Several affordable housing and civil rights organizations engaged in a multi-year advocacy campaign for expanding Massachusetts’ statewide Community Reinvestment Act (CRA) to include mortgage companies. The organizations thought a state level law was necessary for curbing abusive lending afflicting underserved communities. This report shows that CRA for mortgage companies succeeded in this objective as well as providing incentives for increasing responsible lending in traditionally underserved communities.

Executive Summary

Since 2007, Massachusetts has applied its Community Reinvestment Act (CRA) law to independent mortgage companies. Mortgage companies receiving a license to make loans in Massachusetts are examined and rated by the State’s Division of Banks (DOB). They undergo an exam that assesses their performance in making retail home loans to low- and moderate-income (LMI) borrowers and communities. The exam also scrutinizes and rates their community development services and investment activities.

This paper examines 50 CRA exams of mortgage companies, starting with the most recent year available, 2020, and going back to 2016. The objective is to describe how these exams assess mortgage company retail activities and community development initiatives in order to provide insights into how a federal law could be designed. The paper also assesses the objectivity and feasibility of CRA exams for mortgage companies.

The sample of CRA exams suggest that the ratings are based on objective criteria. A higher percentage of loans to LMI borrowers and communities are generally associated with higher ratings on the lending test. Likewise, more community development services and charitable donations result in higher ratings on the service test.

Overall, the Massachusetts experience indicates that applying CRA to mortgage companies is feasible and is likely to increase their retail lending and community development activity in LMI communities. The paper makes a series of recommendations for improving Massachusetts’ CRA exams for mortgage companies that should inform attempts to create a federal CRA for independent mortgage companies.

Background and Introduction

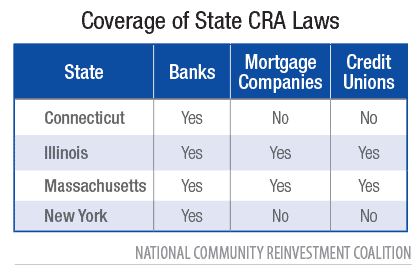

Massachusetts along with a handful of other states, including New York, Connecticut and recently Illinois, have adopted Community Reinvestment Act (CRA) laws to examine the performance of their state-chartered banks.[1] In addition to applying CRA to state-chartered banks, Massachusetts adopted it to credit unions and in 2007 to independent mortgage companies.[2] Massachusetts was a pioneer in CRA laws. As Congress was considering CRA in 1977, the banking commissioners of Massachusetts and Connecticut testified before Congress regarding the effectiveness of their early CRA efforts.[3]

Massachusetts’ CRA exams for mortgage companies (making 50 or more loans reported under the Home Mortgage Disclosure Act (HMDA)[4] contain a lending test, a service test and an optional investment test. The test awards one of five possible overall ratings: Outstanding, High Satisfactory, Satisfactory, Needs to Improve and Substantial Non-Compliance. The lending test and service test have the same five ratings. The DOB website does not describe the weights of the lending and service test (or points for each test) but it appears that the lending test carries the most weight based on how they are factored into the overall rating. A mortgage company cannot receive an overall rating of Satisfactory unless the company scores at least a Satisfactory on the Lending Test.[5] In contrast, a mortgage company can fail their service test and pass its exam. Several mortgage companies failed their service test with Needs to Improve ratings in NCRC’s sample and still passed their exam (see below).

Lending Test

The lending test has several components.[6] A significant part of the exam scrutinizes the distribution of home loans to LMI borrowers and census tracts. The number and percent of loans to LMI borrowers and communities are compared to demographic benchmarks (the percent of households that are LMI and percent of owner-occupied units in LMI tracts) and to industry benchmarks (the percent of loans made by all other lenders to LMI borrowers or tracts).

In addition the lending test has these additional sections:

Innovative or flexible lending products: the lender’s range of innovative and flexible home loan products, including offerings of government-insured loans or loans featuring low downpayment or other features designed to facilitate lending to LMI borrowers.

Loss mitigation efforts: the lender’s efforts to avoid borrower delinquency or foreclosure. The lender’s delinquency and foreclosure rates are compared to its peers. The lender’s efforts to offer loan modifications and other solutions to avoid delinquency and foreclosure are also assessed.

Loss of affordable housing: the mortgage company’s record of avoiding delinquency and foreclosure is assessed to ensure that there is no systematic pattern of loss of affordable housing.

Fair lending policies and practices: the company’s fair lending record is scrutinized to ensure that it is not discriminating. Discrimination or violations of consumer protection law can result in downgrades. Data on applications by race and ethnicity is assessed on this part of the test.

Service and optional investment test

The service test also has a number of components. The exam reviews the number of community development (CD) services which include homebuyer counseling, foreclosure prevention counseling or technical assistance to community-based organizations seeking to revitalize LMI communities. The exam looks at the range of delivery service mechanisms, including branches or online access. The service test also discusses donations that a company has made to nonprofit organizations involved in community development.

Lastly, mortgage companies have an optional investment test. If a mortgage company has at least a preliminary Satisfactory rating, it can try to obtain a higher rating by making qualified investments or community development loans.[7] Qualified investments and CD loans can finance affordable housing or efforts to revitalize and stabilize LMI tracts.[8] None of the mortgage lenders in NCRC’s sample opted for the investment test.

Assessment area

The assessment area for the mortgage company exams is the entire state of Massachusetts.[9] In other words, the exams assess lending and service performance for the mortgage companies in the state and base the rating on statewide performance.

Effect of CRA performance on applications

Massachusetts’ law hinges the approval of mortgage company applications in part on its CRA performance. In particular, the DOB considers CRA performance as a factor in applications to renew mortgage company licenses, the establishment or renewal of branches, and mergers with other mortgage lenders.[10]Unlike mortgage companies licensed in Massachusetts, banks under federal CRA regulations are not required to periodically seek approval for license renewals, contingent partly on CRA performance. The consideration of CRA performance in license renewals appears to be a novel aspect of Massachusetts’ regulation that could provide an added incentive for mortgage companies to comply with their CRA obligations.

Findings of NCRC’s Survey

As stated above, NCRC created a database containing the ratings and performance measures of 50 mortgage company exams. This survey does not cover all of the exams conducted by the DOB but contains a significant amount of them. Conducting a survey for the Massachusetts Affordable Housing Alliance (MAHA), researcher Jim Campen notes that his record of mortgage company ratings includes 74 exams. The distribution of ratings in his database did not differ substantially from NCRC’s sample, suggesting that adding more lenders to the NCRC survey would probably not change results meaningfully.[11]

Characteristics of the sample

The basic statistics of the sample are the following:

Sample year: Four exams were conducted in 2020, 17 in 2019, 12 in 2018, nine in 2017, eight in 2016.

Headquarters: All of the mortgage companies are required to be licensed by Massachusetts since they make loans in the state. Interestingly, however, the central headquarters of just nine companies are in Massachusetts while 42 are in other states.

Exam time period: The exams typically consider two years’ worth of loan and service data. For the lending test, two exams considered more than two years’ worth of data and just four exams considered one year worth of loan data.[12] For the service test, six exams considered more than two years’ worth of data and two exams considered one year’s worth of data. For unknown reasons, two exams did not contain service tests.

Massachusetts CRA exams are parsimonious and award relatively few high ratings

The state of Massachusetts has established a rating regime that awards fewer higher ratings and has a higher failure rate than the federal bank agencies. The comparison is inexact because the final ratings categories are different. Massachusetts’ exams have a High Satisfactory rating that the federal bank exams lack. The five possible overall and subtest ratings for Massachusetts CRA exams are Outstanding, High Satisfactory, Satisfactory, Needs to Improve and Substantial Noncompliance.

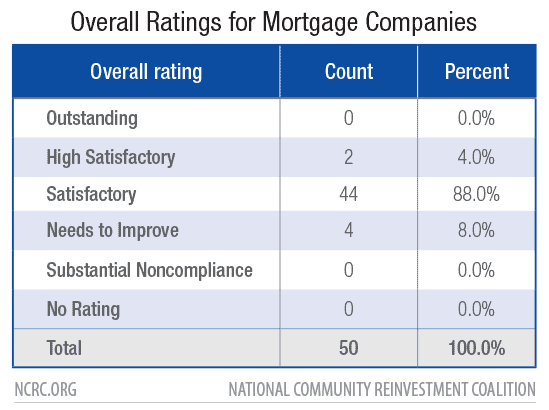

In the table below, the DOB did not award a single Outstanding rating to any of the 50 companies in NCRC’s sample. In contrast, about 10% of banks receive the Outstanding rating on federal CRA exams. It is conceivable that if Massachusetts did not have a High Satisfactory rating as a possible rating that some of the companies with High Satisfactory ratings may have received Outstanding ratings. Four percent of the mortgage companies received High Satisfactory. The great majority (88% or 44) earned Satisfactory ratings. Four or 8% of the exams gave companies the failed rating of Needs to Improve. However, one company failed twice so the actual number of companies failing in NCRC’s sample is three. In contrast, the failure rate is about 2% for federal bank exams.

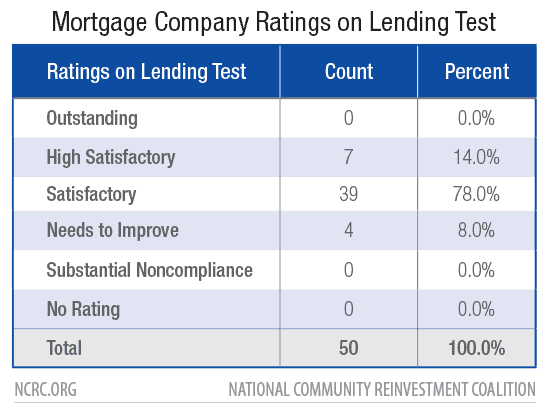

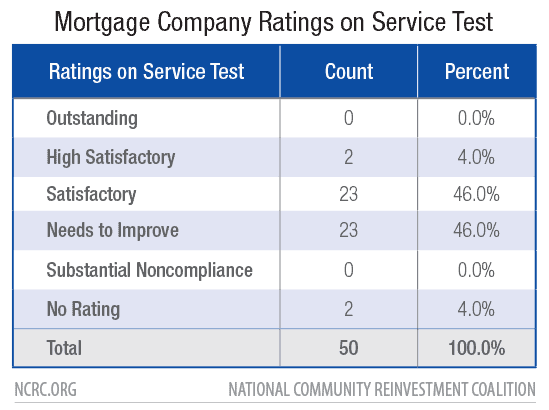

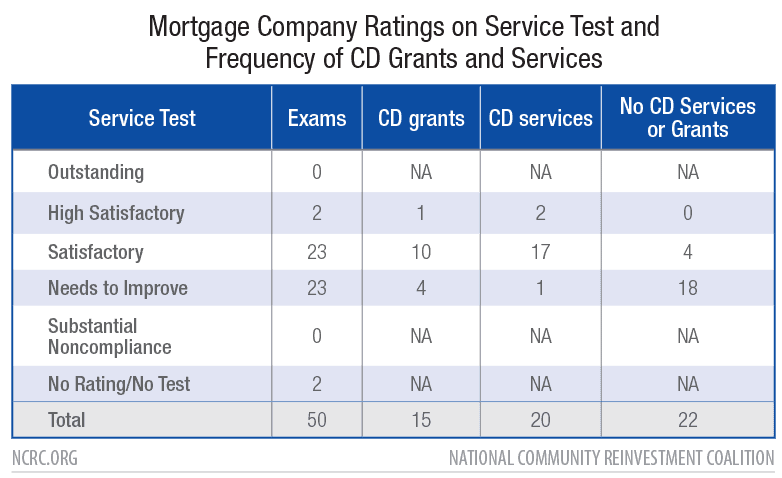

The service test has tougher ratings than the lending test but also counts for less in the overall rating. As stated above, the DOB’s regulations state that a mortgage company needs at least a Satisfactory rating on the Lending Test in order to pass overall. This does not apply to the Service Test. As shown below, almost half of the companies failed their Service Test, receiving Needs to Improve ratings. In contrast, just 4 or 8% of the exams recorded Needs to Improve ratings for the Lending Test.

Ratings on Lending Test Correspond with Performance

A critical question in reviewing the rigor and quality of CRA exams is to assess whether ratings correspond with actual performance. In other words, do mortgage companies that offer a higher percentage of their home loans to LMI borrowers and in LMI tracts have higher ratings. This analysis of NCRC’s sample suggests that Massachusetts’ CRA exams for mortgage companies pass this test and apply performance measures in an objective manner.

How the analysis was conducted

The CRA exams assessed retail lending performance in low-income and moderate-income census tracts separately. The exams also assessed performance to low- and moderate-income borrowers separately.

For each tract category and for the industry benchmark, NCRC calculated a percentage as follows using data from the CRA exams:

When expressed as a percentage, if the quotient is higher than 100% the mortgage company made a higher percentage of loans in the tract category than the industry as a whole. Conversely, if the quotient is less than 100%, the mortgage company made a lower percentage of loans in the tract category than the industry as a whole.

The tables below for borrowers use the same methodology except they substitute the percent of loans to a borrower category instead of the percent of loans to a tract category for the individual mortgage company compared to the industry.

For each tract category and for the demographic benchmark, NCRC calculated a percentage of as follows:

When expressed as a percentage, if the quotient is higher than 100%, the mortgage company made a higher percentage of loans than the percentage of owner-occupied housing units in the tract category. For example, if a mortgage company made 5% of its loans in low-income tracts and low-income tracts contained 3% of the owner-occupied units in the state of Massachusetts, the company would be offering a share of loans in low-income tracts that was 166% greater than the share of owner-occupied units in that tract category. Conversely, if the quotient is less than 100%, the mortgage company made a lower percentage of loans in the tract category than the share of owner-occupied units in the tract category.

NCRC conducted a similar analysis for borrowers below except that the demographic benchmarks for borrowers are the percent of families that are low- or moderate-income in the state of Massachusetts.

Results of the lending analysis

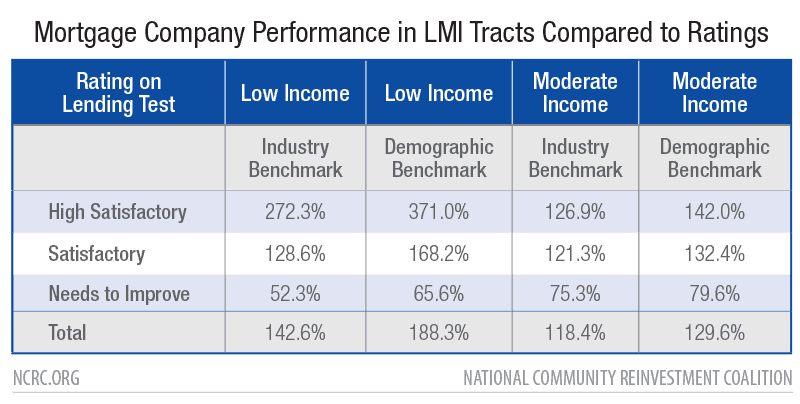

In general, mortgage companies with higher ratings had higher percentages including percentages considerably higher than 100% on the census tract performance measures. For example in Table 4, companies with High Satisfactory on the lending test had an average percentage of loans in low-income tracts that was 371% higher than the percentage of owner-occupied units in low-income tracts, compared to an average of 168.2% for companies with Satisfactory and 65.6% for companies with Needs to Improve ratings.

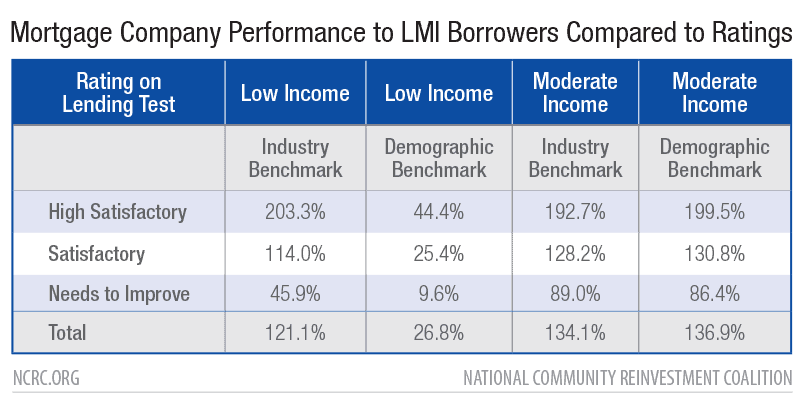

The same pattern occurs on the performance measures assessing lending to low-income or moderate-income borrowers. For instance in Table 5, when considering the percent of loans a company made compared to the rest of the industry, companies that scored High Satisfactory issued, on average, a 192.7% higher share of loans to moderate-income borrowers compared to 128.2% for those companies receiving Satisfactory ratings. In contrast, companies that received Needs to Improve ratings on the Lending Test had made on average of just 89% of the percentage of loans that all lenders issued to moderate-income borrowers.

Percent of Applications Received from People of Color Do Not Correspond to Ratings on Lending Test

Massachusetts’ CRA exams also contain a fair lending test that ensures that companies are not discriminating against people of color. The test contains tables that assess the percent of applications received by racial minorities (African-Americans, Hawaiians/Pacific Islanders, Native Americans) and ethnic minorities (Hispanics). The fair lending analysis conducted by Massachusetts CRA examiners used applications submitted by borrowers in contrast to loan originations for LMI tracts and borrowers discussed above.

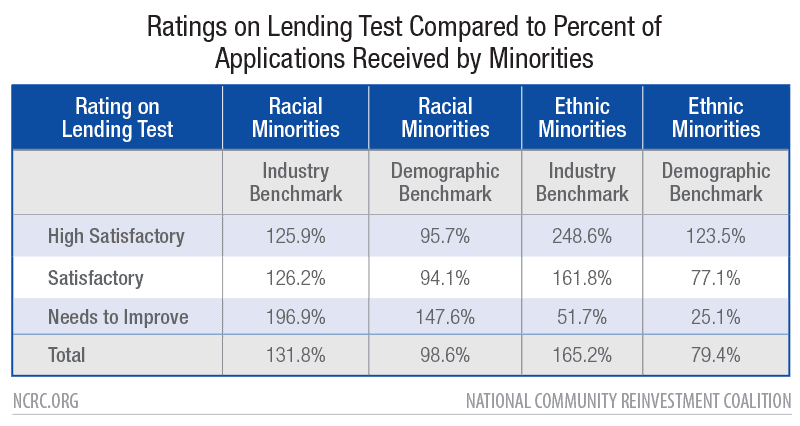

Table 6 showed that companies in the High Satisfactory and Satisfactory rating categories perform about the same on the industry and the demographic benchmarks for racial minorities (this benchmark compared a company’s percentage of applications to the percentage of the population that were racial minorities in a manner similar to that discussed above for LMI borrowers). Those with Needs to Improve ratings actually perform better on these benchmarks, on average. In contrast, higher averages on the benchmarks for ethnic minorities corresponded to higher ratings

The differences found in the income compared to the racial performance measures suggests that the racial indicators may not have as much impact on the final rating. Perhaps, as long as the DOB does not find that a mortgage company discriminated on the basis of race or ethnicity, it is likely to pass its fair lending review even if it received a relatively low percentage of applications from racial minorities.

NCRC’s sample of 50 companies revealed that only one was downgraded, but not for evidence of discrimination but due to a “number of significant credit violations” of consumer protection laws.[13]

Other Criteria on the Lending Test

As discussed above, the lending test includes additional criteria including innovative or flexible lending practices, loss mitigation efforts and loss of affordable housing. The exams included in this study tend to contain generic descriptions of findings under these criteria that are not informative in guiding the reader to understand how these criteria contributed to the ratings.

On the criterion of innovative and flexible, the exam typically describes an inventory of government-insured loans, Fannie Mae or Freddie Mac products or Massachusetts Housing Finance Agency products that a lender offers. The exam does not offer insights into whether these products helped the lender increase their number or percentage of LMI or people of color borrowers. The reader would have to conduct a close examination of different exams to make these determinations.

A comparison of two exams (one in which a lender scored High Satisfactory on the lending test and the other scored Satisfactory) reveals that the lender with the higher rating on the lending test had a higher percentage of government-insured loans issued to LMI borrowers and communities.[14] However, this finding by itself would not be a conclusive reason why one lender had more success in reaching LMI borrowers unless the exam also discussed the percentage of government-insured loans in the lender’s portfolio.

The final two criteria were loss of affordable housing and loss mitigation. It is unclear why these two criteria are not combined into one since both of these examine delinquency and default rates and assess whether these rates were above, at or below industry averages and whether these rates lead to a loss of affordable housing. The discussions in the exams were perfunctory and did not indicate how or if these criteria contributed to the overall ratings. As far as the reader could discern, all the mortgage companies had acceptable loss mitigation strategies and results, with no loss of affordable housing. Refinement in these criteria should identify differences in performance in this area since it is unlikely that the 50 exams in NCRC’s sample had companies performing in the same manner on these criteria.

Service Test

As discussed above, the service test examines the amount of community development (CD) services and grants and also examines mortgage service delivery such as lending through branches, through brokers or the internet. The exams do not seem to rate performance based on service delivery since the exam narrative usually just notes whether lenders deliver services through branches or non-branch means. Eleven out of 50 exams noted the presence of physical branches. The mortgage company with the highest number of branches in LMI tracts had nine in these tracts.[15]

Not surprisingly as shown in Table 7, lenders that offered CD services and grants had higher ratings on the service test than those that did not. Two lenders had High Satisfactory on the service test; both of these offered CD services like homebuyer or homeownership counseling and one of them provided CD grants. Of the 23 mortgage companies earning a Satisfactory rating on the service test, 17 offered CD services and 10 provided CD grants. Of the 23 companies receiving a Needs to Improve rating, 18 did not offer either CD grants or services. Four of them provided CD grants and one provided a CD service. Finally, exams were not consistent in indicating whether or not a company offered CD services or grants.

Exams seemed to differentiate performance based on the number of CD services and the dollar amount of grants. For example, one lender that had a high Satisfactory on the Service Test offered 30 homebuyer sessions and one-on-one counseling in 30 minute sessions.[16] This lender also made $32,000 in donations to organizations that provide community development services and affordable housing. In contrast, organizations that received Satisfactory on the Service Test typically made donations under $10,000 or offered approximately 10 to 15 homebuyer seminars.

Optional Investment Test

As discussed above, the optional investment test is available for mortgage companies that have scored at least a Satisfactory rating and seek to improve their performance. The test would consider either CD loans or investments. No mortgage companies included in NCRC’s survey opted for the investment test.

Two of the mortgage companies in NCRC’s survey have made multifamily loans as revealed by the Home Mortgage Disclosure Act (HMDA) data. Federal CRA exams for banks consider multifamily loans (permanent financing or construction loans) to be CD loans.[17] It is unclear why these two mortgage companies did not seek bonus points under the optional investment test by qualifying their multifamily loans as CD loans. Perhaps, they did not make multifamily loans in Massachusetts during their CRA exam cycle, or their multifamily lending activity in general is low volume or they were content with their ratings and did not seek to boost them.[18]

The overall question is whether the optional nature of the investment test results in communities in Massachusetts missing community development financing opportunities such as permanent financing or construction lending for multifamily lending. While mortgage companies are engaged in this type of financing, it is possible that the companies licensed in Massachusetts are not large players in this financing. Nevertheless, a modest restructuring of the component tests might leverage more community development financing as described immediately below.

Recommendations

This paper analyzed Massachusetts’ CRA law as applied to mortgage companies. It shows overall that the law and its implementing regulations have been effective in assessing mortgage company CRA performance in a feasible manner that recognizes differences in performance, particularly on the lending test. However, the performance measures could use some refinement in order to further motivate mortgage companies to improve their CRA performance. In addition, stakeholders have considered whether CRA should be applied to mortgage companies on a federal level. Below, this paper offers recommendations for the state of Massachusetts and for policymakers on a federal level considering CRA for mortgage companies.

Recommendations for the state of Massachusetts

- The state should more fully utilize its five ratings for mortgage companies – As described above, Massachusetts’s CRA has five possible overall ratings. NCRC’s survey found that none of the 50 exams analyzed awarded an Outstanding rating or a Substantial Noncompliance rating and that 88% of the exams awarded a Satisfactory rating. It is unlikely that performance is accurately revealed by such a large percentage of companies receiving one rating. More companies should have probably received the highest two ratings as well as more failing their exams.

- Performance ranges should be established for revealing more distinctions in performance on the lending test – The Federal Reserve Board (Board) in their Advance Notice of Proposed Rulemaking (ANPR) on reform of federal CRA ratings proposed performance ranges for the quantitative measures to assign ratings to various levels of performance. For example, as discussed above, the average percent of loans to LMI borrowers was higher for companies receiving High Satisfactory as opposed to Satisfactory ratings on the lending test. Ranges could be assigned to different ratings; the ranges would capture the extent to which a particular company exceeded or fell below the industry or demographic benchmarks discussed above. For example, on the industry benchmark for percent of loans in moderate-income tracts, the range for Outstanding could be 150% and higher above the industry benchmark. The ranges would be developed based on an analysis of performance over a number of years, using data from CRA exams in a manner similar to this analysis. The discussion above also describes how other parts of the lending test could further develop quantitative measures for the other criteria of the lending test such as innovation and flexibility.

- The criteria on innovation and flexibility in the lending test could provide more insights into performance if consistent quantitative comparisons are offered – Exams discussed innovative and flexible loans such as government-insured loans but did not clearly indicate how these loans impacted performance. Consistent metrics for these loans such as the percentages of these loans for LMI borrowers and people of color and the percent of these loans as a portion of the lender’s portfolio would help a reader understand if flexible loan products bolstered a lender’s performance.

- The fair lending test should develop performance ranges – As discussed above, ratings did not correlate as well with percentages of applications received by people of color as they did with the percentages of loans made to LMI borrowers or communities. To improve the correspondence between ratings and the percentages of applications received by people of color, the fair lending section of the lending test should develop performance ranges. A lender’s score on performance ranges used on the fair lending section should contribute to the overall rating on the lending test. This would improve consistency and objectivity of the lending test.[19]

- Descriptions of the testing for discrimination and violations of consumer protection laws should be provided – The DOB CRA exams should have additional discussion about how they tested for discrimination, including a description of the methodology used such as econometrics or matched-pair testing and what products were tested. In addition, when violations of consumer protection law are found such as in the case discussed above, the exams should provide more detail about in which products the violations occurred and what corrective actions the lender took so as to avoid these violations in the future.[20]

- The lending and service tests should develop weights for the various criteria – The lending test has a number of criteria including the percent of loans to LMI borrowers, LMI tracts, innovation and flexibility and criteria under the fair lending test. The service test likewise has various criteria. The DOB should develop weights for each of these criteria and explain how performance under these criteria contribute to the overall rating.

- Quantitative benchmarks should be established for the service test – As stated above, the lenders performing best on the service test seemed to be offering or participating in one or two homebuyer seminars/counseling sessions per month over a two year time period. The DOB should establish a benchmark along these lines for lenders to aim for the highest ratings on the service test. Some tailoring and adjustment for various business models is appropriate to take into consideration the number of staff mortgage companies have in the state compared to the extent of their online activity. Likewise for donations with a community development purpose, benchmarks or performance ranges should be established based on analysis of historical data in CRA exams (these benchmarks and ranges should be updated every two or three years as new exams are conducted).

- The DOB should conduct research to size the market for CD lending and investing – NCRC’s analysis suggests that relatively few mortgage companies chartered in Massachusetts offered multifamily loans. However, this may change in the future since many of these companies are regional or even national in scope. DOB should either conduct or commission research sizing the market for mortgage company CD lending and investing. This research would then inform DOB regarding whether it should retain or reform its exam structure, particularly regarding the optional investment test. If mortgage companies conduct sizable amounts of CD loans and investments, the DOB may want to consider the creation of a separate CD financing test.

- Qualitative scores should be developed for the tests – The DOB should develop qualitative scores for at least some of the test criteria such as innovation and flexibility on the lending test or CD services section of the service test. The qualitative criteria could consist of a scale of 1 to 5 and assess the extent to which the activities were responsive to need and successfully reached underserved populations. For example, if a mortgage company offered high volumes of loans that had safe and sound and innovative features like low down payments or the use of alternative creditworthiness factors that facilitated lending to underserved populations, it would have a higher qualitative score. Likewise, if the CD services efforts of the companies had impact data such as how many clients of one-on-one counseling sessions improved their credit records, the company would have a higher qualitative score. The DOB can encourage companies to collect data (in collaboration with nonprofit and public sector partners when appropriate) on the impact of CD services. The qualitative scores could be weighted at a certain percentage of the lending or service test such as 20% to 30%.

- Assessment areas should include metropolitan and rural counties as well as the state – As discussed above, the DOB designates the state of Massachusetts as the single assessment area for the mortgage companies. The upside of this approach is simplicity; the exam’s lending and service tests analyzed performance in just one geographical area. However, the mortgage companies in NCRC’s sample most likely had various concentrations of lending activity, with some that may have been more urban-based while others may have had a larger presence in rural areas. NCRC has developed an approach for branchless lenders and hybrid lenders (both branches and non-branch service delivery) that focuses on underserved areas as well as including a mix of more densely populated urban metropolitan areas as well as smaller areas. The emphasis on a diversity of areas is to ensure that lenders are making consistent efforts to serve urban and rural areas so that smaller urban and rural areas do not experience less access to credit, which is a recurring disparity in the current lending marketplace.[21] The DOB should consider adding a few assessment areas representing a mix of large and small urban areas and rural areas for the exams.

Recommendations for a federal CRA or duty to serve for mortgage companies

- A federal law would increase the effectiveness of state CRA laws for mortgage companies – On a federal level, Senator Elizabeth Warren (D-MA) and Representative Emanuel Cleaver (D-MO) have introduced the American Housing and Economic Mobility Act (S. 1368, H.R. 2768) that would strengthen CRA as applied to banks and would extend CRA obligations to independent mortgage companies.[22] Under this proposal, mortgage companies would have a lending and community development test. The bill was inspired by the Massachusetts CRA law and borrowed many of the components of the law described above. It could enhance state laws since a mortgage company licensed by several states would need to adhere to a federal CRA law in addition to Massachusetts and any other state law that included mortgage companies (Illinois just adopted such a CRA law).

- Assessment areas must include local areas: As stated above, the Massachusetts CRA regulation for mortgage companies designates the state of Massachusetts as the assessment area for mortgage company CRA exams. At a minimum, any future federal CRA exams for mortgage companies should assess lending on a state level. However, assessment areas should include a diversity of larger and smaller urban areas as well as rural counties to make sure mortgage companies are serving differing and unique local needs. NCRC has developed an approach that is feasible and replicable for designating assessment areas that also capture underserved areas.

- CRA ratings must be nuanced and reflect distinctions in performance – The Massachusetts CRA regulation includes five possible ratings, which is an improvement over the federal ratings scheme of four ratings. Five ratings provides the possibility of revealing more distinctions in performance. The shortcoming has been implementation; DOB did not fully utilize the five ratings as exemplified by no lender in NCRC’s sample receiving an Outstanding or Substantial Noncompliance rating. The recommendations above for improving the quantitative and qualitative performance measures for the exam components including the fair lending review would also help in the case of a federal CRA for mortgage companies. In addition, NCRC has recommended that federal exams for banks also have five overall ratings and/or a point system to provide more distinctions to the current four ratings system.

- Exam components on a federal level should be developed after a baseline study is completed – The Massachusetts’ regulation designates a lending and service test. Any federal requirement might want to consider substituting a community development test for the service test. A community development test would assess community development services such as housing counseling which mortgage companies have expertise for deliversing and funding. A baseline study would also establish whether mortgage companies have regular and sizable capacities for community development financing particularly related to rental affordable housing. If so, a community development financing subtest would be desirable.

- CRA performance must be factored into applications submitted by mortgage companies – The Massachusetts DOB considers CRA performance when a mortgage company has submitted an application for approval, including applications for license renewals. This consideration of CRA performance provides an incentive for mortgage companies to pass their CRA exams. This feature must be a part of any future federal law, and is part of the Warren and Cleaver bill.

Conclusion

This paper analyzed CRA exams of mortgage companies in the state of Massachusetts in order to better understand how CRA exams of mortgage companies operate and assess mortgage company performance. The paper demonstrated the feasibility of this type of examination since the Massachusetts’ DOB has been conducting these exams for a number of years. Moreover, the criteria on the component tests are objective and the companies know what to expect in terms of how they will be evaluated. As with all endeavors, the exams can be improved and NCRC has offered a number of suggestions based on its own experience as well as the CRA regulatory reform ideas that have been proposed by the Federal Reserve Board. Overall, since the Massachusetts exams award higher ratings for better performance, they appear to be effective in motivating improvements in CRA performance.

Massachusetts as well as a few other states have CRA laws.[23] Massachusetts and the new Illinois law recognize that a CRA obligation should be broadly applied to various types of lenders in order to best promote uniform and improving reinvestment performance.

Methodological notes

This study examined 50 CRA exams of mortgage companies conducted by the Massachusetts DOB using exams conducted and released during 2020 through 2016. NCRC chose the most recent years for which exams were available at the time of the study because NCRC wanted to focus on the most current DOB CRA exam practices, which might have changed from those in earlier years.

For the criteria on the lending test, the NCRC survey used the most recent year for which HMDA data was available for the individual company and the industry aggregate.

Appendix

Table 8[24]

Table 8[24]

[1] NCRC has been able to identify CRA laws in the following states in addition to Massachusetts: New York, Connecticut and the recently passed law in Illinois. See the following websites for these laws: Massachusetts Division of Banks, Community Reinvestment Act (CRA) for banks and credit unions, https://www.mass.gov/info-details/community-reinvestment-act-cra-for-banks-and-credit-unions, New York State Department of Financial Services, The Community Reinvestment Act,, https://www.dfs.ny.gov/apps_and_licensing/banks_and_trusts/about_cra and https://www.dfs.ny.gov/reports_and_publications/exam_reports, State of Connecticut Department of Banking, Community Reinvestment Act Ratings, https://portal.ct.gov/DOB/Bank-Data/CRA/CT-Bank-Ratings. The Illinois CRA bill became law in early 2021 so no regulations have been developed yet. A press release about the law can be viewed here, Illinois Department of Financial and Professional Regulation, DFPR Announces Webinar on Historic Implementation Process of Illinois’ Community Reinvestment Act, May 28, 2021 https://www.idfpr.com/News/2021/2021%2003%2023%20Predatory%20Loan%20Prevention%20and%20CRA.pdf. Also see, https://www.idfpr.com/News/2021/2021%2005%2028%20CRA%20discussion%20press%20release.pdf

[2] Massachusetts CRA exams for banks, credit unions and mortgage companies can be viewed here: https://www.mass.gov/archive/community-reinvestment-act-compliance

[3] Josh Silver, The Purpose And Design Of The Community Reinvestment Act (CRA): An Examination Of The 1977 Hearings And Passage Of The CRA, NCRC, June 2019, https://ncrc.org/the-purpose-and-design-of-the-community-reinvestment-act-cra-an-examination-of-the-1977-hearings-and-passage-of-the-cra/

[4] Massachusetts DOB regulations, 209 CMR 54.00: Mortgage lender community investment, see defintions section, 54.12, https://www.mass.gov/regulations/209-CMR-5400-mortgage-lender-community-investment#54-12-definitions

[5] See section 54.24 (assigned ratings) of the DOB’s regulation, https://www.mass.gov/regulations/209-CMR-5400-mortgage-lender-community-investment#54-11-purposes-and-scope

[6] Massachusetts DOB, Self-Assessment Guide to CRA (Community Investment) for Mortgage Lenders, January 2017, https://www.mass.gov/doc/self-assessment-guide-to-cra-for-mortgage-lenders/download

[7] DOB, Self-Assessment Guide for Mortgage Lenders, https://www.mass.gov/doc/self-assessment-guide-to-cra-for-mortgage-lenders/download

[8] See Massachusetts DOB regulations, Section 54.12: Definitions, https://www.mass.gov/regulations/209-CMR-5400-mortgage-lender-community-investment#54-11-purposes-and-scope

[9] Massachusetts DOB, Mortgage Lender Community Investment (CRA for mortgage lender): Assessment Area, https://www.mass.gov/info-details/mortgage-lender-community-investment-cra-for-mortgage-lenders#examination-process-

[10] See Massachusetts’ DOB regulation, Section 54.26: Effect of record of performance on applications, https://www.mass.gov/regulations/209-CMR-5400-mortgage-lender-community-investment#54-11-purposes-and-scope

[11] Jim Campen, CRA ratings of Massachusetts Banks, Credit Unions, and Licensed Mortgage Lenders in 2020, MAHA’s Thirtieth Annual Report on How Well Lenders and Regulators Are Meeting Their Obligations Under the Community Reinvestment Act, January 2021, https://mahahome.org/sites/MAHA-PR1/files/CRA Ratings 2020.pdf. Mr. Campen reported that of the 74 mortgage companies that have received rartings as of end of year 2020, 4 or 5.4% had High Satisfactory, 65 or 87.8% had Satisfatory, and 5 or 6.8% had Needs to Improve. The Massachusetts CRA website as of June 8 2021 when NCRC research concluded did not have any 2021 CRA exams for mortgage companies.

[12] For exams in future years, the number of years of loan and service data could be related to less frequent exams for mortgage companies receiving High Satisactory or Oustanding ratings. A regulatory bulletin (1.3-105 Alternative CRA Examination Procedures) provides the Massachusetts DOB with discretion to conduct exams less frequently than once every 24 months for institutions that have High Satisfactory or Outstanding ratings. The time period could range from once every 36 months to 60 months. Less frequent exams could entail using more years of data than the two years of data associated with most exams conducted every two years in the NCRC survey. See https://www.mass.gov/regulatory-bulletin/13-105-alternative-cra-examination-procedures

[13] See the Massachusetts CRA exam, https://www.mass.gov/doc/milend-inc-cra-public-evaluation/download?_ga=2.39343907.1075561394.1538660733-51556280.1538585926

[14] The two lenders compared had these Massachusetts CRA exams: https://www.mass.gov/doc/equity-prime-mortgage-llc-mlci-public-evaluation/download and https://www.mass.gov/doc/conway-financial-services-llc-mlci-public-evaluation/download. Also, Massachusetts CRA exams consider all types of government-insurred loans including those guaranteed by the Department of Housing and Urban Development, the Veterans Administration and the United States Department of Agriculture. The exams also consider loans companies offer via Government-Sponsored Enterprise programs and those of the state housing finance agency.

[15] See the following Massachusetts CRA exam: https://www.mass.gov/doc/fairway-independent-mortgage-corporation-mlci-public-evaluation-0/download

[16] See the following Massachusetts CRA exam: https://www.mass.gov/files/documents/2018/05/01/mortgagenetwork-pe.pdf

[17] Office of the Comptroller of the Currency, Federal Reserve System, Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, Interagency Questions and Answers regarding the Community Reinvestment Act, Federal Register, Vol. 81, No. 142, Monday, July 25, 2016, Section .12(h), p. 48528.

[18] These are the two Massachusetts CRA exams for lenders that made some multifamily loans as shown by the publicly available HMDA data. Their websites did not highlight multifamily lending. https://www.mass.gov/doc/primelending-a-plainscapital-company-mlci-public-evaluation/download and https://www.mass.gov/doc/broker-solutions-inc-mlci-public-evaluation/download

[19] For a perspective about how guidelines can help improve consistency in evaluations and judgements, see Daniel Kahneman, Olivier Sibony and Cass R. Sunstein, Bias Is a Big Problem. But So Is ‘Noise,’ Guest Essay in the New York Times, May 15, 2021, https://www.nytimes.com/2021/05/15/opinion/noise-bias-kahneman.html

[20] Federal CRA exams of banks do not describe the methodologies they employed although they did in the 1990s (see NCRC comment on the OCC Advanced Notice of Proposed Rulemaking, November 2018 via https://ncrc.org/ncrc-comments-regarding-advance-notice-of-proposed-rulemaking-docket-id-occ-2018-0008-reforming-the-community-reinvestment-act-regulatory-framework/). When violations occur, the exams discuss fair lending or consumer protection laws that were violated as well as the products involved.

[21] Josh Silver, How Can Geographical Areas On CRA Exams Work For Branchless Banks?, NCRC, January 2021, https://ncrc.org/how-can-geographical-areas-on-cra-exams-work-for-branchless-banks/

[22] NCRC Summary Of The Section 203, Strengthening The Community Reinvestment Act Of 1977, of the American Housing And Economic Mobility Act Of 2021 (S. 1368, H.R. 2768), https://ncrc.org/ncrc-summary-of-the-section-203-strengthening-the-community-reinvestment-act-of-1977-of-the-american-housing-and-economic-mobility-act-of-2021/

[23] See above.

[24] See above.

Featured image: ©Jo Panuwat D