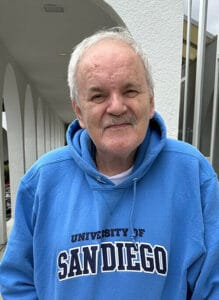

I don’t remember the first time I got a call from Dave Oddo, but it couldn’t have been very long after I came to NCRC in 2015. He talked to me about the work he had been doing using HMDA data in San Diego County since the late seventies – work he’d produced on typewriters using longhand math that I now do with software and high-powered computers.

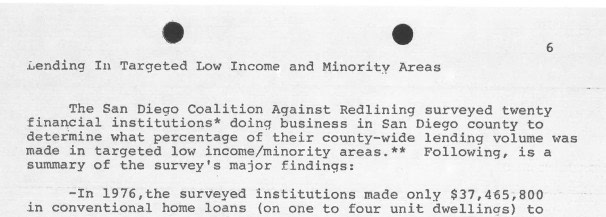

Dave’s relentless pursuit of fairness in mortgage lending began with a revelation—a newspaper headline in 1977 that unveiled the stark reality of redlining in San Diego County. Forming the San Diego Coalition Against Redlining, his mission was clear: to expose and eradicate the insidious practice that sidelined entire communities based on race and income.

I’m telling you this story because it should never have been this hard for everyday people like Dave to unearth the ugly realities of racism in their communities. And because now, it doesn’t have to be. But the people who did the hard yards to expose the rot in American economic development should be recognized.

By the time I picked up that phone in 2015, he’d been doing this work longer than I had – since before the personal computer, before coherent federal data gathering on mortgage lending, hell even before the VCR. Over the next few years, I would talk with Dave periodically. He was a key player when we asked the CFPB to continue producing reports on mortgage lending at the local level, making it easy for people to see how well lenders were servicing the communities. We lost that fight, but I was able to provide Dave with data for a few more reports.

Dave’s commitment to social justice and economic equality is extensive. Starting as a supporter of economic justice and labor rights for migrant and seasonal farmworkers in 1968, he has been involved in numerous campaigns and organizations dedicated to defending the rights of the poor and marginalized. He volunteered for the late Alan Cranston’s campaigns for US Senate, supported various boycotts for workers’ rights, and was actively involved in the United Farm Workers’ movements alongside Cesar Chavez.

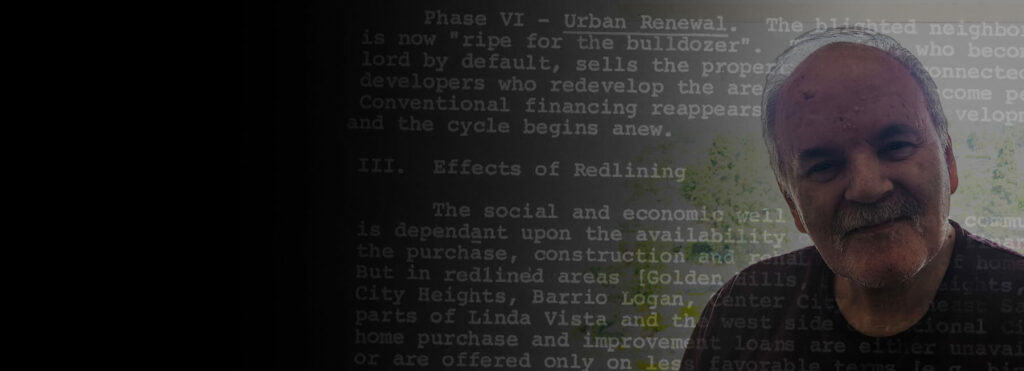

Areas plagued by redlining are typically integrated or predominantly minority. As minorities are more likely to reside in inner-city neighborhoods with older, smaller, wood-frame houses and are less likely to own their homes, the denial of loans to creditworthy minority applicants perpetuates past discrimination. Redlining keeps minorities segregated in the oldest, most run-down sections of town.

– “Redlining – Geographic Loan Discrimination in San Diego,” 1978, David Oddo & the San Diego Coalition Against Redlining

As a VISTA volunteer at the Legal Aid Society of San Diego, Dave organized and chaired the San Diego Coalition Against Redlining, co-authoring significant reports on geographic mortgage lending discrimination. His reports from the late 70s are akin to the discovery of the HOLC maps themselves, providing a crucial window into the persistent issues of redlining and lending discrimination.

Reading Dave’s reports, it is clear that even 40 years ago, it was understood that lenders were redlining minority communities, using mechanisms like appraisal bias, steering and structurally racist underwriting conditions to ensure loans were difficult, if not impossible, to obtain in redlined neighborhoods. What was amazing is that he was doing all of this using little more than the rudimentary tools available at the time. Mortgage data was reported on massive paper spreadsheets and required Dave to go through them line by line, calculate the differences between neighborhoods, and write about it using a typewriter.

Today, Dave’s efforts provide key context to NCRC’s new report on mortgage lending and redlining since 1981. This report makes use of a groundbreaking new tool Dave would have immediately understood, called the HMDA Longitudinal Database (HLD). For the first time there is a dataset that brings together 40 years of HMDA data in a way that researchers can use to look at the entire country. A generation of exclusion is documented clearly, and offers a powerful tool that lets everybody do what Dave did so laboriously in San Diego for so long. Dave’s examination of early HMDA data confirms that redlining was already firmly entrenched in San Diego, perpetuating the concentration of poverty and Black and Hispanic families in areas where, as Dave put it in one report, “Perceiving some ‘risk’, lenders decide that a neighborhood is on the decline and that ‘safer’ investments can be made by lending in outlying areas and suburbs[.]”

Lenders of the time were not shy about announcing the reasons for this assessment. A trade organization for the Savings and Loan industry, the United States League of Savings Associations, noted:

“The tightening of mortgage credit in older city neighborhoods follows, rather than leads, the decline in both the quality of life and property values. Deteriorating schools, inadequate police protection, poor street lighting, inadequate garbage collection, racial tension, and the gradual disappearance of first-class commercial stores and shops—all of these things precede lender nervousness with respect to any given neighborhood.”

Statements like those above highlight how lenders abdicated their responsibility to meet the credit needs of the entire community, not just the parts they liked. It is no wonder local bankers thought of Dave as an ‘agitator’ – His reports led to efforts by the Savings and Loan industry to cut funding for the Legal Aid Society of San Diego, where he volunteered and led the San Diego Coalition Against Redlining.

Over the following 40 years, Dave released report after report noting the exclusion of Black and Hispanic San Diegans from homeownership. Key findings from his reports read like those from our reports today:

- Significant Disparities in Lending: Minority neighborhoods received significantly fewer loans and investments than neighborhoods with higher white populations.

- Racial Divide in Homeownership: The racial divide in homeownership rates within San Diego County was significant, with minority communities facing substantial barriers to accessing mortgage loans.

- Persistent Loan Approval Gap: Reports showed a persistent gap in loan approval rates, with Black/African American and Hispanic/Latino applicants disproportionately denied home loans even with similar income levels.

- Call for Systemic Changes: The findings highlight a need for systemic changes in the banking industry to ensure fair practices for all communities. Oddo’s reports include a call to action for banks to undertake fair lending training and develop targeted programs to better serve minority populations.

Oddo’s work was a precursor to the national story we’ve unveiled through our new dataset. He traced the contours of systemic exclusion that our study now confirms on a grand scale. It isn’t by chance that our reports on redlining come to a lot of the same conclusions.

Dave told me that he is no longer writing HMDA reports. I’d say he’s earned some rest – and I know thousands upon thousands of people in the NCRC network are carrying that same work forward for him every day.

The narrative that Dave began sketching out in his reports on San Diego is just a small part of a national tapestry. Neighborhoods in every city, town, and county were marked for exclusion and erasure. What he identified locally was not an outlier; it was a microcosm of a nationwide crisis.

Now, with powerful new tools like the HMDA Longitudinal Database, you can do what Dave did by hand for so long.

Take a look at your community today and see where home loans have been going – and where they haven’t.

Then go be an agitator: Ask your local banks, lenders and community leaders why those patterns exist and what solutions can they offer to end those patterns of segregation.

Jason Richardson is NCRC’s Senior Director of Research.

Photos courtesy of Dave Oddo.

Really interesting and amazing that Dave did all this years ago! Nice article and tribute to D Abe’s hard work.