This is one in a series of racial wealth snapshots. See more here.

The United States has too often hindered Native American advancement, not advanced it. Through years of intentional governmental policies that removed lands and resources, American Indians have been separated from the wealth and assets that were rightfully theirs. Today, we still see a lack of information on Native Americans and their socioeconomic issues. Data is sparse and inconsistent. This report pulls together the best and most current information we could find. However, it is still incomplete. Native Americans continue to be disenfranchised through a racial wealth divide like Latinos and African Americans. Yet despite this ongoing inequality, it is also true that Native Americans have made socioeconomic progress. Native Americans have seen decreased poverty and unemployment rates, and increased income and educational attainment over the last 25 years.[1]

Demographics & Civil/Tribal Rights

The Native American population has grown exponentially throughout the years. According to US Census data in 2020, there were roughly 6.79 million Native Americans throughout the country. Therefore, this community only accounts for a mere 2.09% of the total population across all races and ethnicities. Along with a growing population, there has been an increase in civil and tribal rights. Thanks to legislation such as the Indian Self-Determination and Education Assistance Act of 1975, the Tribal Self-Governance Act of 1994 and generations of advocacy, Native American communities have greater control over their own land and resources and have experienced an increase in federal recognition of their tribal governments. According to a HUD report on Native American housing conditions, one-third of the American Indian or Alaska Native (AI/AN) population lives on reservations, with another 26% living in counties surrounding tribal areas.

According to the 2010 US Census data, roughly seven of 10 American Indians reside in an urban area. The cities with the highest concentration of Native Americans are New York, Los Angeles, Phoenix, Oklahoma City and Anchorage. As of 2020, Alaska is the state with the highest percentage of Native Americans with 20.32%. Oklahoma, New Mexico and South Dakota all follow with 13.19%, 10.75% and 10.09%, respectively. While Native Americans represent only 1.93% of California, it has the highest volume of Native American residents with a total of 762,733. Oklahoma has the second largest number of Native American residents. Native Americans account for 526,408 inhabitants. Arizona has the third highest concentration, where there are 399,151, or 5.31% of the total population. The Native American demographic is a diverse population. Some live in urban areas, others rural, and there are varied racial makeups, with some who are card-carrying members of recognized tribes and many others who are not. Yet throughout most Native American communities, racial economic inequality is a consistent characteristic.

Wealth

Wealth is different from income – it is the total value of assets, minus debts. Unfortunately, Native American wealth data is not available from the US government. There is so little data on Native American wealth we have to source data from 2000 highlighted in Mariko Chang’s seminal paper, “Lifting As We Climb: Women of Color, Wealth, and America’s Future,” where it sites an estimate of a median $5,700 for Native American wealth compared to a median $65,000 of wealth for the American population as a whole.

This data has Native American wealth at about 9% of the national average. The National Longitudinal Survey of Youth 1979 (NLSY79) surveyed the wealth of respondents, who were to identify as one of three groups: Non-Black/Non-Hispanic, Black, or Hispanic/Latino. Regardless of identity, all three of these groups saw a gradual increase (though disproportionate amongst these groups as well) in wealth accumulation over time, whereas according to Chang’s report, Native Americans did not, and consequently they have such a low share of wealth compared to the national median.

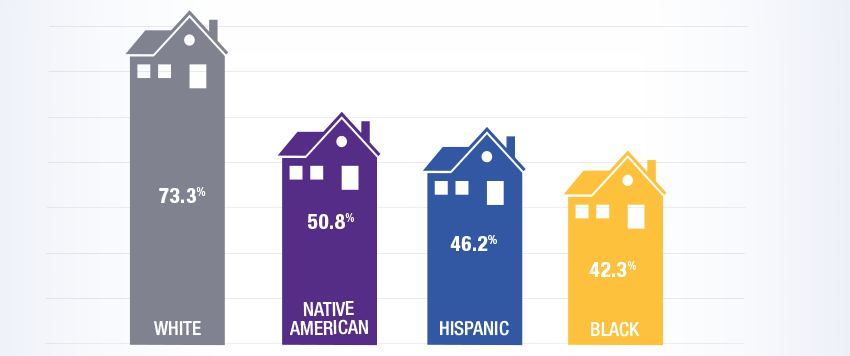

Homeownership

According to the US Census Bureau, homeownership rates for Native Americans in 2017 were at 50.8%. Although Native American homeownership rates are higher than those of Black and Latino populations, it is still substantially lower than the non-Hispanic White homeownership rate of 72.3%. Another concerning factor is that Native American homeownership is at one of the lowest rates it’s been since 1994, when it was at 51.7%. Homeownership rates were steadily increasing, reaching a high of 58.2% in 2005 and 2006, then decreased to a low of 47.6% in 2016. According to a HUD report on Native American housing conditions, Native American homeownership was 47% for counties surrounding tribal lands and other metropolitan areas in 2010. However, it was considerably higher in tribal-owned areas at 67% in 2010, which could account for their higher homeownership rates compared to other minorities. However, the median home value for AI/AN people is $135,200. This is only two-thirds of the median home value for White people at $219,600. It is also important to note that even with these higher rates, Native Americans in larger tribal areas are most likely to experience overcrowding and inadequate facilities, as well as pervasive mold, leading to health issues. Early Native American housing assistance programs through HUD had many issues, such as restricted assistance to low- and moderate-income borrowers, meaning those programs could not help those who needed it most. Community housing needs were not met, and sustainable housing was not built or maintained. The Native American Housing Assistance and Self-Determination Act of 1996 (NAHASDA) expanded housing programs to create community-based homeownership opportunities. These include: the Indian Home Loan Guarantee Program and the Tribal Housing Activities Loan Guarantee Program. These programs are a step in the right direction. However, as data shows, they are not effective enough to close the homeownership gap between Native American and non-Hispanic White populations.

Income

Based on the 2015-2019 ACS for American Indian and Alaska Native population, the median income of American Indian and Alaska Native households was $43,825 – slightly higher than the median income of African American households, which was $41,935. The Hispanic household income for that same period was $51,811. Altogether, these numbers are substantively lower than White, non-Hispanic household median income of $68,785. In 2015, the average income on reservations was 68% below the US average, about $17,000.

Poverty Rates

Based on the data from the 2018 US Census cited by Poverty USA, Native Americans have the highest poverty rate among all minority groups. The national poverty rate for Native Americans was 25.4%, while Black or African American poverty rate was 20.8%. Among Hispanics, the national poverty rate was 17.6%. The White population had an 8.1% national poverty rate during the same period.

Updated US Census Bureau data on poverty for 2019 and 2020 does not show Native Americans or Alaska Natives as a specific category, highlighting the continuous lack of information on this part of the US population. We do not know the full extent of their situation, but based on previous data, Native Americans have the highest rate of poverty in the nation.

Unemployment

According to the 2019 Bureau of Labor Statistics data, the unemployment rate for Native Americans was 6.1%. The unemployment rate for African Americans was also 6.1% while Hispanics had a 4.3% unemployment rate and Whites had a rate of 3.3%. In terms of employment, American Indians (including Alaska Natives) had a 57.1% employment-to-population ratio while African Americans had an employment-to-population ratio of 58.7%. White Americans had an employment-to-population ratio of 61% and Hispanics had the highest ratio at 63.9%. In both unemployment and employment, American Indians and African Americans are the most economically marginalized groups.

Educational Achievement

Despite increases in educational attainment over the last 25 years, Native Americans have the lowest educational achievement rates in comparison to other national racial and ethnic groups. According to the 2005-2019 ACS Briefs, 15% of Native Americans have a bachelor’s degree or higher. For comparison, 16.4% of Hispanics, 21.6% of African Americans and 33.5% of Whites have a bachelor’s degree or higher.

COVID-19 Pandemic/Health Disparities

Disparities in money, power and resources lead to disparities in Native American health. It is well established that housing stability is one of the most salient predictors of health outcomes. Homeownership is one of the central ways to build wealth, another important predictor. As a population, Native Americans do not have equitable access to affordable, quality housing and are one of the least wealthy groups in the United States. Many also live in rural communities without access to nearby healthcare. According to the Indian Health Service, American Indians and Alaska Natives have a life expectancy that is 5.5 years less than the total US population’s expectancy. They die at higher rates than other Americans in many categories, including liver and respiratory disease, diabetes, unintentional injuries, and more. This disparity is on clear display in the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic. According to research done by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, AI/AN people had 3.5 times more confirmed COVID-19 cases than non-Hispanic White people did. As is often the case, we do not know the extent of the impact of COVID-19 on AI/AN populations due to inadequate data collection. A closer look at Montana specifically from the Center for Infectious Disease Research and Policy at the University of Minnesota showed that 267 out of 100,000 Native Americans in Montana would die of COVID-19, compared to 73 out of 100,000 White people.

Dedrick Asante-Muhammad is the Chief of Membership, Policy and Equity at NCRC.

Esha Kamra is a former NCRC Membership, Policy, and Equity intern.

Connor Sanchez is an NCRC Membership, Policy and Equity Intern

Thanks to Kathy Ramirez and Rogelio Tec for their prior research.

[1] Asante Muhammad, Dedrick. Challenges to Native Americans Advancements: The Recession and Native Americans. District of Columbia: Institute for Policy Studies, 2009. Print.