lowest lending levels.

NCRC’s proposal for consideration of CD financing outside of AAs was further developed than the FDIC’s and OCC’s. The NPRM did not present any data analysis to estimate the impact of the agencies’ cursory proposal. In contrast, NCRC’s proposal and analysis revealed how its designation of underserved counties would indeed target underserved counties, economically distressed counties, counties with higher levels of African Americans and most likely southern counties that have higher levels of poverty and unemployment.

In addition, NCRC’s proposal offered clear numerical benchmarks and procedures for qualifying banks for outside of AA CD financing. This ensures that reinvestment has a good chance of succeeding in AAs as well as providing reasonable opportunities to engage in CD financing outside of AAs and in areas of most need. In sum, NCRC’s proposal would be more successful in achieving CRA’s goals for responding to pressing community needs than the agencies.’

Appendix

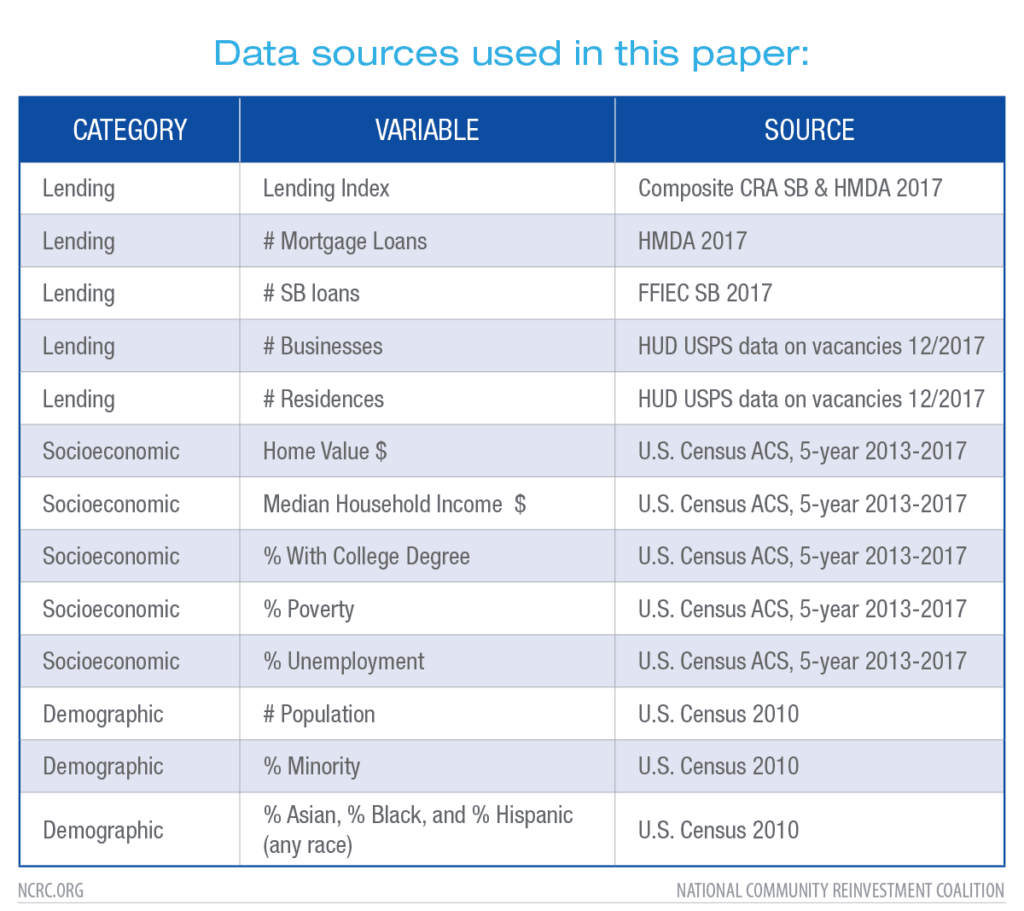

Data sources for this white paper are the following:

[1] Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC) and Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC), Joint Notice of Proposed Rulemaking (NPR), Community Reinvestment Act (CRA) regulations, Docket ID OCC-2018-0008 & RIN 3064-AF22, p. 44, https://www.occ.gov/news-issuances/federal-register/2019/nr-ia-2019-147-federal-register.pdf

[2] NCRC Comments Regarding Advance Notice Of Proposed Rulemaking (Docket ID OCC–2018-0008) Reforming The Community Reinvestment Act Regulatory Framework, https://ncrc.org/ncrc-comments-regarding-advance-notice-of-proposed-rulemaking-docket-id-occ-2018-0008-reforming-the-community-reinvestment-act-regulatory-framework/

[3] Josh Silver, An Evaluation Of Assessment Areas And Community Development Financing: Implications For CRA Reform, NCRC, July 30, 2019, https://ncrc.org/an-evaluation-of-assessment-areas-and-community-development-financing-implications-for-cra-reform/

[4] Definition of community development in the CRA regulations, see the Definitions section, §25.12, https://www.ffiec.gov/cra/regulation.htm

[5] To access the databases, see https://www.occ.gov/topics/community-affairs/resource-directories/public-welfare-investments/national-bank-public-welfare-investment-authority.html

Josh Silver, Senior Advisor, NCRC

Bruce Mitchell, PhD, Senior Analyst, Research & Evaluation, NCRC

Photo by Taylor Wilcox on Unsplash