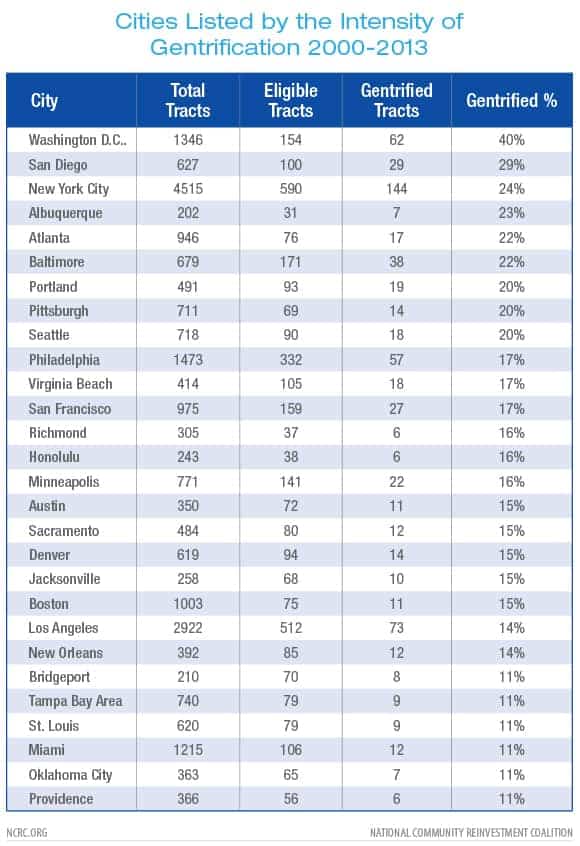

Gentrification and displacement of long-time residents is most intense in the nation’s biggest cities, and rare in most other places, a new study shows.

The study, from the National Community Reinvestment Coalition (NCRC), identified more than 1,000 neighborhoods in 935 cities and towns where gentrification occurred between 2000 and 2013. In 230 of those neighborhoods, rapidly rising rents, property values and taxes forced more than 135,000 residents to move away.

The study, using U.S. Census Bureau and economic data, lends weight to what critics say is a concentration not only of wealth, but of wealth-building investment, in just a handful of the nation’s biggest metropolises, while other regions of the country languish. It highlights how gentrification and cultural displacement have unfolded in American cities, while many low-income small towns and rural neighborhoods remain starved of investment.

Seven cities accounted for nearly half of the gentrification nationally: New York City, Los Angeles, Washington, D.C., Philadelphia, Baltimore, San Diego and Chicago.

Shifting neighborhoods: Gentrification and cultural displacement in American cities

- Overview

- Read the full report

- Local view: Philadelphia

- Local view: Portland, Oregon

- Local view: Richmond, Virginia

- Local view: Washington, D.C.

- Download the full report (PDF)

[optin-monster-shortcode id=”pp9hbd0oskt3h64b5asb”]

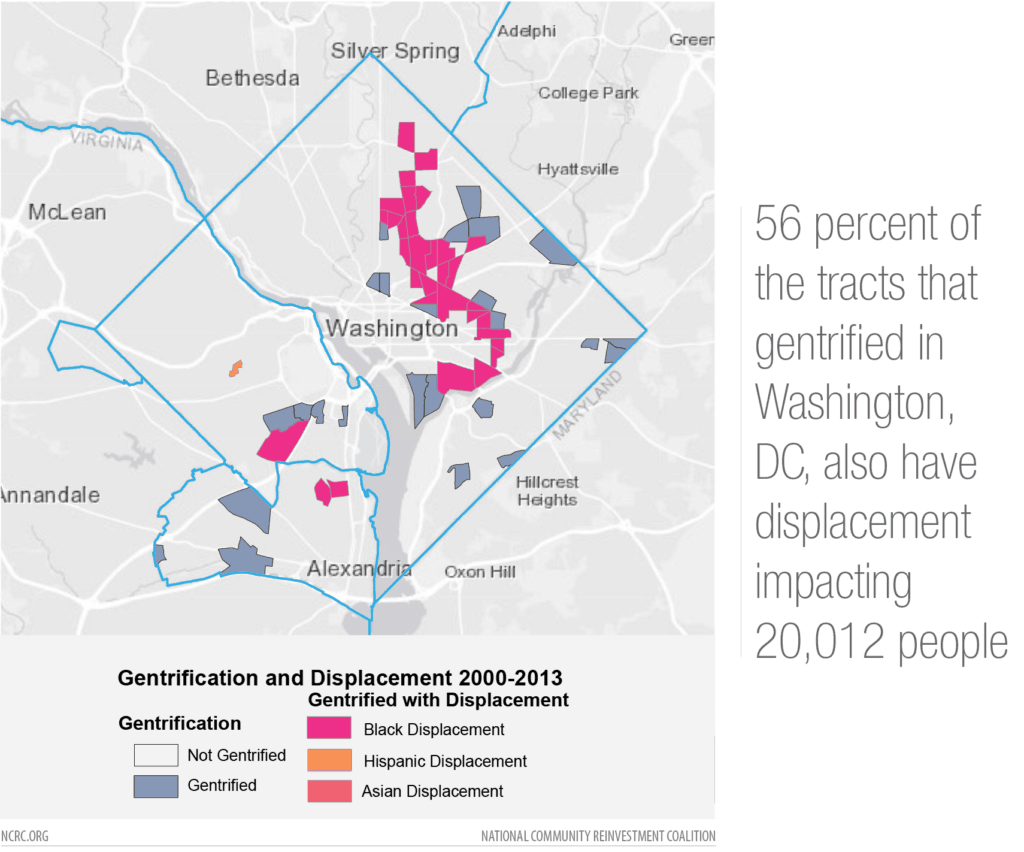

Washington, D.C., had the highest percentage of gentrifying neighborhoods. Nearly half the neighborhoods in the city were eligible for gentrification in 2000, and 41 percent of those neighborhoods gentrified by 2013, displacing more than 20,000 people. The continuation of a robust real estate market since 2013 means it is likely that this trend is continuing to this day.

“We’ve shown, with census and other data, that the influx of new, wealthier people into once struggling neighborhoods also drove out more than 135,000 people from a handful of booming cities,” said Jason Richardson, NCRC’s Director of Research and one of the study’s authors. “We’ve also shown that revitalization of struggling neighborhoods is unevenly distributed. The big investments that fuel gentrification and cultural displacement didn’t reach most of the nation’s poorest neighborhoods and rural areas.”

Gentrification is a term used to describe what happens when lower-income neighborhoods receive massive levels of new investment, adding amenities, raising home values and bringing in new upper-income residents. This can lead to cultural displacement, when members of a racial or ethnic group who were longtime residents of gentrified neighborhoods are pushed out.

For example, in the historic Shaw neighborhood of Washington, D.C., a traditionally black community, property prices skyrocketed over the last two decades, resulting in the cultural displacement of the congregation of the Lincoln Temple United Church of Christ, a staging ground for the 1963 Civil Rights March on Washington. When incoming residents did not join the congregation, its membership collapsed. By 2018, the regular congregation had shrunk to just 20 families, resulting in the closure of the historic community anchor.

This scenario played out in many black and Hispanic neighborhoods in America’s largest cities. While investment in low- and moderate-income communities remained weak across most of the 935 cities studied

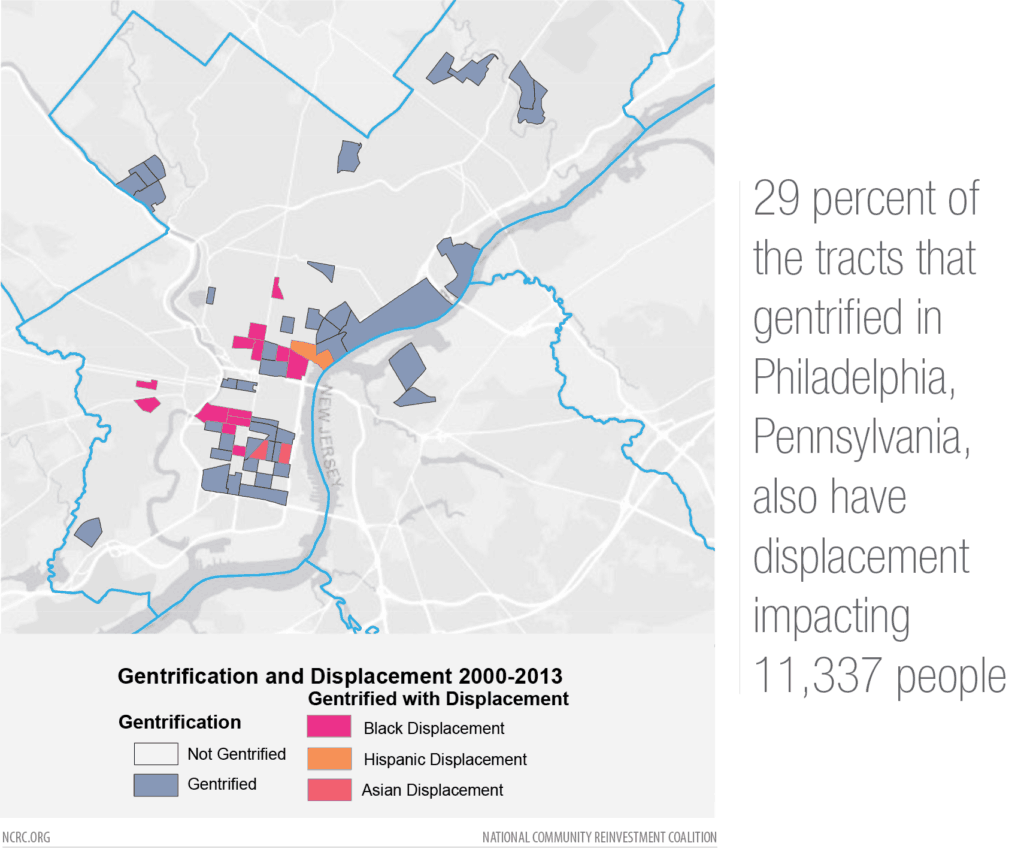

, gentrification occurred in many of the largest cities where economic activity and growth was greatest. In the largest cities, New York City, Los Angeles and Chicago, gentrification and displacement were spread out in different neighborhood clusters. In smaller cities, like Washington, D.C., Philadelphia and Baltimore, gentrification was concentrated near downtown business districts, spreading to adjacent neighborhoods, waterfronts and commercial areas where jobs and amenities are concentrated.

Often, these gentrifying areas had been abandoned by “white flight” as cities suburbanized after World War II and minority residents built communities of their own. Banks often refused to lend money in those neighborhoods, so most residents were renters. In most of the cities that NCRC reviewed, this was still the case; lending to home buyers and business owners in low-income minority areas was weaker than in higher-income neighborhoods. While gentrification usually happened in bigger cities, it could be just as disruptive in smaller cities. In the neighborhoods where gentrification took hold, rents skyrocketed as gentrifiers moved in.

There were also high rates of gentrification in Philadelphia, where more than 12,000 residents were impacted by cultural displacement centered around the core business district. The large number of neighborhoods that gentrified, and the number of displaced residents, rank Philadelphia among the worst cities for black displacement.

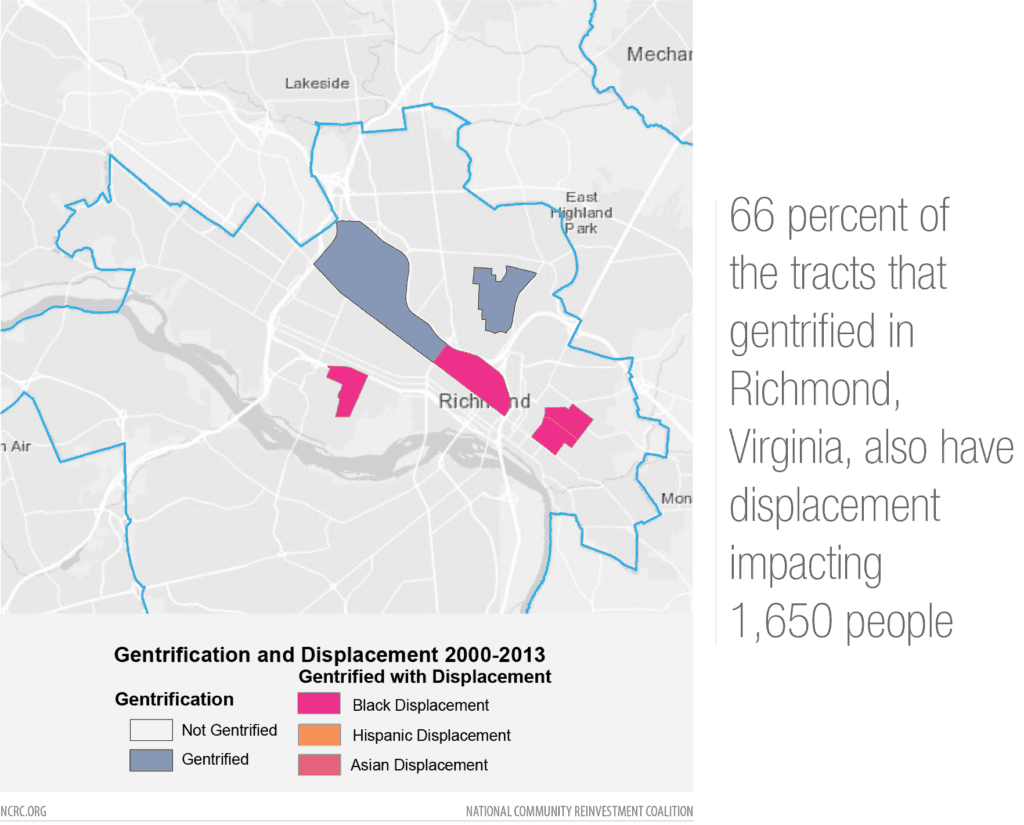

Cultural displacement doesn’t just impact big cities. In Richmond, Virginia, four of the six neighborhoods that gentrified showed indications of black cultural displacement. Up to half of the black residents living in these communities in 2000 were gone by 2013. Over 2,600 people missed out on the benefits of Richmond’s revitalization to make way for 1,900 white and Asian newcomers.

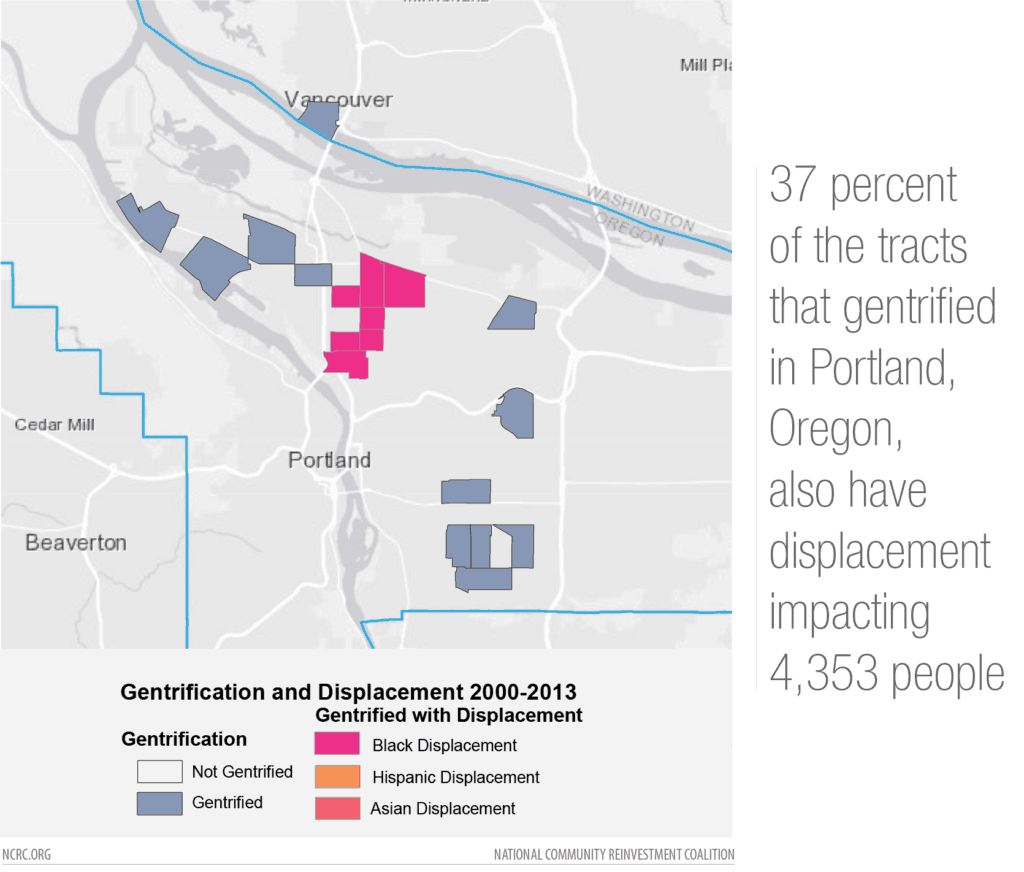

In Portland, Oregon, the gentrifying neighborhoods that held majority black populations were decimated by cultural displacement. On average, the nine neighborhoods of the central city lost more than 600 residents apiece, with more than 4,300 people pushed out just as Portland became the poster child of successful urbanism.

The study indicates that gentrification and cultural displacement often go hand in hand, excluding existing residents from the benefits of a revitalizing neighborhood. This doesn’t have to be how it works. Local communities can allow for revitalization and an influx of new residents, while preserving affordable housing options for the people who have called these neighborhoods home for decades.

“Policies like the Low Income Housing Tax Credit (LIHTC) and promotion of affordable housing goals should help diminish the cultural displacement that accompanies gentrification,” Richardson said. “But strong national policies and local action is also essential. NCRC works with local coalitions to help them encourage lending and investments that maintain affordable housing and commercial options for existing residents and businesses. Inclusive zoning rules, tax and rent controls, opportunity zones, split rate taxes and other policies are not exclusive of investment. They create the circumstances for inclusive neighborhood revitalization that preserve the vitality and character of neighborhoods.”

Photo by Jami via Wikicommons.

This is a very well-done and interesting study. If you are interested in a Kennedy School Working Paper that I, Victoria Alsina and another Kennedy School colleague prepared comparing gentrification and diversity issues relating to the reconstruction of the 14th Street corridor in Washington, D.C. following the ’68 riots and the redevelopment of Southwest DC in the 50s as part of urban renewal, go to

https://www.hks.harvard.edu/centers/mrcbg/publications/awp/awp74